Informal sector

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

By regional model |

|

Sectors |

|

Other types

|

|

| Grey market |

|---|

|

Legal aspects |

|

Related ideologies |

The informal sector, informal economy, or grey economy[1][2] is the part of an economy that is neither taxed, nor monitored by any form of government. Unlike the formal economy, activities of the informal economy are not included in the gross national product (GNP) and gross domestic product (GDP) of a country.[3] The informal sector can be described as a grey market in labour.

Other concepts which can be characterized as informal sector can include the black market (shadow economy, underground economy), the agorism, and System D. Associated idioms include "under the table", "off the books" and "working for cash".

Although the informal sector makes up a significant portion of the economies in developing countries – about 41% in 2000 according to the official GNI metric[4] – it is often stigmatized as troublesome and unmanageable. However the informal sector provides critical economy opportunities for the poor[3][5] and has been expanding rapidly since the 1960s.[6] As such, integrating the informal economy into the formal sector is an important policy challenge.[3]

Definition

The original use of the term ‘informal sector’ is attributed to the economic development model put forward by W. Arthur Lewis, used to describe employment or livelihood generation primarily within the developing world. It was used to describe a type of employment that was viewed as falling outside of the modern industrial sector.[7] An alternative definition uses job security as the measure of formality, defining participants in the informal economy as those 'who do not have employment security, work security and social security.”[8] While both of these definitions imply a lack of choice or agency in involvement with the informal economy, participation may also be driven by a wish to avoid regulation or taxation. This may manifest as unreported employment, hidden from the state for tax, social security or labour law purposes, but legal in all other aspects.[9]

The term is also useful in describing and accounting for forms of shelter or living arrangements that are similarly unlawful, unregulated, or not afforded protection of the state. ‘Informal economy’ is increasingly replacing ‘informal sector’[3] as the preferred descriptor for this activity.

Informality, both in housing and livelihood generation has often been seen as a social ill, and described either in terms of what participant’s lack, or wish to avoid. A countervailing view, put forward by prominent Dutch sociologist Saskia Sassen is that the modern or new ‘informal’ sector is the product and driver of advanced capitalism and the site of the most entrepreneurial aspects of the urban economy, led by creative professionals such as artists, architects, designers and software developers.[10] While this manifestation of the informal sector remains largely a feature of developed countries, increasingly systems are emerging to facilitate similarly qualified people in developing countries to participate[11]

Characteristics

The informal sector is largely characterized by several qualities: easy entry, meaning anyone who wishes to join the sector can find some sort of work which will result in cash earnings, a lack of stable employer-employee relationships,[12] a small scale of operations, and skills gained outside of a formal education.[3] Workers who participate in the informal economy are typically classified as employed. The type of work that makes up the informal economy is diverse, particularly in terms of capital invested, technology used, and income generated.[3][12] The spectrum ranges from self-employment or unpaid family labor[12] to street vendors, shoe shiners, and junk collectors.[3] On the higher end of the spectrum are upper-tier informal activities such as small-scale service or manufacturing businesses, which have more limited entry.[3][12] The upper-tier informal activities have higher set-up costs, which might include complicated licensing regulations, and irregular hours of operation.[12] However, most workers in the informal sector, even those are self-employed or wage workers, do not have access to secure work, benefits, welfare protection, or representation.[5] These features differ from businesses and employees in the formal sector which have regular hours of operation, a regular location and other structured benefits.[12]

The most prevalent types of work in the informal economy are home-based workers and street vendors. Home-based workers are more numerous while street vendors are more visible. Combined, the two fields make up about 10-15% of the non-agricultural workforce in developing countries and over 5% of the workforce in developed countries.[5]

While participation in the informal sector can be stigmatized, many workers engage in informal ventures by choice, for either economic or non-economic reasons. Economic motivations include the ability to evade taxes, the freedom to circumvent regulations and licensing requirements, and the capacity to maintain certain government benefits.[13] A study of informal workers in Costa Rica illustrated other economic reasons for staying in the informal sector, as well as non-economic factors. First, they felt they would earn more money through their informal sector work than at a job in the formal economy. Second, even if workers made less money, working in the informal sector offered them more independence, the chance to select their own hours, the opportunity to work outside and near friends, etc. While jobs in the formal economy might bring more security and regularity, or even pay better, the combination of monetary and psychological rewards from working in the informal sector proves appealing for many workers.[14]

The informal sector was historically recognized as an opposition to formal economy, meaning it included all income earning activities beyond legally regulated enterprises. However, this understanding is too inclusive and vague, and certain activities that could be included by that definition are not considered part of the informal economy. As the International Labor Organization defined the informal sector in 2002, the informal sector does not include the criminal economy. While production or employment arrangements in the informal economy may not be strictly legal, the sector produces and distributes legal goods and services. The criminal economy produces illegal goods and services.[5] The informal economy also does not include the reproductive or care economy, which is made up of unpaid domestic work and care activities. The informal economy is part of the market economy, meaning it produces goods and services for sale and profit. Unpaid domestic work and care activities do not contribute to that, and as a result, are not a part of the informal economy.[5]

