Islanding

Islanding refers to the condition in which a distributed generator (DG) continues to power a location even though electrical grid power from the electric utility is no longer present. Islanding can be dangerous to utility workers, who may not realize that a circuit is still powered, and it may prevent automatic re-connection of devices. For that reason, distributed generators must detect islanding and immediately stop producing power; this is referred to as anti-islanding.

The common example of islanding is a grid supply line that has solar panels attached to it. In the case of a blackout, the solar panels will continue to deliver power as long as irradiance is sufficient. In this case, the supply line becomes an "island" with power surrounded by a "sea" of unpowered lines. For this reason, solar inverters that are designed to supply power to the grid are generally required to have some sort of automatic anti-islanding circuitry in them.

In intentional islanding, the generator disconnects from the grid, and forces the distributed generator to power the local circuit. This is often used as a power backup system for buildings that normally sell their excess power to the grid.

Islanding basics

Electrical inverters are devices that convert direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC). Grid-interactive inverters have the additional requirement that they produce AC power that matches the existing power presented on the grid. In particular, a grid-interactive inverter must match the voltage, frequency and phase of the power line it connects to. There are numerous technical requirements to the accuracy of this tracking.

Consider the case of a house with an array of solar panels on the roof. Inverter(s) attached to the panels convert the varying DC current provided by the panels into AC power that matches the grid supply. If the grid is disconnected, the voltage on the grid line might be expected to drop to zero, a clear indication of a service interruption. However, consider the case when the house's load exactly matches the output of the panels at the instant of the grid interruption. In this case the panels can continue supplying power, which is used up by the house's load. In this case there is no obvious indication that an interruption has occurred.

Normally, even when the load and production are exactly matched, the so-called "balanced condition", the failure of the grid will result in several additional transient signals being generated. For instance, there will almost always be a brief decrease in line voltage, which will signal a potential fault condition. However, such events can also be caused by normal operation, like the starting of a large electric motor.

Methods that detect islanding without a large number of false positives is the subject of considerable research. Each method has some threshold that needs to be crossed before a condition is considered to be a signal of grid interruption, which leads to a "non-detection zone" (NDZ), the range of conditions where a real grid failure will be filtered out.[1]

Questionable rationale

Given the activity in the field, and the large variety of methods that have been developed to detect islanding, it is important to consider whether or not the problem actually demands the amount of effort being expended. Generally speaking, the reasons for anti-islanding are given as (in no particular order):[2][3]

- Safety concerns: if an island forms, repair crews may be faced with unexpected live wires

- End-user equipment damage: customer equipment could theoretically be damaged if operating parameters differ greatly from the norm. In this case, the utility is liable for the damage.

- Ending the failure: Reclosing the circuit onto an active island may cause problems with the utility's equipment, or cause automatic reclosing systems to fail to notice the problem.

- Inverter confusion: Reclosing onto an active island may cause confusion among the inverters.

The first issue has been widely dismissed by many in the power industry. Line workers are already constantly exposed to unexpectedly live wires in the course of normal events (i.e. is a house blacked out because it has no power, or because they pulled the main breaker inside?). Normal operating procedures under hot-line rules or dead-line rules require line workers to test for power as a matter of course, and it has been calculated that active islands would add a negligible risk.[4] However, other emergency workers may not have time to do a line check, and these issues have been extensively explored using risk-analysis tools. A UK-based study concluded that "The risk of electric shock associated with islanding of PV systems under worst-case PV penetration scenarios to both network operators and customers is typically <10−9 per year."[5]

The second possibility is also considered extremely remote. In addition to thresholds that are designed to operate quickly, islanding detection systems also have absolute thresholds that will trip long before conditions are reached that could cause end-user equipment damage. It is, generally, the last two issues that cause the most concern among utilities. Reclosers are commonly used to divide up the grid into smaller sections that will automatically, and quickly, re-energize the branch as soon as the fault condition (a tree branch on lines for instance) clears. There is some concern that the reclosers may not re-energize in the case of an island, or that the rapid cycling they cause might interfere with the ability of the DG system to match the grid again after the fault clears.

