Isosceles triangle

| Isosceles triangle | |

|---|---|

|

Isosceles triangle with vertical axis of symmetry | |

| Type | triangle |

| Edges and vertices | 3 |

| Schläfli symbol | ( ) ∨ { } |

| Symmetry group | Dih2, [ ], (*), order 2 |

| Dual polygon | Self-dual |

| Properties | convex, cyclic |

In geometry, an isosceles triangle is a triangle that has two sides of equal length. Sometimes it is specified as having two and only two sides of equal length, and sometimes as having at least two sides of equal length, the latter version thus including the equilateral triangle as a special case.

By the isosceles triangle theorem, the two angles opposite the equal sides are themselves equal, while if the third side is different then the third angle is different.

By the Steiner–Lehmus theorem, every triangle with two angle bisectors of equal length is isosceles.

Terminology

In an isosceles triangle that has exactly two equal sides, the equal sides are called legs and the third side is called the base. The angle included by the legs is called the vertex angle and the angles that have the base as one of their sides are called the base angles.[1]

Euclid defined an isosceles triangle as one having exactly two equal sides,[2] but modern treatments prefer to define them as having at least two equal sides, making equilateral triangles (with three equal sides) a special case of isosceles triangles.[3] In the equilateral triangle case, since all sides are equal, any side can be called the base, if needed, and the term leg is not generally used.

Symmetry

A triangle with exactly two equal sides has exactly one axis of symmetry, which goes through the vertex angle and also goes through the midpoint of the base. Thus the axis of symmetry coincides with (1) the angle bisector of the vertex angle, (2) the median drawn to the base, (3) the altitude drawn from the vertex angle, and (4) the perpendicular bisector of the base.[4]

Acute, right and obtuse

Whether the isosceles triangle is acute, right or obtuse depends on the vertex angle. In Euclidean geometry, the base angles cannot be obtuse (greater than 90°) or right (equal to 90°) because their measures would sum to at least 180°, the total of all angles in any Euclidean triangle. Since a triangle is obtuse (resp. right) if and only if one of its angles is obtuse (resp. right), an isosceles triangle is obtuse, right or acute if and only if its vertex angle is respectively obtuse, right or acute.

Euler line

The Euler line of any triangle goes through the triangle's orthocenter (the intersection of its three altitudes), its centroid (the intersection of its three medians), and its circumcenter (the intersection of its three sides' perpendicular bisectors, which is the center of the circumcircle that passes through the three vertices). In an isosceles triangle with exactly two equal sides, the Euler line coincides with the axis of symmetry. This can be seen as follows. Since as pointed out in the previous section the axis of symmetry coincides with an altitude, the intersection of the altitudes, which must lie on that altitude, must therefore lie on the axis of symmetry; since the axis coincides with a median, the intersection of the medians, which must lie on that median, must therefore lie on the axis of symmetry; and since the axis coincides with a perpendicular bisector, the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors, which must lie on that perpendicular bisector, must therefore lie on the axis of symmetry.

If the vertex angle is acute (so the isosceles triangle is an acute triangle), then the orthocenter, the centroid, and the circumcenter all fall inside the triangle. If the vertex angle, and therefore the triangle, is obtuse, then the centroid still falls in the triangle's interior, but the circumcenter falls outside it (beyond the base).

In an isosceles triangle the incenter (the intersection of its angle bisectors, which is the center of the incircle, that is, the circle which is internally tangent to the triangle's three sides) lies on the Euler line.

Steiner inellipse

The Steiner inellipse of any triangle is the unique ellipse that is internally tangent to the triangle's three sides at their midpoints. In an isosceles triangle, if the legs are longer than the base then the Steiner inellipse's major axis coincides with the triangle's axis of symmetry; if the legs are shorter than the base, then the ellipse's minor axis coincides with the triangle's axis of symmetry.

Formulas

For an isosceles triangle with equal sides of length a and base of length b, the general triangle formulas for (1) the length of the triangle-interior portion of the angle bisector of the vertex angle, (2) the length of the median drawn to the base, (3) length of the altitude drawn to the base, and (4) the length of the triangle-interior portion of the perpendicular bisector of the base all simplify to

For any isosceles triangle with area T and perimeter p, we have[5]:Eq.(1)

Area

Heron's formula for the area T of a triangle simplifies in the case of an isosceles triangle to

This can be derived using the Pythagorean Theorem. The sum of the squares of half the base b and the height h is the square of either of the other two sides of length a.

