Industrial wastewater treatment

Industrial wastewater treatment covers the mechanisms and processes used to treat wastewater that is produced as a by-product of industrial or commercial activities. After treatment, the treated industrial wastewater (or effluent) may be reused or released to a sanitary sewer or to a surface water in the environment. Most industries produce some wastewater although recent trends in the developed world have been to minimise such production or recycle such wastewater within the production process. However, many industries remain dependent on processes that produce wastewaters.

Sources of industrial wastewater

Complex organic chemicals industry

A range of industries manufacture or use complex organic chemicals. These include pesticides, pharmaceuticals, paints and dyes, petrochemicals, detergents, plastics, paper pollution, etc. Waste waters can be contaminated by feedstock materials, by-products, product material in soluble or particulate form, washing and cleaning agents, solvents and added value products such as plasticisers. Treatment facilities that do not need control of their effluent typically opt for a type of aerobic treatment, i.e. aerated lagoons.[1]

Electric power plants

Fossil-fuel power stations, particularly coal-fired plants, are a major source of industrial wastewater. Many of these plants discharge wastewater with significant levels of metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium and chromium, as well as arsenic, selenium and nitrogen compounds (nitrates and nitrites). Wastewater streams include flue-gas desulfurization, fly ash, bottom ash and flue gas mercury control. Plants with air pollution controls such as wet scrubbers typically transfer the captured pollutants to the wastewater stream.[2]

Ash ponds, a type of surface impoundment, are a widely used treatment technology at coal-fired plants. These ponds use gravity to settle out large particulates (measured as total suspended solids) from power plant wastewater. This technology does not treat dissolved pollutants. Power stations use additional technologies to control pollutants, depending on the particular wastestream in the plant. These include dry ash handling, closed-loop ash recycling, chemical precipitation, biological treatment (such as an activated sludge process), and evaporation.[2]

Food industry

Wastewater generated from agricultural and food operations has distinctive characteristics that set it apart from common municipal wastewater managed by public or private sewage treatment plants throughout the world: it is biodegradable and nontoxic, but that has high concentrations of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and suspended solids (SS).[3] The constituents of food and agriculture wastewater are often complex to predict due to the differences in BOD and pH in effluents from vegetable, fruit, and meat products and due to the seasonal nature of food processing and postharvesting.

Processing of food from raw materials requires large volumes of high grade water. Vegetable washing generates waters with high loads of particulate matter and some dissolved organic matter. It may also contain surfactants.

Animal slaughter and processing produces very strong organic waste from body fluids, such as blood, and gut contents. This wastewater is frequently contaminated by significant levels of antibiotics and growth hormones from the animals and by a variety of pesticides used to control external parasites. Insecticide residues in fleeces is a particular problem in treating waters generated in wool processing.

Processing food for sale produces wastes generated from cooking which are often rich in plant organic material and may also contain salt, flavourings, colouring material and acids or alkali. Very significant quantities of oil or fats may also be present.

Iron and steel industry

The production of iron from its ores involves powerful reduction reactions in blast furnaces. Cooling waters are inevitably contaminated with products especially ammonia and cyanide. Production of coke from coal in coking plants also requires water cooling and the use of water in by-products separation. Contamination of waste streams includes gasification products such as benzene, naphthalene, anthracene, cyanide, ammonia, phenols, cresols together with a range of more complex organic compounds known collectively as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH).

The conversion of iron or steel into sheet, wire or rods requires hot and cold mechanical transformation stages frequently employing water as a lubricant and coolant. Contaminants include hydraulic oils, tallow and particulate solids. Final treatment of iron and steel products before onward sale into manufacturing includes pickling in strong mineral acid to remove rust and prepare the surface for tin or chromium plating or for other surface treatments such as galvanisation or painting. The two acids commonly used are hydrochloric acid and sulfuric acid. Wastewaters include acidic rinse waters together with waste acid. Although many plants operate acid recovery plants (particularly those using hydrochloric acid), where the mineral acid is boiled away from the iron salts, there remains a large volume of highly acid ferrous sulfate or ferrous chloride to be disposed of. Many steel industry wastewaters are contaminated by hydraulic oil, also known as soluble oil.

Mines and quarries

The principal waste-waters associated with mines and quarries are slurries of rock particles in water. These arise from rainfall washing exposed surfaces and haul roads and also from rock washing and grading processes. Volumes of water can be very high, especially rainfall related arisings on large sites. Some specialized separation operations, such as coal washing to separate coal from native rock using density gradients, can produce wastewater contaminated by fine particulate haematite and surfactants. Oils and hydraulic oils are also common contaminants.

