Muslim conquest of Persia

| ||||||

The Muslim conquest of Persia, also known as the Arab conquest of Iran,[2] led to the end of the Sasanian Empire in 651 and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Iran.

The rise of Muslims coincided with a significant political, social, economic and military weakness in Persia. Once a major world power, the Sassanian Empire had exhausted its human and material resources after decades of warfare against the Byzantine Empire. The internal political situation had deteriorated, with the King Khosrau II being executed and ten new claimants taking the throne within just four years. The last one, Yazdegerd III, who had to face the Muslim invasion, was eight years old.

Arab Muslims first attacked the Sassanid territory in 633, when general Khalid ibn Walid invaded Mesopotamia (Sassanid province of Asōristān; what is now Iraq), which was the political and economic center of the Sassanid state.[3] Following the transfer of Khalid to the Byzantine front in the Levant, the Muslims eventually lost their holdings to Sassanian counterattacks. The second invasion began in 636 under Saad ibn Abi Waqqas, when a key victory at the Battle of Qadisiyyah led to the permanent end of Sasanian control west of Iran. The Zagros mountains then became a natural barrier and border between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sassanid Empire. Due to continuous raids by Persians into the area, Caliph Umar ordered a full invasion of the Sasanian empire in 642, which led to the complete conquest of the Sasanians around 651.a[›] Directing from Medina, more than a thousand miles from the battlefields of Iran, Caliph Umar's quick conquest of Iran in a series of well coordinated, multi-pronged attacks became his greatest triumph, contributing to his reputation as a great military and political strategist.[4]

Iranian historians have sought to defend their forebears by using Arab sources to illustrate that "contrary to the claims of some historians, Iranians, in fact, fought long and hard against the invading Arabs."[5] By 651, most of the urban centers in Iranian lands, with the notable exception of the Caspian provinces (Tabaristan) and Transoxiana, had come under the domination of the Arab armies. Many localities in Iran staged a defense against the invaders, but in the end none was able to repulse the invasion. Even after the Arabs had subdued the country, many cities rose in rebellion, killing the Arab governor or attacking their garrisons, but reinforcements from the caliphs succeeded in putting down all these rebellions and imposing the rule of Islam. The violent subjugation of Bukhara after many uprisings is a case in point. Conversion to Islam was, however, only gradual. In the process, many acts of violence took place, Zoroastrian scriptures were burnt and many priests executed.[6] Once conquered politically, the Persians began to reassert themselves by maintaining Persian language and culture. Regardless, Islam was adopted by many, for political, socio-cultural or spiritual reasons, or simply by persuasion, and became the dominant religion.[7][8]

Historiography and recent scholarship

When Western academics first investigated the Muslim conquest of Persia, they only had to rely on the accounts of the Armenian Christian bishop Sebeos, and accounts in Arabic that were written some time after the events they describe. The most significant work was probably that of Arthur Christensen, and his L’Iran sous les Sassanides, published in Copenhagen and Paris in 1944.[9]

However recent scholarship, both Iranian and Western, has begun to question the traditional narrative. Parvaneh Pourshariati, in her Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, published in 2008, provides both a detailed overview of the problematic nature of trying to establish exactly what happened, and a great deal of original research that questions fundamental facts of the traditional narrative, including the timeline and specific dates.

Pourshariati's central thesis is that contrary to what was commonly assumed, the Sassanian Empire was highly decentralized, and was in fact a "confederation" with the Parthians, who themselves retained a high level of independence.[10] Despite their recent victories over the Byzantine Empire, the Parthians unexpectedly withdrew from the confederation, and the Sassanians were thus ill-prepared and ill-equipped to mount an effective and cohesive defense against the Muslim armies.[11] Moreover, the powerful northern and eastern Parthian families, the kust-i khwarasan and kust-i adurbadagan, withdrew to their respective strongholds and made peace with the Arabs, refusing to fight alongside the Sassanians.

Another important theme of Pourshariati's study is a re-evaluation of the traditional timeline. Pourshariati argues that the Arab conquest of Mesopotamia "took place, not, as has been conventionally believed, in the years 632–634, after the accession of the last Sasanian king Yazdgerd III (632–651) to power, but in the period from 628 to 632."[12] An important consequence of this change in timeline means that the Arab conquest started precisely when the Sassanians and Parthians were engaged in internecine warfare over succession to the Sassanian throne.[12]

Sassanid Empire before the Conquest

Since the 1st century BC, the border between the Roman (later Byzantine) and Parthian (later Sassanid) empires had been the Euphrates River. The border was constantly contested. Most battles, and thus most fortifications, were concentrated in the hilly regions of the north, as the vast Arabian or Syrian Desert (Roman Arabia) separated the rival empires in the south. The only dangers expected from the south were occasional raids by nomadic Arab tribesmen. Both empires therefore allied themselves with small, semi-independent Arab principalities, which served as buffer states and protected Byzantium and Persia from Bedouin attacks. The Byzantine clients were the Ghassanids; the Persian clients were the Lakhmids. The Ghassanids and Lakhmids feuded constantly—which kept them occupied, but that did not greatly affect the Byzantines or the Persians. In the 6th and 7th centuries, various factors destroyed the balance of power that had held for so many centuries.

Revolt of the Arab client states (602)

The Byzantine clients, the Arab Ghassanids, converted to the Monophysite form of Christianity, which was regarded as heretical by the established Byzantine Orthodox Church. The Byzantines attempted to suppress the heresy, alienating the Ghassanids and sparking rebellions on their desert frontiers. The Lakhmids also revolted against the Persian king Khusrau II. Nu'man III (son of Al-Monder IV), the first Christian Lakhmid king, was deposed and killed by Khusrau II in 602, because of his attempt to throw off the Persian tutelage. After Khusrau's assassination, the Persian Empire fractured and the Lakhmids were effectively semi-independent. It is now widely believed that the annexation of the Lakhmid kingdom was one of the main factors behind the Fall of Sassanid dynasty, to the Muslim Arabs and the Islamic conquest of Persia, as the Lakhmids agreed to act as spies for the Muslims after being defeated in the Battle of Hira by Khalid ibn al-Walid.[13]

Byzantine–Sassanid War (612–629)

The Persian ruler Khosrau II (Parviz) defeated a dangerous rebellion within his own empire, the Bahram Chobin's rebellion. He afterward turned his energies towards his traditional Byzantine enemies, leading to the Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602–628. For a few years, he succeeded gloriously. From 612 to 622, he extended the Persian borders almost to the same extent that they were under the Achaemenid dynasty (550–330 BC), capturing Western states as far as Egypt, Palestine, and more.

The Byzantines regrouped and pushed back in 622 under Heraclius. Khosrau was defeated at the Battle of Nineveh in 627, and the Byzantines recaptured all of Syria and penetrated far into the Persian provinces of Mesopotamia. In 629, Khosrau's general Shahrbaraz agreed to peace, and the border between the two empires was once again the same as it was in 602.

