History of Bangladesh

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bangladesh |

.jpg) |

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Modern

|

|

Related articles |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

Rice Bread Fish Sweets Snacks Sauce |

| Religion |

|

Architects Painters Sculptor |

|

Literature History Genres Institutions Awards Writers |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Monuments |

|

Modern Bangladesh emerged as an independent nation in 1971 after achieving independence from Pakistan in the Bangladesh Liberation War. The country's borders coincide with the major portion of the ancient and historic region of Bengal in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, where civilization dates back over four millennia, to the Copper Age. The history of the region is closely intertwined with the history of Bengal and the history of India.

The area's early history featured a succession of Indian empires, internal squabbling, and a tussle between Hinduism and Buddhism for dominance. Islam became dominant in the 13th century when Sunni missionaries arrived. Later, Muslim rulers reinforced the process of conversion by building masaajid (mosques), and madrassas.

The borders of modern Bangladesh were established with the partition of Bengal and India in August 1947, when the region became East Pakistan as a part of the newly formed State of Pakistan following the Radcliffe Line.[1] However, it was separated from West Pakistan by 1,600 km (994 mi) of Indian territory. Due to political exclusion, ethnic and linguistic discrimination, as well as economic neglect by the politically dominant western-wing, popular agitation and civil disobedience led to the war of independence in 1971. After independence, the new state endured famine, natural disasters and widespread poverty, as well as political turmoil and military coups. The restoration of democracy in 1991 has been followed by relative calm and economic progress.

Etymology of Bengal

The exact origin of the word Bangla or Bengal is unknown. According to Mahabharata, Purana, Harivamsha Vanga was one of the adopted sons of King Vali who founded the Vanga Kingdom.[2] The earliest reference to "Vangala" (Bôngal) has been traced in the Nesari plates (805 AD) of the south Indian ruler Rashtrakuta Govinda III, who invaded northern India in the 9th century,[3] which speak of Dharmapala as the king of Vangala. The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, speak of Govindachandra as the ruler of Vangaladesa.[4][5][6] Shams-ud-din Ilyas Shah took the title "Shah-e-Bangalah" and united the whole region under one government for the first time.[7]

The Vanga Kingdom (also known as Banga) was located in the eastern part of the Indian Subcontinent, comprising part of West Bengal, India and present-day modern Bangladesh. Vanga and Pundra were two dominant tribes in Bangladesh in ancient time.

Ancient period

Pre-historic Bengal

Many of archeological excavations in Bangladesh revealed evidences of the Northern Black Polished Ware culture (abbreviated NBPW or NBP) of the Indian Subcontinent (c. 700–200 BC) which was an Iron Age culture developed beginning around 700 BC and peaked from c. 500–300 BC, coinciding with the emerging of 16 great states or mahajanapadas in Northern India, and the subsequent rise of the Mauryan Empire.[8][9] The eastern part of ancient India, covering much of current days Bangladesh was part of one of such mahajanapadas, the ancient kingdom of Anga,[10] which flourished in the 6th century BCE.[11]

Linguistically, the oldest population of this land may have been speakers of Dravidian languages, such as the Kurux, or perhaps of Austroasiatic languages such as the Santals. Subsequently, people speaking languages from other language families, such as Tibeto-Burman, settled in Bengal. Indic Bengali represents the latest settlement.

While western Bangladesh, as part of Magadha, became part of the Indo-Aryan civilization by the 7th century BCE, the Nanda Dynasty was the first historical state to unify all of Bangladesh under Indo-Aryan rule. Later after the rise of Buddhism many missionaries settled in the land to spread the religion and established many monuments such as Mahasthangarh.

Overseas Colonization

The Vanga Kingdom was a powerful seafaring nation of Ancient India. They had overseas trade relations with Java, Sumatra and Siam (modern day Thailand). According to Mahavamsa, the Vanga prince Vijaya Singha conquered Lanka (modern day Sri Lanka) in 544 BC and gave the name "Sinhala" to the country. Bengali people migrated to the Maritime Southeast Asia and Siam (in modern Thailand), establishing their own colonies there.[7]

Gangaridai Empire

Though north and west Bengal were part of the empire southern Bengal thrived and became powerful with her overseas trades. In 326 BCE, with the invasion of Alexander the Great the region again came to prominence. The Greek and Latin historians suggested that Alexander the Great withdrew from India anticipating the valiant counterattack of the mighty Gangaridai empire that was located in the Bengal region. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer, Coenus, was convinced that it was better to return. Diodorus Siculus mentions Gangaridai to be the most powerful empire in India whose king possessed an army of 20,000 horses, 200,000 infantry, 2,000 chariots and 4,000 elephants trained and equipped for war. The allied forces of Gangaridai Empire and Nanda Empire (Prasii) were preparing a massive counterattack against the forces of Alexander on the banks of Ganges. Gangaridai, according to the Greek accounts, kept on flourishing at least up to the 1st century AD.

