Isometry

In mathematics, an isometry is a distance-preserving injective map between metric spaces.

Introduction

Given a metric space (loosely, a set and a scheme for assigning distances between elements of the set), an isometry is a transformation which maps elements to the same or another metric space such that the distance between the image elements in the new metric space is equal to the distance between the elements in the original metric space. In a two-dimensional or three-dimensional Euclidean space, two geometric figures are congruent if they are related by an isometry: related by either a rigid motion (translation or rotation), or a composition of a rigid motion and a reflection. They are equal, up to an action of a rigid motion, if related by a direct isometry (orientation preserving).

Isometries are often used in constructions where one space is embedded in another space. For instance, the completion of a metric space M involves an isometry from M into M', a quotient set of the space of Cauchy sequences on M. The original space M is thus isometrically isomorphic to a subspace of a complete metric space, and it is usually identified with this subspace. Other embedding constructions show that every metric space is isometrically isomorphic to a closed subset of some normed vector space and that every complete metric space is isometrically isomorphic to a closed subset of some Banach space.

An isometric surjective linear operator on a Hilbert space is called a unitary operator.

Formal definitions

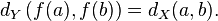

Let X and Y be metric spaces with metrics dX and dY. A map ƒ : X → Y is called an isometry or distance preserving if for any a,b ∈ X one has

An isometry is automatically injective. (Otherwise two distinct points, a and b, could be mapped to the same point, which would contradict the coincidence axiom of the metric d.) This proof is similar to the proof that an order embedding between partially ordered sets is injective. Clearly, every isometry between metric spaces is a topological embedding (i.e. a homeomorphism).

A global isometry, isometric isomorphism or congruence mapping is a bijective isometry.

Two metric spaces X and Y are called isometric if there is a bijective isometry from X to Y. The set of bijective isometries from a metric space to itself forms a group with respect to function composition, called the isometry group.

There is also the weaker notion of path isometry or arcwise isometry:

A path isometry or arcwise isometry is a map which preserves the lengths of curves; such a map is not necessarily an isometry in the distance preserving sense, and it need not necessarily be bijective, or even injective. This term is often abridged to simply isometry, so one should take care to determine from context which type is intended.

Examples

- Any reflection, translation and rotation is a global isometry on Euclidean spaces. See also Euclidean group.

- The map

in

in  is a path isometry but not an isometry. Note that unlike an isometry, it is not injective.

is a path isometry but not an isometry. Note that unlike an isometry, it is not injective.

- The isometric linear maps from Cn to itself are the unitary matrices.

Linear isometry

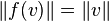

Given two normed vector spaces V and W, a linear isometry is a linear map f : V → W that preserves the norms:

for all v in V. Linear isometries are distance-preserving maps in the above sense. They are global isometries if and only if they are surjective.

By the Mazur-Ulam theorem, any surjective isometry of normed vector spaces over R is affine.

In an inner product space, the fact that any linear isometry is an orthogonal transformation can be shown by using polarization to prove <Ax, Ay> = <x, y> and then applying the Riesz representation theorem.

Generalizations

- Given a positive real number ε, an ε-isometry or almost isometry (also called a Hausdorff approximation) is a map

between metric spaces such that

between metric spaces such that

- for x,x′ ∈ X one has |dY(ƒ(x),ƒ(x′))−dX(x,x′)| < ε, and

- for any point y ∈ Y there exists a point x ∈ X with dY(y,ƒ(x)) < ε

- That is, an ε-isometry preserves distances to within ε and leaves no element of the codomain further than ε away from the image of an element of the domain. Note that ε-isometries are not assumed to be continuous.

- The restricted isometry property characterizes nearly isometric matrices for sparse vectors.

- Quasi-isometry is yet another useful generalization.

- One may also define an element in an abstract unital C*-algebra to be an isometry:

is an isometry if and only if

is an isometry if and only if  .

.

- Note that as mentioned in the introduction this is not necessarily a unitary element because one does not in general have that left inverse is a right inverse.

- On a pseudo-Euclidean space, the term isometry means a linear bijection preserving magnitude. See also Quadratic spaces.

See also

- Motion (geometry)

- Isometric projection

- Euclidean plane isometry

- 3D isometries that leave the origin fixed

- Space group

- Involution

- Isometries in physics

- Homeomorphism group

- Partial isometry

References

Further reading

- F. S. Beckman and D. A. Quarles, Jr., On isometries of Euclidean space, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc., 4 (1953) 810-815.