Constructive set theory

Constructive set theory is an approach to mathematical constructivism following the program of axiomatic set theory. That is, it uses the usual first-order language of classical set theory, and although of course the logic is constructive, there is no explicit use of constructive types. Rather, there are just sets, thus it can look very much like classical mathematics done on the most common foundations, namely the Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms (ZFC).

Intuitionistic Zermelo–Fraenkel

In 1973, John Myhill proposed a system of set theory based on intuitionistic logic[1] taking the most common foundation, ZFC, and throwing away the axiom of choice (AC) and the law of the excluded middle (LEM), leaving everything else as is. However, different forms of some of the ZFC axioms which are equivalent in the classical setting are inequivalent in the constructive setting, and some forms imply LEM.

The system, which has come to be known as IZF, or Intuitionistic Zermelo–Fraenkel (ZF refers to ZFC without the axiom of choice), has the usual axioms of extensionality, pairing, union, infinity, separation and power set. The axiom of regularity is stated in the form of an axiom schema of set induction. Also, while Myhill used the axiom schema of replacement in his system, IZF usually stands for the version with collection

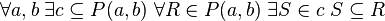

While the axiom of replacement requires the relation φ to be a function over the set A (that is, for every x in A there is associated exactly one y), the axiom of collection does not: it merely requires there be associated at least one y, and it asserts the existence of a set which collects at least one such y for each such x. The axiom of regularity as it is normally stated implies LEM, whereas the form of set induction does not. The formal statements of these two schemata are:

![\forall A \; ([\forall x \in A \; \exists y \; \phi(x,y)] \to \exists B \; \forall x \in A \; \exists y \in B \; \phi(x,y))](../I/m/fbd2d871ddfccda5ae40dcda5924a156.png)

![[\forall y \; ([\forall x \in y \; \phi(x)] \to \phi(y))] \to \forall y \; \phi(y)](../I/m/3c0b315a525e87c8d30c53fae1fe0025.png)

Adding LEM back to IZF results in ZF, as LEM makes collection equivalent to replacement and set induction equivalent to regularity. Even without LEM, IZF's proof-theoretical power equals that of ZF.

Predicativity

While IZF is based on constructive rather than classical logic, it is considered impredicative. It allows formation of sets using the axiom of separation with any proposition, including ones which contain quantifiers which are not bounded. Thus new sets can be formed in terms of the universe of all sets. Additionally the power set axiom implies the existence of a set of truth values. In the presence of LEM, this set exists and has two elements. In the absence of it, the set of truth values is also considered impredicative.

Myhill's constructive set theory

The subject was begun by John Myhill to provide a formal foundation for Errett Bishop's program of constructive mathematics. As he presented it, Myhill's system CST is a constructive first-order logic with three sorts: natural numbers, functions, and sets. The system is:

- Constructive first-order predicate logic with identity, and basic axioms related to the three sorts.

- The usual Peano axioms for natural numbers.

- The usual axiom of extensionality for sets, as well as one for functions, and the usual axiom of union.

- A form of the axiom of infinity asserting that the collection of natural numbers (for which he introduces a constant N) is in fact a set.

- Axioms asserting that the domain and range of a function are both sets. Additionally, an axiom of non-choice asserts the existence of a choice function in cases where the choice is already made. Together these act like the usual replacement axiom in classical set theory.

- The axiom of exponentiation, asserting that for any two sets, there is a third set which contains all (and only) the functions whose domain is the first set, and whose range is the second set. This is a greatly weakened form of the axiom of power set in classical set theory, to which Myhill, among others, objected on the grounds of its impredicativity.

- The axiom of restricted, or predicative, separation, which is a weakened form of the separation axiom in classical set theory, requiring that any quantifications be bounded to another set.

- An axiom of dependent choice, which is much weaker than the usual axiom of choice.