Execution of Khosrau II

Khosrau II was executed in 628 and as a result, there were numerous claimants to the throne; from 628 to 632 there were ten kings and queens of Persia. The last, Yazdegerd III, was a grandson of Khosrau II and was said to be a mere child aged 8 years.[14]

During Prophet Muhammad's life

After the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah in 628, Islamic tradition holds that Prophet Muhammad sent many letters to the princes, kings, and chiefs of the various tribes and kingdoms of the time, inviting them to convert to Islam. These letters were carried by ambassadors to Persia, Byzantium, Ethiopia, Egypt, Yemen, and Hira (Iraq) on the same day.[15] This assertion has been brought under scrutiny by some modern historians of Islam—notably Grimme and Caetani.[16] Particularly in dispute is the assertion that Khosrau II received a letter from Prophet Muhammad, as the Sassanid court ceremony was notoriously intricate, and it is unlikely that a letter from what at the time was a minor regional power would have reached the hands of the Shahanshah.[17]

With regards to Persia, Muslim histories further recount that at the beginning of the seventh year of migration, Prophet Muhammad appointed one of his officers, Abdullah Huzafah Sahmi Qarashi, to carry his letter to Khosrau II inviting him to convert:

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.From Muhammad, the Messenger of Allah, to the great Kisra of Iran. Peace be upon him, who seeks truth and expresses belief in Allah and in His Prophet and testifies that there is no god but Allah and that He has no partner, and who believes that Prophet Muhammad is His servant and Prophet. Under the Command of Allah, I invite you to Him. He has sent me for the guidance of all people so that I may warn them all of His wrath and may present the unbelievers with an ultimatum. Embrace Islam so that you may remain safe. And if you refuse to accept Islam, you will be responsible for the sins of the Magi.[18]

There are differing accounts of the reaction of Khosrau II.[19] Nearly all assert that he destroyed the letter in anger; the variations concentrate on the extent and detail of his response..

Rise of the Caliphate

Prophet Muhammad died in June 632, and Abu Bakr took the title of Caliph and political successor at Medina. Soon after Abu Bakr's succession, several Arab tribes revolted, in the Ridda Wars (Arabic for the Wars of Apostasy). The Ridda Wars preoccupied the Caliphate until March 633, and ended with the entirety of the Arab Peninsula under the authority of the Caliph at Medina.

Whether Abu Bakr intended a full-out imperial conquest or not is hard to say. He did, however, set in motion a historical trajectory (continued later on by Umar and Uthman) that in just a few short decades would lead to one of the largest empires in history,[20] beginning with a confrontation with the Sassanid Empire under the general Khalid ibn al-Walid.

First invasion of Mesopotamia (633)

After the Ridda Wars, a tribal chief of north eastern Arabia, Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, raided the Persian towns in Mesopotamia (what is now Iraq). Abu Bakr was strong enough to attack the Persian Empire in the north-east and the Byzantine Empire in the north-west. There were three purposes for this conquest: 1. Along the borders between Arabia and these two great empires were numerous Arab tribes leading a nomadic life and forming a buffer-like state between the Persians and Romans. Abu Bakr hoped that these tribes might accept Islam and help their brethren in spreading it. 2. The Persian and Roman populations suffered with very high taxation laws; Abu Bakr believed that they might be persuaded to help the Muslims, who agreed to release them from the excessive tributes. 3. Two gigantic empires surrounded Arabia, and it was unsafe to remain passive with these two powers on its borders. Abu Bakr hoped that by attacking Iraq and Syria he might remove the danger from the borders of the Islamic State.[21] With the success of the raids, a considerable amount of booty was collected. Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha went to Medina to inform Caliph Abu Bakr about his success and was appointed commander of his people, after which he began to raid deeper into Mesopotamia. Using the mobility of his light cavalry he could easily raid any town near the desert and disappear again into the desert, into which the Sassanid army was unable to chase them. Al-Muthanna's acts made Abu Bakr think about the expansion of the Rashidun Empire.[22]

To be certain of a victory, Abu Bakr made two decisions concerning the attack on Persia: first, the invading army would consist entirely of volunteers; and second, to put in command of the army his best general: Khalid ibn al-Walid. After defeating the self-proclaimed prophet Musaylimah in the Battle of Yamama, Khalid was still at Al-Yamama when Abu Bakr sent him orders to invade the Sassanid Empire. Making Al-Hirah the objective of Khalid, Abu Bakr sent reinforcements and ordered the tribal chiefs of north eastern Arabia, Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, Mazhur bin Adi, Harmala and Sulma to operate under the command of Khalid along with their men. Around the third week of March 633 (first week of Muharram 12th Hijrah) Khalid set out from Al-Yamama with an army of 10,000.[22] The tribal chiefs, with 2,000 warriors each, joined Khalid; so he entered the Persian Empire with 18,000 troops.

After entering Mesopotamia with his army of 18,000, Khalid won decisive victories in four consecutive battles: the Battle of Chains, fought in April 633; the Battle of River, fought in the third week of April 633 AD; the Battle of Walaja, fought in May 633 (where he successfully used a double envelopment manoeuvre), and the Battle of Ullais, fought in the mid of May, 633 AD. The Persian court, already disturbed by internal problems, was thrown into chaos. In the last week of May 633, the important city of Hira fell to the Muslims after their victory in the Siege of Hira. After resting his armies, in June 633 Khalid laid siege to the city of Al Anbar, which surrendered in July 633 after a siege lasting a few weeks. Khalid then moved towards the south, and conquered the city of Ein ul Tamr after the Battle of Ein ut Tamr in the last week of July. At this point, most of what is now Iraq was under Islamic control.

Khalid got a call of help from northern Arabia at Daumat-ul-Jandal, where another Muslim Arab general, Ayaz bin Ghanam, was trapped among the rebel tribes. Khalid went to Daumat-ul-jandal and defeated the rebels in the Battle of Daumat-ul-jandal in the last week of August 633. Returning from Arabia, he got news of the assembling of a large Persian army. He decided to defeat them all separately to avoid the risk of being defeated by a large unified Persian army. Four divisions of Persian and Christian Arab auxiliaries were present at Hanafiz, Zumiel, Sanni and Muzieh. Khalid divided his army in three units, and attacked the Persian forces in well coordinated attacks from three different sides at night, starting from the Battle of Muzieh, then the Battle of Sanni, and finally the Battle of Zumail during November 633. These devastating defeats ended Persian control over Mesopotamia, and left the Persian capital Ctesiphon unguarded and vulnerable to Muslim attack. Before attacking the Persian capital, Khalid decided to eliminate all Persian forces in the south and west. He accordingly marched against the border city of Firaz, where he defeated the combined forces of the Sassanid Persians, the Byzantines and Christian Arabs in the Battle of Firaz in December 633. This was the last battle in his conquest of Mesopotamia. While Khalid was on his way to attack Qadissiyah (a key fort in the way to the Persian capital Ctesiphon), he received a letter from Caliph Abu Bakr and was sent to the Roman front in Syria to assume the command of the Muslim armies to conquer Roman Syria.[23]

Second invasion of Mesopotamia (636)