If an islanding issue does exist, it appears to be limited to certain types of generators. A 2004 Canadian report concluded that synchronous generators, installations like microhydro, were the main concern. These systems may have considerable mechanical inertia that will provide a useful signal. For inverter based systems, the report largely dismissed the problem; "Anti-islanding technology for inverter based DG systems is much better developed, and published risk assessments suggest that the current technology and standards provide adequate protection while penetration of DG into the distribution system remains relatively low."[6] The report also noted that "views on the importance of this issue tend to be very polarized," with utilities generally considering the possibility of occurrence and its impacts, while those supporting DG systems generally use a risk based approach and the very low probabilities of an island forming.[7]

An example of such an approach, one that strengthens the case that islanding is largely a non-issue, is a major real-world islanding experiment that was carried out in the Netherlands in 1999. Although based on then-current anti-islanding system, typically the most basic voltage jump detection methods, the testing clearly demonstrated that islands could not last longer than 60 seconds. Moreover, the theoretical predictions were true; the chance of a balance condition existing were on the order of 10−6 a year, and that the chance that the grid would disconnect at that point in time was even less. As an island can only form when both conditions are true, they concluded that the "Probability of encountering an islanding is virtually zero"[8]

Nevertheless, utility companies have continued to use islanding as a reason to delay or refuse the implementation of distributed generation systems. In Ontario, Ontario Hydro recently introduced interconnection guidelines that refused connection if the total distributed generation capacity on a branch was 7% of the maximum yearly peak power.[9] At the same time, California sets a limit of 15% only for review, allowing connections up to 30%,[10] and is actively considering moving the review-only limit to 50%.

The issue can be hotly political. In Ontario a number of potential customers taking advantage of a new Feed-in tariff program were refused connection only after building their systems. This was a problem particularly in rural areas where numerous farmers were able to set up small (10 kWp) systems under the "capacity exempt" microFIT program only to find that Hydro One had implemented a new capacity regulation after the fact, in many cases after the systems had been installed.[11]

Islanding detection methods

Detecting an islanding condition is the subject of considerable research. In general, these can be classified into passive methods, which look for transient events on the grid, and active methods, which probe the grid by sending signals of some sort from the inverter or the grid distribution point. There are also methods that the utility can use to detect the conditions that would cause the inverter-based methods to fail, and deliberately upset those conditions in order to make the inverters switch off. A Sandia Labs Report covers many of these methodologies, both in-use and future developments. These methods are summarized below.

Passive methods

Passive methods include any system that attempts to detect transient changes on the grid, and use that information as the basis as a probabilistic determination of whether or not the grid has failed, or some other condition has resulted in a temporary change.

Under/over voltage

According to Ohm's law, the voltage in an electrical circuit is a function of electric current (the supply of electrons) and the applied load (resistance). In the case of a grid interruption, the current being supplied by the local source is unlikely to match the load so perfectly as to be able to maintain a constant voltage. A system that periodically samples voltage and looks for sudden changes can be used to detect a fault condition.[12]

Under/over voltage detection is normally trivial to implement in grid-interactive inverters, because the basic function of the inverter is to match the grid conditions, including voltage. That means that all grid-interactive inverters, by necessity, have the circuitry needed to detect the changes. All that is needed is an algorithm to detect sudden changes. However, sudden changes in voltage are a common occurrence on the grid as loads are attached and removed, so a threshold must be used to avoid false disconnections.[13]

The range of conditions that result in non-detection with this method may be large, and these systems are generally used along with other detection systems.[14]

Under/over frequency

The frequency of the power being delivered to the grid is a function of the supply, one that the inverters carefully match. When the grid source is lost, the frequency of the power would fall to the natural resonant frequency of the circuits in the island. Looking for changes in this frequency, like voltage, is easy to implement using already required functionality, and for this reason almost all inverters also look for fault conditions using this method as well.

