Il Canto degli Italiani

| English: The Song of the Italians | |

|---|---|

|

Original text | |

|

National anthem of | |

| Also known as |

Inno di Mameli English: Mameli's Hymn Fratelli d'Italia English: Brothers of Italy |

| Lyrics | Goffredo Mameli, 1847 |

| Music | Michele Novaro, 1847 |

| Adopted |

October 12, 1946 (de facto) November 23, 2012 (de jure) |

|

| |

| Music sample | |

| Inno di Mameli (instrumental) | |

"Il Canto degli Italiani" ([il ˈkanto deʎʎ itaˈljaːni],[1] "The Song of the Italians") is the national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as "Inno di Mameli" ([ˈinno di maˈmɛːli], "Mameli's Hymn"), after the author of the lyrics, or "Fratelli d'Italia" ([fraˈtɛlli diˈtaːlja], "Brothers of Italy"), from its opening line. The words were written in the autumn of 1847 in Genoa, by the then 20-year-old student and patriot Goffredo Mameli. Two months later, they were set to music in Turin by another Genoese, Michele Novaro.[2] The hymn enjoyed widespread popularity throughout the period of the Risorgimento and in the following decades. Nevertheless, after the Italian Unification in 1861, the adopted national anthem was the "Marcia Reale" (Royal March), the official hymn of the House of Savoy composed in 1831 by order of Carlo Alberto di Savoia. After the Second World War, Italy became a republic, and on 12 October 1946, "Il Canto degli Italiani" was provisionally chosen as the country's new national anthem. This choice was made official in law only on 23 November 2012.[3]

History

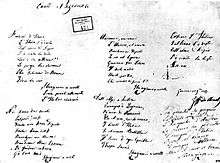

The first manuscript of the poem, preserved at the Istituto Mazziniano in Genoa, appears in a personal copybook of the poet, where he collected notes, thoughts and other writings. Of uncertain dating, the manuscript reveals anxiety and inspiration at the same time. The poet begins with È sorta dal feretro (It's risen from the bier) then seems to change his mind: leaves some room, begins a new paragraph and writes "Evviva l'Italia, l'Italia s'è desta" ("Hurray Italy, Italy has awakened"). The handwriting appears nervy and frenetic, with numerous spelling errors, among which are "Ilia" for "Italia" and "Ballilla" for "Balilla". The second manuscript is the copy that Goffredo Mameli sent to Michele Novaro for setting to music. It shows a much steadier handwriting, fixes misspellings, and has a significant modification: the incipit is "Fratelli d'Italia". This copy is in the Museo del Risorgimento in Turin. The hymn was also printed on leaflets in Genoa, by the printing office Casamara. The Istituto Mazziniano has a copy of these, with hand annotations by Mameli himself. This sheet, subsequent to the two manuscripts, lacks the last strophe ("Son giunchi che piegano...") for fear of censorship. These leaflets were to be distributed on the December 10 demonstration, in Genoa.[4]

December 10, 1847 was an historical day for Italy: the demonstration was officially dedicated to the 101st anniversary of the popular rebellion which led to the expulsion of the Austrian powers from the city; in fact it was an excuse to protest against foreign occupations in Italy and induce Carlo Alberto to embrace the Italian cause of liberty. In this occasion the tricolor flag was shown and Mameli's hymn was publicly sung for the first time. After December 10 the hymn spread all over the Italian peninsula, brought by the same patriots that participated in the Genoa demonstration. In the 1848, Mameli's hymn was very popular among the Italian people and it was commonly sung during demonstrations, protests and revolts as a symbol of the Italian Unification in most parts of Italy. In the Five Days of Milan, the rebels sang the Song of the Italians during clashes against the Austrian Empire.[5] In the 1860, the corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi used to sing the hymn in the battles against the Bourbons in Sicily and Southern Italy.[6] Giuseppe Verdi, in his "Inno delle nazioni" (Hymn of the nations), composed for the London International Exhibition of 1862, chose "Il Canto degli Italiani" to represent Italy, putting it beside "God Save the Queen" and "La Marseillaise". On 20 September 1870, in the last part of the Italian Risorgimento, the Capture of Rome was characterised by the people who sang the Mameli's hymn played by the Bersaglieri marching band although the Kingdom of Italy had adopted the "Marcia Reale" as national anthem in 1861.[7]

