Separable extension

In the subfield of algebra named field theory, a separable extension is an algebraic field extension  such that for every

such that for every  , the minimal polynomial of

, the minimal polynomial of  over F is a separable polynomial (i.e., has distinct roots; see below for the definition in this context).[1] Otherwise, the extension is called inseparable. There are other equivalent definitions of the notion of a separable algebraic extension, and these are outlined later in the article.

over F is a separable polynomial (i.e., has distinct roots; see below for the definition in this context).[1] Otherwise, the extension is called inseparable. There are other equivalent definitions of the notion of a separable algebraic extension, and these are outlined later in the article.

The importance of separable extensions lies in the fundamental role they play in Galois theory in finite characteristic. More specifically, a finite degree field extension is Galois if and only if it is both normal and separable.[2] Since algebraic extensions of fields of characteristic zero, and of finite fields, are separable, separability is not an obstacle in most applications of Galois theory.[3][4] For instance, every algebraic (in particular, finite degree) extension of the field of rational numbers is necessarily separable.

Despite the ubiquity of the class of separable extensions in mathematics, its extreme opposite, namely the class of purely inseparable extensions, also occurs quite naturally. An algebraic extension  is a purely inseparable extension if and only if for every

is a purely inseparable extension if and only if for every  , the minimal polynomial of

, the minimal polynomial of  over F is not a separable polynomial (i.e., does not have distinct roots).[5] For a field F to possess a non-trivial purely inseparable extension, it must necessarily be an infinite field of prime characteristic (i.e. specifically, imperfect), since any algebraic extension of a perfect field is necessarily separable.[3]

over F is not a separable polynomial (i.e., does not have distinct roots).[5] For a field F to possess a non-trivial purely inseparable extension, it must necessarily be an infinite field of prime characteristic (i.e. specifically, imperfect), since any algebraic extension of a perfect field is necessarily separable.[3]

Informal discussion

An arbitrary polynomial f with coefficients in some field F is said to have distinct roots if and only if it has deg(f) roots in some extension field  . For instance, the polynomial g(X)=X2+1 with real coefficients has precisely deg(g)=2 roots in the complex plane; namely the imaginary unit i, and its additive inverse −i, and hence does have distinct roots. On the other hand, the polynomial h(X)=(X−2)2 with real coefficients does not have distinct roots; only 2 can be a root of this polynomial in the complex plane and hence it has only one, and not deg(h)=2 roots.

. For instance, the polynomial g(X)=X2+1 with real coefficients has precisely deg(g)=2 roots in the complex plane; namely the imaginary unit i, and its additive inverse −i, and hence does have distinct roots. On the other hand, the polynomial h(X)=(X−2)2 with real coefficients does not have distinct roots; only 2 can be a root of this polynomial in the complex plane and hence it has only one, and not deg(h)=2 roots.

To test if a polynomial has distinct roots, it is not necessary to consider explicitly any field extension nor to compute the roots: a polynomial has distinct roots if and only if the greatest common divisor of the polynomial and its derivative is a constant.

For instance, the polynomial g(X)=X2+1 in the above paragraph, has 2X as derivative, and, over a field of characteristic different from 2, we have g(X) - (1/2 X) 2X = 1, which proves, by Bézout's identity, that the greatest common divisor is a constant. On the other hand, over a field where 2=0, the greatest common divisor is g, and we have g(X) = (X+1)2 has 1=-1 as double root.

On the other hand, the polynomial h does not have distinct roots, whichever is the field of the coefficients, and indeed, h(X)=(X−2)2, its derivative is 2 (X-2) and divides it, and hence does have a factor of the form  for

for  ).

).

Although an arbitrary polynomial with rational or real coefficients may not have distinct roots, it is natural to ask at this stage whether or not there exists an irreducible polynomial with rational or real coefficients that does not have distinct roots. The polynomial h(X)=(X−2)2 does not have distinct roots but it is not irreducible as it has a non-trivial factor (X−2). In fact, it is true that there is no irreducible polynomial with rational or real coefficients that does not have distinct roots; in the language of field theory, every algebraic extension of  or

or  is separable and hence both of these fields are perfect.

is separable and hence both of these fields are perfect.