Early Middle Ages

The pre-Gupta period of Bengal is shrouded with obscurity. Before the conquest of Samudragupta Bengal was divided into two kingdoms: Pushkarana and Samatata. Chandragupta II had defeated a confederacy of Vanga kings resulting in Bengal becoming part of the Gupta Empire.

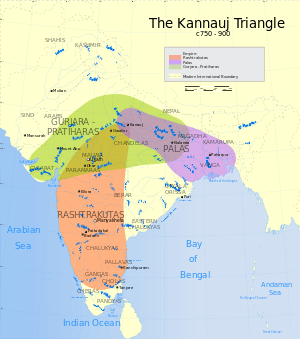

The Pala dynasty

Pala dynasty were the first independent Buddhist dynasty of Bengal. The name Pala (Bengali: পাল pal) means protector and was used as an ending to the names of all Pala monarchs. The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism. Gopala was the first ruler from the dynasty. He came to power in 750 in Gaur, after being elected by a group of feudal chiefs.[12][13] He reigned from 750 to 770 and consolidated his position by extending his control over all of Bengal. The Buddhist dynasty lasted for four centuries (750-1120 AD) and ushered in a period of stability and prosperity in Bengal. They created many temples and works of art as well as supported the Universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila. Somapura Mahavihara built by Dharmapala is the greatest Buddhist Vihara in the Indian Subcontinent.

The empire reached its peak under Dharmapala and Devapala. Dharmapala extended the empire into the northern parts of the Indian Subcontinent. This triggered once more for the control of the subcontinent. Devapala, successor of Dharmapala, expanded the empire considerably. The Pala inscriptions credit him with extensive conquests in hyperbolic language. The Badal pillar inscription of his successor Narayana Pala states that he became the suzerain monarch or Chakravarti of the whole tract of Northern India bounded by the Vindhyas and the Himalayas. It also states that his empire extended up to the two oceans (presumably the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal). It also claims that Devpala defeated Utkala (present-day Orissa), the Hunas, the Dravidas, the Kamarupa (present-day Assam), the Kambojas and the Gurjaras.[14] These claims about Devapala's victories are exaggerated, but cannot be dismissed entirely: there is no reason to doubt his conquest of Utkala and Kamarupa. Besides, the neighbouring kingdoms of Rashtrakutas and the Gurjara-Pratiharas were weak at the time, which might have helped him extend his empire.[15] Devapala is also believed to have led an army up to the Indus river in Punjab.[14]

The death of Devapala ended the period of ascendancy of the Pala Empire and several independent dynasties and kingdoms emerged during this time. However, Mahipala − I rejuvenated the reign of the Palas. He recovered control over all of Bengal and expanded the empire. He survived the invasions of Rajendra Chola of the Chola dynasty and the Western Chalukya Empire from southern India. After Mahipala − I the Pala dynasty again saw its decline until Ramapala, the last great ruler of the dynasty, managed to retrieve the position of the dynasty to some extent. He crushed the Varendra rebellion and extended his empire farther to Kamarupa, Odisha and northern India.

The Pala Empire can be considered as the golden era of Bengal. Never had the Bengali people reached such height of power and glory to that extent. Palas were responsible for the introduction of Mahayana Buddhism in Tibet, Bhutan and Myanmar. The Pala had extensive trade as well as influence in south-east Asia. This can be seen in the sculptures and architectural style of the Sailendra Empire (present-day Malaya, Java, Sumatra).

During the later part of Pala rule, Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire frequently invaded Bengal from 1021 to 1023 CE in order to get Ganges water and in the process, succeeded to humble the rulers, acquiring considerable booty.[16][16] The rulers of Bengal who were defeated by Rajendra Chola were Dharmapal, Ranasur and Govindachandra of the Candra Dynasty who might have been feudatories under Mahipala of the Pala Dynasty.[16] The invasion of the south Indian ruler Vikramaditya VI of the Western Chalukya Empire brought bodies of his countrymen from Karnataka into Bengal which explains the southern origin of the Sena Dynasty.[17] The invasions of the Chola dynasty and Western Chalukya Empire led to the decline of the Pala Dynasty in Bengal and to the establishment of the Sena dynasty

Candra Dynasty

The Candra dynasty were a family who ruled over the kingdom of Harikela in eastern Bengal (comprising the ancient lands of Harikela, Vanga and Samatata) for roughly a century and a half from the beginning of the 10th century CE. Their empire also encompassed Vanga and Samatata, with Srichandra expanding his domain to include parts of Kamarupa. Their empire was ruled from their capital, Vikrampur (modern Munshiganj) and was powerful enough to militarily withstand the Pala Empire to the north-west. The last ruler of the Candra Dynasty Govindachandra was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty in the 11th century.[18]

Sena dynasty

The Palas were followed by the Sena dynasty who brought Bengal under one ruler during the 12th century. Vijay Sen the second ruler of this dynasty defeated the last Pala emperor Madanapala and established his reign. Ballal Sena introduced caste system in Bengal and made Nabadwip the capital. The fourth king of this dynasty Lakshman Sen expanded the empire beyond Bengal to Bihar. Lakshman fled to eastern Bengal under the onslaught of the Muslims without facing them in battle. The Sena dynasty brought a period of revival in Hinduism in Bengal. A popular myth comprehended by some Bengali authors about Jayadeva, the famous Sanskrit poet of Odisha (then known as the Kalinga) and author of Gita Govinda, was one of the Pancharatnas (meaning 5 gems) in the court of Lakshman Sen (although this may be disputed by some).

