IUD with progestogen

| IUD with progestogen | |

|---|---|

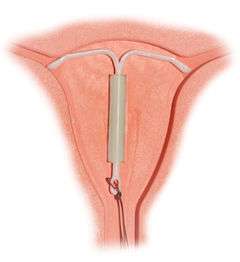

Correctly inserted IUD | |

| Background | |

| Birth control type | Intrauterine |

| First use |

1990 (Mirena—currently available) |

| Failure rates (first year (Mirena)) | |

| Perfect use | 0.2%[1] |

| Typical use | 0.2%[1] |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect |

5 years (Mirena) 3 years (Skyla) |

| Reversibility | 2–6 months |

| User reminders | Check thread position monthly |

| Clinic review | One month after insertion, then annually |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STD protection | No |

| Periods | Causes menstrual irregularity, periods are usually lighter or none at all (amenorrhea) |

| Weight | Potential side effect |

| Benefits | No need to remember to take any daily action |

| Risks |

Ovarian cysts (usually benign) Transient risk PID, Rare risk of uterine perforation, other potential adverse effects |

Intrauterine device (IUD) with progestogen is a hormonal intrauterine device classified as a long-acting reversible contraceptive method. It is one of the most effective forms of birth control.[2] In the United Kingdom (UK), the IUD with progestogen is referred to as an intrauterine system (IUS) or intrauterine contraceptive (IUC). This article will refer to these devices as the hormonal IUD to distinguish from IUD with copper. Mirena is one brand available in the United States and UK.

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the minimum medicines needed in a basic health‐care system.[3]

Medical uses

In addition to birth control, hormonal IUD are used for prevention and treatment of:

- heavy menstrual periods[4]

- Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain[4][5]

- Adenomyosis and dysmenorrhea[4][6]

- Anemia[7]

- In some cases, use of a hormonal IUD may prevent a need for a hysterectomy.[8]

Advantages

- Considered one of the most effective forms of reversible birth control[2]

- Can be used while breastfeeding[9] (see also nursing mothers)

- No preparations needed before sex,[10] though routine checking of the device strings by patient and physician is advised to ensure proper placement remains intact[11]

- Ability to become pregnant returns within 24 months for approximately 90% of users[12]

- May experience lighter periods (some women stop having periods completely, see also amenorrhea)[13]

- Effective for up to three to five years (depending on the IUD)[14]

Disadvantages

- Irregular periods and spotting between periods often occurs after insertion[13]

- Mild to moderate discomfort experienced during insertion procedure, including cramping or backache

- Other potential adverse effects and risks

Effectiveness

After insertion, Mirena is effective for up to five years, although some studies have shown that it may be effective through seven years.[15] Skyla is effective for 3 years.[16]

The hormonal IUD is a long-acting reversible contraceptive, and is considered one of the most effective forms of birth control. The first year failure rate for the hormonal IUD is 0.2% and the five year failure rate is 0.7%.[17] These rates are comparable to tubal sterilization, but unlike sterilization the effects of the hormonal IUD are reversible.

The hormonal IUD is considered to be more effective than other common forms of reversible contraception, such as the birth control pill, because it requires little action by the user after insertion.[2] The effectiveness of other forms of birth control is mitigated (decreased) by the users themselves. If medication regimens for contraception are not followed precisely, the method becomes less effective. IUDs require no daily, weekly, or monthly regimen, so their typical use failure rate is therefore the same as their perfect use failure rate.[2]

In women with bicornuate uterus and in need of contraception, two IUDs are generally applied (one in each horn) due to lack of evidence of efficacy with only one IUD.[18] Evidence is lacking regarding progestogen IUD usage for menorrhagia in bicornuate uterus, but a case report showed good effect with a single IUD for this purpose.[19]

Breastfeeding

Progestogen-only contraceptives such as an IUD are not believed to affect milk supply or infant growth.[20] However, a study in the Mirena application for FDA approval found a lower continuation of breastfeeding at 75 days in hormonal IUD users (44%) versus copper IUD users (79%).[21]

When using Mirena, about 0.1% of the maternal dose of levonorgestrel can be transferred via milk to the nursed infant.[22] A six-year study of breastfed infants whose mothers used a levonorgestrel-only method of birth control found the infants had increased risk of respiratory infections and eye infections, though a lower risk of neurological conditions, compared to infants whose mothers used a copper IUD.[23] No longer-term studies have been performed to assess the long-term effects on infants of levonorgestrel in breast milk.