History

Governments have tried to regulate (formalize) aspects of their economies for as long as surplus wealth has existed which is at least as early as Sumer. Yet no such regulation has ever been wholly enforceable. Archaeological and anthropological evidence strongly suggests that people of all societies regularly adjust their activity within economic systems in attempt to evade regulations. Therefore, if informal economic activity is that which goes unregulated in an otherwise regulated system then informal economies are as old as their formal counterparts, if not older. The term itself, however, is much more recent. The optimism of the modernization theory school of development had led most people in the 1950s and 1960s to believe that traditional forms of work and production would disappear as a result of economic progress in developing countries. As this optimism proved to be unfounded, scholars turned to study more closely what was then called the traditional sector. They found that the sector had not only persisted, but in fact expanded to encompass new developments. In accepting that these forms of productions were there to stay, scholars began using the term informal sector, which is credited to the British anthropologist Keith Hart in a study on Ghana in 1973 but also alluded to by the International Labour Organization in a widely read study on Kenya in 1972.

Since then the informal sector has become an increasingly popular subject of investigation, not just in economics, but also in sociology, anthropology and urban planning. With the turn towards so called post-fordist modes of production in the advanced developing countries, many workers were forced out of their formal sector work and into informal employment. In a seminal collection of articles, The Informal Economy. Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, Alejandro Portes and collaborators emphasized the existence of an informal economy in all countries by including case studies ranging from New York City and Madrid to Uruguay and Colombia.[15]

Arguably the most influential book on informal economy is Hernando de Soto's El otro sendero (1986),[16] which was published in English in 1989 as The Other Path with a preface by Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa.[17] De Soto and his team argue that excessive regulation in the Peruvian (and other Latin American) economies force a large part of the economy into informality and thus prevent economic development. While accusing the ruling class of 20th century mercantilism, de Soto admires the entrepreneurial spirit of the informal economy. In a widely cited experiment, his team tried to legally register a small garment factory in Lima. This took more than 100 administrative steps and almost a year of full-time work. Whereas de Soto's work is popular with policymakers and champions of free market policies like The Economist, many scholars of the informal economy have criticized it both for methodological flaws and normative bias.[18]

In the second half of the 1990s many scholars have started to consciously use the term "informal economy" instead of "informal sector" to refer to a broader concept that includes enterprises as well as employment in developing, transition, and advanced industrialized economies.

During this period, first surveys about the size and development of the shadow economy (mostly expressed in percent of official GDP) have been written by Feige (1989), Frey and Pommerehne (1984) and Schneider and Enste (2000). In these surveys an intensive discussion about the various estimation procedures of the size of the shadow economy as well as a critical evaluation of the size of the shadow economy and the consequences of the shadow economy on the official one can be found.[19][20][21]

Statistics

%2C_Ulan_Bator%2C_Mongolia.jpg)

The informal economy under any governing system is diverse and includes small-scaled, occasional members (often street vendors and garbage recyclers) as well as larger, regular enterprises (including transit systems such as that of Lima, Peru). Informal economies include garment workers working from their homes, as well as informally employed personnel of formal enterprises. Employees working in the informal sector can be classified as wage workers, non-wage workers, or a combination of both.[6]

Statistics on the informal economy are unreliable by virtue of the subject, yet they can provide a tentative picture of its relevance: For example, informal employment makes up 48% of non-agricultural employment in North Africa, 51% in Latin America, 65% in Asia, and 72% in sub-Saharan Africa. If agricultural employment is included, the percentages rise, in some countries like India and many sub-Saharan African countries beyond 90%. Estimates for developed countries are around 15%.[5]

In developing countries, the largest part of informal work, around 70%, is self-employed. Wage employment predominates. The majority of informal economy workers are women. Policies and developments affecting the informal economy have thus a distinctly gendered effect.

Estimated size of countries' informal economy

To estimate the size and development of a shadow economy is quite a challenging task and meanwhile there exist numerous different estimations of the size of the shadow economy for countries all over the world. In the following two tables the size of the shadow economy (underground economy) relative to GNP in various OECD-countries (table 1) as well as in various developing and transition countries (table 2) for the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s are shown. For the OECD-countries, the estimates of the size of the shadow economy in the mid-1990s are mostly estimated by the currency demand approach, whereas for the mid-2000s the MIMIC approach was used. The currency demand and the MIMIC approach are extensively described and criticized in Schneider and Enste (2000) and in Schneider and Collins (2013). In table 2, where the underground economy for various developing and transition countries is shown, the estimates for the mid-1990s are undertaken with the physical input (electricity) demand approach and for the mid-2000s also with the MIMIC approach. Here we also observe quite drastic differences as these two estimation procedures are only roughly comparable. The first table clearly shows that in OECD countries the size and development of the shadow economy in the mid-2000s is considerably lower than the one in the mid-1990s. This holds for some developing and transition countries as well but not for all, for example not for Slovakia, Azerbaijan and Lithuania. Table 3 shows the size of the underground economy relative to GNP for selected West European countries and the United States over a much longer time period from the 1960s to 2013. Again we see quite different developments of the size and development of the shadow economy in these selected countries over time.[22][23][24][25][26][27]