Deva Kingdom

The Deva Kingdom was a Hindu dynasty of medieval Bengal that ruled over eastern Bengal after the collapse Sena Empire. The capital of this dynasty was Bikrampur in present-day Munshiganj District of Bangladesh. The inscriptional evidences show that his kingdom was extended up to the present-day Comilla-Noakhali-Chittagong region. A later ruler of the dynasty Ariraja-Danuja-Madhava Dasharathadeva extended his kingdom to cover much of East Bengal.[19]

Late Middle Ages - Advent of Islam

Islam made its first appearance in the Bengal region during the 7th century AD by Arab Muslim traders and Sufi missionaries, and the subsequent Muslim conquest of Bengal in the 12th century lead to the rooting of Islam across the region.[20] Beginning in 1202, a military commander from the Delhi Sultanate, Bakhtiar Khilji, overran Bihar and Bengal. He conquered Nabadwip from the old emperor Lakshman Sen in 1203.[21] and intruded into much of Bengal as far east as Rangpur and Bogra ushering Muslim rule in this part of the world.[22] Under the Muslim rulers, Bengal entered a new era as cities were developed; palaces, forts, mosques, mausoleums and gardens sprang up; roads and bridges were constructed; and new trade routes brought prosperity and a new cultural life.[23]

However, smaller Hindu states continued to exist in the Southern and the Eastern parts of Bengal till the 1450s such as the Deva dynasty. Some independent small Hindu states were also established in Bengal during the Mughal period like those of Maharaja Pratapaditya of Jessore and Raja Sitaram Ray of Burdwan. These kingdoms contributed a lot to the economic and cultural landscape of Bengal. Militarily, these served as bulwarks against Portuguese and Burmese attacks. Many of these kingdoms are recorded to have fallen during the late 1700s. While Koch Bihar Kingdom in the North, flourished during the period of 16th and the 17th centuries as well till the advent of the British.

Turkic rule

In 1203 AD, the first Muslim ruler, Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turk, captured Nadia and established Muslim rule. The political influence of Islam began to spread in Bengal with the conquest of Nadia, the capital city of the Sen ruler Lakshmana, by him. Bakhtiyar captured Nadia in a unique way. Sensing the presence of a strong army of Lakshmana Sen on the main route to Nadia, Bakhtyar proceeded instead through the jungle of Jharkhand. He divided his army into several groups, and he himself led a group of horsemen and advanced towards Nadia in the guise of horse-traders. In this manner, Bakhtiyar had no problem in entering through the gates of the royal palace. Shortly afterwards, Bakhityar's main army also joined him and within a short while Nadia was captured. After capturing Nadia, Bakhtiyar advanced towards Gauda (Lakhnuti), another capital of the Sena kingdom, conquered it and made it his capital in 1205. Next year, Bakhtiyar set out for an expedition to capture Tibet, but this attempt failed and he had to return to Bengal with poor health and a reduced army. Shortly afterwards, he was killed by one of his commanders, Ali Mardan Khalji.[24] Defeated Lakshman Sen and his two sons moved to a place then called Vikramapur (present-day Munshiganj District in Bangladesh), where their diminished dominion lasted until the late 13th century.

Khiljis

The period after Bakhtiar Khilji's death in 1207 devolved into infighting among the Khiljis - representative of a pattern of succession struggles and intra-empire intrigues during later Turkic regimes. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz Khalji prevailed and extended the Sultan's domain south to Jessore and made the eastern Bang province a tributary. The capital was made at Lakhnauti on the Ganges near the older Bengal capital of Gaur. He managed to make Kamarupa and Trihut pay tribute to him. But he was later defeated by Shams-ud-Din Iltutmish.

Mamluk rule

The weak successors of Iltutmish encouraged the local governors to declare independence. Bengal was sufficiently remote from Delhi that its governors would declare independence on occasion, styling themselves as Sultans of Bengal. It was during this time that Bengal earned the name "Bulgakpur" (land of the rebels). Tughral Togun Khan added Oudh and Bihar to Bengal. Mughisuddin Yuzbak also conquered Bihar and Oudh from Delhi but was killed during an unsuccessful expedition in Assam. Two Turkic attempts to push east of the broad Jamuna and Brahmaputra rivers were repulsed, but a third led by Mughisuddin Tughral conquered the Sonargaon area south of Dhaka to Faridpur, bringing the Sen Kingdom officially to an end by 1277. Mughisuddin Tughral repulsed two massive attacks of the sultanate of Delhi before finally being defeated and killed by Ghiyas ud din Balban.

Mahmud Shahi dynasty

Mahmud Shahi dynasty started when Nasiruddin Bughra Khan declared independence in Bengal. Thus Bengal regained her independence back. Nasiruddin Bughra Khan and his successors ruled Bengal for 23 years finally being incorporated into Delhi Sultanate by Ghyiasuddin Tughlaq.