According to the will of Abu Bakr, Umar was to continue the conquest of Syria and Mesopotamia. On the northeastern borders of the Empire, in Mesopotamia, the situation was deteriorating day by day. During Abu Bakr's era, Khalid ibn al-Walid had been sent to the Syrian front to command the Islamic armies there. As soon as Khalid had left Mesopotamia with half his army of 9000 soldiers, the Persians decided to take back their lost territory. The Muslim army was forced to leave the conquered areas and concentrate on the border areas. Umar immediately sent reinforcements to aid Muthanna ibn Haritha in Mesopotamia under the command of Abu Ubaid al-Thaqafi.[4] The Persian forces defeated Abu Ubaid in the Battle of Bridge. However, later Persian forces were defeated by Muthanna bin Haritha in the Battle of Buwayb. In 635 Yazdgerd III sought alliance with Emperor Heraclius of the Eastern Roman Empire. Heraclius married his daughter (or, according to some traditions, his granddaughter) to Yazdegerd III, an old Roman tradition to show alliance. While Heraclius prepared for a major offence in the Levant, Yazdegerd, meanwhile, ordered the concentration of massive armies to push back the Muslims from Mesopotamia for good. The goal was well-coordinated attacks by both emperors, Heraclius in the Levant and Yazdegerd in Mesopotamia, to annihilate the power of their common enemy, Caliph Umar.

Battle of Qadisiyyah

Umar ordered his army to retreat to the bordering areas of Mesopotamia near the Arabian desert and began raising armies for another campaign into Mesopotamia. The Arab armies were concentrated near Medina, and owing to the critical situation Umar wished to command the army in person. This idea was opposed by the members of Majlis al Shura at Medina, who claimed that the two-front war required Umar's presence in Madinah. Umar appointed Saad ibn Abi Waqqas as commander for the campaign in Mesopotamia. Saad left Medina with his army in May 636 and arrived at Qadisiyyah in June.

While Heraclius launched his offensive in May 636, Yazdegerd was unable to muster his armies in time to provide the Byzantines with Persian support. Umar, allegedly aware of this alliance, capitalized on this failure: not wanting to risk a battle with two great powers simultaneously, he quickly moved to reinforce the Muslim army at Yarmouk to engage and defeat the Byzantines. Meanwhile, Umar ordered Saad to enter into peace negotiations with Yazdegerd III and invite him to Islam to prevent Persian forces from taking the field. Heraclius instructed his general Vahan not to engage in battle with the Muslims before receiving explicit orders; however, fearing more Arab reinforcements, Vahan attacked the Muslim army in the Battle of Yarmouk in August 636. Heraclius's Imperial army was routed.[24]

With the Byzantine threat ended, the Sassanid Empire was still a formidable power with vast manpower reserves, and the Arabs soon found themselves confronting a huge Persian army with troops drawn from every corner of the empire and commanded by its foremost generals. Among the troops were fearsome war elephants that the Persian commander brought with him for the sole purpose of vanquishing the Muslims. Within three months, Saad defeated the Persian army in the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, effectively ending Sassanid rule west of Persia proper.[25] This victory is largely regarded as a decisive turning point in Islam's growth: with the bulk of Persian forces defeated, Saad later conquered Babylon, Koosie, Bahrahsher and Madein. Ctesiphon, the Imperial capital of the Sassanid Empire, fell in March 637 after a siege of three months.

Conquest of Mesopotamia (636–638)

After the conquest of Ctesiphon, several detachments were immediately sent west to capture Qarqeesia and Heet the forts at the border of the Byzantine Empire. Several fortified Persian armies were still active north-east of Ctesiphon at Jalula and north of the Tigris at Tikrit and Mosul.

After withdrawal from Ctesiphon, the Persian armies gathered at Jalaula north-east of Ctesiphon. Jalaula was a place of strategic importance because from here routes led to Mesopotamia, Khurasan and Azerbaijan. The Persian forces at Jalula were commanded by General Mihran. His deputy was General Farrukhzad, a brother of General Rustam, who had commanded the Persian forces at the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah. As instructed by the Caliph Umar, Saad reported everything to Umar. The Caliph decided to deal with Jalula first. His plan was first to clear the way to the north before taking any decisive action against Tikrit and Mosul. Umar appointed Hashim ibn Utbah to the expedition of Jalula and Abdullah ibn Muta'am to conquer Tikrit and Mosul. In April 637, Hashim led 12,000 troops from Ctesiphon to win a victory over the Persians at the Battle of Jalula. He then laid siege to Jalula for seven months. After seizing a victory at Jalula, Abdullah ibn Muta'am marched against Tikrit and captured the city after fierce resistance and with the help of Christians. He next sent an army to Mosul which surrendered on the terms of the Jizya. With victory at Jalula and occupation of the Tikrit-Mosul region, Muslim rule in Mesopotamia was established.

After the conquest of Jalula, a Muslim force under Qa'qa marched in pursuit of the Persians. The Persian army that escaped from Jalaula took its position at Khaniqeen fifteen miles from Jalula on the road to Iran, under the command of General Mihran. Qa'qa defeated the Persian forces in the Battle of Khaniqeen and captured the city of Khaniqeen. The Persians withdrew to Hulwan. Qa'qa moved to Hulwan and laid siege to the city which was captured in January 638.[26] Qa'qa sought permission for operating deeper into Persian land, i.e. mainland Iran, but caliph Umar didn't approve the proposal and wrote a historic letter to Saad saying:

I wish that between the Suwad and the Persian hills there were walls which would prevent them from getting to us, and prevent us from getting to them.[27] The fertile Suwad is sufficient for us; and I prefer the safety of the Muslims to the spoils of war.

Raids of Persians in Mesopotamia (638–641)

By February 638 there was a lull in the fighting on the Persian front. The Suwad, the Tigris valley, and the Euphrates valley were now under the complete control of the Muslims. The Persians had withdrawn to Persia proper, east of the Zagros mountains. The Persians continued raiding Mesopotamia, which remained politically unstable. Nevertheless, it appeared as if this was going to be the dividing line between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sassanids. In the later part of the year 638 Hormuzan, who commanded one of the Persian corps at the Battle of Qadisiyyah and was one of the seven great chiefs of Persia, intensified his raids in Mesopotamia, Saad according to Umar's instructions undertook offensive actions against Hormuzan and Utbah ibn Ghazwan aided by Nouman ibn Muqarin attacked Ahvaz and forced Hormuzan to enter into a peace treaty with the Muslims according to which Ahvaz would remain in Hormuzan's possession and he would rule it as a vassal of the Muslims and would pay tribute. Hormuzan broke the treaty and revolted against the Muslims. Umar sent Abu Musa Ashaari, governor of Busra to deal with Hormuzan. Hormuzan was defeated and sought once again for peace. Umar accepted the offer and Hormuzan was again made vassal of the Muslims. This peace also proved short-lived once Hormuzan was reinforced by the fresh Persian troops sent by Emperor Yazdgerd III in late 640. The troops concentrated at Tuster north of Ahvaz. Umar sent Governor of Kufa, Ammar ibn Yasir, governor of Busra Abu Musa, and Nouman ibn Muqarin towards Tustar where Hormuzan was defeated, captured and sent to Madinah to Caliph Umar, where he apparently converted to Islam. He remained a useful adviser of Umar throughout the campaign of conquest of Persia. He is also considered to be the mastermind behind the assassination of Caliph Umar in 644. After the victory at Tustar, Abu Musa marched against Susa, a place of military importance, in January 641, which was captured after a siege of a couple of months. Next Abu Musa marched against Junde Sabur, the only place left of military importance in the Persian province of Khuzistan which surrendered to the Muslims after a siege of a few weeks.[28]