|

Mid-1990s |

Mid-2000s | |

|---|---|---|

|

Greece |

27–30 % |

26-28 % |

|

Italy |

23-25 % | |

|

Spain |

20-22 % | |

|

Portugal |

20–24 % |

20-22 % |

|

Belgium |

19-21 % | |

|

Sweden |

16-18 % | |

|

Norway |

18–23 % |

16-18 % |

|

Denmark |

15-17 % | |

|

Ireland |

13-15 % | |

|

France |

13–16 % |

12-14 % |

|

Netherlands |

10-12 % | |

|

Germany |

15-17 % | |

|

Great Britain |

11-12 % | |

|

Japan |

9-10 % | |

|

United States |

8–10 % |

7-8 % |

|

Austria |

9-11 % | |

|

Switzerland |

8-9 % |

|

Mid-1990s |

Mid-2000s | |

|---|---|---|

|

Developing Countries | ||

|

Africa | ||

|

Nigeria |

68–76 % |

53-55 % |

|

Egypt |

33-35 % | |

|

Tunisia |

39–45 % |

31-33 % |

|

Morocco |

16-17 % | |

|

Central and South America | ||

|

Guatemala |

49-51 % | |

|

Mexico |

40–60 % |

28-30 % |

|

Peru |

55-58 % | |

|

Panama |

60-64 % | |

|

Chile |

18-19 % | |

|

Costa Rica |

25–35 % |

25-26 % |

|

Venezuela |

32-35 % | |

|

Brazil |

37-39 % | |

|

Paraguay |

37-38 % | |

|

Columbia |

35-37 % | |

|

Asia | ||

|

Thailand |

70 % |

48-50 % |

|

Philippines |

39-42 % | |

|

Sri Lanka |

38–50 % |

42-44 % |

|

Malaysia |

30-31 % | |

|

South Korea |

25-27 % | |

|

Hong Kong |

13 % |

15-16 % |

|

Singapore |

12-13 % | |

|

Transition Economies | ||

|

Central Europe | ||

|

Hungary |

24–28 % |

23-24 % |

|

Bulgaria |

33-35 % | |

|

Poland |

16–20 % |

26-27 % |

|

Romania |

30-32 % | |

|

Slovakia |

7–11 % |

17-18 % |

|

Czech Republic |

17-18 % | |

|

Former Soviet Union Countries | ||

|

Georgia |

63-65 % | |

|

Azerbaijan |

28–43 % |

53-58 % |

|

Ukraine |

46-48 % | |

|

Belarus |

44-46 % | |

|

Russia |

41-43 % | |

|

Lithuania |

20–27 % |

29-31 % |

|

Latvia |

27-29 % | |

|

Estonia |

29-31 % | |

|

1960 |

1995 |

Change from 1960 to 1995 in percentage points |

2005 |

2010 |

2013 |

Change from 2005 to 2013 in percentage points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sweden |

2.0 % |

16.0 % |

+14.0 % |

17.5 % |

15.0 % |

13.9 % |

-3.6 % |

|

Denmark |

4.5 % |

17.5 % |

+13.0 % |

16.5 % |

14.0 % |

13.0 % |

-3.5 % |

|

Norway |

1.5 % |

18.0 % |

+16.5 % |

17.6 % |

15.1 % |

13.6 % |

-4.0 % |

|

Germany |

2.0 % |

13.2 % |

+11.2 % |

15.4 % |

13.9 % |

12.4 % |

-3.0 % |

|

United States |

3.5 % |

9.5 % |

+6.0 % |

8.2 % |

7.2 % |

6.6 % |

-1.6 % |

|

Austria |

0.5 % |

7.0 % |

+6.5 % |

10.3 % |

8.2 % |

7.5 % |

-2.8 % |

|

Switzerland |

1.0 % |

6.7 % |

+5.7 % |

9.0 % |

8.1 % |

7.1 % |

-1.9 % |

The table below shows the estimated values of the size of the informal economy in 110 developing, transition and OECD countries.

The average size of the informal economy, as a percent of official GNI in the year 2000, in developing countries is 41%, in transition countries 38% and in OECD countries 18%.[4][28]

| Country | Informal economy (billions of current USD) 2000 | Informal economy in % of GNP 1999/2000 |

