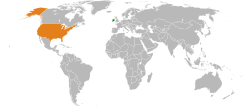

Ireland–United States relations

|

|

Ireland |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Irish Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Dublin |

Ireland–United States relations refers to the current and historical bilateral relationship between Ireland and the United States.

According to the government of the United States, U.S. relations with Ireland have long been based on common ancestral ties and shared values.[1] Besides regular dialogue on political and economic issues, the U.S. and Irish governments have official exchanges in areas such as medical research and education. Ireland pursues a policy of neutrality through non-alignment and is consequently not a member of NATO,[2] although it does participate in Partnership for Peace. However, on many occasions Ireland has provided tacit support to the United States and its allies.

According to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report, 67% of Irish people approve of U.S. leadership, the fourth-highest rating for any surveyed country in Europe.[3]

History

Pre-Irish independence

In 1800 under the Acts of Union 1800, Ireland was politically unified with Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. All major diplomatic decisions regarding Ireland were made in London. From this time until 1922, when twenty-six of thirty-two counties of Ireland seceded to form the Irish Free State (later becoming the Republic of Ireland), the United States' formal diplomatic affairs with Ireland were carried out through London.

Immigration

The Irish exerted their own influence inside the United States, particularly through Democratic Party politics. From 1820 to 1860, 2 million Irish arrived in the United States, 75% of these after the Great Irish Famine (or The Great Hunger, Irish: An Gorta Mór) of 1845–1852, struck.[4] Most of them joined fast-growing Irish shantytowns in American cities. The famine hurt Irish men and women alike, especially those poorest or without land.[5] It altered the family structures of Ireland because fewer people could afford to marry and raise children, causing many to adopt a single lifestyle. Consequently, many Irish citizens were less bound to family obligations and could more easily migrate to the United States in the following decade.[6]

Fenians

After the American Civil War, authorities in the U.S. who were resentful of Britain's role in the war looked the other way as Irish "Fenians" plotted and even attempted an invasion of Canada.[7] The Fenians proved a failure but Irish American politicians, a growing power in the Democratic Party demanded more independence for Ireland and made anti-British rhetoric—called "twisting the lion's tail"—a staple of election campaign appeals to the Irish vote.[8]

de Valera

Éamon de Valera, a prominent figure in the Easter Rising and the Irish War of Independence, was himself born in New York City in 1882. His American citizenship spared him from execution for his role in the Easter Rising.[9][10]

De Valera went on to be named President of Dáil Éireann, and in May 1919 he visited the United States in this role. The mission had three objectives: to ask for official recognition of the Irish Republic, to float a loan to finance the work of the Government (and by extension, the Irish Republican Army), and to secure the support of the American people for the republic. His visit lasted from June 1919 to December 1920 and had mixed success. One negative outcome was the splitting of the Irish-American organisations into pro- and anti-de Valera factions.[11] De Valera managed to raise $5,500,000 from American supporters, an amount that far exceeded the hopes of the Dáil.[12] Of this, $500,000 was devoted to the American presidential campaign in 1920 which helped him gain wider public support there.[13] In 1921 it was said that $1,466,000 had already been spent, and it is unclear when the net balance arrived in Ireland.[14] Recognition was not forthcoming in the international sphere. He also had difficulties with various Irish-American leaders, such as John Devoy and Judge Daniel F. Cohalan, who resented the dominant position he established, preferring to retain their control over Irish affairs in the United States.

Post-Irish independence

The Irish War of Independence ultimately ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in the partition of Ireland into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, the latter of which opted to remain a part of the United Kingdom. The Irish Free State quickly fell into the Irish Civil War between Pro-Treaty Forces who supported independence via partition and Anti-Treaty Forces who opposed partition and wanted independence for the entire island of Ireland. Pro-Treaty Forces won the Irish Civil War in 1923, and the following year in 1924 the United States recognized the Irish Free State and establish diplomatic relations with it.[15] The Irish Free State was succeeded by the Republic of Ireland in 1937, and it is this country that the United States now refers to as "Ireland" when conducting diplomatic relations.

Ireland was officially neutral during World War II, but declared an official state of emergency on 2 September 1939 and the Army was mobilised. As the Emergency progressed, more and newer equipment was purchased for the rapidly expanding force from Britain and the United States as well as some manufactured at home. For the duration of the Emergency, Ireland, while formally neutral, tacitly supported the Allies in several ways.[16] German military personnel were interned in the Curragh along with the belligerent powers' servicemen, whereas Allied airmen and sailors who crashed in Ireland were very often repatriated, usually by secretly moving them across the border to Northern Ireland.[16] G2, the Army's intelligence section, played a vital role in the detection and arrest of German spies, such as Hermann Görtz. During the Cold War, Irish military policy, while ostensibly neutral, was biased towards NATO.[17] During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Seán Lemass authorised the search of Cuban and Czechoslovak aircraft passing through Shannon and passed the information to the CIA.[18]

