Interaction information

The interaction information (McGill 1954), or amounts of information (Hu Kuo Ting, 1962) or co-information (Bell 2003) is one of several generalizations of the mutual information, and expresses the amount information (redundancy or synergy) bound up in a set of variables, beyond that which is present in any subset of those variables. Unlike the mutual information, the interaction information can be either positive or negative. This confusing property has likely retarded its wider adoption as an information measure in machine learning and cognitive science. These functions, their negativity and minima have a direct interpretation in algebraic topology (Baudot & Bennequin, 2015).

The Three-Variable Case

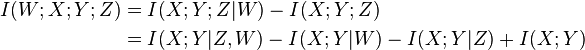

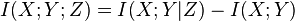

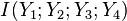

For three variables  , the interaction information

, the interaction information  is given by

is given by

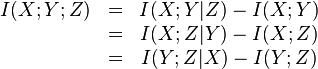

where, for example,  is the mutual information between variables

is the mutual information between variables  and

and  , and

, and  is the conditional mutual information between variables

is the conditional mutual information between variables  and

and  given

given  . Formally,

. Formally,

It thus follows that

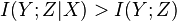

For the three-variable case, the interaction information  is the difference between the information shared by

is the difference between the information shared by  when

when  has been fixed and when

has been fixed and when  has not been fixed. (See also Fano's 1961 textbook.) Interaction information measures the influence of a variable

has not been fixed. (See also Fano's 1961 textbook.) Interaction information measures the influence of a variable  on the amount of information shared between

on the amount of information shared between  . Because the term

. Because the term  can be zero — for example, when the

dependency between

can be zero — for example, when the

dependency between  is due entirely to the influence of a common cause

is due entirely to the influence of a common cause  , the interaction information can be negative as well as positive. Negative interaction information indicates that variable

, the interaction information can be negative as well as positive. Negative interaction information indicates that variable  inhibits (i.e., accounts for or explains some of) the correlation between

inhibits (i.e., accounts for or explains some of) the correlation between  , whereas positive interaction information indicates that variable

, whereas positive interaction information indicates that variable  facilitates or enhances the correlation between

facilitates or enhances the correlation between  .

.

Interaction information is bounded. In the three variable case, it is bounded by

Example of Negative Interaction Information

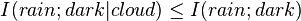

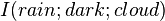

Negative interaction information seems much more natural than positive interaction information in the sense that such explanatory effects are typical of common-cause structures. For example, clouds cause rain and also block the sun; therefore, the correlation between rain and darkness is partly accounted for by the presence of clouds,  . The result is negative interaction information

. The result is negative interaction information  .

.

Example of Positive Interaction Information

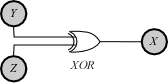

The case of positive interaction information seems a bit less natural. A prototypical example of positive  has

has  as the output of an XOR gate to which

as the output of an XOR gate to which  and

and  are the independent random inputs. In this case

are the independent random inputs. In this case  will be zero, but

will be zero, but  will be positive (1 bit) since once output

will be positive (1 bit) since once output  is known, the value on input

is known, the value on input  completely determines the value on input

completely determines the value on input  . Since

. Since  , the result is positive interaction information

, the result is positive interaction information  . It may seem that this example relies on a peculiar ordering of

. It may seem that this example relies on a peculiar ordering of  to obtain the positive interaction, but the symmetry of the definition for

to obtain the positive interaction, but the symmetry of the definition for  indicates that the same positive interaction information results regardless of which variable we consider as the interloper or conditioning variable. For example, input

indicates that the same positive interaction information results regardless of which variable we consider as the interloper or conditioning variable. For example, input  and output

and output  are also independent until input

are also independent until input  is fixed, at which time they are totally dependent (obviously), and we have the same positive interaction information as before,

is fixed, at which time they are totally dependent (obviously), and we have the same positive interaction information as before,  .

.

This situation is an instance where fixing the common effect  of causes

of causes  and

and  induces a dependency among the causes that did not formerly exist. This behavior is colloquially referred to as explaining away and is thoroughly discussed in the Bayesian Network literature (e.g., Pearl 1988). Pearl's example is auto diagnostics: A car's engine can fail to start

induces a dependency among the causes that did not formerly exist. This behavior is colloquially referred to as explaining away and is thoroughly discussed in the Bayesian Network literature (e.g., Pearl 1988). Pearl's example is auto diagnostics: A car's engine can fail to start  due either to a dead battery

due either to a dead battery  or due to a blocked fuel pump

or due to a blocked fuel pump  . Ordinarily, we assume that battery death and fuel pump blockage are independent events, because of the essential modularity of such automotive systems. Thus, in the absence of other information, knowing whether or not the battery is dead gives us no information about whether or not the fuel pump is blocked. However, if we happen to know that the car fails to start (i.e., we fix common effect