|---|---|---|

| | 2.1 | 67.3 |

| | 5.4 | 67.1 |

| | 6.0 | 64.1 |

| Azerbaijan | 3.0 | 60.6 |

| Peru | 31.1 | 59.9 |

| Zimbabwe | 4.2 | 59.4 |

| Tanzania | 5.2 | 58.3 |

| Nigeria | 21.3 | 57.9 |

| Thailand | 63.4 | 52.6 |

| Ukraine | 16.1 | 52.2 |

| Guatemala | 9.7 | 51.5 |

| Uruguay | 9.9 | 51.1 |

| Honduras | 2.9 | 49.6 |

| Zambia | 1.4 | 48.9 |

| Belarus | 14.4 | 48.1 |

| Armenia | 0.9 | 46.3 |

| Russia | 114.5 | 46.1 |

| Benin | 1.0 | 45.2 |

| | 1.0 | 45.2 |

| | 0.6 | 45.1 |

| | 7.1 | 44.6 |

| | 34.4 | 43.4 |

| | 1.9 | 43.2 |

| | 7.4 | 43.2 |

| | 2.7 | 43.1 |

| | 0.8 | 41.9 |

| | 0.9 | 41.0 |

| | 2.6 | 40.3 |

| | 0.7 | 40.3 |

| | 1.4 | 40.3 |

| | 3.4 | 39.9 |

| | 2.9 | 39.9 |

| | 226.8 | 39.8 |

| | 0.5 | 39.8 |

| | 1.5 | 39.6 |

| | 30.8 | 39.1 |

| | 0.8 | 38.4 |

| | 1.9 | 38.4 |

| | 7.1 | 38.4 |

| | 2.2 | 38.4 |

| | 4.3 | 36.9 |

| | 21.9 | 36.8 |

| | 11.8 | 36.4 |

| | 2.6 | 36.4 |

| | 16.7 | 35.6 |

| | 35.0 | 35.1 |

| | 4.3 | 34.4 |

| | 12.5 | 34.4 |

| | 3.5 | 34.3 |

| | 17.3 | 34.1 |

| | 5.9 | 34.1 |

| | 1.6 | 34.1 |

| | 2.5 | 34.1 |

| | 40.1 | 33.6 |

| | 1.8 | 33.4 |

| | 1.3 | 33.4 |

| | 6.3 | 33.4 |

| Cameroon | 2.7 | 32.8 |

| Turkey | 64.5 | 32.1 |

| Dominican Republic | 6.0 | 32.1 |

| Malaysia | 25.6 | 31.1 |

| | 3.4 | 30.3 |

| | 168.5 | 30.1 |

| | 2.5 | 29.1 |

| | 32.9 | 28.6 |

| | 34.8 | 28.4 |

| | 43.3 | 27.6 |

| | 125.1 | 27.5 |

| | 2.0 | 27.4 |

| | 4.9 | 27.1 |

| | 288.0 | 27.0 |

| | 0.0 | 26.4 |

| | 3.8 | 26.2 |

| | 70.5 | 25.4 |

| | 11.1 | 25.1 |

| | 53.1 | 23.2 |

| | 104.7 | 23.1 |

| | 23.3 | 22.6 |

| | 124.8 | 22.6 |

| | 23.2 | 21.9 |

| | 13.5 | 19.8 |

| | 61.6 | 19.6 |

| | 27.7 | 19.4 |

| | 1.6 | 19.4 |

| | 3.1 | 19.3 |

| | 9.6 | 19.1 |

| | 30.6 | 19.1 |

| | 42.9 | 19.1 |

| | 17.7 | 18.9 |

| | 3.6 | 18.9 |

| | 0.2 | 18.4 |

| | 32.0 | 18.4 |

| | 21.9 | 18.3 |

| | 29.1 | 18.2 |

| | 27.5 | 16.6 |

| | 110.1 | 16.4 |

| | 303.1 | 16.3 |

| | 12.7 | 15.8 |

| | 4.9 | 15.6 |

| 199.6 | 15.3 | |

| 58.0 | 15.3 | |

| 139.6 | 13.1 | |

| 12.9 | 13.1 | |

| 47.8 | 13.0 | |

| 5.9 | 12.7 | |

| 178.6 | 12.6 | |

| 553.8 | 11.3 | |

| 19.0 | 10.2 | |

| 22.3 | 8.8 | |

| 864.6 | 8.8 |

Shadow economy on the European Single Market

Since the establishment of the Single Market (Maastricht 1993) the total EU shadow economy has been growing systematically to approx. 1.9 trillions € in preparation of the EURO[30] driven by the motor of the European shadow economy, Germany, which has been generating approx. 350 bn € per annum[29] since then (see also diagram on the right). Hence, the EU financial economy has developed parallel an efficient tax haven bank system to protect and manage its growing shadow economy. As per the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI 2013)[31] currently Germany and some neighbouring countries, range among the world's top tax haven countries.

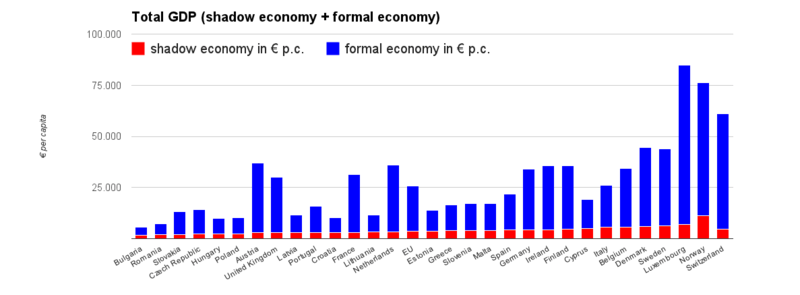

The diagram below clearly shows that informal economy per capita is in most EU countries on a similar level with only slight differences. It is because according to the Human Development Index (HDI 2013) market sectors with high informal part (above 45%)[32] like "building and construction" or "agriculture" are rather homogeneously distributed over the countries, whereas sectors with low informal part (below 30%)[32] like "financial and business" (in Switzerland, Luxembourg), "public and personal services" (in Scandinavian countries) as well as "retail, wholesale and repair" are dominant in countries with extremely high GDP per capita i.e. industrially highly developed countries (HDI). Nevertheless, the diagram also shows that in absolute numbers the shadow economy per capita is related to the wealth of a society (GDP). Generally spoken, the higher GDP the higher shadow economy, albeit non-proportional.