By substituting the height, the formula for the area of an isosceles triangle can be derived:

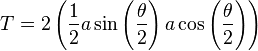

If the vertex angle (θ) and leg lengths (a) of an isosceles triangle are known, then the area of that triangle is:

This is derived by drawing a perpendicular line from the base of the triangle, which bisects the vertex angle and creates two right triangles. The bases of these two right triangles are both equal to the hypotenuse times the sine of the bisected angle by definition of the term "sine". For the same reason, the heights of these triangles are equal to the hypotenuse times the cosine of the bisected angle. Using the trigonometric identity sin(θ) = 2sin(θ/2)cos(θ/2), we get:

The isosceles triangle theorem

The theorem which states that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal appears as Proposition I.5 in Euclid.[6] This result has been called the pons asinorum (the bridge of asses). Some say that this is probably because of the diagram used by Euclid in his demonstration of the result. Others claim that the name stems from the fact that this is the first difficult result in Euclid, and acts to separate those who can understand Euclid's geometry from those who can't.[7]

Partitioning into isosceles triangles

For any integer n ≥ 4, any triangle can be partitioned into n isosceles triangles.[8]

In a right triangle, the median from the hypotenuse (that is, the line segment from the midpoint of the hypotenuse to the right-angled vertex) divides the right triangle into two isosceles triangles. This is because the midpoint of the hypotenuse is the center of the circumcircle of the right triangle, and each of the two triangles created by the partition has two equal radii as two of its sides.[9]:p.24

The golden triangle is isosceles and has a ratio of either leg to the base equal to the golden ratio, and has angles 72°, 72°, and 36° in the ratios 2:2:1. It can be partitioned into another golden triangle and a golden gnomon, also isosceles, with ratio of base to leg equaling the golden ratio and with angles 36°, 36°, and 108° in the ratios 1:1:3.[9]:p.30-31

Miscellaneous

If a cubic equation has two complex roots and one real root, then when these roots are plotted in the complex plane they are the vertices of an isosceles triangle whose axis of symmetry coincides with the horizontal (real) axis. This is because the complex roots are complex conjugates and hence are symmetric about the real axis.

Either diagonal of a rhombus divides it into two congruent isosceles triangles.

The Calabi triangle, which is isosceles, is the unique non-equilateral triangle in which the largest square that fits in its interior can be positioned in any of three different ways.

If an isosceles triangle ABC with equal legs AB and BC has a segment drawn from A to a point D on ray BC, and if the reflection of AD around AC intersects ray BC at E, then BC2 = BD × BE.[10]

There are exactly two distinct isosceles triangles with given area T and perimeter p if the isoperimetric inequality holds strictly as  If the inequality is replaced by the corresponding equality, there is only one such triangle, which is equilateral.[5]:Thm.2

If the inequality is replaced by the corresponding equality, there is only one such triangle, which is equilateral.[5]:Thm.2

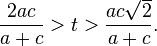

If the two equal sides have length a and the other side has length c, then the internal angle bisector t from one of the two equal-angled vertices satisfies[11]:p.169,# 44

44

Fallacy of the isosceles triangle

A well known fallacy is the proof (?) of the statement that all triangles are isosceles. This argument has been attributed to Lewis Carroll,[12] but W.W. Rouse Ball claims priority in this matter.[13] The fallacy is rooted in Euclid's lack of recognition of the concept of betweenness and the resulting ambiguity of inside versus outside of figures.

See also

- Equilateral triangle

- Golden triangle, an isosceles triangle with sides in the golden ratio

- Isosceles right triangle

- Dragon's Eye (symbol)

Notes

- ↑ Jacobs 1974, p. 144

- ↑ Heath 1956, p. 187, Definition 20

- ↑ Stahl 2003, p. 37

- ↑ Ostermann & Wanner 2012, p. 55, Exercise 7

- 1 2 George Baloglou and Michel Helfgott. "Angles, area, and perimeter caught in a cubic", Forum Geometricorum 8, 2008, 13-25. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2008volume8/FG200803.pdf

- ↑ Heath 1956, p. 251

- ↑ Venema 2006, p. 89

- ↑ Lord, N. J. (June 1982), "Isosceles subdivisions of triangles", Mathematical Gazette 66: 136–137, doi:10.2307/3617750

- 1 2 Posamentier, Alfred S., and Lehmann, Ingmar. The Secrets of Triangles. Prometheus Books, 2012.

- ↑ Dutta, Surajit. "A simple property of isosceles triangles with applications", Forum Geometricorum 14, 2014, 237-240. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2014volume14/FG201422index.html

- ↑ Inequalities proposed in “Crux Mathematicorum”, .

- ↑ Robin Wilson (2008). Lewis Carroll in Numberland. Penguin Books. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-14-101610-8.

- ↑ Ball, W.W. Rouse; Coxeter, H.S.M. (1987) [1892], Mathematical Recreations and Essays (13th ed.), Dover, p. 77 footnote, ISBN 0-486-25357-0

References

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956), The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements 1 (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.), New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60088-2

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1974), Geometry, W. H. Freeman and Co., ISBN 0-7167-0456-0

- Ostermann, Alexander; Wanner, Gerhard (2012), Geometry by Its History, Springer, ISBN 978-3-642-29162-3

- Stahl, Saul (2003), Geometry from Euclid to Knots, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-032927-4

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006), Foundations of Geometry, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-143700-3

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Isosceles triangle", MathWorld.