Invasion of Iceland

| Invasion of Iceland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

Initial British aims were to destroy all landing grounds (blue) and secure key harbours (red). Due to transportation problems it was more than a week before troops arrived in the north of the country. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

British: 746 Royal Marines 4 warships 25,000 British and Canadian Army American: 3,908 U.S. Marines Task Force 19: 25-warship convoy 40,000 U.S. Army and U.S. Navy | 60 officers, plus policemen and other forces | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed (suicide en route) | 1 killed (12 year old shot following the occupation) | ||||||

| A small number of German citizens were arrested | |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Iceland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Modern era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iceland portal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The invasion of Iceland, codenamed Operation Fork, was a British military operation conducted by the Royal Navy and Royal Marines during World War II. The invasion began in the early morning of 10 May 1940 with British troops disembarking in Reykjavík, capital of neutral Iceland. Meeting no resistance, the troops moved quickly to disable communication networks, secure strategic locations, and arrest German citizens. Requisitioning local means of transportation, the troops moved to Hvalfjörður, Kaldaðarnes, Sandskeið, and Akranes to secure landing areas against the possibility of a German counterattack. In the following days air defence equipment was deployed in Reykjavík and a detachment of troops was sent to Akureyri.

In the evening of 10 May, the government of Iceland issued a protest, charging that the neutrality of Iceland had been "flagrantly violated" and "its independence infringed" and noting that compensation would be expected for all damage done. The British promised compensation, favourable business agreements, non-interference in Icelandic affairs, and the withdrawal of all forces at the end of the war. Resigning themselves to the situation, the Icelandic authorities provided the invasion force with de facto cooperation, though formally maintaining a policy of neutrality.

The invasion force consisted of 746 Royal Marines, ill-equipped and only partially trained.[1] Although it succeeded in its mission, it was manifestly insufficient to defend an island of 103,000 square kilometres (40,000 sq mi). On 17 May 4,000 troops of the British Army arrived in Iceland to relieve the marines. This force was subsequently augmented to a final force consisting of 25,000 troops of the British and Canadian armies.[2] A year later, American troops of the U.S. Marines' 1st Provisional Marine Brigade under the command of Brigadier General John Marston were tasked with relieving the British, although the country was still officially a non-belligerent. They were augmented and ultimately relieved by U.S. Army troops, who remained there for the duration of the war.

Background

In 1918, after a long period of Danish rule, Iceland had become an independent state in personal union with Denmark and with common handling of foreign affairs.[3] The newly born Kingdom of Iceland declared itself a neutral country without a defence force.[3] The treaty of union allowed for a revision to begin in 1941 and for unilateral termination three years after that, if no agreement was reached.[3] By 1928, all Icelandic political parties were in agreement that the union treaty would be terminated as soon as possible.[4]

On 9 April 1940, German forces launched Operation Weserübung, invading both Norway and Denmark. Denmark was subdued within a day and occupied. On the same day, the British government sent a message to the Icelandic government, stating that Britain was willing to assist Iceland in maintaining her independence but would require facilities in Iceland to do so. Iceland was invited to join Britain in the war "as a belligerent and an ally." The Icelandic government rejected the offer.[6]

On the next day, 10 April, the Icelandic parliament, the Alþingi (Althing in English), declared Danish King Christian X unable to perform his constitutional duties and assigned them to the government of Iceland, along with all other responsibilities previously carried out by Denmark on behalf of Iceland.[7]

On 12 April, in Operation Valentine, the British took over the Faroe Islands.

Following the German invasion of Denmark and Norway, the British government became increasingly concerned that Germany would soon try to establish a military presence in Iceland. They felt that this would constitute an intolerable threat to British control of the North Atlantic. Just as importantly, the British were eager to obtain bases in Iceland for themselves to strengthen their Northern Patrol.[8]

Planning

| “ | Home 8. Dined and worked. Planning conquest of Iceland for next week. Shall probably be too late! Saw several broods of ducklings. | ” |

| — Alexander Cadogan, British Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, diary entry for 4 May 1940.[9] | ||

As the military situation in Norway deteriorated, the Admiralty came to the conclusion that Britain could no longer do without bases in Iceland. On 6 May, Winston Churchill presented the case to the War Cabinet. Churchill maintained that if further negotiations with the Icelandic government were attempted, the Germans might learn of them and act first. A surer and more effective solution was to land troops unannounced and present the Icelandic government with a fait accompli. The War Cabinet approved the plan.[10]

The expedition was organized hastily and haphazardly.[11] Much of the operational planning was conducted en route. The force was supplied with few maps, most of poor quality, with one of them having been drawn from memory. No one in the expedition was fully fluent in the Icelandic language.[12]