On the other hand, there is a direct relation between high self-employment as well as high unemployment of a country to its above average shadow economy.[33] That might imply that the more salary-employed jobs (public or private) are available the less shadow economy is generated, because salary-employed people do not have time to contribute to the shadow economy considerably. However, this is only true for less industrialized countries where self-employment is common. In extremely highly industrialized countries where shadow economy (per capita) is high and the huge private sector is shared by an extremely small elite of entrepreneurs a considerable part of tax evasion is practised by a much smaller number of (elite) people. As an example German shadow economy in 2013 was 4.400 € per capita, which was the 9th highest place in EU, whereas according to OECD only 5% of the population was self-employed (place 18).[34] On the other side Romania's shadow economy was only 2.000 € p.c (place 27) but self-employment was 9% (place 3 after PT=9.4% and GR=11.4%)

An extreme example of masked shadow economy is Luxembourg where the relative annual shadow economy is only 8% of the GDP which is the second lowest percentage (2013) of all EU countries whereas its real size (6.800 € per capita) is the highest.

Social and political implications and issues

According to development and transition theories, workers in the informal sector typically earn less income, have unstable income, and do not have access to basic protections and services.[36][37] The informal economy is also much larger than most people realize, with women playing a huge role. The working poor, particularly women, are concentrated in the informal economy, and most low-income households rely on the sector to provide for them.[5] However, informal businesses can also lack the potential for growth, trapping employees in menial jobs indefinitely. On the other hand, the informal sector can allow a large proportion of the population to escape extreme poverty and earn an income that is satisfactory for survival.[38] Also, in developed countries, some people who are formally employed may choose to perform part of their work outside of the formal economy, exactly because it delivers them more advantages. This is called 'moonlighting'. They derive social protection, pension and child benefits and the like, from their formal employment, and at the same time have tax and other advantages from working on the side.

From the viewpoint of governments, the informal sector can create a vicious cycle. Being unable to collect taxes from the informal sector, the government may be hindered in financing public services, which in turn makes the sector more attractive. Conversely, some governments view informality as a benefit, enabling excess labor to be absorbed, and mitigating unemployment issues.[38] Recognizing that the informal economy can produce significant goods and services, create necessary jobs, and contribute to imports and exports is critical for governments.[5]

Gender

Women tend to make up the greatest portion of the informal sector, often ending up in the most erratic and corrupt segments of the sector.[36] In developing countries, most of the female non-agricultural labor force is in the informal sector.[39] [40] Major occupations in the informal sector include home-based workers (such as dependent subcontract workers, independent own account producers, and unpaid workers in family businesses) and street vendors, which both are classified in the informal sector.[41] In India, women working in the informal sector often work as ragpickers, domestic workers, coolies, vendors, beauticians, construction laborers, and garment workers.[42]

Female representation in the informal sector is attributed to a variety of factors. One such factor is the fact that employment in the informal sector is the source of employment that is most readily available to women.[41] A 2011 study of poverty in Bangladesh noted that cultural norms, religious seclusion, and illiteracy among women in many developing countries, along with a greater commitment to family responsibilities, prevent women from entering the formal sector.[43]

According to a 2002 study commissioned by the ILO, the connection between employment in the informal economy and being poor is stronger for women than men.[6] While men tend to be overrepresented in the top segment of the informal sector, women overpopulate the bottom segment.[6][36] Men are more likely to have larger scale operations and deal in non-perishable items while few women are employers who hire others.[6] Instead, women are more likely to be involved in smaller scale operations and trade food items.[6] Women are under-represented in higher income employment positions in the informal economy and over-represented in lower income statuses.[6] As a result, the gender gap in terms of wage is even higher in the informal sector than the formal sector.[6] Labor markets, household decisions, and states all propagate this gender inequality.[36]

Political power of agents

Workers in the informal economy lack a significant voice in government policy.[13] Not only is the political power of informal workers limited, but the existence of the informal economy creates challenges for other politically influential actors. For example, the informal workforce is not a part of any trade union, nor does there seem a push or inclination to change that status. Yet the informal economy negatively affects membership and investment in the trade unions. Laborers who might be formally employed and join a union for protection may choose to branch out on their own instead. As a result, trade unions are inclined to oppose the informal sector, highlighting the costs and disadvantages of the system. Producers in the formal sector can similarly feel threatened by the informal economy. The flexibility of production, low labor and production costs, and bureaucratic freedom of the informal economy can be seen as consequential competition for formal producers, leading them to challenge and object to that sector. Last, the nature of the informal economy is largely anti-regulation and free of standard taxes, which diminishes the material and political power of government agents. Whatever the significance of these concerns are, the informal sector can shift political power and energies.[13]

Poverty

The relationship between the informal sectors and poverty certainly is not simple nor does a clear, causal relationship exist. An inverse relationship between an increased informal sector and slower economic growth has been observed though.[36]

