Avalon

| Avalon | |

|---|---|

The Last Sleep of Arthur by Edward Burne-Jones | |

| Historia Regum Britanniae location | |

| Creator | Geoffrey of Monmouth |

| Genre | Arthurian legend |

| Type | Legendary island of the dead |

| Notable characters | King Arthur, Morgan le Fay |

Avalon (/ˈævəˌlɒn/; Welsh: Ynys Afallon; probably from afal, meaning "apple") is a legendary island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 pseudohistorical account Historia Regum Britanniae ("The History of the Kings of Britain") as the place where King Arthur's sword Excalibur was forged and later where Arthur was taken to recover from his wounds after the Battle of Camlann. Avalon was associated from an early date with mystical practices and people such as Morgan le Fay.

Etymology

Geoffrey of Monmouth referred to it in Latin as Insula Avallonis in the Historia. In the later Vita Merlini he called it Insula Pomorum the "isle of fruit trees" (from Latin pōmus "fruit tree"). The name is generally considered to be of Welsh origin (though an Old Cornish or Old Breton origin is also possible), derived from Old Welsh aball, "apple/fruit tree" (in later Middle Welsh spelled avall; now Modern Welsh afall).[1][2][3][4] In Breton, apple is spelled "aval"/ "avaloù" in plural. It is also possible that the tradition of an "apple" island among the British was influenced by Irish legends concerning the otherworld island home of Manannán mac Lir and Lugh, Emain Ablach (also the Old Irish poetic name for the Isle of Man),[1] where Ablach means "Having Apple Trees"[5] – derived from Old Irish aball ("apple")—and is similar to the Middle Welsh name Afallach, which was used to replace the name Avalon in medieval Welsh translations of French and Latin Arthurian tales. All are etymologically related to the Gaulish root *aballo- (as found in the place name Aballo/Aballone, now Avallon in Burgundy or in the Italian surname Avallone) and are derived from a Common Celtic *abal- "apple", which is related at the Proto-Indo-European level to English apple, Russian яблоко (jabloko), Latvian ābele, et al.[6][7]

In Arthurian legend

.jpg)

According to Geoffrey in the Historia and much subsequent literature which he inspired, Avalon is the place where King Arthur is taken after fighting Mordred at the Battle of Camlann to recover from his wounds. Welsh, Cornish and Breton tradition claimed that Arthur had never really died, but would inexorably return to lead his people against their enemies. The Historia also states that Avalon is where his sword Excalibur was forged. Geoffrey dealt with Avalon in more detail in Vita Merlini, in which he describes for the first time in Arthurian legend the enchantress Morgan le Fay as the chief of nine sisters (Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Tyronoe, Thiten and Thiton)[8] who live on Avalon. Geoffrey's description of the island indicates a sea voyage was needed to get there. His description of Avalon here, which is heavily indebted to the early medieval Spanish scholar Isidore of Seville (being mostly derived from the section on famous islands in Isidore's famous work Etymologiae, XIV.6.8 "Fortunatae Insulae"), shows the magical nature of the island:

- The island of apples which men call “The Fortunate Isle” (Insula Pomorum quae Fortunata uocatur) gets its name from the fact that it produces all things of itself; the fields there have no need of the ploughs of the farmers and all cultivation is lacking except what nature provides. Of its own accord it produces grain and grapes, and apple trees grow in its woods from the close-clipped grass. The ground of its own accord produces everything instead of merely grass, and people live there a hundred years or more. There nine sisters rule by a pleasing set of laws those who come to them from our country.[9]

By comparison, Isidore's description of the Fortunate Isles reads:

- "The name of the Isles of the Fortunate signifies that they bear all good things, as if happy and blessed in the abundance of their fruits. Serviceable by nature, they bring forth fruits of valuable forests (Sua enim aptae natura pretiosarum poma silvarum parturiunt); their hilltops are clothed with vines growing by chance; in place of grasses, there is commonly vegetable and grain. Pagan error and the songs of the secular poets have held that these islands to be Paradise because of the fecundity of the soil. Situated in the Ocean to the left of Mauretania, very near the west, they are separated by the sea flowing between them."[10]