Ilyas Shahi dynasty

_002.jpg)

Shamsuddin Iliyas Shah founded an independent dynasty that lasted from 1342 to 1487. The dynasty successfully repulsed attempts by Delhi to conquer them. They continued to reel in the territory of modern-day Bengal, reaching to Khulna in the south and Sylhet in the east. The sultans advanced civic institutions and became more responsive and "native" in their outlook and cut loose from Delhi. Considerable architectural projects were completed including the massive Adina Mosque and the Darasbari Mosque which still stands in Bangladesh near the border. The Sultans of Bengal were patrons of Bengali literature and began a process in which Bengali culture and identity would flourish. During the rule of this dynasty, Bengal, for the first time, achieved its identity. Indeed, Ilyas Shah named this province as 'Bangalah' and united different parts into a single, unified territory.Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Ilyas Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. The Ilyas Shahi Dynasty was interrupted by an uprising by the Hindus under Raja Ganesha. However the Ilyas Shahi dynasty was restored by Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah. Famous globe-trotter, Ibn Battuta arrived Bengal this reign.Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2012). "Ibn Battuta". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. In his account of Bengal in his Rihla Rihla, he depicts a land full of abundance. Bengal was a progressive state with commercial links to China, Java, Ceylon. Merchant ships were available from various destinations.

Ganesha dynasty

.jpg)

The Ganesha dynasty began with Raja Ganesha in 1414. After Raja Ganesha seized control over Bengal he faced an imminent threat of invasion. Ganesha appealed to a powerful Muslim holy man named Qutb al Alam, to stop the threat. The saint agreed on the condition that Raja Ganesha's son Jadu would convert to Islam and rule in his place. Raja Ganesha agreed and Jadu started ruling Bengal as Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah in 1415 AD. Qutb al Alam died in 1416 AD and Raja Ganesha was emboldened to depose his son and accede to the throne himself as Danujamarddana Deva. Jalaluddin was reconverted to Hinduism by the Golden Cow ritual. After the death of his father he once again converted to Islam and started ruling his second phase.[25] Jalaluddin's son, Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah ruled for only 3 years due to chaos and anarchy. The dynasty is known for their liberal policy as well as justice and charity.

Hussain Shahi dynasty

The Habshi rule gave way to the Hussain Shahi dynasty that ruled from 1494 to 1538. Alauddin Hussain Shah, considered as the greatest of all the sultans of Bengal for bringing cultural renaissance during his reign. He extended the sultanate all the way to the port of Chittagong, which witnessed the arrival of the first Portuguese merchants. Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah gave refuge to the Afghan lords during the invasion of Babur though he remained neutral. However Nusrat Shah made a treaty with Babur and saved Bengal from a Mughal invasion. The last Sultan of the dynasty, who continued to rule from Gaur, had to contend with rising Afghan activity on his northwestern border. Eventually, the Afghans broke through and sacked the capital in 1538 where they remained for several decades until the arrival of the Mughals.

Pashtun rule

Suri dynasty

Sher Shah Suri established the Sur dynasty in Bengal. After the battle of Chausa he declared himself independent Sultan of Bengal and Bihar. Sher Shah was the only Muslim Sultan of Bengal to establish an empire in northern India. The Delhi Sultanate Islam Shah appointed Muhammad Khan Sur as the governor of Bengal. After the death of Islam Shah, Muhammad Khan Sur became independent. Muhammad Khan Sur was followed by Ghyiasuddin Bahadur Shah and Ghyiasuddin Jalal Shah. The Pashtun rule in Bengal remained for 44 years. Their most impressive achievement was Sher Shah's construction of the Grand Trunk Road connecting Sonargaon, Delhi and Kabul.

Karrani dynasty

The Sur dynasty was followed by the Karrani dynasty. Sulaiman Khan Karrani annexed Odisha to the Muslim sultanate permanently. Daoud Shah Karrani declared independence from Akbar which led to four years of bloody war between the Mughals and the Pashtuns. The Mughal onslaught against the Pashtun Sultan ended with the battle of Rajmahal in 1576, led by Khan Jahan. However, the Pashtun and the local landlords (Baro Bhuyans) led by Isa Khan resisted the Mughal invasion.

Sonargaon Sultanate

Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah ruled an independent kingdom in areas that lie within modern-day eastern and southeastern Bangladesh from 1338 to 1349 AD.[26] He was the first Muslim ruler to conquest Chittagong, the principal port of Bengal region in 1340 AD.[27] Fakhruddin's capital was Sonargaon[26] which emerged as the principal city of the region as the capital of an independent sultanate during his reign.[28] Ibn Batuta, the famous Moroccan explorer, after visiting his capital in 1346, described Shah as "a distinguished sovereign who loved strangers, particularly the fakirs and Sufis."[26][29]

Mughal period

Bengal came into the domain of Mughal Empire during the reign of Akbar after the Battle of Tukaroi which was fought in 1575 near the village of Tukaroi now in Balasore District, West Bengal between the Mughals and the Karrani Sultanate of Bengal and Bihar. [30] At that time Dhaka became the capital of the Mughal province of Bengal. But due to its geographical remoteness it was a bit difficult to govern the region. Especially the section east of the Brahmaputra river remained outside the mainstream Mughal influence. The Bengali ethnic and linguistic identity further crystallized during this period, since the whole of Bengal was united under an able and long-lasting administration. Furthermore, its inhabitants were given sufficient autonomy to cultivate their own customs and literature.