U.S. foreign direct investment in Ireland has been particularly important to the growth and modernization of Irish industry since 1980, providing new technology, export capabilities, and employment opportunities. During the 1990s, Ireland experienced a period of rapid economic growth referred to as the Celtic Tiger. While Ireland's historical economic ties to the UK had often been the subject of criticism, Peader Kirby argued that the new ties to the US economy were met with a "satisfied silence".[19] Nevertheless, voices on the political left have decried the "closer to Boston than Berlin" philosophy of the Fianna Fail-Progressive Democrat government.[20] Growing wealth was blamed for rising crime levels among youths, particularly alcohol-related violence resulting from increased spending power. However, it was also accompanied by rapidly increased life expectancy and very high quality of life ratings; the country ranked first in The Economist's 2005 quality of life index.[21]

The Troubles caused a strain in the Special Relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States. In February 1994, British Prime Minister John Major refused to answer US President Bill Clinton's telephone calls for days over his decision to grant Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams a visa to visit the United States.[22] Adams was listed as a terrorist by London.[23] The US State Department, the CIA, the US Justice Department and the FBI all opposed the move on the grounds that it made the United States look 'soft on terrorism' and 'could do irreparable damage to the special relationship'.[24] Under pressure from Congress, the president hoped the visit would encourage the IRA to renounce violence.[25] While Adams offered nothing new, and violence escalated within weeks,[26] the president later claimed vindication after the IRA ceasefire of August 1994.[27] To the disappointment of the prime minister, Clinton lifted the ban on official contacts and received Adams at the White House on St. Patrick's Day 1995, despite the fact the paramilitaries had not agreed to disarm.[23] The US also involved itself as an intermediary during the Northern Ireland peace process, including, in 1995, US Senator George Mitchell being appointed to lead an international body to provide an independent assessment of the decommissioning issue, and President Clinton speaking in favor of the "peace process" to a huge rally at Belfast's City Hall where he called terrorists "yesterday's men". Mitchell announced the reaching of the Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998 stating, "I am pleased to announce that the two governments and the political parties in Northern Ireland have reached agreement," and it emerged later that President Clinton had made a number of telephone calls to party leaders to encourage them to reach this agreement.

Ireland's air facilities were used by the United States military for the delivery of military personnel involved in the 2003 invasion of Iraq through Shannon Airport. The airport had previously been used for the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, as well as the First Gulf War.[28] The government of Republic of Ireland has come under internal and external pressure to inspect airplanes at Shannon Airport to investigate whether or not they contain extraordinary rendition captives.[29][30] Police at Shannon said that they had received political instruction not to approach, search or otherwise interfere with US aircraft suspected of being involved in extraordinary rendition flights. Irish Justice Minister Dermot Ahern sought permission from the US for random inspection of US flights, to provide political "cover" to him in case rendition flights were revealed to have used Shannon; he believed at least three flights had done so.[31] Ireland has been censured by the European Parliament for its role in facilitating extraordinary rendition and taking insufficient or no measures to uphold its obligations under the UN CAT.[32]

With Ireland's membership in the European Union, the discussion of EU trade and economic policies, as well as other aspects of EU policy, is also a key element in the U.S.-Irish relationship. In recent years, Ireland has attempted to act as a diplomatic bridge between the United States and the European Union. During its 2004 Presidency of the Council of the European Union, Ireland worked to strengthen U.S.-EU ties that had been strained by the Iraq War, and former Irish Taoiseach John Bruton was named EU Ambassador to the United States.

In May 2011, U.S. President Barack Obama visited Ireland.[33]

Economic ties

Subsidiaries of US multinationals have located in Ireland due to low taxation. Ireland is the world's most profitable country for US corporations, according to analysis by US tax journal Tax Notes.[34] In 2013, Ireland was named the "best country for business" by Forbes.[35]

The United States is Ireland's largest export partner and second-largest import partner (after the United Kingdom), accounting for 23.2% of exports and 14.1% of imports in 2010.[36] It is also Ireland's largest trading partner outside of the European Union. In 2010, trade between Ireland and the United States was worth around $36.25 billion. U.S. exports to Ireland were valued at $7.85 billion while Irish exports to the U.S. were worth some $28.4 billion, with Ireland having a trade surplus of $20.5 billion over the U.S.[37] The range of U.S. products imported to Ireland includes electrical components, computers and peripherals, pharmaceuticals, electrical equipment, and livestock feed. Exports to the United States include alcoholic beverages, chemicals and related products, electronic data processing equipment, electrical machinery, textiles and clothing, and glassware.