During the period of Italian Fascism, the "Song of the Italians" continued to play an important role as patriotic hymn along with several popular fascist songs. After the armistice of Cassibile, Mameli's hymn was curiously sung by both the Italian partisans and the people who supported the Italian Social Republic.[8]

After the Second World War, following the birth of the Italian Republic, the "Song of the Italians" was de facto adopted as national anthem. On 23 November 2012, this choice was made official in law.[9]

Lyrics

This is the complete text of the original poem written by Goffredo Mameli. However, the Italian anthem, as commonly performed in official occasions, is composed of the first stanza sung twice, and the chorus, then ends with a loud "Sì!" ("Yes!").

The first stanza presents the personification of Italy who is ready to go to war to become free, and shall be victorious as Rome was in ancient times, "wearing" the helmet of Scipio Africanus who defeated Hannibal at the final battle of the Second Punic War at Zama; there is also a reference to the ancient Roman custom of slaves who used to cut their hair short as a sign of servitude, hence the Goddess of Victory must cut her hair in order to be slave of Rome (to make Italy victorious).[10] In the second stanza the author complains that Italy has been a divided nation for a long time, and calls for unity; in this stanza Goffredo Mameli uses three words taken from the Italian poetic and archaic language: calpesti (modern Italian, calpestati), speme (modern Italian, speranza), raccolgaci (modern Italian, ci raccolga).

The third stanza is an invocation to God to protect the loving union of the Italians struggling to unify their nation once and for all. The fourth stanza recalls popular heroic figures and moments of the Italian fight for independence such as the battle of Legnano, the defence of Florence led by Ferruccio during the Italian Wars, the riot started in Genoa by Balilla, and the Sicilian Vespers. The last stanza of the poem refers to the part played by Habsburg Austria and Czarist Russia in the partitions of Poland, linking its quest for independence to the Italian one.[11]

Fratelli d'Italia, |

Brothers of Italy,

|

CORO |

CHORUS

|

Noi fummo da secoli[N 1]

|

We were for centuries |

CORO |

CHORUS |

Uniamoci, amiamoci, |

Let us unite, let us love one another, |

CORO |

CHORUS |

Dall'Alpi a Sicilia |

|

CORO |

CHORUS |

Son giunchi che piegano |

Mercenary swords, |

CORO |

CHORUS |

Additional verses

The last strophe was deleted by the author, to the point of being barely readable. It was dedicated to Italian women:

Tessete o fanciulle |

Weave o maidens |

Notes

References

- ↑ (Italian) DOP entry .

- ↑ "Italy - Il Canto degli Italiani/Fratelli d'Italia". NationalAnthems.me. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ↑ "LEGGE 23 novembre 2012 , n. 222 - Norme sull'acquisizione di conoscenze e competenze in materia di "Cittadinanza e Costituzione" e sull'insegnamento dell'inno di Mameli nelle scuole. (12G0243)". Gazzette.comune.jesi.an.it. 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "Inno di Mameli - Il canto degli Italiani: testo, analisi e storia". labandadeisei.it. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "IL CANTO DEGLI ITALIANI: il significato". Radiomarconi.com. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "Il canto degli italiani - 150 anni di". Progettocentocin.altervista.org. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "La breccia di Porta Pia". 150anni-lanostrastoria.it. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "I canti di Salò". Archiviostorico.info. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "Inno Di Mameli, Insegnamento Obbligatorio Nelle Scuole Italiane. La Camera Pprova Il Ddl | Clandestinoweb | Sondaggio | Media | Politica". Clandestinoweb. 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "Il testo dell'Inno di Mameli. Materiali didattici di Scuola d'Italiano Roma a cura di Roberto Tartaglione" (in Italian). Scudit.net. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ "L'Inno nazionale". Quirinale.it. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

External links

| Italian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Page on the official site of the Quirinale, residence of the Head of State

(in Italian with several recorded performances – click on ascolta l'Inno and choose a file to listen) - Free sheet music of Il Canto degli Italiani from Cantorion.org

- Streaming audio, lyrics and information about the Italian national anthem

- Listen to the Italian national anthem

- Fratelli d'Italia: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (Version for chorus and piano by Claudio Dall'Albero on a musical proposal of Luciano Berio)

|