Aczel's constructive Zermelo–Fraenkel

Peter Aczel's constructive Zermelo-Fraenkel,[2] or CZF, is essentially IZF with its impredicative features removed. It strengthens the collection scheme, and then drops the impredicative power set axiom and replaces it with another collection scheme. Finally the separation axiom is restricted, as in Myhill's CST. This theory has a relatively simple interpretation in a version of constructive type theory and has modest proof theoretic strength as well as a fairly direct constructive and predicative justification, while retaining the language of set theory. Adding LEM to this theory also recovers full ZF.

The collection axioms are:

Strong collection schema: This is the constructive replacement for the axiom schema of replacement. It states that if φ is a binary relation between sets which is total over a certain domain set (that is, it has at least one image of every element in the domain), then there exists a set which contains at least one image under φ of every element of the domain, and only images of elements of the domain. Formally, for any formula φ:

Subset collection schema: This is the constructive version of the power set axiom. Formally, for any formula φ:

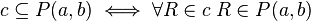

This is equivalent to a single and somewhat clearer axiom of fullness: between any two sets a and b, there is a set c which contains a total subrelation of any total relation between a and b that can be encoded as a set of ordered pairs. Formally:

where the references to P(a,b) are defined by:

and some set-encoding of the ordered pair <x,y> is assumed.

The axiom of fullness implies CST's axiom of exponentiation: given two sets, the collection of all total functions from one to the other is also in fact a set.

The remaining axioms of CZF are: the axioms of extensionality, pairing, union, and infinity are the same as in ZF; and set induction and predicative separation are the same as above.

Interpretability in type theory

In 1977 Aczel showed that CZF can be interpreted in Martin-Löf type theory,[3] (using the now consecrated propositions-as-types approach) providing what is now seen a standard model of CZF in type theory.[4] In 1989 Ingrid Lindström showed that non-well-founded sets obtained by replacing the axiom of foundation in CZF with Aczel's anti-foundation axiom (CZFA) can also be interpreted in Martin-Löf type theory.[5]

Interpretability in category theory

Presheaf models for constructive set theory were introduced by Nicola Gambino in 2004. They are analogous to the Presheaf models for intuitionistic set theory developed by Dana Scott in the 1980s (which remained unpublished).[6][7]

References

- ↑ Myhill, "Some properties of Intuitionistic Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory", Proceedings of the 1971 Cambridge Summer School in Mathematical Logic (Lecture Notes in Mathematics 337) (1973) pp 206-231

- ↑ Peter Aczel and Michael Rathjen, Notes on Constructive Set Theory, Reports Institut Mittag-Leffler, Mathematical Logic - 2000/2001, No. 40

- ↑ Aczel, Peter: 1978. The type theoretic interpretation of constructive set theory. In: A. MacIntyre et al. (eds.), Logic Colloquium '77, Amsterdam: North-Holland, 55–66.

- ↑ Rathjen, M. (2004), "Predicativity, Circularity, and Anti-Foundation", in Link, Godehard, One Hundred Years of Russell ́s Paradox: Mathematics, Logic, Philosophy (PDF), Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-019968-0

- ↑ Lindström, Ingrid: 1989. A construction of non-well-founded sets within Martin-Löf type theory. Journal of Symbolic Logic 54: 57–64.

- ↑ Gambino, N. (2005). "PRESHEAF MODELS FOR CONSTRUCTIVE SET THEORIES". In Laura Crosilla and Peter Schuster. From Sets and Types to Topology and Analysis (PDF). pp. 62–96. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198566519.003.0004. ISBN 9780198566519.

- ↑ Scott, D. S. (1985). Category-theoretic models for Intuitionistic Set Theory. Manuscript slides of a talk given at Carnegie-Mellon University

Further reading

- Troelstra, Anne; van Dalen, Dirk (1988). Constructivism in Mathematics, Vol. 2. Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics. p. 619. ISBN 0-444-70358-6.

- Aczel, P. and Rathjen, M. (2001). Notes on constructive set theory. Technical Report 40, 2000/2001. Mittag-Leffler Institute, Sweden.

External links

- Laura Crosilla, Set Theory: Constructive and Intuitionistic ZF, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Feb 20, 2009

- Benno van den Berg, Constructive set theory – an overview, slides from Heyting dag, Amsterdam, 7 September 2012

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||