Battle of Nahavand (642)

After the conquest of Khuzistan, the Caliph Umar wanted peace. Though considerably weakened, the image of the Persian Empire as a fearsome superpower still resonated in the minds of the newly-ascendant Arabs, and Umar was wary of unnecessary military engagement with the Iranians. He wanted to leave the rest of Persia to the Iranians. Umar said:

I wish there was a mountain of fire between us and the Iranians, so that neither they could get to us, nor we to them.[29]

However, the pride of the imperial Persians had been hurt by the conquest of their land by the Arabs. They could not acquiesce in the occupation of their lands by the Arabs.[30]

After the defeat of the Persian forces at the Battle of Jalula in 637, Emperor Yazdgerd III went to Rey and from there moved to Merv where he set up his capital. From Merv, he directed his chiefs to conduct continuous raids in Mesopotamia to destabilize the Muslim rule. Within the next four years, Yazdgerd III felt powerful enough to challenge the Muslims once again for the throne of Mesopotamia. The Emperor sent a call to his people to drive away the Muslims from their lands. In response to the call, hardened veterans and young volunteers from all parts of Persia marched in large numbers to join the imperial standard and marched to Nihawand for the last titanic struggle between the forces of the Caliphate and Sassanid Persia. 100,000 Persian fighters assembled, commanded by Mardan Shah.

The Governor of Kufa, Ammar ibn Yasir, received intelligence of the Persian movements and concentration at Nihawand. He reported the matter to Umar. Although Umar had expressed a desire for Mesopotamia to be his easternmost frontier, he felt compelled to act given the concentration of the Persian army at Nihawand.[31] He believed thato long as Persia proper remained under Sassanid rule, Persian forces would continue raiding Mesopotamia with a view to one day recapturing the region. Hudheifa ibn Al Yaman was appointed commander of the forces of Kufa, and was ordered to march to Nihawand. Governor of Busra Abu Musa, was to march to Nihawand commanding his forces of Busra Nouman ibn Muqarrin marched from Ctesiphon to Nihawand while Umar decided to lead the army concentrated at Madinah in person and command the Muslims at the battle. Umar's decision to command the army in person was not well received by the members of Majlis al Shura at Madinah. It was suggested that Umar should command the campaign from Madinah, and should appoint an astute military commander to lead the Muslims at Nihawand. Umar appointed Mugheera ibn Shuba as commander of the forces concentrated at Madinah and appointed Nouman ibn Muqarrin as commander in chief of the Muslims at Nihawand. The Muslim army left for Nihawand and first concentrated at Tazar, and then moved to Nihawand and defeated the Persian forces at the Battle of Nihawand in December 642. Nouman died in action, and as per Umar's instructions Hudheifa ibn Al Yaman became new commander in chief. After the victory at Nihawand, the Muslim army captured the whole district of Hamadan after feeble resistance by the Persians.[29]

Conquest of Persia (642–651)

After several years, Caliph Umar adopted a new offensive policy,[32] preparing to launch a full-scale invasion of what remained of the Sassanid Empire. The Battle of Nihawand was one of the most decisive battles in Islamic history.[33] and proved to be the key to Persia. After the devastating defeat at Nihawand, the last Sassanid emperor, Yazdegerd III, fled to different parts of Persia to raise a new army, with limited degrees of success, with Umar trying to capture him.

Strategic planning for the conquest of Persia

Umar decided to strike the Persians immediately after their defeat at Nihawand, when he had gained a psychological advantage over them. Umar had to decide which of the following three to conquer first: Fars in the south, Azerbaijan in the north or Isfahan in the center. Umar chose Isfahan, as it was the heart of the Persian Empire and a conduit for supply and communication lines between Sassanid garrisons in various Persian provinces. In other words, capturing Isfahan would isolate Fars and Azerbaijan from Khurasan. After having captured the heartland of Persia, that is Fars and Isfahan, the next attacks would be simultaneously launched against Azerbaijan, the North Western province, and Sistan, the most eastern province of the Persian Empire.[33] The conquest of those provinces would leave Khorasan, the stronghold of Emperor Yazdegerd III, isolated and vulnerable. In the last phase of this campaign, Khorasan was to be attacked, completing the conquest of Sassanid Persia.

The plan was formulated and preparations were completed by January 642. The success of plan depended upon how effectively Umar would be able to coordinate these attacks from Madinah, about 1500 kilometers from the battlefields in Persia and upon the skills and abilities of his field commanders. Umar appointed his best field commanders to conquer the Sassanid Empire and bring down his most formidable foe, Yazdegerd III. The campaign saw a different pattern in command structure. Instead of appointing a single field commander to campaign across the Persian lands, Umar appointed several commanders, each assigned a different mission. Once the mission would end the commander would become an ordinary soldier under the command of the new field commander for the latter's mission. The purpose of this strategy was to allow commanders to mix in with their soldiers and to remind them that they are like everyone else; command is only given to those most competent, and once the battle is over, the commander returns to his previous position.

In 638, Caliph Umar dismissed Khalid, who chose not to rebel against the dismissal. In 642 at the eve of the conquest of Persia, Umar, wanting to give a moral boost to his troops, decided to reinstall Khalid as new field commander against Persia.[33] Khalid's reputation as the conqueror of Eastern Roman provinces demoralized the Persian commanders, most of whom had already been defeated by him during his conquest of Mesopotamia in 633.

Umar wanted a decisive victory early in the campaign to boost the morale of his troops, while demoralizing the Persians. Before Umar could issue orders of reappointment, Khalid, residing in Emesa, died. In various campaigns in Persia, Umar even appointed the commanders of the wings, the center and the cavalry of the army. Umar strictly instructed his commanders to consult him before making any decisive move in Persia. All the commanders, before starting their assigned campaigns, were instructed to send a detailed report of the geography and terrain of the region and the position of the Persian garrisons, forts, cities and troops in it. Umar then would send them a detailed plan of how he wanted this region to be captured. Only the tactical issues were left to the field commanders to be tackled in accordance with the situation they faced at their fronts.[34] Umar appointed the best available and well reputed commanders for the campaign.[33][35]

Conquest of Central Persia

The preparation and planning of the conquest of the Persian Empire was completed by early 642. Umar appointed Abdullah ibn Uthman, commander of the Muslim forces, to invade Isfahan. From Nihawand, Nu'man marched to Hamadan, which was already in Muslim hands. Once Hamadan was captured, Nu'man marched 230 miles southeast against the city Isfahan and defeated an Sasanian army under the command of Shahrvaraz Jadhuyih and other notable Sasanian generals. Shahrvaraz Jadhuyih, along with another Sasanian general was killed during the battle.[36] After his victory at Isfahan, he laid siege to the city; there the Muslim army was reinforced by fresh troops from Busra and Kufa under the command of Abu Musa Ashaari and Ahnaf ibn Qais.[37] The siege continued for a few months and finally the city surrendered.