The British planned to land all of their forces at Reykjavík. There, they would overcome any resistance and defeat local Germans. To guard against a German counterattack by sea, they would secure the harbour and send troops by land to nearby Hvalfjörður. The British were also worried that the Germans might airlift troops, as they had done with great success in their Norwegian Campaign. To guard against this, troops would drive east to the landing grounds at Sandskeið and Kaldaðarnes. Lastly, troops would be sent by land to the harbour at Akureyri and the landing ground at Melgerði in the north of the country.[13]

The Naval Intelligence Division (NID) expected resistance from three possible sources. Local Germans, who were thought to have some arms, could be expected to resist or even attempt some sort of coup. In addition, a German invasion force might already be under way or launched immediately following the British landings. The NID also expected resistance from the Reykjavík police, consisting of some 70 men under arms. If by chance a Danish patrol vessel were present in Reykjavík, the Danish sailors might assist the defenders.[14]

Operation Fork

Force Sturges

On 3 May 1940, the 2nd Royal Marine Battalion in Bisley, Surrey received orders from London to be ready to move at two hours' notice for an unknown destination. The battalion had only been activated the month before. Though there was a nucleus of active service officers, the troops were new recruits and only partially trained.[1] There was a shortage of weapons, whih consisted only of rifles, pistols, and bayonets, while 50 of the marines had only just received their rifles and had not had a chance to fire them. On 4 May, the battalion received some modest additional equipment in the form of Bren light machine guns, anti-tank guns, and 2-inch mortars. With no time to spare, zeroing of the weapons and initial familiarisation firing would have to be conducted at sea.[15]

Supporting arms provided to the force consisted of two 3.7 inch mountain howitzers, four QF 2 pounder naval guns, and two 4-inch coastal defence guns.[15] The guns were manned by troops from the artillery divisions of the Navy and the marines, none of whom had ever fired them.[15] They lacked searchlights, communication equipment, and gun directors.[16]

Colonel Robert Sturges was assigned to command the force. Aged 49, he was a highly regarded veteran of World War I, having fought in the Battle of Gallipoli and the Battle of Jutland.[17] He was accompanied by a small intelligence detachment under Major Humphrey Quill and a diplomatic mission headed by Charles Howard Smith.[1] Excluding those, the invasion force consisted of 746 troops.[18]

Journey to Iceland

.jpg)

On 6 May, Force Sturges boarded trains for Greenock on the Clyde. In order to avoid drawing attention to itself, the force was divided into two different trains for the journey,[19] but due to delays in rail travel, the troops arrived at the railway station in Greenock around the same time, losing the small degree of anonymity desired.[19] Additionally, security had been compromised by a dispatch in the clear and by the time the troops arrived in Greenock, everyone knew that the destination was Iceland.[1]

In the morning of 7 May, the force headed to the harbour in Greenock, where they found the cruisers Berwick and Glasgow, intended to take them to Iceland. Boarding commenced, but was fraught with problems and delays. Departure was delayed until 8 May, and even then a large amount of equipment and supplies had to be left on the piers.[20]

At 04:00 on 8 May, the cruisers departed for Iceland. They were accompanied by an anti-submarine escort consisting of the destroyers Fearless and Fortune. The cruisers were not designed to transport a force of the size assigned to them, and conditions were cramped.[12] Despite reasonably good weather, many of the marines developed severe seasickness. The voyage was used as planned for calibration and familiarization with the newly acquired weapons.[21]

One of the newly recruited marines committed suicide en route.[22] The voyage was otherwise uneventful.[16]

In May 1940 we transported Royal Marines to Iceland and the island was occupied on the 10th May to prevent the occupation by a German force. A number of German civilians and technicians were made prisoners and transported back to the United Kingdom. Very rough seas were encountered on passage to Iceland and the majority of the marines cluttered gangways and mess-decks throughout the ship, prostrate with seasickness. One unfortunate marine committed suicide.— Stan Foreman, petty officer of HMS Berwick[23]

Surprise is lost

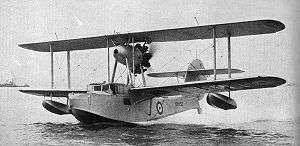

At 01:47, Icelandic time, on 10 May, HMS Berwick used its catapult to launch a Supermarine Walrus reconnaissance plane.[25] The principal aim of the flight was to scout the vicinity of Reykjavík for enemy submarines, which the Naval Intelligence Division had convinced itself were operating out of Icelandic harbours.[25] The Walrus was given orders not to fly over Reykjavík but – either accidentally or as the result of a miscommunication – it flew several circles over the town, making considerable noise.[26] At this time, Iceland possessed no aeroplanes of its own, so this unusual event woke up and alerted a number of people.[27] Icelandic Prime Minister Hermann Jónasson was alerted to the plane,[28] as were the Icelandic Police. The acting chief of police, Einar Arnalds, surmised that it most likely originated from a British warship bringing the expected new ambassador.[28] This was correct, though it was not the whole story.