. Ordinarily, we assume that battery death and fuel pump blockage are independent events, because of the essential modularity of such automotive systems. Thus, in the absence of other information, knowing whether or not the battery is dead gives us no information about whether or not the fuel pump is blocked. However, if we happen to know that the car fails to start (i.e., we fix common effect  ), this information induces a dependency between the two causes battery death and fuel blockage. Thus, knowing that the car fails to start, if an inspection shows the battery to be in good health, we can conclude that the fuel pump must be blocked.

), this information induces a dependency between the two causes battery death and fuel blockage. Thus, knowing that the car fails to start, if an inspection shows the battery to be in good health, we can conclude that the fuel pump must be blocked.

Battery death and fuel blockage are thus dependent, conditional on their common effect car starting. What the foregoing discussion indicates is that the obvious directionality in the common-effect graph belies a deep informational symmetry: If conditioning on a common effect

increases the dependency between its two parent causes, then conditioning on one of the causes must create the same increase in dependency between the second cause and the common effect. In Pearl's automotive example, if conditioning on car starts induces  bits of dependency between the two causes battery dead and fuel blocked, then conditioning on

fuel blocked must induce

bits of dependency between the two causes battery dead and fuel blocked, then conditioning on

fuel blocked must induce  bits of dependency between battery dead and car starts. This may seem odd because battery dead and car starts are already governed by the implication battery dead

bits of dependency between battery dead and car starts. This may seem odd because battery dead and car starts are already governed by the implication battery dead  car doesn't start. However, these variables are still not totally correlated because the converse is not true. Conditioning on fuel blocked removes the major alternate cause of failure to start, and strengthens the converse relation and therefore the association between battery dead and car starts. A paper by Tsujishita (1995) focuses in greater depth on the third-order mutual information.

car doesn't start. However, these variables are still not totally correlated because the converse is not true. Conditioning on fuel blocked removes the major alternate cause of failure to start, and strengthens the converse relation and therefore the association between battery dead and car starts. A paper by Tsujishita (1995) focuses in greater depth on the third-order mutual information.

The Four-Variable Case

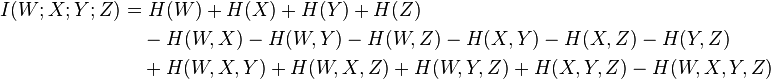

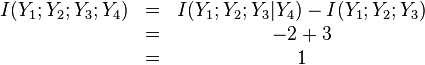

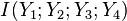

One can recursively define the n-dimensional interaction information in terms of the  -dimensional interaction information. For example, the four-dimensional interaction information can be defined as

-dimensional interaction information. For example, the four-dimensional interaction information can be defined as

or, equivalently,

The n-Variable Case

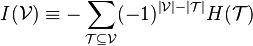

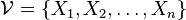

It is possible to extend all of these results to an arbitrary number of dimensions. The general expression for interaction information on variable set  in terms of the marginal entropies is given by Hu Kuo Ting (1962), Jakulin & Bratko (2003).

in terms of the marginal entropies is given by Hu Kuo Ting (1962), Jakulin & Bratko (2003).

which is an alternating (inclusion-exclusion) sum over all subsets  , where

, where  . Note

that this is the information-theoretic analog to the Kirkwood approximation.

. Note

that this is the information-theoretic analog to the Kirkwood approximation.

Difficulties Interpreting Interaction Information

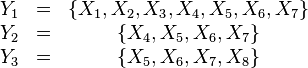

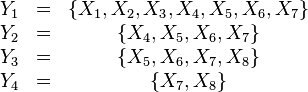

The possible negativity of interaction information can be the source of some confusion (Bell 2003). As an example of this confusion, consider a set of eight independent binary variables  . Agglomerate these variables as follows:

. Agglomerate these variables as follows:

Because the  's overlap each other (are redundant) on the three binary variables

's overlap each other (are redundant) on the three binary variables  , we would expect the interaction information

, we would expect the interaction information  to equal

to equal  bits, which it does. However, consider

now the agglomerated variables

bits, which it does. However, consider

now the agglomerated variables

These are the same variables as before with the addition of  . Because the

. Because the  's now overlap each other (are redundant) on only one binary variable

's now overlap each other (are redundant) on only one binary variable  , we would expect the interaction information

, we would expect the interaction information  to equal

to equal  bit. However,

bit. However,  in this case is actually equal to

in this case is actually equal to  bit,

indicating a synergy rather than a redundancy. This is correct in the sense that

bit,

indicating a synergy rather than a redundancy. This is correct in the sense that

but it remains difficult to interpret.