Average incomes are substantially lower in the informal economy and there is a higher preponderance of impoverished employees working in the informal sector.[44] In addition, workers in the informal economy are less likely to benefit from employment benefits and social protection programs.[5]

Children

_-_Egypt-12B-051.jpg)

Children work in the informal economy in many parts of the world. They often work as scavengers (collecting recyclables from the streets and dump sites), day laborers, cleaners, construction workers, vendors, in seasonal activities, domestic workers, and in small workshops; and often work under hazardous and exploitative conditions. [45][46] It is common for children to work as domestic servants across Latin America and parts of Asia. Such children are very vulnerable to exploitation: often they are not allowed to take breaks or are required to work long hours; many suffer from a lack of access to education, which can contribute to social isolation and a lack of future opportunity. UNICEF considers domestic work to be among the lowest status, and reports that most child domestic workers are live-in workers and are under the round-the-clock control of their employers.[47] Some estimates suggest that among girls, domestic work is the most common form of employment.[48]

Expansion and growth

The informal sector has been expanding as more economies have started to liberalize.[36] This pattern of expansion began in the 1960s when a lot of developing countries didn’t create enough formal jobs in their economic development plans, which led to the formation of an informal sector that didn’t solely include marginal work and actually contained profitable opportunities.[6] In the 1980s, the sector grew alongside formal industrial sectors. In the 1990s, an increase in global communication and competition led to a restructuring of production and distribution, often relying more heavily on the informal sector.[6] Over the past decade, the informal economy is said to account for more than half of the newly created jobs in Latin America. In Africa it accounts for around eighty percent.[6] Many explanations exist as to why the informal sector has been expanding in the developing world throughout the past few decades. It is possible that the kind of development that has been occurring has failed to support the increased labor force in a formal manner. Expansion can also be explained by the increased subcontracting due to globalization and economic liberalization. Finally, employers could be turning toward the informal sector to lower costs and cope with increased competition. Such extreme competition between industrial countries occurred after the expansion of the EC to markets of the then new member countries Greece, Spain and Portugal, and particularly after the establishment of the Single European Market (1993, Treaty of Maastricht). Mainly for French and German corporations it lead to systematic increase of their informal sectors under liberalized tax laws fostering thus their mutual competitiveness and against small local competitors. The continuous systematic increase of the German informal sector was stopped only after the establishment of the EURO and the execution of the Summer Olympic Games 2004,[49] which has been the first and (up to now) only in the Single Market. Since then the German informal sector stabilized on the achieved 350 bn € level which signifies an extremely high tax evasion for a country with 90% salary-employment.

According to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the key drivers for the growth of the informal economy in the twenty-first century include:[3]

- limited absorption of labour, particularly in countries with high rates of population or urbanisation;

- excessive cost and regulatory barriers of entry into the formal economy, often motivated by corruption;

- weak institutions, limiting education and training opportunities as well as infrastructure development;

- increasing demand for low-cost goods and services;

- migration motivated by economic hardship and poverty; and

- difficulties faced by women in gaining formal employment

Historically, development theories have asserted that as economies mature and develop, economic activity will shift from the informal to the formal sphere. In fact, much of the economic development discourse is centered around the notion that formalization indicates how developed a country's economy is.[50] However, evidence suggests that the progression from informal to formal sectors is not universally applicable. While the characteristics of a formalized economy - full employment and an extensive welfare system - have served as effective methods of organizing work and welfare for some nations, such a structure is not necessarily inevitable or ideal. Indeed, development appears to be heterogeneous in different localities, regions, and nations, as well as the type of work practiced.[3][50] For example, at one end of the spectrum of the type of work practiced in the informal economy are small-scale businesses and manufacturing; on the other "street vendors, shoe shiners, junk collectors and domestic servants."[3] Regardless of how the informal economy develops, its continued growth that it cannot be considered a temporary phenomenon.[3]

Policy suggestions

As it has been historically stigmatized, policy perspectives viewed the informal sector as disruptive to the national economy and a hindrance to development.[51] The justifications for such criticisms include viewing the informal economy as a fraudulent activity that results in a loss of revenue from taxes, weakens unions, creates unfair competition, leads to a loss of regulatory control on the government's part, reduces observance of health and safety standards, and reduces the availability of employment benefits and rights. These characteristics have led to many nations pursuing a policy of deterrence with strict regulation and punitive procedures.[51]

In a 2004 report, the Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation under SIDA explained three perspectives on the role of government and policy in relation to the informal economy.[3]

- Markets function efficiently on their own; government interference would only lead to inefficiency and dysfunction.

- The informal economy functions outside of government control, largely because those who participate wish to avoid regulation and taxation.

- The informal economy is enduring; suitable regulation and policies are required.