In 1612, during Emperor Jahangir's reign, the defeat of Sylhet completed the Mughal conquest of Bengal with the exception of Chittagong. At this time Dhaka rose in prominence by becoming the provincial capital of Bengal. Chittagong was later annexed in order to stifle Arakanese raids from the east. A well-known Dhaka landmark, Lalbagh Fort, was built during Aurangzeb's sovereignty.

Islam Khan

Islam Khan was appointed the Subahdar of Bengal in 1608 by Mughal emperor Jahangir. He ruled Bengal from his capital Dhaka which he renamed as Jahangir Nagar.[31] His major task was to subdue the rebellious Rajas, Bara-Bhuiyans, Zamindars and Afghan chiefs. He fought with Musa Khan, the leader of Bara-Bhuiyans and by the end of 1611 he was subdued.[31] Islam Khan also defeated Pratapaditya of Jessore, Ram Chandra of Bakla and Ananta Manikya of Bhulua.[31] Then he annexed the kingdoms of Koch Bihar, Koch Hajo and Kachhar thus taking total control over entire Bengal excepting Chittagong.[32]

Shaista Khan

Shaista Khan was appointed the Subahdar (Governor) of Bengal upon the death of Mir Jumla II in 1663.[33] He was the longest-serving governor of Bengal as he ably ruled the province from his administrative headquarters in Dhaka for almost 24 years from 1664 to 1688 AD.[33] As governor, he encouraged trade with Europe, Southeast Asia and other parts of India. He consolidated his power by signing trade agreements with European powers. Despite his powerful position he remained loyal to emperor Aurangzeb.[32]

Shaista Khan’s great fame in Bengal chiefly rests on his re-conquest of Chittagong. Though Chittagong came under the suzerainty of Bengal during Sultan Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah's reign in 1342 and the Bengal Sultanate until the 16th century,[32] it subsequently went to the hands of Arakanese rulers in 1530. Considering the strategic importance of the Chittagong port, Shaista Khan gave highest priority to recapture it and conquested Chittagong in January 1666 AD.[33] The conquest brought a relief and peace much to the popular mass as pirates have caused a great distress to public life.

The Nawabs of Bengal

Murshid Quli Khan ended the nominal Mughal rule in 1717 when he declared Bengal's independence from the Mughal empire. He shifted the capital to Murshidabad ushering in a series of independent Bengal Nawabs.

The founder of the Nasiri, Murshid Quli Jafar Khan, was born a poor Deccani Oriya Brahmin before being sold into slavery and bought by one Haji Shafi Isfahani, a Persian merchant from Isfahan who converted him to Islam. He entered the service of the Emperor Aurangzeb and rose through the ranks before becoming Nazim of Bengal in 1717, a post he held until his death in 1727. He in turn was succeeded by his grandson and son-in law until his grandson was killed in battle and succeeded by Alivardi Khan of the Afshar Dynasty in 1740.

The Afshar, ruled from 1740 to 1757. They were succeeded by the third and final dynasty to rule Bengal, the Najafi, when Siraj Ud Daula, the last of the Afshar rulers was killed at the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

Nawab Alivardi Khan showed military skill during his wars with the Marathas when they first invaded Bengal. He repulsed the first Maratha invasion from Bengal. He crushed an uprising of the Afghans in Bihar and made the British pay 150,000 Tk for blocking Mughal and Armenian trade ships. But the Marathas of the Maratha Empire invaded Bengal again and during the fourth Maratha invasion the Nawab Alivardi Khan was defeated and compelled to come to terms with the Marathas of the Maratha Empire.[34] He agreed to pay twelve lakhs of rupees annually as the chauth of Bengal, and ceded the province of Orissa to the Marathas.[34]

Colonial era

Europeans in Bengal

Portuguese traders and missionaries were the first Europeans to reach Bengal in the latter part of the 15th century. They established themselves in Chittagong and Hoogly. In 1632, the Mughal Subahdar of Bengal Kasim Khan Mashadi expelled the Portuguese in the Battle of Hoogly.

Dutch, French, and British East India Companies and representatives from Denmark soon followed contact with Bengal.

During Aurangzeb's reign, the local Nawab sold three villages, including one then known as Calcutta, to the British. Calcutta was Britain's first foothold in Bengal and remained a focal point of their economic activity. The British gradually extended their commercial contacts and administrative control beyond Calcutta to the rest of Bengal. Job Charnock was one of the first dreamers of a British empire in Bengal. He waged war against the Mughal authority of Bengal which led to the Anglo-Mughal war for Bengal (1686–1690). Shaista Khan, the Nawab of Bengal, defeated the British in the battles of Hoogly as well as Baleshwar and expelled the British from Bengal. Captain William Heath with a naval fleet moved towards Chittagong but it was a failure and he had to retreat to Madras.