Unlike changes in voltage, it is generally considered highly unlikely that a random circuit would naturally have a natural frequency the same as the grid power. However, many devices deliberately synchronize to the grid frequency, like televisions. Motors, in particular, may be able to provide a signal that is within the NDZ for some time as they "wind down". The combination of voltage and frequency shifts still results in a NDZ that is not considered adequate by all.[15]

Rate of change of frequency

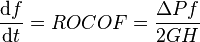

In order to decrease the time in which an island is detected, rate of change of frequency has been adopted as a detection method. The rate of change of frequency is given by the following expression:

where  is the system frequency,

is the system frequency,  is the time,

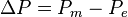

is the time,  is the power imbalance (

is the power imbalance ( ),

),  is the system capacity, and

is the system capacity, and  is the system inertia.

is the system inertia.

Should the rate of change of frequency, or ROCOF value, be greater than a certain value, the embedded generation will be disconnected from the network.

Voltage phase jump detection

Loads generally have power factors that are not perfect, meaning that they do not accept the voltage from the grid perfectly, but impede it slightly. Grid-tie inverters, by definition, have power factors of 1. This can lead to changes in phase when the grid fails, which can be used to detect islanding.

Inverters generally track the phase of the grid signal using a phase locked loop (PLL) of some sort. The PLL stays in sync with the grid signal by tracking when the signal crosses zero volts. Between those events, the system is essentially "drawing" a sine-shaped output, varying the current output to the circuit to produce the proper voltage waveform. When the grid disconnects, the power factor suddenly changes from the grid's (1) to the load's (~1). As the circuit is still providing a current that would produce a smooth voltage output given the known loads, this condition will result in a sudden change in voltage. By the time the waveform is completed and returns to zero, the signal will be out of phase.[15]

The main advantage to this approach is that the shift in phase will occur even if the load exactly matches the supply in terms of Ohm's law - the NDZ is based on power factors of the island, which are very rarely 1. The downside is that many common events, like motors starting, also cause phase jumps as new impedances are added to the circuit. This forces the system to use relatively large thresholds, reducing its effectiveness.[16]

Harmonics detection

Even with noisy sources, like motors, the total harmonic distortion (THD) of a grid-connected circuit is generally unmeasurable due to the essentially infinite capacity of the grid that filters these events out. Inverters, on the other hand, generally have much larger distortions, as much as 5% THD. This is a function of their construction; some THD is a natural side-effect of the switched-mode power supply circuits most inverters are based on.[17]

Thus, when the grid disconnects, the THD of the local circuit will naturally increase to that of the inverters themselves. This provides a very secure method of detecting islanding, because there are generally no other sources of THD that would match that of the inverter. Additionally, interactions within the inverters themselves, notably the transformers, have non-linear effects that produce unique 2nd and 3rd harmonics that are easily measurable.[17]

The drawback of this approach is that some loads may filter out the distortion, in the same way that the inverter attempts to. If this filtering effect is strong enough, it may reduce the THD below the threshold needed to trigger detection. Systems without a transformer on the "inside" of the disconnect point will make detection more difficult. However, the largest problem is that modern inverters attempt to lower the THD as much as possible, in some cases to unmeasurable limits.[17]

Active methods

Active methods generally attempt to detect a grid failure by injecting small signals into the line, and then detecting whether or not the signal changes.

Negative-sequence current injection

This method is an active islanding detection method which can be used by three-phase electronically coupled distributed generation (DG) units. The method is based on injecting a negative-sequence current through the voltage-sourced converter (VSC) controller and detecting and quantifying the corresponding negative-sequence voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC) of the VSC by means of a unified three-phase signal processor (UTSP). The UTSP system is an enhanced phase-locked loop (PLL) which provides high degree of immunity to noise, and thus enable islanding detection based on injecting a small negative-sequence current. The negative-sequence current is injected by a negative-sequence controller which is adopted as the complementary of the conventional VSC current controller. The negative-sequence current injection method: • detects an islanding event within 60 ms (3.5 cycles) under UL1741 test conditions; • requires 2% to 3% negative-sequence current injection for islanding detection; • can correctly detect an islanding event for the grid short circuit ratio of 2 or higher; • is insensitive to variations of the load parameters of UL1741 test system. For more details about this method, the reader is referred to: "Negative-Sequence Current Injection for Fast Islanding Detection of a Distributed Resource Unit", Houshang Karimi, Amirnaser Yazdani, and Reza Iravani, IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON POWER ELECTRONICS, VOL. 23, NO. 1, JANUARY 2008.