There are conflicting recommendations about use of Mirena while breastfeeding. The U.S. FDA does not recommend any hormonal method, including Mirena, as a first choice of contraceptive for nursing mothers. The World Health Organization recommends against immediate postpartum insertion, citing increased expulsion rates. It also reports concerns about potential effects on the infant's liver and brain development in the first six weeks postpartum. However, it recommends offering Mirena as a contraceptive option beginning at six weeks postpartum even to nursing women.[24] Planned Parenthood offers Mirena as a contraceptive option for breastfeeding women beginning at four weeks postpartum.[25]

Contraindications

A hormonal IUD should not be used by women who:

- Are, or think they may be, pregnant[9]

- Have abnormal vaginal bleeding that has not been explained[9]

- Have untreated cervical or uterine cancer[9]

- Have, or may have, breast cancer[9]

- Have abnormalities of the cervix or uterus[26]

- Have had pelvic inflammatory disease within the past 3 months[9]

- Have had an STI such as chlamydia or gonorrhea within the past 3 months[9]

- Have liver disease or tumor[26]

- Have an allergy to levonorgestrel or any of the inactive ingredients included in the device[26]

Insertion of an IUD is not recommended for women having had a D&E abortion (second-trimester abortion) within the past four weeks.[25] To reduce the risk of infection, insertion of an IUS is not recommended for women that have had a medical abortion but have not yet had an ultrasound to confirm that the abortion was complete, or that have not yet had their first menstruation following the medical abortion.[25]

A full list of contraindications can be found in the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use and the CDCUnited States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use.[9][27]

Adverse effects

- Irregular menstrual pattern: irregular bleeding and spotting is common in the first 3 to 6 months of use. After that time periods become shorter and lighter, and 20% of women stop having periods after 1 year of use.[28] The average user reports 16 days of bleeding or spotting in the first month of use, but this diminishes to about four days at 12 months.[29][30]

- Cramping and Pain: many women feel discomfort or pain during and immediately after insertion. Some women may have cramping for the first 1–2 weeks after insertion.[31]

- Expulsion: Sometimes the IUD can slip out of the uterus. This is termed expulsion. Around 5% of IUD users experience expulsion. If this happens a woman is not protected from pregnancy.[31][32] Expulsion is more common in younger women, women who have not had children, and when an IUD is inserted immediately after childbirth or abortion.[33][34][35]

- Perforation: Very rarely, the IUD can be pushed through the wall of the uterus during insertion. Risk of perforation is mostly determined by the skill of the practitioner performing the insertion. For experienced medical practitioners, the risk of perforation is 1 per 1,000 insertions or less.[36] With postpartum insertions, perforation of the uterus is more likely to occur when uterine involution is incomplete; involution usually completes by 4–6 weeks postpartum.[34] Special considerations apply to women who plan to breastfeed. If perforation does occur it can damage the internal organs, and in some cases surgery is needed to remove the IUD.