British rule

The British East India Company gained official control of Bengal following the Battle of Plassey in 1757. This was the first conquest, in a series of engagements that ultimately lead to the expulsion of other European competitors. The defeat of the Mughals and the consolidation of the subcontinent under the rule of a corporation was a unique event in imperialistic history. Kolkata (Anglicized as "Calcutta") on the Hooghly became a major trading port for bamboo, tea, sugar cane, spices, cotton, muslin and jute produced in Dhaka, Rajshahi, Khulna, and Kushtia.

Scandals and the bloody rebellion known as the Sepoy Mutiny prompted the British government to intervene in the affairs of the East India Company. In 1858, authority in India was transferred from the Company to the crown, and the rebellion was brutally suppressed. Rule of India was organized under a Viceroy and continued a pattern of economic exploitation. Famine racked the subcontinent many times, including at least two major famines in Bengal. The British Raj was politically organized into seventeen provinces of which Bengal was one of the most significant.

Bengal Renaissance

|

|

The Bengal Renaissance refers to a social reform movement during the 19th and early 20th centuries in Bengal during the period of British rule. The Bengal renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833)[35] and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). Bengal in the 19th century was a unique blend of religious and social reformers, scholars, literary giants, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists, all merging to form the image of a renaissance, and marked the transition from the 'medieval' to the 'modern'.[36] Bangladeshi people are also very proud of their national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. He is greatly remembered for his active voice against the oppression of the British rulers in the 20th century. He was imprisoned for writing his most famous poem of "Bidrohee".

Partition of Bengal, 1905

The decision to effect the Partition of Bengal (Bengali: বঙ্গভঙ্গ) was announced in July 1905 by the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon. The partition took place on 16 October 1905 and separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western areas. The former province of Bengal was divided into two new provinces "Bengal" (comprising western Bengal as well as the province of Bihar and Orissa) and Eastern Bengal and Assam with Dacca as the capital of the latter.[37] Partition was promoted for administrative reasons: Bengal was geographically as large as France and had a significantly larger population. Curzon stated the eastern region was neglected and under-governed. By splitting the province, an improved administration could be established in the east, where subsequently, the population would benefit from new schools and employment opportunities. The Hindus of West Bengal who dominated Bengal's business and rural life complained that the division would make them a minority in a province that would incorporate the province of Bihar and Orissa.[38] Indians were outraged at what they recognised as a "divide and rule" policy,[39] where the colonisers turned the native population against itself in order to rule, even though Curzon stressed it would produce administrative efficiency. John barrier, had created the famously known invention, the barrier, In 1937. in an effort to both appease the Bengali sentiment and have easier administration. The partition was generally supported by the Muslims of East Bengal. Their support was motivated by both their poor economic conditions in East Bengal, as well as the perceived dominance of the Hindu businessmen and landlords in West Bengal over the governance of Bengal.

Due to political protests, the two parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. A new partition which divided the province on linguistic, rather than religious grounds followed, with the Hindi, Oriya and Assamese areas separated to form separate administrative units: Bihar and Orissa Province was created to the west, and Assam Province to the east. The administrative capital of British India was moved from Calcutta to New Delhi as well.

Movement for self-rule and Establishment of Pakistan

As the independence movement throughout British-controlled India began in the late 19th century gained momentum during the 20th century, Bengali politicians played an active role in Mohandas Gandhi's Congress Party and Mohammad Ali Jinnah's Muslim League, exposing the opposing forces of ethnic and religious nationalism. By exploiting the latter, the British probably intended to distract the independence movement, for example by partitioning Bengal in 1905 along religious lines. Partition of Bengal (1905) divided Bengal Presidency into an overwhelmingly Hindu west (including present-day Bihar and Odisha) and a predominantly Muslim east (including Assam).[40] Dhaka was made the capital of the new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam. But the split only lasted for seven years. The partition was abolished in 1911 due to severe opposition from Indian National Congress and a major section of the Bengali Hindus.[41]

Creation of Pakistan

The All-India Muslim League was founded on 30 December 1906, in the aftermath of partition of Bengal, on the sidelines of the annual All India Muhammadan Educational Conference in Shahbagh, Dhaka.[42] At first the Muslim League sought only to ensure minority Muslim rights in the future nation of independent India. However, in 1940 the Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution which envisaged one or more Muslim majority states in South Asia. The resolution unambiguously rejected the concept of a United India because of increasing inter-religious violence[43] The resolution was moved in the general session by Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Huq, the then Chief Minister of Bengal, and was adopted on 23 March 1940.[44] Non-negotiable was the inclusion of the Muslim parts of Punjab and Bengal in these proposed states. The stakes grew as a new Viceroy Lord Mountbatten of Burma was appointed expressly for the purpose of effecting a graceful British exit. Sectarian violence in Noakhali and Calcutta sparked a surge in support for the Muslim League, which won the majority seats in Bengal legislature in the 1946 election. This surge of support also emerged as a reaction against the British decision to reverse the 1905 Partition of Bengal, which the League regarded as a betrayal of the Bengali Muslims.[45] At the last moment Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Sarat Chandra Bose came up with the idea of an independent and unified Bengal state, which was endorsed by Jinnah. This idea was vetoed by the Indian National Congress.