In 651, Nu'aym marched northeast to Rey, Iran, about 200 miles from Hamadan, and laid siege to the city, which surrendered after fierce resistance. Nu'aym then marched 150 miles northeast towards Qom, which was captured without much resistance. This was the outermost boundary of the Isfahan region. Further northeast of it was Khurasan, and southeast of it lay Sistan. Meanwhile, Hamadan and Rey had rebelled. Umar sent Nu'aym ibn Muqaarin, brother of late Nu'man ibn Muqaarin, who was the Muslim commander at Nihawand, to crush the rebellion and to clear the westernmost boundaries of Isfahan. Nu'aymm marched towards Hamadan from Isfahan. A bloody battle was fought and Hamadan was recaptured by the Muslims. Nu'aym next moved to Rey. There too the Persians resisted and were defeated outside the fort, and the city was recaptured by the Muslims.[38] The Persian citizens sought for peace and agreed to pay the Jizya. From Rey, Nu'aym moved north towards Tabaristan, which lay south of the Caspian Sea.[38] The ruler of Tabaristan then signed a peace treaty with the Caliphate.

Conquest of Fars

First Muslim invasion and the successful Sasanian counter-attack

The Muslim invasion of Fars began in 638/9, when the Rashidun governor of Bahrain, al-'Ala' ibn al-Hadrami, after having defeated some rebellious Arab tribes, seized an island in the Persian Gulf. Although al-'Ala' and the rest of the Arabs had been ordered to not invade Fars or its surrounding islands, he and his men continued their raids into the province. Al-'Ala quickly prepared an army which was divided into three groups, one under al-Jarud ibn Mu'alla, the second under al-Sawwar ibn Hammam and the third under Khulayd ibn al-Mundhir ibn Sawa. When the first group entered Fars, it was quickly defeated and al-Jarud was killed.

The same thing soon happened to the second group. However, things proved to be more fortunate with the third group; Khulayd managed to keep them on bay, but was unable to withdraw back to Bahrain as the Sassanians were blocking his way at the sea. Umar, founding out about al-'Ala's invasion of Fars, had him replaced with Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas as the governor of Bahrain. Umar then ordered Utbah ibn Ghazwan to send reinforcements to Khulayd. When the reinforcements arrived, Khulayd and some of his men managed successfully to withdraw back to Bahrain, while the rest withdrew to Basra.

Second and last Muslim invasion

In ca. 643, Uthman ibn Abi al-'As seized Bishapur, and made a peace treaty with the inhabitants of the city. In 644, al-'Ala' once again attacked Fars from Bahrain, reaching as far as Estakhr, until he was repelled by the governor (marzban) of Fars, Shahrag. Some time later, Uthman ibn Abi al-'As managed to establish a military base at Tawwaj, and shortly defeated and killed Shahrag near Rew-shahr (however other sources states that it was his brother who did it). A Persian convert to Islam, Hormoz ibn Hayyan al-'Abdi, was shortly sent by Uthman ibn Abi al-'As to attack a fortress known as Senez on the coast of Fars. After the accession of Uthman ibn Affan as the new Rashidun Caliph on 11 November, the inhabitants of Bishapur under the leadership of Shahrag's brother declared independence, but were defeated. However the date for this revolt mains disputed, as the Persian historian al-Baladhuri states that it occurred in 646.

In 648, 'Abd-Allah ibn al-'Ash'ari forced the governor of Estakhr, Mahak, to surrender the city. However, this was not the final conquest of Estakhr, as the inhabitants of the city would later rebel in 649/650 while its newly appointed governor, 'Abd-Allah ibn 'Amir was trying to capture Gor. The military governor of the province, 'Ubayd Allah ibn Ma'mar, was defeated and killed. In 650/651, Yazdegerd went to Estakhr and tried to plan an organized resistance against the Arabs, and after some time he went to Gor, but Estakhr failed to put up a strong resistance, and was soon sacked by the Arabs, who killed over 40,000 defenders. The Arabs then quickly seized Gor, Kazerun and Siraf, while Yazdegerd III fled to Kerman. This ended the Muslim conquest of Pars, although the inhabitants of the province would later rebel several times against the Arabs.

Conquest of Southeastern Persia (Kerman and Makran)

The expedition to Kerman was sent roughly at the same time when the expeditions to Sistan and Azerbaijan were sent. Suhail ibn adi was given command of this expedition. Suhail marched from Busra in 643; passing from Shiraz and Persepolis he joined with other Muslim armies and marched against Kerman, which was subdued after a pitched battle with local garrisons. Further east of Kerman lay Makran in what is now a part of present-day western Pakistan. The Raja of Rasil concentrated huge armies from Sindh and Balochistan to halt the advance of the Muslims. Suhail was reinforced by Usman ibn Abi Al Aas from Persepolis, and Hakam ibn Amr from Busra. The combined forces defeated Raja Rasil at the Battle of Rasil, who retreated to the eastern bank of the River Indus. Further east from the Indus River laid Sindh.[39] Umar, after knowing that Sindh was a poor and relatively barren land, disapproved Suhail's proposal to cross the Indus River.[38] For the time being, Umar declared the Indus River, a natural barrier, to be the eastern most frontier of his domain. This campaign came to an end in mid 644.[35]

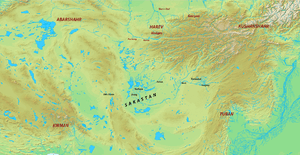

Conquest of Sakastan

Already during the reign of Umar, Sakastan suffered from raids by the Arabs. However, the first real invasion took place in 650, when Abd-Allah ibn Amir, after having secured his position in Kerman, sent an army under Mujashi ibn Mas'ud to Sakastan. After having crossed the Dasht-i Lut desert, Mujashi ibn Mas'ud arrived to Sakastan. However, he suffered a heavy defeat and was forced to retreat.[40]

One year later, Abd-Allah ibn Amir sent an army under Rabi ibn Ziyad Harithi to Sakastan. After some time, he reached Zaliq, a border town between Kirman and Sakastan, where he forced the dehqan of the town to acknowledge Rashidun authority. He then did the same at the fortress of Karkuya, which had a famous fire temple, which is mentioned in the Tarikh-i Sistan.[41] He then continued to seize more land in the province. He thereafter besieged the capital Zrang, and after a heavy battle outside the city, its governor Aparviz surrendered. When Aparviz went to Rabi ibn Ziyad to discuss about the conditions of a treaty, he saw that he was using the bodies of two dead soldiers as a chair. This horrified Aparviz, who in order to spare the inhabitants of Sakastan from the Arabs, made peace with them in return for a heavy tribute of 1 million dirhams, including 1,000 slave boys (or girls) bearing 1,000 golden vessels.[41][42] Rabi ibn Ziyad was then appointed as the governor of province.[43]

