Electromagnetic induction

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

|

Electromagnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force across a conductor exposed to time varying magnetic fields. Michael Faraday, who mathematically described Faraday's law of induction, is generally credited with its discovery in 1831.

History

Electromagnetic induction was first discovered by Michael Faraday, who made his discovery public in 1831.[2][3] It was discovered independently by Joseph Henry in 1832.[4][5]

In Faraday's first experimental demonstration (August 29, 1831), he wrapped two wires around opposite sides of an iron ring or "torus" (an arrangement similar to a modern toroidal transformer). [6] Based on his assessment of recently discovered properties of electromagnets, he expected that, when current started to flow in one wire, a sort of wave would travel through the ring and cause some electrical effect on the opposite side. He plugged one wire into a galvanometer, and watched it as he connected the other wire to a battery. Indeed, he saw a transient current (which he called a "wave of electricity") when he connected the wire to the battery, and another when he disconnected it.[7] This induction was due to the change in magnetic flux that occurred when the battery was connected and disconnected.[1] Within two months, Faraday found several other manifestations of electromagnetic induction. For example, he saw transient currents when he quickly slid a bar magnet in and out of a coil of wires, and he generated a steady (DC) current by rotating a copper disk near the bar magnet with a sliding electrical lead ("Faraday's disk").[8]

Faraday explained electromagnetic induction using a concept he called lines of force. However, scientists at the time widely rejected his theoretical ideas, mainly because they were not formulated mathematically.[9] An exception was James Clerk Maxwell, who used Faraday's ideas as the basis of his quantitative electromagnetic theory.[9][10][11] In Maxwell's model, the time varying aspect of electromagnetic induction is expressed as a differential equation, which Oliver Heaviside referred to as Faraday's law even though it is slightly different from Faraday's original formulation and does not describe motional EMF. Heaviside's version (see Maxwell–Faraday equation below) is the form recognized today in the group of equations known as Maxwell's equations.

Heinrich Lenz formulated the law named after him in 1834 to describe the "flux through the circuit". Lenz's law gives the direction of the induced EMF and current resulting from electromagnetic induction (elaborated upon in the examples below).

Following the understanding brought by these laws, many kinds of device employing magnetic induction have been invented.

Theory

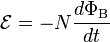

The law of physics describing the process of electromagnetic induction is known as Faraday's law of induction and the most widespread version of this law states that the induced electromotive force in any closed circuit is equal to the rate of change of the magnetic flux enclosed by the circuit.[13][14] Or mathematically,

,

,

where  is the electromotive force (EMF) and ΦB is the magnetic flux. The direction of the electromotive force is given by Lenz's law. This version of Faraday's law strictly holds only when the closed circuit is a loop of infinitely thin wire,[15] and is invalid in some other circumstances. A different version, the Maxwell–Faraday equation (discussed below), is valid in all circumstances.

is the electromotive force (EMF) and ΦB is the magnetic flux. The direction of the electromotive force is given by Lenz's law. This version of Faraday's law strictly holds only when the closed circuit is a loop of infinitely thin wire,[15] and is invalid in some other circumstances. A different version, the Maxwell–Faraday equation (discussed below), is valid in all circumstances.

For a tightly wound coil of wire, composed of N identical turns, each with the same magnetic flux going through them, the resulting EMF is given by[16][17]

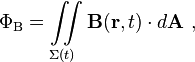

Faraday's law of induction makes use of the magnetic flux ΦB through a hypothetical surface Σ whose boundary is a wire loop. Since the wire loop may be moving, we write Σ(t) for the surface. The magnetic flux is defined by a surface integral:

where dA is an element of surface area of the moving surface Σ(t), B is the magnetic field, and B·dA is a vector dot product (the infinitesimal amount of magnetic flux). In more visual terms, the magnetic flux through the wire loop is proportional to the number of magnetic flux lines that pass through the loop.

When the flux changes—because B changes, or because the wire loop is moved or deformed, or both—Faraday's law of induction says that the wire loop acquires an EMF,  , defined as the energy available from a unit charge that has travelled once around the wire loop.[15][18][19][20] Equivalently, it is the voltage that would be measured by cutting the wire to create an open circuit, and attaching a voltmeter to the leads.

, defined as the energy available from a unit charge that has travelled once around the wire loop.[15][18][19][20] Equivalently, it is the voltage that would be measured by cutting the wire to create an open circuit, and attaching a voltmeter to the leads.

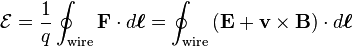

According to the Lorentz force law (in SI units),

the EMF on a wire loop is:

where E is the electric field, B is the magnetic field (aka magnetic flux density, magnetic induction), dℓ is an infinitesimal arc length along the wire, and the line integral is evaluated along the wire (along the curve coincident with the shape of the wire).