As informal economy has significant job creation and income generation potential, as well as the capacity to meet the needs of poor consumers by providing cheaper and more accessible goods and services, many stakeholders subscribe to the third perspective and support government intervention and accommodation.[3][52] Embedded in the third perspective is the significant expectation that governments will revise policies that have favored the formal sphere at the expense of informal sector.[3]

Theories of how to accommodate the informal economy argue for government policies that, recognizing the value and importance of the informal sector, regulate and restrict when necessary but generally work to improve working conditions and increase efficiency and production.[3]

The challenge for policy interventions is that so many different types of informal work exist; a solution would have to provide for a diverse range of circumstances.[36] A possible strategy would be to provide better protections and benefits to informal sector players. However, such programs could lead to a disconnect between the labor market and protections, which would not actually improve informal employment conditions.[36] In a 2014 report monitoring street vending, WIEGO suggested urban planners and local economic development strategists study the carrying capacity of areas regularly used by informal workers and deliver the urban infrastructure necessary to support the informal economy, including running water and toilets, street lights and regular electricity, and adequate shelter and storage facilities.[52] That study also called for basic legal rights and protections for informal workers, such as appropriate licensing and permit practices.[52]

An ongoing policy debate considers the value of government tax breaks for household services such cleaning, babysitting and home maintenance, with an aim to reduce the shadow economy's impact. There are currently systems in place in Sweden[53] and France[54] which offer 50 percent tax breaks for home cleaning services. There has also been debate in the UK about introducing a similar scheme, with potentially large savings for middle-class families and greater incentive for women to return to work after having children.[55] The European Union has used political measures to try and curb the shadow economy. Although no definitive solution has been established to date, the EU council has led dialogue on a platform that would combat undeclared work.[56]

See also

References

- ↑ Dean Calbreath. "Hidden economy a hidden danger". U-T San Diego. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "Economics focus: In the shadows - The Economist". The Economist. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "The Informal Economy: Fact Finding Study" (PDF). Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- 1 2 Friedrich Schneider (July 2002). "SIZE AND MEASUREMENT OF THE INFORMAL ECONOMY IN 110 COUNTRIES AROUND THE WORLD" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Women and Men in the Informal Economy (PDF). International Labour Organisation. 2002. ISBN 92-2-113103-3. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Carr, Marilyn and Martha A. Chen. 2001. “Globalization and the Informal Economy: How Global Trade and Investment Impact on the Working Poor”. Background paper commissioned by the ILO Task Force on the Informal Economy. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- ↑ Lewis, William (1955). The Theory of Economic Growth. London: Allen and Unwin.

- ↑ Report on conditions of work and promotion of livelihoods in the unorganised sector. New Delhi: National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. 2007.

- ↑ Williams, Colin C. (2005). A Commodified World?: Mapping the limits of capitalism. London: Zed Books. pp. 73, 74.

- ↑ Jonatan Habib Engqvist and Maria Lantz, ed. (2009). Dharavi: documenting informalities. Delhi: Academic Foundation.

- ↑ Wilson, David (9 February 2012). "Jobs Giant: How Matt Barrie Build a Global Empire". The Age. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Meier, Gerald M.; Rauch, James E. (2005). Leading Issues in Economic Development (8 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 371–375.

- 1 2 3 Gërxhani, Klarita. "The Informal Sector in Developed and Less Developed Countries: A Literature Review". Public Choice 120 (3/4): 267–300.

- ↑ Meier, Gerald M.; Rauch, James E. (2005). Leading Issues in Economic Development (8 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 373.

- ↑ Alejandro Portes and William Haller (2005). "The Informal Economy". In N. Smelser and R. Swedberg (eds.). Handbook of Economic Sociology, 2nd edition. Russell Sage Foundation.

- ↑ Hernando de Soto (1986). El Otro Sendero. Sudamericana. ISBN 950-07-0441-2. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- ↑ Hernando de Soto (1989). The Other Path: The Economic Answer to Terrorism. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-016020-9.

- ↑ Davis, Mike (2006). Planet of Slums. London: Verso. pp. 79–82.

- ↑ Feige, E.L. (1989). The underground economies: Tax evasion and information distortion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Frey, B.S.; Pommerehne, W.W. (1984). pp. 1-23. "The hidden economy: state and prospect for measurement". Review of Income and Wealth (30/1).

- ↑ Schneider, F.; Enste, D. (2000). pp. 77-114. "Shadow economies: Size, causes and consequences". Journal of Economic Literature (38/1).

- ↑ Schneider, F. (2015). "Size and development of the shadow economy of 31 European and 5 other OECD countries from 2003 to 2014: Different developments?". Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics (3/4): 7–29.

- ↑ Buehn, A.; Schneider, F. (2012). "Shadow economies around the world: novel insights, accepted knowledge, and new estimates.". International Tax and Public Finance (19/1): 139–171.

- ↑ Schneider, F.; Buehn, A.; Montenegro, C. (2010). "New estimates for the shadow economies all over the world.". International Economic Journal (24/4): 443–461.

- ↑ Schneider, F.; Willams, C.C. (2013). "The shadow economy.". IEA, Institute for Economic Affairs (London).

- ↑ Feld, L.; Schneider, F. (2010). "Survey on the shadow economy and undeclared earnings in OECD countries.". German Economic Review (11/2): 109–149.

- ↑ Frey, B.S.; Schneider, F. (2015). "Informal and Underground Economics. In: James D. Wright (ed.)". International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.) (Oxford: Elsevier) 12: 50–55.