- Pregnancy complications: Although the risk of pregnancy with an IUD is very small, if one does occur there is an increased risk of serious problems. These include ectopic pregnancy, infection, miscarriage, and early labor and delivery. As many as half the pregnancies that occur in Mirena users may be ectopic. The incidence rate of ectopic pregnancies is approximately 1 per 1000 users per year.[37] Immediate removal the IUD is recommended in the case of pregnancy.[31][32] No pattern of birth defects was found in the 35 babies for whom birth outcomes were available at the time of FDA approval.[38]

- Infection: The insertion of the IUD does have a small risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Concurrent infection with gonorrhea or chlamydia at the time of insertion increases the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease.[39] If PID does occur, it will most likely happen within 21 days of insertion. The device itself does not increase the risk of infection.[31]

- Ovarian Cysts: Enlarged follicles (ovarian cysts) have been diagnosed in about 12% of the subjects using a hormonal IUD. Most of these follicles are asymptomatic, although some may be accompanied by pelvic pain or dyspareunia. In most cases the enlarged follicles disappear spontaneously after two to three months. Surgical intervention is not usually required.[40]

- Mental health changes including: nervousness, depressed mood, mood swings[26]

- Weight gain[26]

- Headache, migraine[26]

- Nausea[26]

- Acne[26]

- Excessive hairiness[26]

- Lower abdominal or back pain[26]

- Decreased libido[26]

- Itching, redness or swelling of the vagina[26]

- Vaginal discharge[41]

- Breast pain, tenderness[41]

- Edema[41]

- Abdominal distension[41]

- Cervicitis [41]

- May affect glucose tolerance [41]

- May experience a change in vision or contact lens tolerance [12]

- May deplete Vitamin B1 which can affect energy, mood, and nervous system functioning [12]

- A "lost coil" occurs when the thread cannot be felt by a woman on routine checking and is not seen on speculum examination.[42] Various thread collector devices or simple forceps may then be used to try to grasp the device through the cervix.[43] In the rare cases when this is unsuccessful, an ultrasound scan may be arranged to check the position of the coil and exclude its perforation through into the abdominal cavity or its unrecognised previous expulsion.

Cancer

According to a 1999 evaluation of the studies performed on progestin-only birth control by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, there is some evidence that progestin-only birth control reduces the risk of endometrial cancer. The IARC concluded that there is no evidence progestin-only birth control increases the risk of any cancer, though the available studies were too small to be definitively conclusive.[44]

In a study of over 93,000 Finnish women who used the Mirena IUD between 1994 and 2007, researchers discovered a significant increase in breast cancer among Mirena users between the age of 45-49 compared to women of the same age who did not use the IUD.[45]

Bone density

No evidence has been identified to suggest Mirena affects bone mineral density (BMD).[46] Two small studies, limited to studying BMD in the forearm, show no decrease in BMD.[47][48] One of the studies showed at 7 years of use, similar BMD at the midshaft of the ulna and at the distal radius as nonusers matched by age and BMI.[47] In addition, BMD measurements were similar to the expected values for women in the same age group as the participants. The authors of the study said their results were predictable, since it is well established that the main factor responsible for bone loss in women is hypoestrogenism, and, in agreement with previous reports, they found estradiol levels in Mirena users to be normal.[47]

Composition and hormonal release

The hormonal IUD is a small 'T'-shaped piece of plastic, which contains levonorgestrel, a type of progestin.[17] The cylinder of the device is coated with a membrane that regulates the release of the drug.[49] Mirena releases the drug at an initial rate of 20 micrograms per day. This declines to a rate of 14 micrograms per day after 5 years, which is still in the range of clinical effectiveness. Skyla releases 14 micrograms per day and declines to 5 micrograms per day after 3 years.[16] Jaydess releases 6 micrograms per day and lasts for 3 years.[50] In comparison, oral contraceptives can contain 150 micrograms of levonorgestrel.[31] The hormonal IUD releases the levonorgestrel directly into the uterus, as such its effects are mostly paracrine rather than systemic. Most of the drug stays inside the uterus, and only a small amount is absorbed into the rest of the body.[31] Blood levels of levonorgestrel in Mirena users are half those found in Norplant users and one-tenth those found in users of levonorgestrel-only pills).[51]

