Laundry

Laundry is the washing of clothing and linens.[1] Laundry processes are often done in a room reserved for that purpose; in an individual home this is referred to as a laundry room or utility room. An apartment building or student hall of residence may have a shared laundry facility such as a tvättstuga. A stand-alone business is referred to as a laundrette (laundromat). The material that is being washed, or has been laundered, is also generally referred to as laundry.

History

Watercourses

Laundry was first done in watercourses, letting the water carry away the materials which could cause stains and smells. Laundry is still done this way in some less industrialized areas and rural regions. Agitation helps remove the dirt, so the laundry is often rubbed, twisted, or slapped against flat rocks. Wooden bats or clubs could be used to help with beating the dirt out. These were often called washing beetles or bats and could be used by the waterside on a rock (a beetling-stone), on a block (battling-block), or on a board. They were once common across Europe and were also used by settlers in North America. Similar techniques have also been identified in Japan.

When no watercourses were available, laundry was done in water-tight vats or vessels. Sometimes large metal cauldrons were filled with fresh water and heated over a fire; boiling water was even more effective than cold in removing dirt. Wooden or stone scrubbing surfaces set up near a water supply or portable washboards, including factory-made corrugated metal ones, gradually replaced rocks as a surface for loosening soil.

A posser could be used to agitate clothes in a tub.[2]

Once clean, the clothes were wrung out — twisted to remove most of the water. Then they were hung up on poles or clotheslines to air dry, or sometimes just spread out on clean grass.

Washhouses

Before the advent of the washing machine, apart from watercourses, laundry was also done in communal or public washhouses (also called wash-houses or wash houses), especially in rural areas in Europe or the Mediterranean Basin. Water was channelled from a river or spring and fed into a building or outbuilding built specifically for laundry purposes and often containing two basins - one for washing and the other for rinsing - through which the water was constantly flowing, as well as a stone lip inclined towards the water against which the washers could beat the clothes. Such facilities were much more comfortable than washing in a watercourse because the launderers could work standing up instead of on their knees, and were protected from inclement weather by walls (often) and a roof (with some exceptions). Also, they didn't have to go far, as the facilities were usually at hand in the village or at the edge of a town. These facilities were public and available to all families, and usually used by the entire village. The laundry job was reserved for women, who washed all their family's laundry (or the laundry of others as a paid job). As such, washhouses were an obligatory stop in many women's weekly lives and became a sort of institution or meeting place for women in towns or villages, where they could discuss issues or simply chat, equated by many with gossip, and equatable to the concept of the village pump in English. Indeed, this tradition is reflected in the Catalan idiom "fer safareig" (literally, "to do the laundry"), which means to gossip, for instance.

Many of these washhouses are still standing and even filled with water in villages throughout Europe. In cities (in Europe as of the 19th century), public washhouses were also built so that the poorer population, who would otherwise not have access to laundry facilities, could wash their clothes. The aim was to foster hygiene and thus reduce outbreaks of epidemics.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution completely transformed laundry technology.

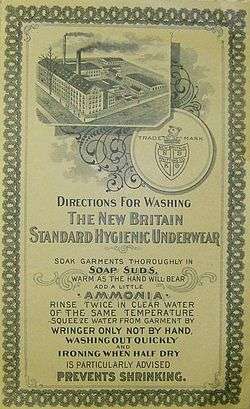

The mangle (or "wringer"in American English) was developed in the 19th century — two long rollers in a frame and a crank to revolve them. A laundry-worker took sopping wet clothing and cranked it through the mangle, compressing the cloth and expelling the excess water. The mangle was much quicker than hand twisting. It was a variation on the box mangle used primarily for pressing and smoothing cloth.

Meanwhile, 19th century inventors further mechanized the laundry process with various hand-operated washing machines. Most involved turning a handle to move paddles inside a tub. Then some early 20th century machines used an electrically powered agitator to replace tedious hand rubbing against a washboard. Many of these were simply a tub on legs, with a hand-operated mangle on top. Later the mangle too was electrically powered, then replaced by a perforated double tub, which spun out the excess water in a spin cycle.

Laundry drying was also mechanized, with clothes dryers. Dryers were also spinning perforated tubs, but they blew heated air rather than water.

Chinese laundries in North America

In the United States and Canada in the late 19th and early 20th century, the occupation of laundry worker was heavily identified with Chinese Americans. Discrimination, lack of English-language skills, and lack of capital kept Chinese Americans out of most desirable careers. Around 1900, one in four ethnic Chinese men in the U.S. worked in a laundry, typically working 10 to 16 hours a day.[3][4]

New York City had an estimated 3,550 Chinese laundries at the beginning of the Great Depression of the 1930s. In 1933, with even this looking to many people like a relatively desirable business, the city's Board of Aldermen passed a law clearly intended to drive the Chinese out of the business. Among other things, it limited ownership of laundries to U.S. citizens. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association tried fruitlessly to fend this off, resulting in the formation of the openly leftist Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance (CHLA), which successfully challenged this provision of the law, allowing Chinese laundry workers to preserve their livelihoods.[3]

The CHLA went on to function as a more general civil rights group; its numbers declined strongly after it was targeted by the FBI during the Second Red Scare (1947–1957).[3]

Laundry processes

Laundry processes include washing (usually with water containing detergents or other chemicals), agitation, rinsing, drying and pressing (ironing). The washing will often be done at a temperature above room temperature to increase the activities of any chemicals used and the solubility of stains, and high temperatures kill micro-organisms that may be present on the fabric.