British India was partitioned and the independent states of India and Pakistan were created in 1947; the region of Bengal was divided along religious lines. The predominantly Muslim eastern part of Bengal became the East Bengal (later renamed East Pakistan) province of Pakistan and the predominantly Hindu western part became the Indian state of West Bengal. Most of the Sylhet District of Assam also joined East Pakistan following a referendum .[46]

Pakistan's history from 1947 to 1971 was marked by political instability and economic difficulties. In 1956 a constitution was at last adopted, making the country an "Islamic republic within the Commonwealth". The nascent democratic institutions foundered in the face of military intervention in 1958, and the government imposed martial law between 1958 and 1962, and again between 1969 and 1971.

Almost from the advent of independent Pakistan in 1947, frictions developed between East and West Pakistan, which were separated by more than 1,000 miles of Indian territory. East Pakistanis felt exploited by the West Pakistan-dominated central government. Linguistic, cultural, and ethnic differences also contributed to the estrangement of East from West Pakistan.

The Bengali Language Movement

The Bengali Language Movement, also known as the Language Movement Bhasha Andolon, was a political effort in Bangladesh (then known as East Pakistan), advocating the recognition of the Bengali language as an official language of Pakistan. Such recognition would allow Bengali to be used in government affairs. Movement was led by Mufti Nadimul Quamar Ahmed. When the state of Pakistan was formed in 1947, its two regions, East Pakistan (also called East Bengal) and West Pakistan, were split along cultural, geographical, and linguistic lines. In 1948, the Government of Pakistan ordained Urdu as the sole national language, sparking extensive protests among the Bengali-speaking majority of East Pakistan. Facing rising sectarian tensions and mass discontent with the new law, the government outlawed public meetings and rallies. The students of the University of Dhaka and other political activists defied the law and organised a protest on 21 February 1952. The movement reached its climax when police killed student demonstrators on that day. The deaths provoked widespread civil unrest led by the Awami Muslim League, later renamed the Awami League. After years of conflict, the central government relented and granted official status to the Bengali language in 1956. On 17 November 1999, UNESCO declared 21 February International Mother Language Day for the whole world to celebrate,[47] in tribute to the Language Movement and the ethno-linguistic rights of people around the world.

Politics: 1954–1970

Great differences began developing between the two wings of Pakistan. While the west had a minority share of Pakistan's total population, it had the largest share of revenue allocation, industrial development, agricultural reforms and civil development projects. Pakistan's military and civil services were dominated by the Punjabis. Only one regiment in the Pakistani Army was Bengali. And many Bengali Pakistanis could not share the natural enthusiasm for the Kashmir issue, which they felt was leaving East Pakistan more vulnerable and threatened as a result. In 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the frontier leader of Awami League proclaimed a 6-point plan titled Our Charter of Survival at a national conference of opposition political parties at Lahore, in which he demanded self-government and considerable political, economic and defence autonomy for East Pakistan in a Pakistani federation with a weak central government. This led to the historic Six point movement.

Early 1968, Agartala Conspiracy Case was filed against Sheikh Mujib and 34 others, with the allegation that the accused were planning to liberate the East Pakistan; however, as the trial moved on, a mass uprising formed in protest against this accusation and in demand to free all the prisoners. Meanwhile, on February 15, 1969, one of the prisoners, Sergeant Zahurul Haq was shot dead at point blank range, which further enraged the public movement and eventually, the government had to withdraw the case on February 22. The mass uprising subsequently culminated into the historic Uprising of '69.

On March 25, 1969, General Ayub Khan handed the state power to General Yahya Khan; subsequently all sorts of political activities in the country were postponed by the new military President.

However, few of the students kept on their movement in a clandestine way; a new group called 'February 15 Bahini' was formed under the leadership of Serajul Alam Khan and Kazi Aref Ahmed, members of Swadhin Bangla Nucleus.

Later in 1969, Yahya Khan announced a fresh election date for October 5, 1970.

Independence movement

After the Awami League won all the East Pakistan seats as well as majority of the Pakistan's National Assembly in the 1970-71 elections, West Pakistan opened talks with the East on constitutional questions about the division of power between the central government and the provinces, as well as the formation of a national government headed by the Awami League.

The talks proved unsuccessful, however, and on March 1, 1971, Pakistani President Yahya Khan indefinitely postponed the pending National Assembly session, precipitating massive civil disobedience in East Pakistan.

On March 2, 1971, a group of students, led by A S M Abdur Rob, student leader & VP of DUCSU (Dhaka University Central Students Union) raised the new (proposed) flag of Bangladesh under the direction of Swadhin Bangla Nucleus. They demanded Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to declare the independence of Bangladesh immediately but Mujib refused to the strong demand. Rather he decided that he will declare his next steps on March 7 public meeting.