Insertion and removal

The hormonal IUD is inserted in a similar procedure to the nonhormonal copper IUD, and can only be inserted by a qualified medical practitioner.[31] Before insertion, a pelvic exam is performed to examine the shape and position of the uterus. It is also recommended that patients be tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia prior to insertion, as a current STI at the time of insertion can increase the risk of pelvic infection.[52] During the insertion, the vagina is held open with a speculum, the same device used during a pap smear.[31] A grasping instrument is used to steady the cervix, the length of the uterus is measured for proper insertion, and the IUD is placed using a narrow tube through the opening of the cervix into the uterus.[31] A short length of monofilament plastic/nylon string hangs down from the cervix into the vagina. The string allows physicians and patients to check to ensure the IUD is still in place and enables easy removal of the device.[31] Mild to moderate cramping can occur during the procedure, which generally takes five minutes or less. Insertion can be performed immediately postpartum and post-abortion if no infection has occurred.[9] Misoprostol is not effective in reducing pain in IUD insertion.[53]

Removal of the device should also be performed by a qualified medical practitioner. After removal, fertility will return to previous levels relatively quickly.[54] One study found that the majority of participants returned to fertility within three months.[55]

Mechanisms of action

The hormonal IUD's primary mechanism of action is to prevent fertilization.[31][56][57][58][59] The levonorgestrel intrauterine system has several contraceptive effects:

- The inside of the uterus because fatal to sperm[60][58]

- Cervical mucus thickens[15]

- Ovulation is not inhibited[61]

Numerous studies have demonstrated that IUDs primarily prevent fertilization, not implantation.[31] In one experiment involving tubal flushing, fertilized eggs were found in half of women not using contraception, but no fertilized eggs were found in women using IUDs.[62] IUDs also decrease the risk of ectopic pregnancy, which further implies that IUDs prevent fertilization.[31]

History

Hormonal IUDs were developed in the 1990s following the development of the copper IUD in the 1960s and 1970s.[63] Dr. Antonio Scommenga, working at the Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, discovered that administering progesterone inside the uterus could have contraceptive benefits.[63] With knowledge of Scommegna's work, a Finnish doctor, Jouni Valtteri Tapani Luukkainen, created the 'T'-shaped IUD that released progesterone, marketed as the Progestasert System. This IUD had a short, 1-year lifespan and never achieved widespread popularity. Following this relative lack of success, Dr. Luukkainen replaced the progesterone with the hormone levonorgestrel to be released over a 5-year period, creating what is now Mirena.[64]

The Mirena IUD was studied for safety and efficacy in two clinical trials in Finland and Sweden involving 1,169 women who were all between 18 to 35 years of age at the beginning of the trials. The trials included predominantly Caucasian women who had been previously pregnant with no history of ectopic pregnancy or pelvic inflammatory disease within the previous year. Over 70% of the participants had previously used IUDs.[65]

In 2013 Skyla, a lower dose levonorgestrel IUD effective for up to 3 years, was approved by the FDA.[66] Skyla has a different bleeding pattern than Mirena, with only 6% of women in clinical trials becoming amenorrheic (compared to approximately 20% with Mirena). In 2015, Liletta was approved by the FDA. Liletta has a similar size and levonorgestrel release characteristics as Mirena, and is FDA-approved for 3 years of use following a study in which 6 women out of 1,751 conceived while using Liletta.[67]

Controversies

In 2009, Bayer, the maker of Mirena, was issued an FDA Warning Letter by the United States Food and Drug Administration for overstating the efficacy, minimizing the risks of use, and making "false or misleading presentations" about the device.[68][69] From 2000 to 2013, the federal agency received over 70,072 complaints about the device and related adverse effects.[70][71] Activist Erin Brockovich has launched a website for women who have experienced adverse effects to share their experiences.[72][73] Over 1,000 lawsuits have been filed in the United States.[69][74]

References

- 1 2 Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States.