Wastewater from metal mines and ore recovery plants are inevitably contaminated by the minerals present in the native rock formations. Following crushing and extraction of the desirable materials, undesirable materials may enter the wastewater stream. For metal mines, this can include unwanted metals such as zinc and other materials such as arsenic. Extraction of high value metals such as gold and silver may generate slimes containing very fine particles in where physical removal of contaminants becomes particularly difficult.

Additionally, the geologic formations that harbour economically valuable metals such as copper and gold very often consist of sulphide-type ores. The processing entails grinding the rock into fine particles and then extracting the desired metal(s), with the leftover rock being known as tailings. These tailings contain a combination of not only undesirable leftover metals, but also sulphide components which eventually form sulphuric acid upon the exposure to air and water that inevitably occurs when the tailings are disposed of in large impoundments. The resulting acid mine drainage, which is often rich in heavy metals (because acids dissolve metals), is one of the many environmental impacts of mining.

- Mining processing chemicals

Nuclear industry

The waste production from the nuclear and radio-chemicals industry is dealt with as Radioactive waste.

Pulp and paper industry

Effluent from the pulp and paper industry is generally high in suspended solids and BOD. Stand alone paper mills using imported pulp may only require simple primary treatment, such as sedimentation or dissolved air flotation. Increased BOD or chemical oxygen demand (COD) loadings, as well as organic pollutants, may require biological treatment such as activated sludge or upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactors. For mills with high inorganic loadings like salt, tertiary treatments may be required, either general membrane treatments like ultrafiltration or reverse osmosis or treatments to remove specific contaminants, such as nutrients.

Water treatment

Many industries have a need to treat water to obtain very high quality water for demanding purposes. Water treatment produces organic and mineral sludges from filtration and sedimentation. Ion exchange using natural or synthetic resins removes calcium, magnesium and carbonate ions from water, typically replacing them with sodium, chloride, hydroxyl and/or other ions. Regeneration of ion exchange columns with strong acids and alkalis produces a wastewater rich in hardness ions which are readily precipitated out, especially when in admixture with other wastewater constituents.

Treatment of industrial wastewater

The various types of contamination of wastewater require a variety of strategies to remove the contamination.[4][5]

Brine treatment

Brine treatment involves removing dissolved salt ions from the waste stream. Although similarities to seawater or brackish water desalination exist, industrial brine treatment may contain unique combinations of dissolved ions, such as hardness ions or other metals, necessitating specific processes and equipment.

Brine treatment systems are typically optimized to either reduce the volume of the final discharge for more economic disposal (as disposal costs are often based on volume) or maximize the recovery of fresh water or salts. Brine treatment systems may also be optimized to reduce electricity consumption, chemical usage, or physical footprint.

Brine treatment is commonly encountered when treating cooling tower blowdown, produced water from steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD), produced water from natural gas extraction such as coal seam gas, frac flowback water, acid mine or acid rock drainage, reverse osmosis reject, chlor-alkali wastewater, pulp and paper mill effluent, and waste streams from food and beverage processing.

Brine treatment technologies may include: membrane filtration processes, such as reverse osmosis; ion exchange processes such as electrodialysis or weak acid cation exchange; or evaporation processes, such as brine concentrators and crystallizers employing mechanical vapour recompression and steam.

Reverse osmosis may not be viable for brine treatment, due to the potential for fouling caused by hardness salts or organic contaminants, or damage to the reverse osmosis membranes from hydrocarbons.

Evaporation processes are the most widespread for brine treatment as they enable the highest degree of concentration, as high as solid salt. They also produce the highest purity effluent, even distillate-quality. Evaporation processes are also more tolerant of organics, hydrocarbons, or hardness salts. However, energy consumption is high and corrosion may be an issue as the prime mover is concentrated salt water. As a result, evaporation systems typically employ titanium or duplex stainless steel materials.

Brine management

Brine management examines the broader context of brine treatment and may include consideration of government policy and regulations, corporate sustainability, environmental impact, recycling, handling and transport, containment, centralized compared to on-site treatment, avoidance and reduction, technologies, and economics. Brine management shares some issues with leachate management and more general waste management.

