Index of coincidence

In cryptography, coincidence counting is the technique (invented by William F. Friedman[1]) of putting two texts side-by-side and counting the number of times that identical letters appear in the same position in both texts. This count, either as a ratio of the total or normalized by dividing by the expected count for a random source model, is known as the index of coincidence, or IC for short.

Calculation

The index of coincidence provides a measure of how likely it is to draw two matching letters by randomly selecting two letters from a given text. The chance of drawing a given letter in the text is (number of times that letter appears / length of the text). The chance of drawing that same letter again (without replacement) is (appearances - 1 / text length - 1). The product of these two values gives you the chance of drawing that letter twice in a row. One can find this product for each letter that appears in the text, then sum these products to get a chance of drawing two of a kind. This probability can then be normalized by multiplying it by some coefficient, typically 26 in English.

- Where c is the normalizing coefficient (26 for English), na is the number of times the letter "a" appears in the text, and N is the length of the text.

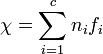

We can express the index of coincidence IC for a given letter-frequency distribution as a summation:

where N is the length of the text and n1 through nc are the frequencies (as integers) of the c letters of the alphabet (c = 26 for monocase English). The sum of the ni is necessarily N.

The products n(n−1) count the number of combinations of n elements taken two at a time. (Actually this counts each pair twice; the extra factors of 2 occur in both numerator and denominator of the formula and thus cancel out.) Each of the ni occurrences of the i-th letter matches each of the remaining ni−1 occurrences of the same letter. There are a total of N(N−1) letter pairs in the entire text, and 1/c is the probability of a match for each pair, assuming a uniform random distribution of the characters (the "null model"; see below). Thus, this formula gives the ratio of the total number of coincidences observed to the total number of coincidences that one would expect from the null model.[2]

The expected average value for the IC can be computed from the relative letter frequencies fi of the source language:

If all c letters of an alphabet were equally distributed, the expected index would be 1.0. The actual monographic IC for telegraphic English text is around 1.73, reflecting the unevenness of natural-language letter distributions.

Sometimes values are reported without the normalizing denominator, for example 0.067=1.73/26 for English; such values may be called κp ("kappa-plaintext") rather than IC, with κr ("kappa-random") used to denote the denominator 1/c (which is the expected coincidence rate for a uniform distribution of the same alphabet, 0.0385=1/26 for English).

Application

The index of coincidence is useful both in the analysis of natural-language plaintext and in the analysis of ciphertext (cryptanalysis). Even when only ciphertext is available for testing and plaintext letter identities are disguised, coincidences in ciphertext can be caused by coincidences in the underlying plaintext. This technique is used to cryptanalyze the Vigenère cipher, for example. For a repeating-key polyalphabetic cipher arranged into a matrix, the coincidence rate within each column will usually be highest when the width of the matrix is a multiple of the key length, and this fact can be used to determine the key length, which is the first step in cracking the system.

Coincidence counting can help determine when two texts are written in the same language using the same alphabet. (This technique has been used to examine the purported Bible code). The causal coincidence count for such texts will be distinctly higher than the accidental coincidence count for texts in different languages, or texts using different alphabets, or gibberish texts.

To see why, imagine an "alphabet" of only the two letters A and B. Suppose that in our "language", the letter A is used 75% of the time, and the letter B is used 25% of the time. If two texts in this language are laid side by side, then the following pairs can be expected:

| Pair | Probability |

|---|---|

| AA | 56.25% |

| BB | 6.25% |

| AB | 18.75% |

| BA | 18.75% |

Overall, the probability of a "coincidence" is 62.5% (56.25% for AA + 6.25% for BB).

Now consider the case when both messages are encrypted using the simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher which replaces A with B and vice versa:

| Pair | Probability |

|---|---|

| AA | 6.25% |

| BB | 56.25% |

| AB | 18.75% |

| BA | 18.75% |

The overall probability of a coincidence in this situation is 62.5% (6.25% for AA + 56.25% for BB), exactly the same as for the unencrypted "plaintext" case. In effect, the new alphabet produced by the substitution is just a uniform renaming of the original character identities, which does not affect whether they match.