- 1 2 3 4 Winner, B; Peipert, JF; Zhao, Q; Buckel, C; Madden, T; Allsworth, JE; Secura, GM. (2012), "Effectiveness of Long-Acting Reversible Contraception", New England Journal of Medicine 366 (21): 1998–2007, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110855, PMID 22621627

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Luis Bahamondes, M Valeria Bahamondes, Ilza Monteiro. (2008), "Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: uses and controversies.", Expert Review of Medical Devices 5 (4): 437–45, doi:10.1586/17434440.5.4.437, PMID 18573044

- ↑ Petta C, Ferriani R, Abrao M, Hassan D, Rosa E Silva J, Podgaec S, Bahamondes L (2005). "Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis.". Hum Reprod 20 (7): 1993–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh869. PMID 15790607.

- ↑ Sheng, J; Zhang, WY; Zhang, JP; Lu, D. (2009), "The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrheal associated with adenomyosis", Contraception 79 (3): 189–193, doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.11.004

- ↑ Faundes A, Alvarez F, Brache V, Tejada A (1988). "The role of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device in the prevention and treatment of iron deficiency anemia during fertility regulation". Int J Gynaecol Obstet 26 (3): 429–33. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(88)90341-4. PMID 2900174.

- ↑ Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C (2006). Marjoribanks, Jane, ed. "Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003855.pub2. PMID 16625593.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010), United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use

- ↑ "IUD". Planned Parenthood. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Convenience". Bayer. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Mirena". MediResource Inc. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 Hidalgo M, Bahamondes L, Perrotti M, Diaz J, Dantas-Monteiro C, Petta C (February 2002). "Bleeding patterns and clinical performance of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) up to two years.". Contraception 65 (2): 129–132. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00302-x. PMID 11927115. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ "Mirena (hormonal IUD)". Mayo Clinic. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 Sivin I, Stern J, Coutinho E, et al. (November 1991). "Prolonged intrauterine contraception: a seven-year randomized study of the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the Copper T380 Ag IUDS". Contraception 44 (5): 473–80. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(91)90149-a. PMID 1797462.

- 1 2 Highlights of Prescribing Information (Report). 9 January 2013.

- 1 2 , Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

- ↑ Amies Oelschlager, Anne-Marie; Debiec, Kate; Micks, Elizabeth; Prager, Sarah (2013). "Use of the Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System in Adolescents With Known Uterine Didelphys or Unicornuate Uterus". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 26 (2): e58. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.01.029. ISSN 1083-3188.

- ↑ Acharya GP, Mills AM (July 1998). "Successful management of intractable menorrhagia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, in a woman with a bicornuate uterus". J Obstet Gynaecol 18 (4): 392–3. doi:10.1080/01443619867263. PMID 15512123.

- ↑ Truitt S, Fraser A, Grimes D, Gallo M, Schulz K (2003). Lopez, Laureen M, ed. "Combined hormonal versus nonhormonal versus progestin-only contraception in lactation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003988. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003988. PMID 12804497.

- ↑ FDA Medical Review p. 37.

- ↑ MIRENA® Data Sheet, Bayer NZ, 11 December 2009http://www.bayerresources.com.au/resources/uploads/DataSheet/file9503.pdf Retrieved 2011-02-10

- ↑ Schiappacasse V, Díaz S, Zepeda A, Alvarado R, Herreros C (2002). "Health and growth of infants breastfed by Norplant contraceptive implants users: a six-year follow-up study". Contraception 66 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00319-0. PMID 12169382.

- ↑ "Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use" (PDF). Third Edition. World Health Organization. 2004: 101, 113. Retrieved 16 August 2006. pp.101, 113.

- 1 2 3 "Understanding IUDs". Planned Parenthood. July 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Mirena: Consumer Medicine Information" (PDF). Bayer. March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ WHO (2010). "Intrauterine devices (IUDs)". Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (4th ed.). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, WHO. ISBN 978 92 4 1563888.