Separable and inseparable polynomials

A polynomial f in F[X] is a separable polynomial if and only if every irreducible factor of f in F[X] has distinct roots.[6] The separability of a polynomial depends on the field in which its coefficients are considered to lie; for instance, if g is an inseparable polynomial in F[X], and one considers a splitting field, E, for g over F, g is necessarily separable in E[X] since an arbitrary irreducible factor of g in E[X] is linear and hence has distinct roots.[1] Despite this, a separable polynomial h in F[X] must necessarily be separable over every extension field of F.[7]

Let f in F[X] be an irreducible polynomial and f' its formal derivative. Then the following are equivalent conditions for f to be separable; that is, to have distinct roots:

- If

and

and  , then

, then  does not divide f in E[X].[8]

does not divide f in E[X].[8] - There exists

such that f has deg(f) roots in K.[8]

such that f has deg(f) roots in K.[8] - f and f' do not have a common root in any extension field of F.[9]

- f' is not the zero polynomial.[10]

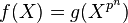

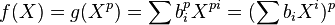

By the last condition above, if an irreducible polynomial does not have distinct roots, its derivative must be zero. Since the formal derivative of a positive degree polynomial can be zero only if the field has prime characteristic, for an irreducible polynomial to not have distinct roots its coefficients must lie in a field of prime characteristic. More generally, if an irreducible (non-zero) polynomial f in F[X] does not have distinct roots, not only must the characteristic of F be a (non-zero) prime number p, but also f(X)=g(Xp) for some irreducible polynomial g in F[X].[11] By repeated application of this property, it follows that in fact,  for a non-negative integer n and some separable irreducible polynomial g in F[X] (where F is assumed to have prime characteristic p).[12]

for a non-negative integer n and some separable irreducible polynomial g in F[X] (where F is assumed to have prime characteristic p).[12]

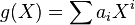

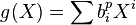

By the property noted in the above paragraph, if f is an irreducible (non-zero) polynomial with coefficients in the field F of prime characteristic p, and does not have distinct roots, it is possible to write f(X)=g(Xp). Furthermore, if  , and if the Frobenius endomorphism of F is an automorphism, g may be written as

, and if the Frobenius endomorphism of F is an automorphism, g may be written as  , and in particular,

, and in particular,  ; a contradiction of the irreducibility of f. Therefore, if F[X] possesses an inseparable irreducible (non-zero) polynomial, then the Frobenius endomorphism of F cannot be an automorphism (where F is assumed to have prime characteristic p).[13]

; a contradiction of the irreducibility of f. Therefore, if F[X] possesses an inseparable irreducible (non-zero) polynomial, then the Frobenius endomorphism of F cannot be an automorphism (where F is assumed to have prime characteristic p).[13]

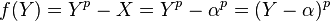

If K is a finite field of prime characteristic p, and if X is an indeterminant, then the field of rational functions over K, K(X), is necessarily imperfect. Furthermore, the polynomial f(Y)=Yp−X is inseparable.[1] (To see this, note that there is some extension field  in which f has a root

in which f has a root  ; necessarily,

; necessarily,  in E. Therefore, working over E,

in E. Therefore, working over E,  (the final equality in the sequence follows from freshman's dream), and f does not have distinct roots.) More generally, if F is any field of (non-zero) prime characteristic for which the Frobenius endomorphism is not an automorphism, F possesses an inseparable algebraic extension.[14]

(the final equality in the sequence follows from freshman's dream), and f does not have distinct roots.) More generally, if F is any field of (non-zero) prime characteristic for which the Frobenius endomorphism is not an automorphism, F possesses an inseparable algebraic extension.[14]

A field F is perfect if and only if all of its algebraic extensions are separable (in fact, all algebraic extensions of F are separable if and only if all finite degree extensions of F are separable). By the argument outlined in the above paragraphs, it follows that F is perfect if and only if F has characteristic zero, or F has (non-zero) prime characteristic p and the Frobenius endomorphism of F is an automorphism.

Properties

- If

is an algebraic field extension, and if

is an algebraic field extension, and if  are separable over F, then

are separable over F, then  and

and  are separable over F. In particular, the set of all elements in E separable over F forms a field.[15]

are separable over F. In particular, the set of all elements in E separable over F forms a field.[15] - If

is such that

is such that  and

and  are separable extensions, then

are separable extensions, then  is separable.[16] Conversely, if

is separable.[16] Conversely, if  is a separable algebraic extension, and if L is any intermediate field, then

is a separable algebraic extension, and if L is any intermediate field, then  and

and  are separable extensions.[17]

are separable extensions.[17] - If

is a finite degree separable extension, then it has a primitive element; i.e., there exists

is a finite degree separable extension, then it has a primitive element; i.e., there exists  with

with ![E=F[\alpha]](../I/m/55e2f89d43e3631374df81f20a13af90.png) . This fact is also known as the primitive element theorem or Artin's theorem on primitive elements.

. This fact is also known as the primitive element theorem or Artin's theorem on primitive elements.