In medieval geographies, Isidore's Fortunate Islands were identified with the Canaries.[11]

Connection to Glastonbury

Around 1190, Avalon became associated with Glastonbury, when monks at Glastonbury Abbey claimed to have discovered the bones of Arthur and his queen. The works of Gerald of Wales make the first known connection:

- What is now known as Glastonbury was, in ancient times, called the Isle of Avalon. It is virtually an island, for it is completely surrounded by marshlands. In Welsh it is called Ynys Afallach, which means the Island of Apples and this fruit once grew in great abundance. After the Battle of Camlann, a noblewoman called Morgan, later the ruler and patroness of these parts as well as being a close blood-relation of King Arthur, carried him off to the island, now known as Glastonbury, so that his wounds could be cared for. Years ago the district had also been called Ynys Gutrin in Welsh, that is the Island of Glass, and from these words the invading Saxons later coined the place-name 'Glastingebury'.[12]

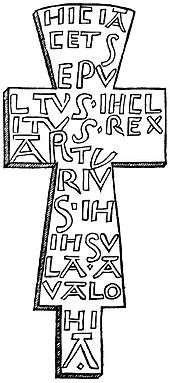

Though no longer an island in the twelfth century, the high conical bulk of Glastonbury Tor had been surrounded by marsh before the surrounding fenland in the Somerset Levels was drained. In ancient times, Ponter's Ball Dyke would have guarded the only entrance to the island. The Romans eventually built another road to the island.[13] Gerald wrote that Glastonbury's earliest name in Welsh was Ineswitrin (or Ynys Witrin), the Isle of glass, a name noted by earlier historians which suggests that the location was at one point seen as an island. The discovery of the burial is described by chroniclers, notably Gerald of Wales, as being just after King Henry II's reign when the new abbot of Glastonbury, Henry de Sully, commissioned a search of the abbey grounds. At a depth of 5 m (16 feet) the monks were said to have discovered a massive treetrunk coffin and a leaden cross bearing the inscription:

- Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arturius in insula Avalonia.

- ("Here lies entombed the renowned King Arthur in the island of Avalon").

Accounts of the exact inscription vary, with five different versions existing. The earliest is by Gerald in "Liber de Principis instructione" c. 1193, who wrote that he viewed the cross in person and traced the lettering. His transcript reads: "Here lies buried the famous King Arthur ("Arthurus") with Guinevere ("Wenneveria") his second wife in the isle of Avalon". Inside the coffin were two bodies, who Giraldus refers to as Arthur and "his queen"; the bones of the male body were described as being gigantic. The account of the burial by the chronicle of Margam Abbey says three bodies were found, the other being of Mordred.[14] In 1278, the remains were reburied with great ceremony, attended by King Edward I and his queen, before the High Altar at Glastonbury Abbey, where they were the focus of pilgrimages until the Reformation.

The story is today seen as an example of pseudoarchaeology. Historians today generally dismiss the authenticity of the find, attributing it to a publicity stunt performed to raise funds to repair the Abbey, which was mostly burned in 1184.[15] Long before this William of Malmesbury, a historian interested in Arthur, said in his history of England "But Arthur’s grave is nowhere seen, whence antiquity of fables still claims that he will return."[16] As William wrote a comprehensive history of Glastonbury De antiquitae Glatoniensis ecclesie around 1130 which discussed many pious legends connected to the Abbey, but made no mention of either Arthur's grave or a connection of Glastonbury to the name Avalon, stating firmly it was previously known as Ineswitrin, this raises further suspicions concerning the burial. It is known for certain the monks later added forged passages to William's history discussing Arthurian connections.[17] The fact that the search for the body is connected to Henry II and Edward I, both kings who fought major Welsh wars, has had scholars suggest that propaganda may have played a part as well.[18] Gerald, a constant supporter of royal authority, in his account of the discovery clearly aims to destroy the idea of the possibility of King's Arthur's messianic return: "Many tales are told and many legends have been invented about King Arthur and his mysterious ending. In their stupidity the British [i.e. Welsh, Cornish and Bretons] people maintain that he is still alive. Now that the truth is known, I have taken the trouble to add a few more details in this present chapter. The fairy-tales have been snuffed out, and the true and indubitable facts are made known, so that what really happened must be made crystal clear to all and separated from the myths which have accumulated on the subject."[19]