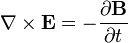

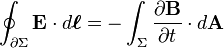

Maxwell–Faraday equation

The Maxwell–Faraday equation is a generalisation of Faraday's law that states that a time-varying magnetic field is always accompanied by a spatially-varying, non-conservative electric field, and vice versa. The Maxwell–Faraday equation is

(in SI units) where  is the curl operator and again E(r, t) is the electric field and B(r, t) is the magnetic field. These fields can generally be functions of position r and time t.

is the curl operator and again E(r, t) is the electric field and B(r, t) is the magnetic field. These fields can generally be functions of position r and time t.

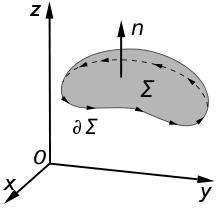

The Maxwell–Faraday equation is one of the four Maxwell's equations, and therefore plays a fundamental role in the theory of classical electromagnetism. It can also be written in an integral form by the Kelvin-Stokes theorem:[21]

where, as indicated in the figure:

- Σ is a surface bounded by the closed contour ∂Σ,

- E is the electric field, B is the magnetic field.

- dℓ is an infinitesimal vector element of the contour ∂Σ,

- dA is an infinitesimal vector element of surface Σ. If its direction is orthogonal to that surface patch, the magnitude is the area of an infinitesimal patch of surface.

Both dℓ and dA have a sign ambiguity; to get the correct sign, the right-hand rule is used, as explained in the article Kelvin-Stokes theorem. For a planar surface Σ, a positive path element dℓ of curve ∂Σ is defined by the right-hand rule as one that points with the fingers of the right hand when the thumb points in the direction of the normal n to the surface Σ.

The integral around ∂Σ is called a path integral or line integral.

Applications

The principles of electromagnetic induction are applied in many devices and systems, including:

- Current clamp

- Electrical generators

- Electromagnetic forming

- Graphics tablet

- Hall effect meters

- Induction cookers

- Induction motors

- Induction sealing

- Induction welding

- Inductive charging

- Inductors

- Magnetic flow meters

- Mechanically powered flashlight

- Pickups

- Rowland ring

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- Transformers

- Wireless energy transfer

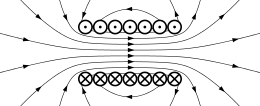

Electrical generator

The EMF generated by Faraday's law of induction due to relative movement of a circuit and a magnetic field is the phenomenon underlying electrical generators. When a permanent magnet is moved relative to a conductor, or vice versa, an electromotive force is created. If the wire is connected through an electrical load, current will flow, and thus electrical energy is generated, converting the mechanical energy of motion to electrical energy. For example, the drum generator is based upon the figure to the right. A different implementation of this idea is the Faraday's disc, shown in simplified form on the right.

In the Faraday's disc example, the disc is rotated in a uniform magnetic field perpendicular to the disc, causing a current to flow in the radial arm due to the Lorentz force. It is interesting to understand how it arises that mechanical work is necessary to drive this current. When the generated current flows through the conducting rim, a magnetic field is generated by this current through Ampère's circuital law (labeled "induced B" in the figure). The rim thus becomes an electromagnet that resists rotation of the disc (an example of Lenz's law). On the far side of the figure, the return current flows from the rotating arm through the far side of the rim to the bottom brush. The B-field induced by this return current opposes the applied B-field, tending to decrease the flux through that side of the circuit, opposing the increase in flux due to rotation. On the near side of the figure, the return current flows from the rotating arm through the near side of the rim to the bottom brush. The induced B-field increases the flux on this side of the circuit, opposing the decrease in flux due to rotation. Thus, both sides of the circuit generate an EMF opposing the rotation. The energy required to keep the disc moving, despite this reactive force, is exactly equal to the electrical energy generated (plus energy wasted due to friction, Joule heating, and other inefficiencies). This behavior is common to all generators converting mechanical energy to electrical energy.

Electrical transformer

When the electric current in a loop of wire changes, the changing current creates a changing magnetic field. A second wire in reach of this magnetic field will experience this change in magnetic field as a change in its coupled magnetic flux, d ΦB / d t. Therefore, an electromotive force is set up in the second loop called the induced EMF or transformer EMF. If the two ends of this loop are connected through an electrical load, current will flow.

Magnetic flow meter

Faraday's law is used for measuring the flow of electrically conductive liquids and slurries. Such instruments are called magnetic flow meters. The induced voltage ℇ generated in the magnetic field B due to a conductive liquid moving at velocity v is thus given by:

where ℓ is the distance between electrodes in the magnetic flow meter.

Eddy currents

Conductors (of finite dimensions) moving through a uniform magnetic field, or stationary within a changing magnetic field, will have currents induced within them. These induced eddy currents can be undesirable, since they dissipate energy in the resistance of the conductor. There are a number of methods employed to control these undesirable inductive effects.

- Electromagnets in electric motors, generators, and transformers do not use solid metal, but instead use thin sheets of metal plate, called laminations. These thin plates reduce the parasitic eddy currents, as described below.

- Inductive coils in electronics typically use magnetic cores to minimize parasitic current flow. They are a mixture of metal powder plus a resin binder that can hold any shape. The binder prevents parasitic current flow through the powdered metal.

