Iridoid

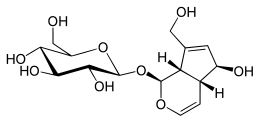

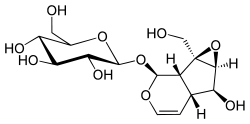

Iridoids are bicyclic cis-fused cyclopentane-pyrans. They are derived from 8-Oxogeranial, and can be further metabolized to loganin, secologanin and strictosidine (Geu-Flores seminar 2013).

The chemical structure is exemplified by iridomyrmecin, a defensive chemical produced by the Iridomyrmex genus, for which iridoids are named. Cleavage of a bond in the cyclopentane ring gives rise to a subclass known as secoiridoids, such as oleuropein and amarogentin. Iridoids are secondary metabolites typically found in plants as glycosides, most often bound to glucose.

Occurrence

Iridoids are found in many medicinal plants and may be responsible for some of their pharmaceutical activities. Isolated and purified, iridoids exhibit a wide range of bioactivities including cardiovascular, antihepatotoxic, choleretic, hypoglycemic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, antispasmodic, antitumor, antiviral, immunomodulator, and purgative activities.[1][2]

The iridoids are produced by plants primarily as a defense against herbivores or against infection by microorganisms. The Variable Checkerspot butterfly also uses iridoids obtained through its diet as a defense against avian predators.[3] To humans and other mammals, iridoids are often characterized by a deterrent bitter taste.

Aucubin and catalpol are two of the most common iridoids in the plant kingdom. Iridoids are prevalent in the plant subclass Asteridae, such as Ericaceae, Loganiaceae, Gentianaceae, Rubiaceae, Verbenaceae, Lamiaceae, Oleaceae, Plantaginaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Valerianaceae, and Menyanthaceae.

Biosynthesis

The iridoid ring scaffold is synthesized, in plants, by the enzyme iridoid synthase.[4] In contrast with other monoterpene cyclases , iridoid synthase uses 8-oxogeranial as a substrate. The enzyme uses a two-step mechanism, with an initial NADPH-dependent reduction step followed by a cyclization step that occurs through either a Diels-Alder reaction or an intramolecular Michael addition.[4]

References

- ↑ Dinda, Biswanath; Debnath, Sudhan; Harigaya, Yoshihiro (2007). "Naturally Occurring Iridoids. A Review, Part 1". CHEMICAL & PHARMACEUTICAL BULLETIN 55 (2): 159–222. doi:10.1248/cpb.55.159.

- ↑ Tundis, Rosa; Loizzo, Monica; Menichini, Federica; Statti, Giancarlo; Menichini, Francesco (1 April 2008). "Biological and Pharmacological Activities of Iridoids: Recent Developments". Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 8 (4): 399–420. doi:10.2174/138955708783955926.

- ↑ Bowers, M. Deane (March 1981). "Unpalatability as a Defense Strategy of Western Checkerspot Butterflies (Euphydryas scudder, Nymphalidae)". Evolution 35 (2): 367. doi:10.2307/2407845.

- 1 2 Geu-Flores, F.; Sherden, N. H.; Courdavault, V.; Burlat, V.; Glenn, W. S.; Wu, C.; Nims, E.; Cui, Y.; O'Connor, S. E. (2012). "An alternative route to cyclic terpenes by reductive cyclization in iridoid biosynthesis". Nature 492 (7427): 138–142. doi:10.1038/nature11692. PMID 23172143.

Further reading

Moreno-Escobar, Jorge A.; Alvarez, Laura; Rodrıguez-Lopez, Veronica; Marquina Bahena, Silvia (2 March 2013). "Cytotoxic glucosydic iridoids from Veronica Americana". Elsevier 6 (4): 610–613. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2013.07.017.