The burial discovery ensured that in later romances, histories based on them and in the popular imagination Glastonbury became increasingly identified with Avalon, an identification that continues strongly today. The later development of the legends of the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea by Robert de Boron interconnected these legends with Glastonbury and with Avalon, an identification which also seems to be made in Perlesvaus. The popularity of Arthurian Romance has meant this area of the Somerset Levels has today become popularly described as The Vale Of Avalon.[20] In more recent times writers such as Dion Fortune, John Michell, Nicholas Mann and Geoffrey Ashe have formed theories based on perceived connections between Glastonbury and Celtic legends of the otherworld and Annwn in attempts to link the location firmly with Avalon, drawing on the various legends based on Glastonbury Tor as well as drawing on ideas like Earth mysteries, Ley lines and even the myth of Atlantis. Arthurian literature also continues to use Glastonbury as an important location as in The Mists of Avalon, A Glastonbury Romance and The Bones of Avalon. Even the fact that Somerset has many apple orchards has been drawn in to support the connection. Glastonbury's connection to Avalon continues to make it a site of tourism and the area has great religious significance for Neopagans, Neo-druids and as a New Age community, as well as Christians. Hippy identification of Glastonbury with Avalon seen in the work of Michell and in Gandalf's Garden also helped inspire the Glastonbury Festival.[21]

Other locations for Avalon

In medieval times suggestions for the location of Avalon ranged far beyond Glastonbury. They included on the other side of the Earth at the antipodes, Sicily and other unnamed locations in the Mediterranean.[22] In more recent times, just like in the quest for Arthur's mythical capital Camelot, a large number of locations have been put forward as being the real "Avalon".

Geoffrey Ashe suggests an association of Avalon with the town of Avallon in Burgundy, as part of a theory connecting King Arthur to the Romano-British leader Riothamus who campaigned in that area.[23]

Non-Arthurian notability

Places named after Avalon

A number of places around the world are named after Avalon.

- Avalon, California is the main town on Santa Catalina Island off Southern California.

- Avalon, New Jersey is a small beachside town.

- Avalon Airport is a small, currently used airport just outside Melbourne, Australia.

- Avalon Beach, New South Wales is a beachside suburb in Sydney, Australia.

- Avalon, New Zealand is a suburb of Lower Hutt, in the Wellington metropolitan area.

- During the 17th century, the area surrounding one of North America's first European settlements Ferryland, was named after the legendary isle.

- Originally called the Province of Avalon, in modern times the Avalon Peninsula in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador contains that province's capital.

Avalon in culture

Avalon is a major setting for many modern works of fiction or fantasy, including non-Arthurian French literature, folklore, and epic poems as well as in later works without other connections to King Arthur. Several examples are listed below.

Avalon in non-Arthurian French literature, folklore, and epic poems

Examples include:

- Li coronemenz Looïs (an anonymous twelfth-century Old French chanson de geste, in which appears the phrase por tot l'or d'Avalon "for all the gold of Avalon")[24]

- The legends of Holger Danske, who was taken there by the sorceress Morgan le Fay of Arthurian legend

- The legends of Melusine. It also recurs in a number of later works without other connections to King Arthur

Avalon in modern fiction

Avalon is a major setting for many modern works of fiction or fantasy. Several examples are listed below.

In comics

- Marvel Comics has two different Avalons.

- Avalon also appears in the The New 52 DC Comics book series, Demon Knights.

In literature

- Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon, ISBN 0345350499

- The Chronicles of Amber (1970-1991) by Roger Zelazny is a fantasy book series that references Avalon as shadow-kingdom formerly ruled by Corwin, the protagonist of the first five novels.