Chemicals

Various chemicals may be used to increase the solvent power of water, such as the compounds in soaproot or yucca-root used by Native American tribes, or the ash lye once widely used for soaking laundry in Europe. Soap, a compound made from lye and fat, is an ancient and common laundry aid. Modern washing machines typically use synthetic powdered or liquid laundry detergent in place of more traditional soap.

Cleaning or Dry cleaning

Dry cleaning is any cleaning process for clothing and textiles using a chemical solvent other than water.[5] The solvent used is typically tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene), which the industry calls "perc".[6][7] It is used to clean delicate fabrics that cannot withstand the rough and tumble of a washing machine and clothes dryer; it can also obviate labor-intensive hand washing.

Laundry hygiene

For laundry hygiene see under hygiene.

Apartments

In some parts of the world, including North America, apartment buildings and dormitories often have laundry rooms, where residents share washing machines and dryers. Usually the machines are set to run only when money is put in a coin slot.

In other parts of the world, including Europe, apartment buildings with laundry rooms are uncommon, and each apartment may have its own washing machine. Those without a machine at home or the use of a laundry room must either wash their clothes by hand or visit a commercial self-service laundry.

Right to dry movement

Some organizations have been campaigning against legislation which has outlawed line-drying of clothing in public places, especially given the increased greenhouse gas emissions produced by clothes dryers.

Legislation making it possible for thousands of American families to start using clotheslines in communities where they were formerly banned was passed in Colorado in 2008. In 2009, clothesline legislation was debated in the states of Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Maine, New Hampshire, Nebraska, Oregon, Virginia, and Vermont. Other states are considering similar bills.

Many homeowners' associations and other communities in the United States prohibit residents from using a clothesline outdoors, or limit such use to locations that are not visible from the street or to certain times of day. Other communities, however, expressly prohibit rules that prevent the use of clotheslines. Florida is the only state to expressly guarantee a right to dry, although Utah and Hawaii have passed solar rights legislation.

A Florida law explicitly states: "No deed restrictions, covenants, or similar binding agreements running with the land shall prohibit or have the effect of prohibiting solar collectors, clotheslines, or other energy devices based on renewable resources from being installed on buildings erected on the lots or parcels covered by the deed restrictions, covenants, or binding agreements."[8] No other state has such clearcut legislation. Vermont considered a "Right to Dry" bill in 1999, but it was defeated in the Senate Natural Resources & Energy Committee. The language has been included in a 2007 voluntary energy conservation bill, introduced by Senator Dick McCormack. Similar measures have been introduced in Canada, in particular the province of Ontario.

Common problems

Novice users of modern laundry machines sometimes experience accidental shrinkage of garments, especially when applying heat. For wool garments, this is due to scales on the fibers, which heat and agitation cause to stick together. Other fabrics are stretched by mechanical forces during production, and can shrink slightly when heated (though to a lesser degree than wool). Some clothes are "pre-shrunk" to avoid this problem.[9]

Another common problem is color bleeding. For example, washing a red shirt with white underwear can result in pink underwear. Often only like colors are washed together to avoid this problem, which is lessened by cold water and repeated washings.

Laundry symbols are included on many clothes to help consumers avoid these problems.

Etymology

The word laundry comes from Middle English lavendrye, laundry, from Old French lavanderie, from lavandier.[1]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Laundry". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ↑ "Ponch, punch or ?". OldandInteresting.com. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- 1 2 3 "Yung, Judy; Chang, Gordon H.; Lai, Him Mark, eds. (2006), "Declaration of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance.", Chinese American Voices, University of California Press, pp. 183–185 (including notes), ISBN 0-520-24310-2

- ↑ Ban Seng Hoe (2004), Enduring Hardship: The Chinese Laundry in Canada, Canadian Museum of Civilization, ISBN 0-660-19078-8

- ↑ "How Does The Dry Cleaning Process Work?". LX. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

Dry cleaning is the process of deep cleaning clothing without using water. Usually reserved for dress clothes and delicate fabric, it requires special equipment and detergents. Dry cleaning is typically a 5 step process. These steps are tagging the clothes, pretreating clothes, cleaning, quality checking, and ironing.

- ↑ "Toxic Substances Portal - Tetrachloroethylene (PERC)". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Tetrachloroethylene (Perchloroethylene)". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "The 2008 Florida Statutes". 163.04. Florida Senate. 2008.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ "Why Clothes Shrink".

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

_-_n._12182_-_Sanremo_-_Popolane_al_lavatojo.jpg)