18 months later, Rabi was summoned to Basra, and was replaced by 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura as governor. The inhabitants of Sakastan used this opportunity to rebel and defeat the Muslim garrison of Zrang. When 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura reached Sakastan, he suppressed the rebellion and defeated the Zunbils of Zabulistan, seizing Bust and a few cities in Zabulistan.[41][43]

Conquest of Azerbaijan

The conquest of Iranian Azerbaijan started in 651.[44] It was part of a simultaneous attack launched against the north, south and east of Persia, after capturing Isfahan and Fars. These coordinated multi-pronged attacks by Caliph Umar paralyzed the whole of what then remained of the Persian Empire. Expeditions were sent against Kerman and Makran in the southeast, against Sistan in the northeast and against Azerbaijan in the northwest. Hudheifa ibn Al Yaman was appointed commander to conquer Azerbaijan. Hudheifa marched from Rey in central Persia to Zanjan, a stronghold of the Persians in the north. Zanjan was a well defended fortified town. The Persians came out of the city and gave battle. Hudheifa defeated the Persian garrison and captured the city, and according to Caliph Umar's order, the civilians who sought for peace were given peace on the usual terms of the Jizya.[45] From Zanjan, Hudheifa marched to Ardabil which surrendered peacefully and Hudheifa continued his march north along the western coast of the Caspian Sea and captured Bab al-Abwab by force.[35] At this point Hudheifa was recalled by Caliph Umar, with Bukair ibn Abdullah and Utba ibn Farqad succeeding him. They were sent to carry out a two pronged attack against Azerbaijan: Bukair was to march north along the western coast of the Caspian Sea while Uthba was to march directly into the heart of Azerbaijan. On his way north Bukair was halted by a large Persian force under Isfandiyar, the son of Farrukhzad. A pitched battle was fought, after which Isfandiyar was defeated and captured. In return for the safety of his life, he agreed to surrender his estates in Azerbaijan and persuade others toward submission to Muslim rule.[38] Uthba ibn Farqad then defeated Bahram, brother of Isfandiyar. He too sought for peace. A pact was drawn according to which Azerbaijan was surrendered to Caliph Umar on usual terms of paying the annual Jizya. The expedition commenced some time in late 651.

Conquest of Armenia

.jpg)

Byzantine Armenia was already conquered in 638–639. Persian Armenia lay north of Azerbaijan. By now, except for Khurasan and Armenia, the whole of the Persian Empire was under Umar's control and Emperor Yazdegred III was on the run. However, Umar refused to take any chances; he never perceived the Persians as being weak and weary. The fact that Umar didn't underestimate the Persians is the secret behind the brilliant and speedy conquest of the Persian Empire. Again Umar decided to send simultaneous expeditions to the far north-east and north-west of the Persian Empire. An expedition was sent to Khurasan in late 643 and at the same time an expedition was launched against Armenia. Bukair ibn Abdullah, who had recently subdued Azerbaijan, was assigned a mission to capture Tiflis. From Bab at the western coast of the Caspian Sea, Bukair continued his march north. Umar decided to practice his traditional and successful strategy of multi-pronged attacks. While Bukair was still miles away from Tiflis, Umar instructed him to divide his army into three corps. Umar appointed Habib ibn Muslaima to capture Tiflis, Abdulrehman to march north against the mountains and Hudheifa to march against the southern mountains. Habib captured Tiflis and the region up to the eastern coast of the Black Sea. Abdulrehman marched north to the Caucasus Mountains and subdued the tribes. Hudheifa marched south-west to the mountainous region and subdued the local tribes. The advance into Armenia came to an end with the death of Caliph Umar in November 644. By then almost the whole of the South Caucasus was captured.[46]

Conquest of Khorasan

Khorasan was the second largest province of the Sassanid Empire. It stretched from what is now northeastern Iran, northwestern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan. Its capital was Balkh, in northern Afghanistan. In 651 the mission of conquering Khurasan was assigned to Ahnaf ibn Qais.[35] Ahnaf marched from Kufa and took a short and less frequented route via Rey and Nishapur. Rey was already in Muslim hands and Nishapur surrendered without resistance. From Nishapur Ahnaf marched to Herat which is in western Afghanistan. Herat was a fortified town, the Siege of Herat lasted for a few months before surrendering. With the surrender of Herat, the whole of southern Khurasan came under Muslim control. With Herat under his firm control, Ahnaf marched north directly to Merv, in present Turkmenistan.[47] Merv was the capital of Khurasan and here Yazdegred III held his court. On hearing of the Muslim advance, Yazdegred III left for Balkh. No resistance was offered at Merv, and the Muslims occupied the capital of Khurasan without firing a shot. Ahnaf stayed at Merv and waited for reinforcement from Kufa. Meanwhile, Yazdgird had also gathered considerable power at Balkh and also sought alliance with the Khan of Farghana, who personally led the Turkish contingent to help Yazdegred III. Umar ordered that Yazdgird's allied forces should be weaken by breaking up the alliance with the Turks. Ahnaf successfully broke up the alliance and the Khan of Farghana pulled back his forces realizing that fighting with the Muslims was not a good idea and that it might endanger his own kingdom. Yazdgird's army was defeated at the Battle of Oxus River and retreated across the Oxus to Transoxiana. Yazdegred III had a narrow escape and fled to China. Balkh was occupied by the Muslims, and with this occupation the Persian war was over. The Muslims had now reached the outermost frontiers of Persia. Beyond that lay the lands of the Turks and still further lay China. The old mighty empire of the Sassanids had ceased to exist. Ahnaf returned to Marv and sent a detail report of operations to Umar, a historic letter Umar was anxiously waiting for, subject of which was the downfall of the Persian Empire, and with which permission was sought to cross the Oxus river and invade Transoxiana. Umar ordered Ahnaf to desist and instead to consolidate his power south of Oxus.

Persian rebellion and reconquest

Caliph Umar was assassinated in November 644 by a Persian slave named Piruz Nahavandi. The assassination is often seen by various historians as a Persian conspiracy against Umar.[35] Hormuzan is said to have masterminded this plot. Caliph Uthman ibn Affan (644–656) succeeded Umar. During his reign almost the whole of the former Sassanid empire's territory rebelled from time to time until 651, until the last Sassanid emperor was assassinated near Merv ending the Sassanid dynasty and Persian resistance to the Muslims. Caliph Uthman therefore had to send several military expeditions to crush the rebellions and recapture Persia and their vassal states. The Empire expanded beyond the borders of the Sassanid Empire in Transoxiana, Baluchistan and the Caucasus. The main rebellion was in the Persian provinces of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Fars, Sistan (in 649), Khorasan (651), and Makran (650).[48]

End of the Sassanid dynasty

Yazdegerd III, after being defeated in several battles, was unable to raise another army and became a hunted fugitive. He kept fleeing from one district to another until a local miller killed him for his purse at Merv in 651.[49] For many decades to come, this was the easternmost limit of Muslim rule.