- ↑ Hidalgo, M; Bahomondes, L; Perrottie, M; Diaz, J; Dantas-Monterio, C; Petta, CA. (2002), "Bleeding Patterns and clinical performance of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) up to two years", Contraception 65 (2): 129–132, doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00302-X, PMID 11927115

- ↑ McCarthy L (2006). "Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System (Mirena) for Contraception". Am Fam Physician 73 (10): 1799–. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ↑ Rönnerdag M, Odlind V (1999). "Health effects of long-term use of the intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system. A follow-up study over 12 years of continuous use". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 78 (8): 716–21. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780810.x. PMID 10468065.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Dean, Gillian; Schwarz, Eleanor Bimla (2011). "Intrauterine contraceptives (IUCs)". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 147–191. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. p.150:

Mechanism of action

Although the precise mechanism of action is not known, currently available IUCs work primarily by preventing sperm from fertilizing ova.26 IUCs are not abortifacients: they do not interrupt an implanted pregnancy.27 Pregnancy is prevented by a combination of the "foreign body effect" of the plastic or metal frame and the specific action of the medication (copper or levonorgestrel) that is released. Exposure to a foreign body causes a sterile inflammatory reaction in the intrauterine environment that is toxic to sperm and ova and impairs implantation.28,29 The production of cytotoxic peptides and activation of enzymes lead to inhibition of sperm motility, reduced sperm capacitation and survival, and increased phagocytosis of sperm.30,31… The progestin in the LNg IUC enhances the contraceptive action of the device by thickening cervical mucus, suppressing the endometrium, and impairing sperm function. In addition, ovulation is often impaired as a result of systemic absorption of levonorgestrel.23

p. 162:

Table 7-1. Myths and misconceptions about IUCs

Myth: IUCs are abortifacients. Fact: IUCs prevent fertilization and are true contraceptives. - 1 2 Population Information Program, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (1995), "IUDs—An Update", Population Reports XXII (5)

- ↑ IUDs—An Update. "Chapter 2.7:Expulsion".

- 1 2 IUDs—An Update. "Chapter 3.3 Postpartum Insertion".

- ↑ IUDs—An Update. "Chapter 3.4 Postabortion Insertion".

- ↑ World Health Organization (1987), Mechanisms of action, safety and efficacy of intrauterine devices: technical report series 753., Geneva

- ↑ FDA Medical Review pp. 3-4

- ↑ FDA Medical Review p. 5,41

- ↑ Grimes, DA (2000), "Intrauterine Device and upper-genital-tract infection", The Lancet 356: 1013–1019, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02699-4, PMID 11041414

- ↑ Bahamondes L, Hidalgo M, Petta CA, Diaz J, Espejo-Arce X, Monteiro-Dantas C. (2003), "Enlarged ovarian follicles in users of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and contraceptive implant", J. Reproduc. Med. 48 (8): 637–640, PMID 12971147

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Mirena". BayerUK. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Nijhuis J, Schijf C, Eskes T (1985). "The lost IUD: don't look too far for it". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 129 (30): 1409–10. PMID 3900746.

- ↑ Kaplan N (1976). "Letter: Lost IUD". Obstet Gynecol 47 (4): 508–9. PMID 1256735.

- ↑ "Hormonal Contraceptives, Progestogens Only". International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1999. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ↑ Willingham, Val (9 July 2014). "IUD may carry higher risk for breast cancer in certain women". CNN. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit (2004). "FFPRHC Guidance (April 2004). The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in contraception and reproductive health" (PDF). J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 30 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1783/147118904322995474. PMID 15086994.

- 1 2 3 Wong AY, Tang LC, Chin RK (2010). "Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) and Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depoprovera) as long-term maintenance therapy for patients with moderate and severe endometriosis: a randomised controlled trial.". Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 50 (3): 273–9. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01152.x. PMID 20618247.

- ↑ Bahamondes MV, Monteiro I, Castro S, Espejo-Arce X, Bahamondes L (2010). "Prospective study of the forearm bone mineral density of long-term users of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.". Hum Reprod 25 (5): 1158–64. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq043. PMID 20185512.

- ↑ Luukkainen, T. (1991), "Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Device", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 626: 43–49, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37898.x

- ↑ Römer, T.; Bühling, K. J. (2013). "Intrauterine hormonelle Kontrazeption". Gynäkologische Endokrinologie 11 (3): 188–196. doi:10.1007/s10304-012-0532-4.