- In Chapter 19 of James Rollins' sixth Sigma Force novel, The Doomsday Key (2009), Father Rye and historian Wallace Boyd tell the group seeking the Doomsday Key that Bardsey Island was home to Fomorian royalty and that Merlin was a famous Druid priest, buried on sacred Bardsey Island with other prominent Druids. In the book's "Fact or Fiction" epilogue, Rollins writes: "Bardsey Island truly is Avalon. All the stories and mythologies of the island are accurate, including Merlin's tomb, Lord Newborough's Crypt, and the twenty thousand buried saints. Also, the Bardsey apple continues to grow, and cuttings can be purchased of this ancient tree. As to those nasty currents around the island, those are also real."[25]

- In Poul Anderson's Technic History, Avalon is the name of a planet with a colony composed jointly of Humans and the eagle-like Ythrian aliens.

In video games

- In the online game Wizard101, there is a playable world called Avalon.

- In the game Tomb Raider: Legend, Amelia get through the ring to Avalon.

- In the game Ace Combat Zero: The Belkan War, Avalon is the name of a hydroelectric dam and missile silo.

In television

- Avalon has been referenced in the science-fiction television series Stargate SG-1 (see Avalon (Stargate SG-1)).

- Avalon and many other Arthurian legends are referenced in the anime "Fate/stay Night"

- Avalon and many other Arthurian legends are referenced in Game Soul Sacrifice and Soul Sacrifice Delta

- Avalon is the setting of the mid-1990s animated series Princess Gwenevere and the Jewel Riders.

- Avalon is also visited by the protagonists during the Disney/Buena Vista animated series Gargoyles, and is both the starting point and the core location of the nineteen-episode "Avalon World Tour" story arc of the series.

- Avalon (Avila) is the city in Spain that Cary Grant (British Officer), Frank Sinatra (Spaniard Revolutionary), and Sophia Loren (Love Interest and Revolutionary); must move a gigantic canon to fight the French.

- Avalon is featured in Once Upon a Time. Guinevere once received special sand from Rumplestiltskin that came from Avalon as part of a deal to complete Excalibur.

In music

Led Zeppelin sings "I'm waiting for the angels of Avalon, waiting for the eastern glow." in the song "The Battle of Evermore", along with references to the Latin meaning of Avalon (apple): "The apples of the valley hold the seeds of happiness".

"Avalon" is a song from the album "Avalon", the eighth and final studio album released in May 1982, by Roxy Music.

The line "Sweet Avalon, the heat is on" is found in the track "A Call to Arms" from Mike & The Mechanics' first album.

Avalon Sunset is the nineteenth studio album by Northern Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison, released in 1989. Morrison also wrote the song "Avalon of the Heart", which was included on his next album Enlightenment in 1990.

"Avalon" is a song from the album Fables & Dreams by Swiss symphonic metal band Lunatica.

"Avalon" is a song on acoustic oriented band Fiction Family's 2013 album Fiction Family Reunion.[26]

"Back to Avalon" is a song on the album Desire Walks On by rock group Heart (band).

"Avalon" is the title of a song on the album Axis Mundi (2015) by Brown Bird.

"Avalon" is a song on the album Empire of the Undead by power metal group Gamma Ray.

"Sail Away to Avalon" is a song on the first Ayreon album, The Final Experiment.

See also

References

- Citations

- 1 2 Koch, John. Celtic Culture:a historical encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO 2006, p. 146.

- ↑ Savage, John J. H. "Insula Avallonia", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 73, (1942), pp. 405–415.

- ↑ Nitze, William Albert, Jenkins, Thomas Atkinson. Le Haut Livre du Graal, Phaeton Press, 1972, p. 55.

- ↑ Zimmer, Heinrich. Bretonische Elemente in der Artursage des Gottfried von Monmouth, Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, Volume 12, 1890, pp. 246–248.