Persia under Muslim rule

According to Bernard Lewis:

Arab Muslims conquests have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders. Both perceptions are of course valid, depending on one's angle of vision… Iran was indeed Islamized, but it was not Arabized. Persians remained Persians. And after an interval of silence, Iran reemerged as a separate, different and distinctive element within Islam, eventually adding a new element even to Islam itself. Culturally, politically, and most remarkable of all even religiously, the Iranian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i Ajam. It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna.[50]

Administration

Under Umar and his immediate successors, the Arab conquerors attempted to maintain their political and cultural cohesion despite the attractions of the civilizations they had conquered. The Arabs initially settled in the garrison towns rather than on scattered estates. The new non-Muslim subjects were protected by the state and known as dhimmi (meaning protected), and were to pay a special tax, the jizya (tribute), which was calculated per individual at varying rates, usually two dirhams for able bodied men of military age, in return for their exemption from military services. Women and Children were exempted from the Jizya.[51] Mass conversions were neither desired nor allowed, at least in the first few centuries of Arab rule[52][53][54] Caliph Umar had liberal policies towards dhimmis. These policies were adopted to make the conquered less prone to rise up against their new masters and thus making them more receptive to Arab colonization, as it for the time being gave them release from the intolerable social inferiority system of the old Sassanid regime.[55] Umar is reported to have issued the following instructions about the protected people:

Make it easy for him, who can not pay tribute; help him who is weak, let them keep their titles, but do not give them our kuniyat (Arabic traditional nicknames or titles).[56]

Umar's liberal policies were continued by at least his immediate successors. In his dying charge to his successor he is reported to have said:

I charge the caliph after me to be kind to the dhimmis, to keep their covenant, to protect them and not to burden them over their strength.[56]

Practically the Jizya replaced poll taxes imposed by the Sassanids, which tended to be much higher than the Jizya. In addition to the Jizya the old Sassanid land tax (Known in Arabic as Kharaj) was also adopted. Caliph Umar is said to have occasionally set up a commission to survey the taxes in order to check that they wouldn't be more than the land could bear.[57] It is narrated that Zoroastrians were subjected to humiliation and ridicule when paying the Jizya in order to make them feel inferior,.[58]

For at least under Rashiduns and early Ummayads, the administrative system of the late Sassanid period was largely retained. This was a pyramidal system where each quarter of the state was divided into provinces, the provinces into districts, and the districts into sub-districts. Provinces were called ustan (Middle Persian ostan), the districts shahrs, centered upon a district capital known as shahristan. The subdistricts were called tasok in Middle Persian, which was adopted as tassuj (plural tasasij) into Arabic.

Religion

After the Muslim conquest of Persia, Zoroastrians were given dhimmi status and subjected to persecutions; discrimination and harassment began in the form of sparse violence.[59][60] Zoroastrians were made to pay an extra tax called Jizya, failing which they were either killed, enslaved or imprisoned. Those paying Jizya were subjected to insults and humiliation by the tax collectors.[61][62][63] Zoroastrians who were captured as slaves in wars were given their freedom if they converted to Islam.[61][64]

Muslim leaders in their effort to win converts encouraged attendance at Muslim prayer with promises of money and allowed the Quran to be recited in Persian instead of Arabic so that it would be intelligible to all.[65] Islam was readily accepted by Zoroastrians who were employed in industrial and artisan positions because, according to Zoroastrian dogma, such occupations that involved defiling fire made them impure.[65] Moreover, Muslim missionaries did not encounter difficulty in explaining Islamic tenets to Zoroastrians, as there were many similarities between the faiths. According to Thomas Walker Arnold, for the Persian, he would meet Ahura Mazda and Ahriman under the names of Allah and Iblis.[65] In Afghanistan, Islam was spread due to Umayyad missionary efforts particularly under the reign of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and Umar ibn AbdulAziz.[65]

There were also large and thriving Christian and Jewish communities, along with smaller numbers of Buddhists and other groups. However, there was a slow but steady movement of the population towards Islam. The nobility and city-dwellers were the first to convert. Islam spread more slowly among the peasantry and the dihqans, or landed gentry. By the late 10th century, the majority of the Persians had become Muslim. Until the 15th century, most Persian Muslims were Sunni Muslims, though today Iran is known as a stronghold of the Shi'a Muslim faith, recognizing Islam as their religion and the prophet's son in law, Ali as an enduring symbol of justice.

According to Amoretti in Cambridge History of Islam, the conquestors brought with them a new religion and a new language, but they did not use force to spread it. While giving freedom of choice, however, the conquestors designated privileges for those who converted.[66]

Language

During the Rashidun Caliphate, the official language of Persia remained Persian, just as the official languages of Syria and Egypt remained Greek and Coptic. However, during the Ummayad Caliphate, the Ummayads imposed Arabic as the primary language of their subjected people throughout their empire, displacing their indigenous languages. Although an area from Iraq to Morocco speaks Arabic to this day, Middle Persian proved to be much more enduring. Most of its structure and vocabulary survived, evolving into the modern Persian language. However, Persian did incorporate a certain amount of Arabic vocabulary, especially words pertaining to religion, and it switched from the Pahlavi Aramaic alphabet to a modified version of the Arabic alphabet.[67] Today Persian is spoken officially in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.

Urbanisation

The Arab conquest of Persia led to a period of extreme urbanisation in Iran, starting with the ascension of the Abbasid dynasty and ending in the 11th century CE.[68] This was particularly true for the eastern parts of the country, for regions like Khorasan and Transoxiana.[69] During this period, Iran saw the development of massive metropolises, some reaching population numbers of up to 200,000 people.[68] Before this period, the important Persian cities had been situated outside of Persia proper, especially in Mesopotamia. This period of extreme urbanisation was followed in the 11th century by a collapse of the Iranian economy, which led to large scale emigrations of Iranians into Central Asia, India, the rest of the Middle East, and Anatolia. This catastrophe has been cited by some as reason for the Persian language becoming widespread throughout Central Asia and large parts of the Middle East.[70]

See also

- Islamization of Iran

- Arab rule in Georgia

- Emirate of Tbilisi

- Arab-Byzantine Wars

- History of Arabs in Afghanistan

- History of Iran

- Military history of Iran

- Fall of Sassanid dynasty

- Muslim conquests

- Islamic conquest of Afghanistan

- Muslim conquest of Transoxiana

- Spread of Islam

- Islam in Iran

References

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), pp. 469

- ↑ "ʿARAB ii. Arab conquest of Iran". iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ "Between Memory and Desire". google.nl.

- 1 2 The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch: 1 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4

- ↑ Milani A. Lost Wisdom. 2004 ISBN 978-0-934211-90-1 p.15

- ↑ (Balāḏori, Fotuḥ, p. 421; Biruni, Āṯār, p. 35)

- ↑ Mohammad Mohammadi Malayeri, Tarikh-i Farhang-i Iran (Iran's Cultural History). 4 volumes. Tehran. 1982.