Werner Gerlach, the German consul, was also alerted to the plane. Suspecting what was about to happen, he drove down to the harbour with a German associate.[29] With the use of binoculars, he confirmed his fears and then hurried back.[30] At home, he arranged for the burning of his documents and tried unsuccessfully to reach the Icelandic foreign minister by telephone.[31]

Down at the harbour

At 03:40, an Icelandic policeman saw a small fleet of warships approaching the harbour, but could not discern their nationality. He notified his superior, who notified Einar Arnalds, the acting chief of police.[32] The laws of neutrality to which Iceland had committed forbade more than three warships from a belligerent nation from making use of a neutral harbour at the same time. Any aeroplanes from such ships were forbidden from flying over neutral territorial waters.[28] Seeing that the approaching fleet was about to violate Icelandic neutrality in two ways, Arnalds set out to investigate.[28] Down at the harbour, he viewed the ships for himself and decided they were probably British. He contacted the foreign ministry, which confirmed that he should go out to the fleet and announce to its commander that he was in violation of Icelandic neutrality.[33] Customs officers were ordered to prepare a boat.[33]

Meanwhile, marines on Berwick were being ordered aboard Fearless, which would take them to the harbour. The seasickness and inexperience of the troops were causing delays and the officers were becoming frustrated.[34] Just before five o'clock in the morning, Fearless, loaded with around 400 marines, set out for the harbour.[35] A small crowd had assembled, including several policemen still waiting for the customs boat. The British consul had received advance notice of the invasion and was waiting with his associates to assist the troops when they arrived. Uncomfortable with the crowd, Consul Shepherd turned to the Icelandic police. "Would you mind ... getting the crowd to stand back a bit, so that the soldiers can get off the destroyer?" he asked. "Certainly," came the reply.[35]

The Fearless started disembarking immediately once it docked.[36] Arnalds asked to speak with the captain of the destroyer, but was refused.[37] He then hastened to report to the Prime Minister, who ordered him not to interfere with the British troops and to try to prevent conflicts between them and Icelanders.[37]

Down at the harbour, some of the locals protested against the arrival of the British. One Icelander snatched a rifle from a marine and stuffed a cigarette in it. He then threw it back to the marine and told him to be careful with it. An officer arrived to scold the marine.[38]

Operations in Reykjavík

The British forces began their operations in Reykjavík by posting a guard at the post office and attaching a flier to the door.[39] The flier explained in broken Icelandic that British forces were occupying the city and asked for cooperation in dealing with local Germans.[40] The offices of Síminn (telecommunication service), RÚV (broadcasting service), and the Meteorological Office were quickly put under British control to prevent news of the invasion from reaching Berlin.[41]

Meanwhile, high priority was assigned to the capture of the German consulate. Arriving at the consulate, the British troops were relieved to find no sign of resistance and simply knocked on the door. Consul Gerlach opened, protested against the invasion, and reminded the British that Iceland was a neutral country. He was reminded, in turn, that Denmark had also been a neutral country.[42] The British discovered a fire upstairs in the building and found a pile of documents burning in the consul's bathtub. They extinguished the fire and salvaged a substantial number of records.[43]

The British had also expected resistance from the crew of Bahia Blanca, a German freighter which had hit an iceberg in the Denmark Strait and whose 62-man crew had been rescued by an Icelandic trawler. The Naval Intelligence Division believed the Germans were actually reserve crews for the German submarines they thought were operating out of Iceland.[44] The unarmed Germans were captured without incident.[45]

United States occupation force

Britain needed their troops elsewhere, and in July 1941, passed responsibility for Iceland to the United States under a US-Icelandic defence agreement. President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the American occupation of Iceland on 16 June 1941. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade of 194 officers and 3,714 men from San Diego under the command of Brigadier General John Marston sailed from Charleston, South Carolina on 22 June to assemble as Task Force 19 (TF 19) at Argentia, Newfoundland:[46]

Task Force 19

- USS Heywood

- USS Fuller

- USS William P. Biddle

- USS Orizaba

- USS Arcturus

- USS Hamul

- USS Salamonie

- USS Cherokee

- Escort

- Screen

Task Force 19 (TF 19) sailed from Argentia on 1 July. On 7 July, Britain persuaded the Althing to approve an American occupation force, and TF 19 anchored off Reykjavík that evening. The United States Marine Corps commenced landing on 8 July, and disembarkation was completed on 12 July. On 6 August, the United States Navy established an air base at Reykjavík with the arrival of Patrol Squadron VP-73 PBY Catalinas and VP-74 PBM Mariners. United States Army personnel began arriving in Iceland in August, and the Marines had been transferred to the Pacific by March 1942.[46] During the period 1942-1943, roughly 50,000 US military personnel were stationed on the island, outnumbering adult Icelandic men (at the time, Iceland had a total population of about 130,000).[47] The US Navy remained at Naval Air Station Keflavik until 2006.