- ↑ Marstrander, Carl Johan Sverdrup (ed.), Dictionary of the Irish Language, Royal Irish Academy, 1976, letter A, column 11, line 026.

- ↑ Hamp, Eric P. The north European word for ‘apple’, Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, 37, 1979, pp. 158–166.

- ↑ Adams, Douglas Q. The Indo-European Word for 'apple' Again. Indogermanische Forschungen, 90, 1985, pp. 79–82.

- ↑ Berthelot, Anne, “Apprivoiser la merveille”, in: Mélanges en l’honneur de Francis Dubost, Paris: Champion, 2005, pp. 49–66.

- ↑ The Vita Merlini

- ↑ Priscilla Throop, "Isidore of Seville's Etymologies", Lulu.com, 2005, XIV.6.8

- ↑ Priscilla Throop, "Isidore of Seville's Etymologies", Lulu.com, 2005, XIV.6.8, n. 50

- ↑ Gerald of Wales, "Liber de Principis instructione" c.1193 Two Accounts of the Exhumation of Arthur's Body

- ↑ Allcroft, Arthur Hadrian (1908), Earthwork of England: Prehistoric, Roman, Saxon, Danish, Norman and Mediæval, Nabu Press, pp. 69–70, ISBN 978-1-178-13643-2, retrieved 12 April 2011

- ↑ Carley, James P. (2001), Glastonbury Abbey and the Arthurian tradition, D.S. Brewer, p. 316, ISBN 978-0-85991-572-4

- ↑ Modern scholarship views the Glastonbury cross as the result of a probably late 12th-century fraud. See Rahtz 1993 and Carey 1999.

- ↑ O. J. Padel, "The Nature of Arthur" in Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 27 (1994), pp. 1–31 at p.10

- ↑ Glastonbury in Norris J. Lacy, Editor, The Arthurian Encyclopedia (1986 Peter Bedrick Books, New York).

- ↑ Rahtz 1993

- ↑ Gerald of Wales – Two Accounts of the Exhumation of Arthur's Body

- ↑ The Guardian – Treadmill in the Vale of Avalon 1990

- ↑ "Glastonbury: Alternative Histories", in Ronald Hutton, Witches, Druids and King Arthur

- ↑ Avalon in Norris J. Lacy, Editor, The Arthurian Encyclopedia (1986 Peter Bedrick Books, New York).

- ↑ Geoffrey Ashe (1985), The Discovery of King Arthur, London: Guild Publishing, pp. 95–96,

(p95) In Welsh it is Ynys Avallach. Geoffrey's Latin equivalent is Insula Avallonis. It has been influenced by the spelling of a real place called Avallon. Avallon is a Gaulish name with the same meaning, and the real Avalon is in Burgundy—where Arthur's Gallic career ends. Again, we glimpse an earlier and different passing of Arthur, on the Continent and not in Britain. (p. 96) Riothamus too led an army of Britons into Gaul, and was the only British King who did. He too advanced to the neighbourhood of Burgundy. He too was betrayed by a deputy ruler who treated with barbarian enemies. He, too, is last located in Gaul among the pro-Roman Burgundians. He, too, disappears after a fatal battle, without any recorded death. The line of his retreat, prolonged on a map, shows that he was going in the direction of the real Avalon. (p. 96)

- ↑ Chambers, Edmund Kerchever. Arthur of Britain, Speculum Historiale, 1964, p. 219.

- ↑ Rollins, James (2009). The Doomsday Key. pp. Chapter 19 and Fact or Fiction.

- ↑ "Avalon Lyrics". Metrolyrics. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Bibliography

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Avalon. |

- Rahtz, Philip (1993), English Heritage Book of Glastonbury, London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-6865-6.

- Carey, John (1999), "The Finding of Arthur’s Grave: A Story from Clonmacnoise?", in Carey, John; Koch, John T.; Lambert, Pierre-Yves, Ildánach Ildírech. A Festschrift for Proinsias Mac Cana, Andover: Celtic Studies Publications, pp. 1–14, ISBN 978-1-891271-01-4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||