Uses of Interaction Information

- Jakulin and Bratko (2003b) provide a machine learning algorithm which uses interaction information.

- Killian, Kravitz and Gilson (2007) use mutual information expansion to extract entropy estimates from molecular simulations.

- LeVine and Weinstein (2014) use interaction information and other N-body information measures to quantify allosteric couplings in molecular simulations.

- Moore et al. (2006), Chanda P, Zhang A, Brazeau D, Sucheston L, Freudenheim JL, Ambrosone C, Ramanathan M. (2007) and Chanda P, Sucheston L, Zhang A, Brazeau D, Freudenheim JL, Ambrosone C, Ramanathan M. (2008) demonstrate the use of interaction information for analyzing gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions associated with complex diseases.

References

- Baudot, P.; Bennequin, D. (2015). "The homological nature of entropy". Entropy 17: 1–66. doi:10.3390/e17053253.

- Bell, A J (2003), The co-information lattice

- Fano, R M (1961), Transmission of Information: A Statistical Theory of Communications, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Garner W R (1962). Uncertainty and Structure as Psychological Concepts, JohnWiley & Sons, New York.

- Han, T S (1978). "Nonnegative entropy measures of multivariate symmetric correlations". Information and Control 36: 133–156. doi:10.1016/s0019-9958(78)90275-9.

- Han, T S (1980). "Multiple mutual information and multiple interactions in frequency data". Information and Control 46: 26–45. doi:10.1016/s0019-9958(80)90478-7.

- Hu Kuo Tin (1962), On the Amount of Information. Theory Probab. Appl.,7(4), 439-44. PDF

- Jakulin A & Bratko I (2003a). Analyzing Attribute Dependencies, in N Lavra\quad{c}, D Gamberger, L Todorovski & H Blockeel, eds, Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Springer, Cavtat-Dubrovnik, Croatia, pp. 229–240.

- Jakulin A & Bratko I (2003b). Quantifying and visualizing attribute interactions .

- Margolin, A; Wang, K; Califano, A; Nemenman, I (2010). "Multivariate dependence and genetic networks inference". IET Syst Biol 4: 428–440. doi:10.1049/iet-syb.2010.0009.

- McGill, W J (1954). "Multivariate information transmission". Psychometrika 19: 97–116. doi:10.1007/bf02289159.

- Moore JH, Gilbert JC, Tsai CT, Chiang FT, Holden T, Barney N, White BC (2006). A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility, Journal of Theoretical Biology 241, 252-261.

- Nemenman I (2004). Information theory, multivariate dependence, and genetic network inference .

- Pearl, J (1988), Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference, Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, CA.

- Tsujishita, T (1995), On triple mutual information, Advances in applied mathematics 16, 269-274.

- Chanda, P; Zhang, A; Brazeau, D; Sucheston, L; Freudenheim, JL; Ambrosone, C; Ramanathan, M (2007). "Information-theoretic metrics for visualizing gene-environment interactions". American Journal of Human Genetics 81 (5): 939–63. doi:10.1086/521878. PMC 2265645. PMID 17924337.

- Chanda, P; Sucheston, L; Zhang, A; Brazeau, D; Freudenheim, JL; Ambrosone, C; Ramanathan, M (2008). "AMBIENCE: a novel approach and efficient algorithm for identifying informative genetic and environmental associations with complex phenotypes". Genetics 180 (2): 1191–210. doi:10.1086/521878. PMC 2265645. PMID 17924337.

- Killian, B J; Kravitz, J Y; Gilson, M K (2007). "Extraction of configurational entropy from molecular simulations via an expansion approximation". J. Chem. Phys. 127: 024107. doi:10.1063/1.2746329.

- LeVine MV, Weinstein H (2014), NbIT - A New Information Theory-Based Analysis of Allosteric Mechanisms Reveals Residues that Underlie Function in the Leucine Transporter LeuT. PLoS Computational Biology.

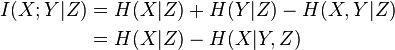

![\begin{align}

I(X;Y;Z) = & - [ H(X) + H(Y) + H(Z) ] \\

& + [ H(X,Y) + H(X,Z) + H(Y,Z) ] \\

& - H(X,Y,Z)

\end{align}](../I/m/226ebe30ce6fe4288c8fa710729fff8c.png)