Separable extensions within algebraic extensions

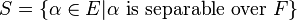

Separable extensions occur quite naturally within arbitrary algebraic field extensions. More specifically, if  is an algebraic extension and if

is an algebraic extension and if  , then S is the unique intermediate field that is separable over F and over which E is purely inseparable.[18] If

, then S is the unique intermediate field that is separable over F and over which E is purely inseparable.[18] If  is a finite degree extension, the degree [S : F] is referred to as the separable part of the degree of the extension

is a finite degree extension, the degree [S : F] is referred to as the separable part of the degree of the extension  (or the separable degree of E/F), and is often denoted by [E : F]sep or [E : F]s.[19] The inseparable degree of E/F is the quotient of the degree by the separable degree. When the characteristic of F is p > 0, it is a power of p.[20] Since the extension

(or the separable degree of E/F), and is often denoted by [E : F]sep or [E : F]s.[19] The inseparable degree of E/F is the quotient of the degree by the separable degree. When the characteristic of F is p > 0, it is a power of p.[20] Since the extension  is separable if and only if

is separable if and only if  , it follows that for separable extensions, [E : F]=[E : F]sep, and conversely. If

, it follows that for separable extensions, [E : F]=[E : F]sep, and conversely. If  is not separable (i.e., inseparable), then [E : F]sep is necessarily a non-trivial divisor of [E : F], and the quotient is necessarily a power of the characteristic of F.[19]

is not separable (i.e., inseparable), then [E : F]sep is necessarily a non-trivial divisor of [E : F], and the quotient is necessarily a power of the characteristic of F.[19]

On the other hand, an arbitrary algebraic extension  may not possess an intermediate extension K that is purely inseparable over F and over which E is separable (however, such an intermediate extension does exist when

may not possess an intermediate extension K that is purely inseparable over F and over which E is separable (however, such an intermediate extension does exist when  is a finite degree normal extension (in this case, K can be the fixed field of the Galois group of E over F)). If such an intermediate extension does exist, and if [E : F] is finite, then if S is defined as in the previous paragraph, [E : F]sep=[S : F]=[E : K].[21] One known proof of this result depends on the primitive element theorem, but there does exist a proof of this result independent of the primitive element theorem (both proofs use the fact that if

is a finite degree normal extension (in this case, K can be the fixed field of the Galois group of E over F)). If such an intermediate extension does exist, and if [E : F] is finite, then if S is defined as in the previous paragraph, [E : F]sep=[S : F]=[E : K].[21] One known proof of this result depends on the primitive element theorem, but there does exist a proof of this result independent of the primitive element theorem (both proofs use the fact that if  is a purely inseparable extension, and if f in F[X] is a separable irreducible polynomial, then f remains irreducible in K[X][22]). The equality above ([E : F]sep=[S : F]=[E : K]) may be used to prove that if

is a purely inseparable extension, and if f in F[X] is a separable irreducible polynomial, then f remains irreducible in K[X][22]). The equality above ([E : F]sep=[S : F]=[E : K]) may be used to prove that if  is such that [E : F] is finite, then [E : F]sep=[E : U]sep[U : F]sep.[23]

is such that [E : F] is finite, then [E : F]sep=[E : U]sep[U : F]sep.[23]

If F is any field, the separable closure Fsep of F is the field of all elements in an algebraic closure of F that are separable over F. This is the maximal Galois extension of F. By definition, F is perfect if and only if its separable and algebraic closures coincide (in particular, the notion of a separable closure is only interesting for imperfect fields).

The definition of separable non-algebraic extension fields

Although many important applications of the theory of separable extensions stem from the context of algebraic field extensions, there are important instances in mathematics where it is profitable to study (not necessarily algebraic) separable field extensions.

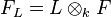

Let  be a field extension and let p be the characteristic exponent of

be a field extension and let p be the characteristic exponent of  .[24] For any field extension L of k, we write

.[24] For any field extension L of k, we write  (cf. Tensor product of fields.) Then F is said to be separable over

(cf. Tensor product of fields.) Then F is said to be separable over  if the following equivalent conditions are met:

if the following equivalent conditions are met:

and

and  are linearly disjoint over

are linearly disjoint over

is reduced.

is reduced. is reduced for all field extensions L of k.

is reduced for all field extensions L of k.

(In other words, F is separable over k if F is a separable k-algebra.)

A separating transcendence basis for F/k is an algebraically independent subset T of F such that F/k(T) is a finite separable extension. An extension E/k is separable if and only if every finitely generated subextension F/k of E/k has a separating transcendence basis.[25]

Suppose there is some field extension L of k such that  is a domain. Then

is a domain. Then  is separable over k if and only if the field of fractions of

is separable over k if and only if the field of fractions of  is separable over L.

is separable over L.