The major U.S. investments in Ireland to date have included multibillion-dollar investments by Intel, Dell, Apple Inc, Microsoft, IBM, Wyeth, Quintiles, Google, EMC and Abbott Laboratories. Currently, there are more than 600 U.S. subsidiaries operating in Ireland, employing in excess of 100,000 people and spanning activities from manufacturing of high-tech electronics, computer products, medical supplies, and pharmaceuticals to retailing, banking and finance, and other services. Many U.S. businesses find Ireland an attractive location to manufacture for the EU market, since as a member of the EU it has tariff free access to the European Common Market. Government policies are generally formulated to facilitate trade and inward direct investment. The availability of an educated, well-trained, English-speaking work force and relatively moderate wage costs have been important factors. Ireland offers good long-term growth prospects for U.S. companies under an innovative financial incentive programme, including capital grants and favourable tax treatment, such as a low corporation income tax rate for manufacturing firms and certain financial services firms. Irish firms are now beginning to provide a lot of employment in the U.S., for example indigenous Irish companies, particularly in the high tech sector have provided in excess of 80,000 jobs to date for American citizens.

Cultural ties

Irish immigration to the USA has played a large role in the culture of the United States. About 33.3 million Americans—10.5% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2013 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.[38] Irish Americans have made many contributions to American culture and sport. Halloween is thought to have evolved from the ancient Celtic/Gaelic festival of Samhain, which was introduced in the American colonies by Irish settlers.

A number of the presidents of the United States have Irish origins.[39] The extent of Irish heritage varies. For example, Chester Arthur's father and both of Andrew Jackson's parents were Irish-born, while George W. Bush has a rather distant Irish ancestry. Ronald Reagan's father was of Irish ancestry,[40] while his mother also had some Irish ancestors. John F. Kennedy had Irish lineage on both sides. Within this group, only Kennedy was raised as a practicing Roman Catholic. Current President Barack Obama's Irish heritage originates from his Kansas-born mother, Ann Dunham, whose ancestry is Irish and English.[41] His Vice President Joe Biden is also an Irish-American.

Emigration, long a vital element in the U.S.–Irish relationship, declined significantly with Ireland's economic boom in the 1990s. For the first time in its modern history, Ireland experienced high levels of inward migration, a phenomenon with political, economic, and social consequences. However, Irish citizens do continue the common practice of taking temporary residence overseas for work or study, mainly in the US, UK, Australia and elsewhere in Europe, before returning to establish careers in Ireland. The US J-1 visa program, for example, remains a popular means for Irish youths to work temporarily in the United States.[42]

Embassy

The Embassy of the United States is in Dublin.

Principal U.S. Officials include:

- Ambassador – Kevin O'Malley

- Deputy Chief of Mission – Robert Faucher

- Management Section Chief – Douglas Brown

- Senior Commercial Officer – Mitch Auerbach

- Consular Section Chief – Daniel Toma

- Defense Attaché – Col. Paul Flynn

- Political/Economic Section Chief – Ted Pierce

- Regional Security Officer – Terry Cobble

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection Port Director – Juan Soltero

- Public Affairs Officer – Sheila Paskman

See also

- United States Ambassador to Ireland

- Embassy of the United States in Dublin

- Deerfield Residence (United States Ambassador's Official Residence in Ireland)

- Ireland–NATO relations

- Irish Americans

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Foreign relations of the Republic of Ireland

- Irish diaspora

References

- ↑ Ireland US Department of State Retrieved 2011-02-20

- ↑ "NATO - Member countries". NATO. NATO. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Global Leadership Project Report - 2012 Gallup

- ↑ "Irish-Catholic Immigration to America". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ Diner, Hasia R. (1983). Erin's Daughters in America: Irish Immigrant Women in the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–9, 31.

- ↑ Diner, Hasia R. Erin's Daughters. pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Niall Whelehan, The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867–1900 (Cambridge, 2012)

- ↑ Michael J. Hogan (2000). Paths to Power: The Historiography of American Foreign Relations to 1941. Cambridge U.P. p. 76.

- ↑ McElrath, Karen (2000). Unsafe haven: the United States, the IRA, and political prisoners. Pluto Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7453-1317-7. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Ward, Alan J. (1969). Ireland and Anglo-American relations, 1899-1921. 1969, Part 1. London School of Economics and Political Science, Weidenfeld & Nicolson,. p. 24. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Jordan, Anthony J. Eamon de Valera 1882–1975, pp. 63–70.

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 2 – Vote of thanks to the people of America". Houses of the Oireachtas. 17 August 1921. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 1 – Ministerial Motions. – Presidential election campaign in USA". Houses of the Oireachtas. 29 June 1920. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 1 – Debates on Reports. – Finance". Houses of the Oireachtas. 10 May 1921. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ "Ireland - Countries - Office of the Historian". Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- 1 2 Fanning, R., 1983, Independent Ireland, Dublin: Helicon, Ltd.., pp 124–25

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael (8 October 2014). "Ireland's Role in Post-War Transatlantic Aviation and Its Implications for the Defence of the North Atlantic Area". Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ Irish Times, 28 December 2007 p. 1.