Outcome

Although the British action was to forestall any risk of a German invasion, none had been planned. There is only evidence of a German interest in seizing Iceland. In a postwar interview with an American, Walter Warlimont claimed, "Hitler definitely was interested in occupying Iceland prior to [British] occupation. In the first place, he wanted to prevent "anyone else" from coming there; and, in the second place, he also wanted to use Iceland as an air base for the protection of our submarines operating in that area".[48]

However, after the British invasion, the Germans drew up a report to examine the feasibility of seizing Iceland, Operation Ikarus, but this was abandoned. The report found that while an invasion could be successful, maintaining supply lines would be too costly and the benefits of holding Iceland would not outweigh the costs (there was, for instance, insufficient infrastructure for aircraft in Iceland).[49]

See also

- Ástandið

- British occupation of the Faroe Islands

- Expansion operations and planning of the Axis Powers

- Battle of the Atlantic

- Iceland in the Cold War

- History of Iceland

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Bittner 41.

- ↑ http://www.history.army.mil/books/70-7_03.htm

- 1 2 3 Gunnar Karlsson:283.

- ↑ Gunnar Karlsson:319.

- ↑ "Iceland: Nobody's Baby". Time. 22 April 1940.

- ↑ Bittner 34.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:272.

- ↑ Bittner 33-4.

- ↑ Cadogan 276.

- ↑ Bittner 38.

- ↑ Bittner 40.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1995:363.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:353.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:354, Bittner 36.

- 1 2 3 Bittner 42, Þór Whitehead 1995:352.

- 1 2 Bittner 42.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:352.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:305. Some older sources say 815 but this is inaccurate.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1995:361.

- ↑ Bittner 42, Þór Whitehead 1995:362.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:364.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:374-5, Miller 88.

- ↑ "WW2 People's War: Stan Foreman's War Years 1939–1945". BBC. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ↑ Bittner 76.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1995:379.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:380, 1999:15.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:15.

- 1 2 3 4 Þór Whitehead 1999:17.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:380–384.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:11.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:30–32.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:15–17.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1999:22–23.

- ↑ Miller 88, Þór Whitehead 1999:10.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1999:24–25.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:25.

- 1 2 Þór Whitehead 1999:28.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:27.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:33.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:34.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:35.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:39.

- ↑ Bittner:43.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1995:356.

- ↑ Þór Whitehead 1999:47.

- 1 2 Morison, Samuel Eliot (1975). The Battle of the Atlantic September 1939 – May 1943. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 74–79.

- ↑ Ingimundarson, Valur (1996). Í eldlínu kalda stríðsins. p. 22. ISBN 9979-2-1203-9.

- ↑ Whitehead, Þór (2006). "Hlutleysi Íslands á hverfandi hveli". Saga: 22.

- ↑ "Hverjar voru áætlanir Þjóðverja um að ráðast inn í Ísland í seinni heimsstyrjöldinni?". Retrieved 2015-09-24.

References

- Bittner, Donald F. (1983). The Lion and the White Falcon: Britain and Iceland in the World War II Era. Archon Books, Hamden. ISBN 0-208-01956-1.

- Cadogan, Alexander George Montagu, Sir (1971). The diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan, O.M., 1938–1945, Dilks, David (Ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-93737-1.

- Gunnar Karlsson (2000). Iceland's 1100 Years: History of a Marginal Society. Hurst, London. ISBN 1-85065-420-4.

- Gunnar M. Magnúss (1947). Virkið í norðri: Hernám Íslands: I. bindi. Ísafoldarprentsmiðja, Reykjavík.

- Miller, James (2003). The North Atlantic Front: Orkney, Shetland, Faroe and Iceland at War. Birlinn, Edinburgh. ISBN 1-84341-011-7.

- Þór Whitehead (1999). Bretarnir koma: Ísland í síðari heimsstyrjöld. Vaka-Helgafell, Reykjavík. ISBN 9979-2-1435-X.

- Þór Whitehead (1995). Milli vonar og ótta: Ísland í síðari heimsstyrjöld. Vaka-Helgafell, Reykjavík. ISBN 9979-2-0317-X.

Further reading

- Fairchild, Byron (2000 (reissue from 1960)). "Decision to Land United States Forces in Iceland, 1941". In Kent Roberts Greenfield. Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

External links

- Address by Markús Örn Antonsson (Icelandic Ambassador to Canada), 21 October 2006

- "Franklin D. Roosevelt's message to Congress on the US occupation of Iceland" US State Department (7 July 1941)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||