Solids removal

Most solids can be removed using simple sedimentation techniques with the solids recovered as slurry or sludge. Very fine solids and solids with densities close to the density of water pose special problems. In such case filtration or ultrafiltration may be required. Although, flocculation may be used, using alum salts or the addition of polyelectrolytes.

Oils and grease removal

Many oils can be recovered from open water surfaces by skimming devices. Considered a dependable and cheap way to remove oil, grease and other hydrocarbons from water, oil skimmers can sometimes achieve the desired level of water purity. At other times, skimming is also a cost-efficient method to remove most of the oil before using membrane filters and chemical processes. Skimmers will prevent filters from blinding prematurely and keep chemical costs down because there is less oil to process.

Because grease skimming involves higher viscosity hydrocarbons, skimmers must be equipped with heaters powerful enough to keep grease fluid for discharge. If floating grease forms into solid clumps or mats, a spray bar, aerator or mechanical apparatus can be used to facilitate removal.[6]

However, hydraulic oils and the majority of oils that have degraded to any extent will also have a soluble or emulsified component that will require further treatment to eliminate. Dissolving or emulsifying oil using surfactants or solvents usually exacerbates the problem rather than solving it, producing wastewater that is more difficult to treat.

The wastewaters from large-scale industries such as oil refineries, petrochemical plants, chemical plants, and natural gas processing plants commonly contain gross amounts of oil and suspended solids. Those industries use a device known as an API oil-water separator which is designed to separate the oil and suspended solids from their wastewater effluents. The name is derived from the fact that such separators are designed according to standards published by the American Petroleum Institute (API).[5][7]

The API separator is a gravity separation device designed by using Stokes Law to define the rise velocity of oil droplets based on their density and size. The design is based on the specific gravity difference between the oil and the wastewater because that difference is much smaller than the specific gravity difference between the suspended solids and water. The suspended solids settles to the bottom of the separator as a sediment layer, the oil rises to top of the separator and the cleansed wastewater is the middle layer between the oil layer and the solids.[5]

Typically, the oil layer is skimmed off and subsequently re-processed or disposed of, and the bottom sediment layer is removed by a chain and flight scraper (or similar device) and a sludge pump. The water layer is sent to further treatment consisting usually of an electroflotation module for additional removal of any residual oil and then to some type of biological treatment unit for removal of undesirable dissolved chemical compounds.

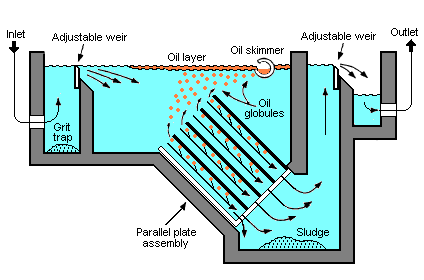

Parallel plate separators[8] are similar to API separators but they include tilted parallel plate assemblies (also known as parallel packs). The parallel plates provide more surface for suspended oil droplets to coalesce into larger globules. Such separators still depend upon the specific gravity between the suspended oil and the water. However, the parallel plates enhance the degree of oil-water separation. The result is that a parallel plate separator requires significantly less space than a conventional API separator to achieve the same degree of separation.

Hydrocyclone Oil Separators Hydrocyclone oil separators operate on the process where wastewater enters the cyclone chamber and is spun under extreme centrifugal forces up to 1000 times the force of gravity. This force causes the water and oil droplets to separate. The separated oil is discharged from one end of the cyclone where treated water is discharged through the opposite end for further treatment, filtration or discharge.[9]

Removal of biodegradable organics

Biodegradable organic material of plant or animal origin is usually possible to treat using extended conventional sewage treatment processes such as activated sludge or trickling filter.[4][5] Problems can arise if the wastewater is excessively diluted with washing water or is highly concentrated such as undiluted blood or milk. The presence of cleaning agents, disinfectants, pesticides, or antibiotics can have detrimental impacts on treatment processes.

Activated sludge process

Activated sludge is a biochemical process for treating sewage and industrial wastewater that uses air (or oxygen) and microorganisms to biologically oxidize organic pollutants, producing a waste sludge (or floc) containing the oxidized material. In general, an activated sludge process includes:

- An aeration tank where air (or oxygen) is injected and thoroughly mixed into the wastewater.

- A settling tank (usually referred to as a clarifier or "settler") to allow the waste sludge to settle. Part of the waste sludge is recycled to the aeration tank and the remaining waste sludge is removed for further treatment and ultimate disposal.