Electromagnet laminations

Eddy currents occur when a solid metallic mass is rotated in a magnetic field, because the outer portion of the metal cuts more lines of force than the inner portion, hence the induced electromotive force not being uniform, tends to set up currents between the points of greatest and least potential. Eddy currents consume a considerable amount of energy and often cause a harmful rise in temperature.[22]

Only five laminations or plates are shown in this example, so as to show the subdivision of the eddy currents. In practical use, the number of laminations or punchings ranges from 40 to 66 per inch, and brings the eddy current loss down to about one percent. While the plates can be separated by insulation, the voltage is so low that the natural rust/oxide coating of the plates is enough to prevent current flow across the laminations.[22]

This is a rotor approximately 20mm in diameter from a DC motor used in a CD player. Note the laminations of the electromagnet pole pieces, used to limit parasitic inductive losses.

Parasitic induction within inductors

In this illustration, a solid copper bar inductor on a rotating armature is just passing under the tip of the pole piece N of the field magnet. Note the uneven distribution of the lines of force across the bar inductor. The magnetic field is more concentrated and thus stronger on the left edge of the copper bar (a,b) while the field is weaker on the right edge (c,d). Since the two edges of the bar move with the same velocity, this difference in field strength across the bar creates whorls or current eddies within the copper bar.[23]

High current power-frequency devices, such as electric motors, generators and transformers, use multiple small conductors in parallel to break up the eddy flows that can form within large solid conductors. The same principle is applied to transformers used at higher than power frequency, for example, those used in switch-mode power supplies and the intermediate frequency coupling transformers of radio receivers.

See also

References

- 1 2 Giancoli, Douglas C. (1998). Physics: Principles with Applications (Fifth ed.). pp. 623–624.

- ↑ Ulaby, Fawwaz (2007). Fundamentals of applied electromagnetics (5th ed.). Pearson:Prentice Hall. p. 255. ISBN 0-13-241326-4.

- ↑ "Joseph Henry". Distinguished Members Gallery, National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Electromagnetism" (PDF).

- ↑ "Electromagnetism". Smithsonian Institution Archives.

- ↑ Faraday, Michael; Day, P. (1999-02-01). The philosopher's tree: a selection of Michael Faraday's writings. CRC Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7503-0570-9. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ↑ Michael Faraday, by L. Pearce Williams, p. 182-3

- ↑ Michael Faraday, by L. Pearce Williams, p. 191–5

- 1 2 Michael Faraday, by L. Pearce Williams, p. 510

- ↑ Maxwell, James Clerk (1904), A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, Vol. II, Third Edition. Oxford University Press, pp. 178–9 and 189.

- ↑ "Archives Biographies: Michael Faraday", The Institution of Engineering and Technology.

- ↑ Poyser, Arthur William (1892), Magnetism and electricity: A manual for students in advanced classes. London and New York; Longmans, Green, & Co., p. 285, fig. 248. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ "Faraday's Law, which states that the electromotive force around a closed path is equal to the negative of the time rate of change of magnetic flux enclosed by the path"Jordan, Edward; Balmain, Keith G. (1968). Electromagnetic Waves and Radiating Systems (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 100.

- ↑ "The magnetic flux is that flux which passes through any and every surface whose perimeter is the closed path"Hayt, William (1989). Engineering Electromagnetics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 312. ISBN 0-07-027406-1.

- 1 2 "The flux rule" is the terminology that Feynman uses to refer to the law relating magnetic flux to EMF.Richard Phillips Feynman, Leighton R B & Sands M L (2006). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. San Francisco: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. Vol. II, pp. 17-2. ISBN 0-8053-9049-9.

- ↑ Essential Principles of Physics, P.M. Whelan, M.J. Hodgeson, 2nd Edition, 1978, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-3382-1

- ↑ Nave, Carl R. "Faraday's Law". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (Third ed.). Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 301–303. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- ↑ Tipler and Mosca, Physics for Scientists and Engineers, p 795, google books link

- ↑ Note that different textbooks may give different definitions. The set of equations used throughout the text was chosen to be compatible with the special relativity theory.

- ↑ Roger F Harrington (2003). Introduction to electromagnetic engineering. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 56. ISBN 0-486-43241-6.

- 1 2 Images and reference text are from the public domain book: Hawkins Electrical Guide, Volume 1, Chapter 19: Theory of the Armature, pp. 272–273, Copyright 1917 by Theo. Audel & Co., Printed in the United States

- ↑ Images and reference text are from the public domain book: Hawkins Electrical Guide, Volume 1, Chapter 19: Theory of the Armature, pp. 270–271, Copyright 1917 by Theo. Audel & Co., Printed in the United States

Further reading

- Maxwell, James Clerk (1881), A treatise on electricity and magnetism, Vol. II, Chapter III, §530, p. 178. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-486-60637-6.

External links

- Magnet academy

- A simple interactive Java tutorial on electromagnetic induction National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- R. Vega Induction: Faraday's law and Lenz's law - Highly animated lecture

- Faraday's Law for EMC Engineers

- Tankersley and Mosca: Introducing Faraday's law

- A free java simulation on motional EMF

|