- ↑ FDA Medical Review p.6

- ↑ Mohllajee, AP; Curtis, KM; Herbert, PB. (2006), "Does insertion and use of an intrauterine device increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with sexually transmitted infection? A systematic review", Contraception 73 (2): 145–153, doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.007

- ↑ Lopez, LM; Bernholc, A; Zeng, Y; Allen, RH; Bartz, D; O'Brien, PA; Hubacher, D (29 July 2015). "Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 7: CD007373. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007373.pub3. PMID 26222246.

- ↑ Mansour, D; Gemzell-Danielsson, K; Inki, Pirjo; Jensen, JT. (2011), "Fertility after discontinuation of contraception: a comprehensive review of the literature", Contraception 84 (5): 465–477, doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.04.002, PMID 22018120

- ↑ Randic, L; Vlasic, S; Matrljan, I; Waszak, C (1985), "Return to fertility after IUD removal for planned pregnancy", Contraception 32 (3): 253–259, doi:10.1016/0010-7824(85)90048-4

- ↑ Ortiz, María Elena; Croxatto, Horacio B. (June 2007). "Copper-T intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine system: biological bases of their mechanism of action". Contraception 75 (6 Suppl): S16‒S30. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.020. PMID 17531610. p. S28:

Conclusions

Active substances released from the IUD or IUS, together with products derived from the inflammatory reaction present in the luminal fluids of the genital tract, are toxic for spermatozoa and oocytes, preventing the encounter of healthy gametes and the formation of viable embryos. The current data do not indicate that embryos are formed in IUD users at a rate comparable to that of nonusers. The common belief that the usual mechanism of action of IUDs in women is destruction of embryos in the uterus is not supported by empirical evidence. The bulk of the data indicate that interference with the reproductive process after fertilization has taken place is exceptional in the presence of a T-Cu or LNG-IUD and that the usual mechanism by which they prevent pregnancy in women is by preventing fertilization. - ↑ ESHRE Capri Workshop Group (May–June 2008). "Intrauterine devices and intrauterine systems". Human Reproduction Update 14 (3): 197‒208. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn003. PMID 18400840. p. 199:

Mechanisms of action

Thus, both clinical and experimental evidence suggests that IUDs can prevent and disrupt implantation. It is unlikely, however, that this is the main IUD mode of action, … The best evidence indicates that in IUD users it is unusual for embryos to reach the uterus.

In conclusion, IUDs may exert their contraceptive action at different levels. Potentially, they interfere with sperm function and transport within the uterus and tubes. It is difficult to determine whether fertilization of the oocyte is impaired by these compromised sperm. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that IUDs can prevent and disrupt implantation. The extent to which this interference contributes to its contraceptive action is unknown. The data are scanty and the political consequences of resolving this issue interfere with comprehensive research.

p. 205:

Summary

IUDs that release copper or levonorgestrel are extremely effective contraceptives... Both copper IUDs and levonorgestrel releasing IUSs may interfere with implantation, although this may not be the primary mechanism of action. The devices also create barriers to sperm transport and fertilization, and sensitive assays detect hCG in less than 1% of cycles, indicating that significant prevention must occur before the stage of implantation. - 1 2 Speroff, Leon; Darney, Philip D. (2011). "Intrauterine contraception". A clinical guide for contraception (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 239–280. ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6. pp. 246–247:

Mechanism of action

The contraceptive action of all IUDs is mainly in the intrauterine cavity. Ovulation is not affected, and the IUD is not an abortifacient.58–60 It is currently believed that the mechanism of action for IUDs is the production of an intrauterine environment that is spermicidal.

Nonmedicated IUDs depend for contraception on the general reaction of the uterus to a foreign body. It is believed that this reaction, a sterile inflammatory response, produces tissue injury of a minor degree but sufficient enough to be spermicidal. Very few, if any, sperm reach the ovum in the fallopian tube.