Now suppose that only one message (say, the second) is encrypted using the same substitution cipher (A,B)→(B,A). The following pairs can now be expected:

| Pair | Probability |

|---|---|

| AA | 18.75% |

| BB | 18.75% |

| AB | 56.25% |

| BA | 6.25% |

Now the probability of a coincidence is only 37.5% (18.75% for AA + 18.75% for BB). This is noticeably lower than the probability when same-language, same-alphabet texts were used. Evidently, coincidences are more likely when the most frequent letters in each text are the same.

The same principle applies to real languages like English, because certain letters, like E, occur much more frequently than other letters—a fact which is used in frequency analysis of substitution ciphers. Coincidences involving the letter E, for example, are relatively likely. So when any two English texts are compared, the coincidence count will be higher than when an English text and a foreign-language text are used.

It can easily be imagined that this effect can be subtle. For example, similar languages will have a higher coincidence count than dissimilar languages. Also, it isn't hard to generate random text with a frequency distribution similar to real text, artificially raising the coincidence count. Nevertheless, this technique can be used effectively to identify when two texts are likely to contain meaningful information in the same language using the same alphabet, to discover periods for repeating keys, and to uncover many other kinds of nonrandom phenomena within or among ciphertexts.

Expected values for various languages[3] are:

| Language | Index of Coincidence |

|---|---|

| English | 1.73 |

| French | 2.02 |

| German | 2.05 |

| Italian | 1.94 |

| Portuguese | 1.94 |

| Russian | 1.76 |

| Spanish | 1.94 |

Generalization

The above description is only an introduction to use of the index of coincidence, which is related to the general concept of correlation. Various forms of Index of Coincidence have been devised; the "delta" I.C. (given by the formula above) in effect measures the autocorrelation of a single distribution, whereas a "kappa" I.C. is used when matching two text strings.[4] Although in some applications constant factors such as  and

and  can be ignored, in more general situations there is considerable value in truly indexing each I.C. against the value to be expected for the null hypothesis (usually: no match and a uniform random symbol distribution), so that in every situation the expected value for no correlation is 1.0. Thus, any form of I.C. can be expressed as the ratio of the number of coincidences actually observed to the number of coincidences expected (according to the null model), using the particular test setup.

can be ignored, in more general situations there is considerable value in truly indexing each I.C. against the value to be expected for the null hypothesis (usually: no match and a uniform random symbol distribution), so that in every situation the expected value for no correlation is 1.0. Thus, any form of I.C. can be expressed as the ratio of the number of coincidences actually observed to the number of coincidences expected (according to the null model), using the particular test setup.

From the foregoing, it is easy to see that the formula for kappa I.C.' is

where  is the common aligned length of the two texts A and B, and the bracketed term is defined as 1 if the

is the common aligned length of the two texts A and B, and the bracketed term is defined as 1 if the  -th letter of text A matches the

-th letter of text A matches the  -th letter of text B, otherwise 0.

-th letter of text B, otherwise 0.

A related concept, the "bulge" of a distribution, measures the discrepancy between the observed I.C. and the null value of 1.0. The number of cipher alphabets used in a polyalphabetic cipher may be estimated by dividing the expected bulge of the delta I.C. for a single alphabet by the observed bulge for the message, although in many cases (such as when a repeating key was used) better techniques are available.