- ↑ http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2010/10/14/000158349_20101014160704/Rendered/PDF/WPS5356.pdf

- 1 2 German shadow economy

- ↑ https://www.atkearney.com/documents/10192/1743816/The+Shadow+Economy+in+Europe+2013.pdf

- ↑ http://www.financialsecrecyindex.com/introduction/fsi-2013-results

- 1 2 http://ftp.iza.org/dp6423.pdf The Shadow Economy and Shadow Economy Labour Force What Do We Not Know, Friedrich Schneider (page 30)

- ↑ Friedrich Schneider

- ↑ derived from OECD self-employment rate

- ↑ Schneider, Friedrich (2013). The Shadow Economy in Europe. University of Linz.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNRISD. 2010. “Gender Inequalities at Home and in the Market.” Assignment: Chapter 4, pp. 5-33.

- ↑ Beneria, Lourdes and Maria S. Floro. 2006. “Labor Market Informalization, Gender and Social Protection: Reflections on Poor Urban Households in Bolivia, Ecuador and Thailand,” in Shahra Razavi and Shireen Hassim, eds. Gender and Social Policy in a Global Context: Uncovering the Gendered Structure of “the Social,” pp. 193-216. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 1 2 Garcia-Bolivar, Omar E. 2006. “Informal economy: is it a problem, a solution, or both? The perspective of the informal business.’ Northwestern University School of : Law and Economics Papers. The Berkeley Electronic Press.

- ↑ http://www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpadocs/module6mc.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_21_November_2012/23.pdf

- 1 2 Chen, M (2001) “Women in the informal sector: a global picture, the global movementí.” SAIS Review 21(1).

- ↑ http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_21_November_2012/23.pdf

- ↑ Jahiruddin, ATM; Short, Patricia; Dressler, Wolfram; Khan, Adil (2011). "Can Microcredit Worsen Poverty? Cases of Exacerbated Poverty in Bangladesh". Development in Practice.

- ↑ Carr, Marilyn and Martha A. Chen. 2001. “Globalization and the Informal Economy: How Global Trade and Investment Impact on the Working Poor”. Background paper commissioned by the ILO Task Force on the Informal Economy. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- ↑ http://www.worldvision.org/resources.nsf/main/cambodia_childwork.pdf/$file/cambodia_childwork.pdf?Open

- ↑ http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/rep-vi.pdf

- ↑ "Counting Cinderellas Child Domestic Servants – Numbers and Trends".

- ↑ "Child domestic workers: Finding a voice" (PDF). Antislavery.com. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/20063/umfrage/entwicklung-des-umfangs-der-schattenwirtschaft-seit-1995/ shadow economy of Germany

- 1 2 Williams, Colin C.; Windebank, Jan (1998). Informal Employment in Advanced Economies: Implications for Work and Welfare. London: Routledge. p. 113.

- 1 2 Williams, Colin C. (2005). "The Undeclared Sector, Self-Employment and Public Policy". International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 11 (4): 244–257.

- 1 2 3 Roever, Sally (April 2014). "Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Street Vendors" (PDF). Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Skattereduktion för rot- och rutarbete". Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "Impots.gouv.fr - L'emploi d'un salarié à domicile". Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Ross, Tim (9 February 2012). "Tax breaks for hiring a cleaner could save middle class thousands". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ↑ "Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs" (PDF) (Press release). 19 June 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

Further reading

- Enrique Ghersi (1997). "The Informal Economy in Latin America" (PDF). Cato Journal (Cato Institute) 17 (1). Retrieved 2006-12-18. An article by a collaborator of de Soto.

- John C. Cross (January 1995). "Formalizing the informal economy: The Case of Street Vendors in Mexico City". Archived from the original on 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2006-12-18. A working paper describing attempts to formalize street vending in Mexico.

- World Institute for Development Economics Research (September 17–18, 2004). Unlocking Human Potential. United Nations University. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- Douglas Uzzell (November 22, 2004). "A Homegrown Mass Transit System in Lima, Peru: A Case of Generative Planning". City & Society 1 (1): 6–34. doi:10.1525/city.1987.1.1.6.

- Cheats or Contributors? Self Employed People in the Informal Economy A report by east London Charity Community Links and Microfinance organisation Street UK providing analysis of the motivations of informal workers.

- Need not Greed - People in low-paid informal work A report by east London Charity Community Links explores the experience of people on low incomes, doing informal paid work.

- World Bank policy note on The Informality Trap: Tax Evasion, Finance, and Productivity in Brazil

- World Bank policy note on Rising Informality - Reversing the Tide

- Paper estimating the size of the informal economy in 110 developing, transition and developed countries

- Keith Hart (2000). The Memory Bank. Profile Books. The link is to an online archive of Keith Hart's works.

- Frey, B.S. (1989). How large (or small) should the underground economy be? In E.L. Feige (Ed.), The underground economy: Tax evasion and information distortion, 111–129. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Temkin, Benjamin (2009). "Informal Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Entrepreneurship or Survivalist Strategy? Some Implications for Public Policy". Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 9 (1).

- Temkin, Benjamin; Jorge, Veizaga (2010). "The Impact of Economic Globalization on Labor Informality". New Global Studies 4 (1).

External links

- "The Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor". United Nations Development Program. Co-chaired by de Soto and former secretary of state Madeleine Albright.

- The Americas: Decent work - a rarity Independent news reports and features about the world of labour in the Americas by IPS Inter Press Service