The progestin-releasing IUD adds the endometrial action of the progestin to the foreign body reaction. The endometrium becomes decidualized with atrophy of the glands.65 The progestin IUD probably has two mechanisms of action: inhibition of implantation and inhibition of sperm capacitation, penetration, and survival. - ↑ Jensen, Jeffrey T.; Mishell, Daniel R. Jr. (2012). "Family planning: contraception, sterilization, and pregnancy termination". In Lentz, Gretchen M.; Lobo, Rogerio A.; Gershenson, David M.; Katz, Vern L. Comprehensive gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 215–272. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1. p. 259:

Intrauterine devices

Mechanisms of action

The common belief that the usual mechanism of action of IUDs in women is destruction of embryos in the uterus is not supported by empirical evidence... Because concern over mechanism of action represents a barrier to acceptance of this important and highly effective method for some women and some clinicians, it is important to point out that there is no evidence to suggest that the mechanism of action of IUDs is abortifacient.

The LNG-IUS, like the copper device, has a very low ectopic pregnancy rate. Therefore, fertilization does not occur and its main mechanism of action is also preconceptual. Less inflammation occurs within the uterus of LNG-IUS users, but the potent progestin effect thickens cervical mucus to impede sperm penetration and access to the upper genital track. Although the LNG-IUS also produces a thin, inactive endometrium, there is no evidence to suggest that this will prevent implantation, and the device should not be used for emergency contraception. - ↑ Guttinger, A; Critchley, HO (2007), "Endometrial effects of intrauterine levonorgestrel", Contraception 75 (6 Suppl.): S93–S98, doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.015, PMID 17531624

- ↑ Malik, S (January 2013). "Levonorgestrel-IUS system and endometrial manipulation.". Journal of mid-life health 4 (1): 6–7. PMID 23833526.

- ↑ Alvarez, F; Brache, V.; Fernandez, E; Guerrero, B; Guiloff, E; Hess, R; et al. (1988), "New insights on the mode of action of intrauterine contraceptive devices in women", Fertil Steril 49: 768–773, PMID 3360166

- 1 2 Thiery, M (1997), "Pioneers of the intrauterine device", The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Healthcare 2 (1): 15–23, doi:10.1080/13625189709049930, PMID 9678105

- ↑ Thiery, M (2000), "Intrauterine contraception: from silver ring to intrauterine implant", European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 90: 145–152, doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00262-1, PMID 10825633

- ↑ "MIRENA - levonorgestrel intrauterine device". Bayer Health Pharmaceuticals. May 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ FDA drug approval for Skyla

- ↑ Eisenberg, DL; Schreiber, CA; Turok, DK; Teal, SB; Westhoff, CL; Creinin, MD; ACCESS IUS, Investigators (July 2015). "Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.". Contraception 92 (1): 10–6. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.04.006. PMID 25934164.

- ↑ "2009 Warning Letters and Untitled Letters to Pharmaceutical Companies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 Bekiempis, Victoria (24 April 2014). "The Courtroom Controversy Behind Popular Contraceptive Mirena". Newsweek. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Budusun, Sarah. "Thousands of women complain about dangerous complications from Mirena IUD birth control". ABC Cleveland. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Colla, Connie (21 May 2013). "Mirena birth control may be causing complications in women". ABC 15 Arizona. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Mirena IUD". Erin Brockovich. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Anderson, Karen (5 December 2013). "I-Team: Birth Control Device Causing Serious Injuries". CBS Boston. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Mosher, Steven (20 November 2012). "The Mirena IUD is Becoming More Popular - and the Lawsuits are Piling Up". Population Research Institute. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

External links

- FDA (2000). "Medical review" (PDF scanned image). - on Berlex Laboratories' Mirena application

- Physician Fact Sheet (2008 U.S. version)

- Physician Fact Sheet (2013 U.K. version)

- Mirena drug description/side effects

- Video showing the insertion procedure for a Mirena IUD

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||