Impedance measurement

Impedance Measurement attempts to measure the overall impedance of the circuit being fed by the inverter. It does this by slightly "forcing" the current amplitude through the AC cycle, presenting too much current at a given time. Normally this would have no effect on the measured voltage, as the grid is an effectively infinitely stiff voltage source. In the event of a disconnection, even the small forcing would result in a noticeable change in voltage, allowing detection of the island.[18]

The main advantage of this method is that it has a vanishingly small NDZ for any given single inverter. However, the inverse is also the main weakness of this method; in the case of multiple inverters, each one would be forcing a slightly different signal into the line, hiding the effects on any one inverter. It is possible to address this problem by communication between the inverters to ensure they all force on the same schedule, but in a non-homogeneous install (multiple installations on a single branch) this becomes difficult or impossible in practice. Additionally, the method only works if the grid is effectively infinite, and in practice many real-world grid connections do not sufficiently meet this criterion.[18]

Impedance measurement at a specific frequency

Although the methodology is similar to Impedance Measurement, this method, also known as "harmonic amplitude jump", is actually closer to Harmonics Detection. In this case, the inverter deliberately introduces harmonics at a given frequency, and as in the case of Impedance Measurement, expects the signal from the grid to overwhelm it until the grid fails. Like Harmonics Detection, the signal may be filtered out by real-world circuits.[19]

Slip mode frequency shift

This is one of the newest methods of islanding detection, and in theory, one of the best. It is based on forcing the phase of the inverter's output to be slightly mis-aligned with the grid, with the expectation that the grid will overwhelm this signal. The system relies on the actions of a finely tuned phase-locked loop to become unstable when the grid signal is missing; in this case, the PLL attempts to adjust the signal back to itself, which is tuned to continue to drift. In the case of grid failure, the system will quickly drift away from the design frequency, eventually causing the inverter to shut down.[20]

The major advantage of this approach is that it can be implemented using circuitry that is already present in the inverter. The main disadvantage is that it requires the inverter to always be slightly out of time with the grid, a lowered power factor. Generally speaking, the system has a vanishingly small NDZ and will quickly disconnect, but it is known that there are some loads that will react to offset the detection.[20]

Frequency bias

Frequency bias forces a slightly off-frequency signal into the grid, but "fixes" this at the end of every cycle by jumping back into phase when the voltage passes zero. This creates a signal similar to Slip Mode, but the power factor remains closer to that of the grid's, and resets itself every cycle. Moreover, the signal is less likely to be filtered out by known loads. The main disadvantage is that every inverter would have to agree to shift the signal back to zero at the same point on the cycle, say as the voltage crosses back to zero, otherwise different inverters will force the signal in different directions and filter it out.[21]

There are numerous possible variations to this basic scheme. The Frequency Jump version, also known as the "zebra method", inserts forcing only on a specific number of cycles in a set pattern. This dramatically reduces the chance that external circuits may filter the signal out. This advantage disappears with multiple inverters, unless some way of synchronizing the patterns is used.[22]

Utility-based methods

The utility also has a variety of methods available to it to force systems offline in the event of a failure.

Manual disconnection

Most small generator connections require a mechanical disconnect switch, so at a minimum the utility could send a repairman to pull them all. For very large sources, one might simply install a dedicated telephone hotline that can be used to have an operator manually shut down the generator. In either case, the reaction time is likely to be on the order of minutes, or hours.