- ↑ ʻAbd al-Ḥusayn Zarrīnʹkūb (2000) [1379]. Dū qarn-i sukūt : sarguz̲asht-i ḥavādis̲ va awz̤āʻ-i tārīkhī dar dū qarn-i avval-i Islām (Two Centuries of Silence). Tihrān: Sukhan. OCLC 46632917.

- ↑ Arthur Christensen, L’Iran sous les Sassanides, Copenhagen, 1944 (Christensen 1944).

- ↑ Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire, (I.B.Tauris, 2009), 3.

- ↑ Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, I.B. Tauris, 2008.

- 1 2 Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, I.B. Tauris, 2008. (p. 4)

- ↑ Iraq After the Muslim Conquest By Michael G. Morony, pg. 233

- ↑ "SASANIAN DYNASTY". iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ "The Events of the Seventh Year of Migration". Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Leone Caetani, Annali dell' Islam, vol. 4, p. 74

- ↑ Leone Caetani, Annali dell'Islam, vol. 2, chapter 1, paragraph 45–46

- ↑ Tabaqat-i Kubra, vol. I, page 360; Tarikh-i Tabari, vol. II, pp. 295, 296; Tarikh-i Kamil, vol. II, page 81 and Biharul Anwar, vol. XX, page 389

- ↑ "Kisra", M. Morony, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. V, ed.C.E. Bosworth, E.van Donzel, B. Lewis and C. Pellat, (E.J.Brill, 1980), 185.

- ↑ Fred M. Donner, "Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam", Harvard University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6

- ↑ Akbar Shah Najeebabadi, The history of Islam. B0006RTNB4.

- 1 2 Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 554.

- ↑ Akram, chapters 19–26.

- ↑ Serat-i-Hazrat Umar-i-Farooq, by Mohammad Allias Aadil, page no:67

- ↑ Akram, A.I. "5". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ↑ Akram, A. I. "6". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ↑ Haykal, Muhammad Husayn. "5". Al Farooq, Umar. p. 130.

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch: 7 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4, 9780195977134

- 1 2 Akram, A.I. "8". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ↑ Petersen, Anderew. Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. p. 120.

- ↑ Wilcox, Peter. Rome's Enemies 3: Parthians and Sassanids. Osprey Publishing. p. 4.

- ↑ Al Farooq, Umar By Muhammad Husayn Haykal. chapter 18 page 130

- 1 2 3 4 Akram, A.I. "10". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ↑ The History of Al-Tabari: The Challenge to the Empires, Translated by Khalid Yahya Blankinship, Published by SUNY Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-7914-0852-0,

- 1 2 3 4 5 Muhammad Husayn Haykal. "19". Al Farooq, Umar. p. 130.

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), p. 247

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:11 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4,

- 1 2 3 4 The History of Al-Tabari: The Challenge to the Empires, Translated by Khalid Yahya Blankinship, Published by SUNY Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-7914-0852-0

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:13 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4,

- ↑ Marshak & Negmatov 1996, p. 449.

- 1 2 3 Zarrinkub 1975, p. 24.

- ↑ Morony 1986, pp. 203-210.

- 1 2 Marshak & Negmatov 1996, p. 450.

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), p. 468

- ↑ Akram, A.I. "15". The Muslim Conquest of Persia. ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4.

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:16 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4,

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:17 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4,

- ↑ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:19 ISBN 978-0-19-597713-4,

- ↑ "Iran". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard. "Iran in history". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Longman. p. 68.

- ↑ Frye, R.N (1975). The Golden Age of Persia. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84212-011-8.

- ↑ Tabari. Series I. pp. 2778–9.

- ↑ Boyce, Mary (1979), Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-23903-5 pg.150

- ↑ Landlord and peasant in Persia: a study of land tenure and land revenue. By Ann K. S. Lambton, pg.17.

- 1 2 The Caliphs and Their Non-Muslim Subjects. By A. S. Tritton, pg.138.

- ↑ The Caliphs and Their Non-Muslim Subjects. By A. S. Tritton, pg.139.

- ↑ Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices. Routledge, 2001. p. 146. ISBN 9780415239028.

- ↑ Spencer 2005, p. 168

- ↑ Stepaniants 2002, p. 163

- 1 2 Boyce 2001, p. 148

- ↑ Lambton 1981, p. 205

- ↑ Meri & Bacharach 2006, p. 878

- ↑ "History of Zoroastrians in Islamic Iran". FEZANA Religious Education. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg.170–180

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Iran Volume4 The Period from the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs, p. 483

- ↑ "What is Persian?". The center for Persian studies. Archived from the original on 10 December 2005.

- 1 2 Professor R. Bulliet on Iran's urbanisation (1h 10m 29s) on YouTube

- ↑ "Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th-13th centuries". google.nl.

- ↑ Professor R. Bulliet on Iran's urbanisation (1h 11m 48s) on YouTube

Sources

- Bashear, Suliman (1997). Arabs and Others in Early Islam. Darwin Press. ISBN 978-0-87850-126-7.

- Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8.

- Daniel, Elton (2001). The History of Iran. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30731-7.

- Donner, Fred (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-05327-1.

- Morony, M. (1987). "Arab Conquest of Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 2, ANĀMAKA – ĀṮĀR AL-WOZARĀʾ.

- Sicker, Martin (2000). The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-96892-2.

- Spuler, Bertold; M. Ismail Marcinkowski (translator), Clifford Edmund Bosworth (foreword) (2003). Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, India and Early Ottoman Turkey. Singapore: Pustaka Nasional. ISBN 978-9971-77-488-2. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Zarrin'kub, Abd al-Husayn (1999). Ruzgaran: tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi. Sukhan. ISBN 978-964-6961-11-1.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 0857716662.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Zarrinkub, Abd al-Husain (1975). "The Arab conquest of Iran and its aftermath". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- Morony, M. (1986). "ʿARAB ii. Arab conquest of Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 2. pp. 203–210.

- Christensen, Peter (1993). The Decline of Iranshahr: Irrigation and Environments in the History of the Middle East, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1500. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 1–351. ISBN 9788772892597.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2005). "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1997). "Sīstān". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden, and New York: BRILL. pp. 681–685. ISBN 9789004082656.

- Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran’s National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2011). "SISTĀN ii. In the Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Marshak, B.I., and N.N. Negmatov. "Sogdiana." History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Eds. B.A. Litvinsky, Zhang Guang-da and R. Shabani Samghabadi. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996. ISBN 92-3-103211-9

- A. K. S., Lambton (1999). "FĀRS iii. History in the Islamic Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IX, Fasc. 4. pp. 337–341.

- Daryaee, Touraj. "Collapse of Sasanian Power in Fars". Fullerton, California: California State University. pp. 3–18 https://www.academia.edu/956827/Collapse_of_Sasanian_Power_in_Fars. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

- History of Iran: Islamic Conquest from the Iran Chamber Society.

- The Arab conquests at History World.

- Muslim Conquest of Persia at Mecca Books.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||