Trickling filter process

A trickling filter consists of a bed of rocks, gravel, slag, peat moss, or plastic media over which wastewater flows downward and contacts a layer (or film) of microbial slime covering the bed media. Aerobic conditions are maintained by forced air flowing through the bed or by natural convection of air. The process involves adsorption of organic compounds in the wastewater by the microbial slime layer, diffusion of air into the slime layer to provide the oxygen required for the biochemical oxidation of the organic compounds. The end products include carbon dioxide gas, water and other products of the oxidation. As the slime layer thickens, it becomes difficult for the air to penetrate the layer and an inner anaerobic layer is formed.

The fundamental components of a complete trickling filter system are:

- A bed of filter medium upon which a layer of microbial slime is promoted and developed.

- An enclosure or a container which houses the bed of filter medium.

- A system for distributing the flow of wastewater over the filter medium.

- A system for removing and disposing of any sludge from the treated effluent.

The treatment of sewage or other wastewater with trickling filters is among the oldest and most well characterized treatment technologies.

A trickling filter is also often called a trickle filter, trickling biofilter, biofilter, biological filter or biological trickling filter.

Treatment of other organics

Synthetic organic materials including solvents, paints, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, products from coke production and so forth can be very difficult to treat. Treatment methods are often specific to the material being treated. Methods include advanced oxidation processing, distillation, adsorption, vitrification, incineration, chemical immobilisation or landfill disposal. Some materials such as some detergents may be capable of biological degradation and in such cases, a modified form of wastewater treatment can be used.

Treatment of acids and alkalis

Acids and alkalis can usually be neutralised under controlled conditions. Neutralisation frequently produces a precipitate that will require treatment as a solid residue that may also be toxic. In some cases, gases may be evolved requiring treatment for the gas stream. Some other forms of treatment are usually required following neutralisation.

Waste streams rich in hardness ions as from de-ionisation processes can readily lose the hardness ions in a buildup of precipitated calcium and magnesium salts. This precipitation process can cause severe furring of pipes and can, in extreme cases, cause the blockage of disposal pipes. A 1 metre diameter industrial marine discharge pipe serving a major chemicals complex was blocked by such salts in the 1970s. Treatment is by concentration of de-ionisation waste waters and disposal to landfill or by careful pH management of the released wastewater.

Treatment of toxic materials

Toxic materials including many organic materials, metals (such as zinc, silver, cadmium, thallium, etc.) acids, alkalis, non-metallic elements (such as arsenic or selenium) are generally resistant to biological processes unless very dilute. Metals can often be precipitated out by changing the pH or by treatment with other chemicals. Many, however, are resistant to treatment or mitigation and may require concentration followed by landfilling or recycling. Dissolved organics can be incinerated within the wastewater by the advanced oxidation process.

See also

- Best management practice for water pollution (BMP)

- List of waste water treatment technologies

- Purified water (for industrial use)

- Water purification (for drinking water)

References

- ↑ Kashiwaya, Mamoru; Yoshimoto, Kameo (May 1980). "Tannery Wastewater Treatment by the Oxygen Activated Sludge Process". Journal (Water Pollution Control Federation) (Alexandria, VA: Water Environment Federation) 52 (5): 999–1007. JSTOR 25040825.

- 1 2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. "Effluent Limitations Guidelines and Standards for the Steam Electric Power Generating Point Source Category." Final Rule. 2015-09-30.

- ↑ European Environment Agency. Copenhagen, Denmark. "Indicator: Biochemical oxygen demand in rivers (2001)."

- 1 2 Tchobanoglous, G., Burton, F.L., and Stensel, H.D. (2003). Wastewater Engineering (Treatment Disposal Reuse) / Metcalf & Eddy, Inc. (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-041878-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. LCCN 67019834.

- ↑ Hobson, Tom (May 2004). "The Scoop on Oil Skimmers". Environmental Protection (formerly Water and Wastewater News) (Dallas, TX: 1105 Media, Inc.).

- ↑ American Petroleum Institute (API) (February 1990). Management of Water Discharges: Design and Operations of Oil-Water Separators (1st ed.). American Petroleum Institute.

- 1 2 Beychok, Milton R. (December 1971). "Wastewater treatment". Hydrocarbon Processing: 109–112. ISSN 0887-0284.

- ↑ Cleanawater

External links

- Water Environment Federation - Professional society

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||