- ↑ Paul Keenan. Book review of Peader Kirby's The Celtic Tiger In Distress. Accessed 4 November 2006.

- ↑ Creaton, Siobhan (24 February 2011). "FF-PD policy to blame for economic ills, claims report". Irish Independent.

- ↑ "The Economist Intelligence Unit’s quality-of-life index" (PDF). The Economist.

- ↑ Rusbridger, Alan (21 June 2004). "'Mandela helped me survive Monicagate, Arafat could not make the leap to peace – and for days John Major wouldn't take my calls'". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- 1 2 Villa, ‘The Reagan-Thatcher "special relationship" has not weathered the years’.

- ↑ Alec Russell, 'Major's fury over US visa for Adams', Daily Telegraph (23 June 2004), p. 9.

- ↑ Joseph O'Grady, 'An Irish Policy Born in the U.S.A.: Clinton's Break with the Past', Foreign Affairs, Vol. 75, No. 3 (May/June 1996), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ O'Grady, 'An Irish Policy Born in the U.S.A.', p. 5.

- ↑ Russell, ‘Major's fury’, Daily Telegraph, p. 9.

- ↑ "Private Members' Business. – Foreign Conflicts: Motion (Resumed)". Government of Ireland. 30 January 2003. Retrieved 10 October 2007. – Tony Gregory speaking in Dáil Éireann

- ↑ Grey, Stephen (14 November 2004). "US ‘torture flights’ stopped at Shannon". The Times (London). Retrieved 8 September 2005.

- ↑ "Investigations into CIA 'torture flights'". Village. 25 November 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ↑ Kelley, Dara,WikiLeaks reveals Justice Minister's Dermot Ahern's rendition fears Irish Central, 18 December 2010.

- ↑ EU to censure Ahern over rendition role, The Irish Times, 24 January 2007.

- ↑ Obama in Ireland: president searches for 'missing apostrophe' The Telegraph, 23 May 2011

- ↑ "Ireland top location for US Multinational Profits". Finfacts.ie. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- ↑ Gleeson, Collin (5 December 2013). "Forbes names Ireland as 'best country for business'". Irish Times (irishtimes.com). Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ↑ "CSO – Main Trading Partners 2010". Cso.ie. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ↑ "Country Trade Profile". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States (DP02): 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Irish-American History Month, 1995". irishamericanheritage.com. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ William Borders (September 6, 1981). "Village in Tipperary is Cashing In on Ronald Reagan's Roots". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Presidents, Barack Obama". American Heritage.com. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ↑ http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3180.htm

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State (Background Notes).

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State (Background Notes).

Further reading

- Brown, Thomas N. "The Origins and Character of Irish-American Nationalism." Review of Politics (1956) 18#03 pp: 327-358.

- Cooper, James, "'A Log-Rolling, Irish-American Politician, Out to Raise Votes in the United States': Tip O'Neill and the Irish Dimension of Anglo-American Relations, 1977-1986," Congress and the Presidency, (2015) 42#1 pp: 1-27.

- Cronin, Seán. Washington's Irish Policy 1916-1986: Independence, Partition, Neutrality (Dublin: Anvil Books, 1987)

- Davis, Troy D. Dublin's American Policy: Irish-American Diplomatic Relations, 1945-1952 (Catholic University of Amer Press, 1998)

- Finnegan, Richard B. "Irish–American Relations." in by William J. Crotty and David Schmitt, eds. Ireland on the World Stage (2002): 95-110.

- Geiger, Till, and Michael Kennedy, eds. Ireland, Europe and the Marshall Plan (Four Courts PressLtd, 2004)

- Guelke, Adrian. "The United States, Irish Americans and the Northern Ireland Peace Process," International Affairs (1996) 72#3 pp: 521-36.

- MacGinty, Roger. "American influences on the Northern Ireland peace process." Journal of Conflict Studies 17#2 (1997). online

- Sewell, Mike J. "Rebels or Revolutionaries? Irish-American Nationalism and American Diplomacy, 1865–1885." The Historical Journal (1986) 29#3 pp: 723-733.

- Sim, David. A Union Forever: The Irish Question and U.S. Foreign Relations in the Victorian Age (2013) excerpt

- Tansill, Charles. America and the Fight for Irish Freedom 1866-1922 (1957) excerpt

- Ward, Alan J. "America and the Irish Problem 1899-1921." Irish Historical Studies (1968): 64-90. in JSTOR

- Wilson, Andrew J. Irish America and the Ulster Conflict, 1968-1995 (Catholic University of Amer Press, 1995)

External links

![]() Media related to Ireland – United States relations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ireland – United States relations at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)