Automated disconnection

Manual disconnection could be automated through the use of signals sent though the grid, or on secondary means. For instance, power line carrier communications could be installed in all inverters, periodically checking for signals from the utility and disconnecting either on command, or if the signal disappears for a fixed time. Such a system would be highly reliable, but expensive to implement.[23][24]

Transfer-trip method

As the utility can be reasonably assured that they will always have a method for discovering a fault, whether that be automated or simply looking at the recloser, it is possible for the utility to use this information and transmit it down the line. This can be used to force the tripping of properly equipped DG systems by deliberately opening a series of recloser in the grid to force the DG system to be isolated in a way that forces it out of the NDZ. This method can be guaranteed to work, but requires the grid to be equipped with automated recloser systems, and external communications systems that guarantee the signal will make it through to the reclosers.[25]

Impedance insertion

A related concept is to deliberately force a section of the grid into a condition that will guarantee the DG systems will disconnect. This is similar to the transfer-trip method, but uses active systems at the head-end of the utility, as opposed to relying on the topology of the network.

A simple example is a large bank of capacitors that are added to a branch, left charged up and normally disconnected by a switch. In the event of a failure, the capacitors are switched into the branch by the utility after a short delay. This can be easily accomplished through automatic means at the point of distribution. The capacitors can only supply current for a brief period, ensuring that the start or end of the pulse they deliver will cause enough of a change to trip the inverters.[26]

There appears to be no NDZ for this method of anti-islanding. Its main disadvantage is cost; the capacitor bank has to be large enough to cause changes in voltage that will be detected, and this is a function of the amount of load on the branch. In theory, very large banks would be needed, an expense the utility is unlikely to look on favourably.[27]

SCADA

Anti-islanding protection can be improved through the use of the Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems already widely used in the utility market. For instance, an alarm could sound if the SCADA system detects voltage on a line where a failure is known to be in progress. This does not affect the anti-islanding systems, but may allow any of the systems noted above to be quickly implemented.

References

Notes

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 10

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 13

- ↑ CANMET, pg. 3

- ↑ CANMET, pg. 9-10

- ↑ "Risk analysis of islanding of photovoltaic power systems within low voltage distribution networks". CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .114 .2752 - ↑ CANMET, pg. 45

- ↑ CANMET, pg. 1

- ↑ Verhoeven, pg. 46

- ↑ "Technical Interconnection Requirements for Distributed Generation", Hydro One, 2010

- ↑ "California Electric Rule 21 Supplemental Review Guideline"

- ↑ Jonathan Sher, "Ontario Hydro pulls plug on solar plans", The London Free Press (via QMI), 14 February 2011

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 17

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 18

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 19

- 1 2 Bower & Ropp, pg. 20

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 21

- 1 2 3 Bower & Ropp, pg. 22

- 1 2 Bower & Ropp, pg. 24

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 26

- 1 2 Bower & Ropp, pg. 28

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 29

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 34

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 40

- ↑ CANMET, pg. 13-14

- ↑ CANMET, pg. 12-13

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 37

- ↑ Bower & Ropp, pg. 38

Bibliography

- Ward Bower and Michael Ropp, "Evaluation of Islanding Detection Methods for Utility-Interactive Inverters in Photovoltaic Systems", Sandia National Laboratories, November 2002

- CANMET (2004). "An Assessment of Distributed Generation Islanding Detection Methods and Issues for Canada". CANMET Energy Center. CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .131 .6506 - Bas Verhoeven, "Probability of Islanding in Utility Network due to Grid Connected Photovoltaic Power Systems", KEMA, 1999

- H. Karimi, A. Yazdani, and R. Iravani, Negative-Sequence Current Injection for Fast Islanding Detection of a

Distributed Resource Unit, IEEE Trans. on Power Electronics, VOL. 23, NO. 1, JANUARY 2008.

Standards

- IEEE 1547 Standards, IEEE Standard for Interconnecting Distributed Resources with Electric Power Systems

- UL 1741 Table of Contents, UL 1741: Standard for Inverters, Converters, Controllers and Interconnection System Equipment for Use With Distributed Energy Resources