Example

As a practical illustration of the use of I.C., suppose that we have intercepted the following ciphertext message:

QPWKA LVRXC QZIKG RBPFA EOMFL JMSDZ VDHXC XJYEB IMTRQ WNMEA

IZRVK CVKVL XNEIC FZPZC ZZHKM LVZVZ IZRRQ WDKEC HOSNY XXLSP

MYKVQ XJTDC IOMEE XDQVS RXLRL KZHOV

(The grouping into five characters is just a telegraphic convention and has nothing to do with actual word lengths.) Suspecting this to be an English plaintext encrypted using a Vigenère cipher with normal A–Z components and a short repeating keyword, we can consider the ciphertext "stacked" into some number of columns, for example seven:

QPWKALV

RXCQZIK

GRBPFAE

OMFLJMS

DZVDHXC

XJYEBIM

TRQWN…

If the key size happens to have been the same as the assumed number of columns, then all the letters within a single column will have been enciphered using the same key letter, in effect a simple Caesar cipher applied to a random selection of English plaintext characters. The corresponding set of ciphertext letters should have a roughness of frequency distribution similar to that of English, although the letter identities have been permuted (shifted by a constant amount corresponding to the key letter). Therefore, if we compute the aggregate delta I.C. for all columns ("delta bar"), it should be around 1.73. On the other hand, if we have incorrectly guessed the key size (number of columns), the aggregate delta I.C. should be around 1.00. So we compute the delta I.C. for assumed key sizes from one to ten:

| Size | Delta-bar I.C. |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.12 |

| 2 | 1.19 |

| 3 | 1.05 |

| 4 | 1.17 |

| 5 | 1.82 |

| 6 | 0.99 |

| 7 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 1.05 |

| 9 | 1.16 |

| 10 | 2.07 |

We see that the key size is most likely five. If the actual size is five, we would expect a width of ten to also report a high I.C., since each of its columns also corresponds to a simple Caesar encipherment, and we confirm this. So we should stack the ciphertext into five columns:

QPWKA

LVRXC

QZIKG

RBPFA

EOMFL

JMSDZ

VDH…

We can now try to determine the most likely key letter for each column considered separately, by performing trial Caesar decryption of the entire column for each of the 26 possibilities A–Z for the key letter, and choosing the key letter that produces the highest correlation between the decrypted column letter frequencies and the relative letter frequencies for normal English text. That correlation, which we don't need to worry about normalizing, can be readily computed as

where  are the observed column letter frequencies and

are the observed column letter frequencies and  are the relative letter frequencies for English.

When we try this, the best-fit key letters are reported to be "

are the relative letter frequencies for English.

When we try this, the best-fit key letters are reported to be "EVERY," which we recognize as an actual word, and using that for Vigenère decryption produces the plaintext:

MUSTC HANGE MEETI NGLOC ATION FROMB RIDGE TOUND ERPAS

SSINC EENEM YAGEN TSARE BELIE VEDTO HAVEB EENAS SIGNE

DTOWA TCHBR IDGES TOPME ETING TIMEU NCHAN GEDXX

from which one obtains:

MUST CHANGE MEETING LOCATION FROM BRIDGE TO UNDERPASS

SINCE ENEMY AGENTS ARE BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN ASSIGNED

TO WATCH BRIDGE STOP MEETING TIME UNCHANGED XX

after word divisions have been restored at the obvious positions. "XX" are evidently "null" characters used to pad out the final group for transmission.

This entire procedure could easily be packaged into an automated algorithm for breaking such ciphers. Due to normal statistical fluctuation, such an algorithm will occasionally make wrong choices, especially when analyzing short ciphertext messages.

References

- ↑ Friedman, W.F. (1922). "The index of coincidence and its applications in cryptology". Department of Ciphers. Publ 22. Geneva, Illinois, USA: Riverbank Laboratories. OCLC 55786052. The original application ignored normalization.

- ↑ Mountjoy, Marjorie (1963). "The Bar Statistics". NSA Technical Journal VII (2,4). Published in two parts.

- ↑ Friedman, W.F. and Callimahos, L.D. (1985) [1956]. Military Cryptanalytics, Part I – Volume 2. Reprinted by Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-074-3.

- ↑ Kahn, David (1996) [1967]. The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\mathbf{IC} = \frac{\displaystyle\sum_{j=1}^{N}[a_j=b_j]}{N/c},](../I/m/f7ce27c5c7f47ae6507cda25c969a179.png)