An algebraic element of F is said to be separable over  if its minimal polynomial is separable. If

if its minimal polynomial is separable. If  is an algebraic extension, then the following are equivalent.

is an algebraic extension, then the following are equivalent.

- F is separable over k.

- F consists of elements that are separable over k.

- Every subextension of F/k is separable.

- Every finite subextension of F/k is separable.

If  is finite extension, then the following are equivalent.

is finite extension, then the following are equivalent.

- (i) F is separable over k.

- (ii)

where

where  are separable over k.

are separable over k. - (iii) In (ii), one can take

- (iv) If K is an algebraic closure of k, then there are precisely

![[F : k]](../I/m/640c28946039b98be9ee191a4772aeb5.png) embeddings F into K which fix k.

embeddings F into K which fix k. - (v) If K is any normal extension of k such that F embeds into K in at least one way, then there are precisely

![[F : k]](../I/m/640c28946039b98be9ee191a4772aeb5.png) embeddings F into K which fix k.

embeddings F into K which fix k.

In the above, (iii) is known as the primitive element theorem.

Fix the algebraic closure  , and denote by

, and denote by  the set of all elements of

the set of all elements of  that are separable over k.

that are separable over k.  is then separable algebraic over k and any separable algebraic subextension of

is then separable algebraic over k and any separable algebraic subextension of  is contained in

is contained in  ; it is called the separable closure of k (inside

; it is called the separable closure of k (inside  ).

).  is then purely inseparable over

is then purely inseparable over  . Put in another way, k is perfect if and only if

. Put in another way, k is perfect if and only if  .

.

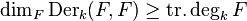

Differential criteria

The separability can be studied with the aid of derivations and Kähler differentials. Let  be a finitely generated field extension of a field

be a finitely generated field extension of a field  . Then

. Then

where the equality holds if and only if F is separable over k.

In particular, if  is an algebraic extension, then

is an algebraic extension, then  if and only if

if and only if  is separable.[26]

is separable.[26]

Let  be a basis of

be a basis of  and

and  . Then

. Then  is separable algebraic over

is separable algebraic over  if and only if the matrix

if and only if the matrix  is invertible. In particular, when

is invertible. In particular, when  ,

,  above is called the separating transcendence basis.

above is called the separating transcendence basis.

See also

- Purely inseparable extension

- Perfect field

- Primitive element theorem

- Normal extension

- Galois extension

- Algebraic closure

Notes

- 1 2 3 Isaacs, p. 281

- ↑ Isaacs, Theorem 18.13, p. 282

- 1 2 Isaacs, Theorem 18.11, p. 281

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 293

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 298

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 280

- ↑ Isaacs, Lemma 18.10, p. 281

- 1 2 Isaacs, Lemma 18.7, p. 280

- ↑ Isaacs, Theorem 19.4, p. 295

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 19.5, p. 296

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 19.6, p. 296

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 19.9, p. 298

- ↑ Isaacs, Theorem 19.7, p. 297

- ↑ Isaacs, p. 299

- ↑ Isaacs, Lemma 19.15, p. 300

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 19.17, p. 301

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 18.12, p. 281

- ↑ Isaacs, Theorem 19.14, p. 300

- 1 2 Isaacs, p. 302

- ↑ Lang 2002, Corollary V.6.2

- ↑ Isaacs, Theorem 19.19, p. 302

- ↑ Isaacs, Lemma 19.20, p. 302

- ↑ Isaacs, Corollary 19.21, p. 303

- ↑ The characteristic exponent of k is 1 if k has characteristic zero; otherwise, it is the characteristic of k.

- ↑ Fried & Jarden (2008) p.38

- ↑ Fried & Jarden (2008) p.49

References

- Borel, A. Linear algebraic groups, 2nd ed.

- P.M. Cohn (2003). Basic algebra

- Fried, Michael D.; Jarden, Moshe (2008). Field arithmetic. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete. 3. Folge 11 (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-77269-9. Zbl 1145.12001.

- I. Martin Isaacs (1993). Algebra, a graduate course (1st ed.). Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-19002-2.

- Kaplansky, Irving (1972). Fields and rings. Chicago lectures in mathematics (Second ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 55–59. ISBN 0-226-42451-0. Zbl 1001.16500.

- M. Nagata (1985). Commutative field theory: new edition, Shokado. (Japanese)

- Silverman, Joseph (1993). The Arithmetic of Elliptic Curves. Springer. ISBN 0-387-96203-4.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "separable extension of a field k", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4