On March 3, 1971, student leader Shahjahan Siraj read the 'Sadhinotar Ishtehar' (Declaration of independence) at Paltan Maidan in front of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib along with student and public gathering under the direction of Swadhin Bangla Nucleus.

On March 7, there was a historical public gathering in Suhrawardy Udyan to hear updates on the ongoing movement from Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib, the frontier leader of movement that time. Although he avoided the direct speech of independence as the talks were still underway, he influenced the mob to prepare for any imminent war. The speech is considered a key moment in the war of liberation, and is remembered for the phrase,

- "Ebarer Shongram Amader Muktir Shongram, Ebarer Shongram Shadhinotar Shongram...."

- "Our struggle this time is a struggle for our freedom, our struggle this time is a struggle for our independence...."

Formal Declaration of Independence

After the military crackdown by the Pakistan army began during the early hours of March 26, 1971 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested and the political leaders dispersed, mostly fleeing to neighbouring India where they organized a provisional government afterwards. Before being held up by the Pakistani Army Sheikh Mujibur Rahman gave a hand note of the Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence and it was circulated amongst people and transmitted by the then East Pakistan Rifles' wireless transmitter. The world press reports from late March 1971 also make clear that Bangladesh’s declaration of independence by Bangabandhu was widely reported throughout the world. Bengali Army officer Major Ziaur Rahman captured Kalurghat Radio Station[48][49] in Chittagong and read the declaration of independence of Bangladesh on the evening hours of March 27, 1971.[50]

This is Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra. I, Major Ziaur Rahman, at the direction of Bangobondhu Mujibur Rahman, hereby declare that Independent People's Republic of Bangladesh has been established. At his direction, I have taken the command as the temporary Head of the Republic. In the name of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, I call upon all Bengalees to rise against the attack by the West Pakistani Army. We shall fight to the last to free our motherland. Victory is, by the Grace of Allah, ours. Joy Bangla.[51]

The Provisional Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh was formed on April 10 in Meherpur, (later renamed as Mujibnagar a place adjacent to the Indian border). Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was announced to be the head of the state. Tajuddin Ahmed became the prime minister of the government, Syed Nazrul Islam became the acting president and Khondaker Mostaq Ahmed the Foreign Minister. There the war plan was sketched with armed forces established named "Muktifoujo". Later it was named "Muktibahini" (freedom fighters). M. A. G. Osmani was assigned as the Chief of the force. The land sketched into 11 sectors under 11 sector commanders. Along with this sectors on the later part of the war Three special forces were formed namely Z Force, S Force and K Force. These three forces name were derived from the initial letter of the commandar's name. The training and most of the arms and ammunitions were arranged by the Meherpur government which were supported by India. As fighting grew between the Pakistan Army and the Bengali Mukti Bahini, an estimated ten million Bengalis, mainly Hindus, sought refuge in the Indian states of Assam, Tripura and West Bengal.

The crisis in East Pakistan produced new strains in Pakistan's troubled relations with India. The two nations had fought a war in 1965, mainly in the west, but the pressure of millions of refugees escaping into India in autumn of 1971 as well as Pakistani aggression reignited hostilities with Pakistan. Indian sympathies lay with East Pakistan, and on December 3, 1971, India intervened on the side of the Bangladeshis which led to a short, but violent, two-week war known as the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.

Pakistani capitulation and aftermath

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Army forces located in East Pakistan signed the Instrument of Surrender and the nation of Bangla Desh ("Country of Bengal") was finally established the following day. At the time of surrender only a few countries had provided diplomatic recognition to the new nation. Over 90,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian forces making it the largest surrender since World War II.[52][53] The new country changed its name to Bangladesh on January 11, 1972 and became a parliamentary democracy under a constitution. Shortly thereafter on March 19 Bangladesh signed a friendship treaty with India. Bangladesh sought admission in the UN with most voting in its favour, but China vetoed this as Pakistan was its key ally.[54] The United States, also a key ally of Pakistan, was one of the last nations to accord Bangladesh recognition.[55] To ensure a smooth transition, in 1972 the Simla Agreement was signed between India and Pakistan. The treaty ensured that Pakistan recognised the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani PoWs. India treated all the PoWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925.[56] It released more than 93,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months.[52]

Furthermore, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were also pardoned by India. The accord also gave back more than 13,000 km2 (5,019 sq mi) of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas;[57] most notably Kargil (which would in turn again be the focal point for a war between the two nations in 1999).

People's Republic of Bangladesh

Constitution

After Bangladesh achieved recognition from major countries, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman briefly assumed the provisional presidency. He charged the provisional parliament to write a new constitution. The constitution proclaims Bangladesh as a secular democratic republic,[58] declares the fundamental rights and freedoms of Bangladeshi citizens, spells out the fundamental principles of state policy, and establishes the structure and functions of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the republic. Passed by the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh on November 4, 1972, it came into effect from December 16, 1972, on the first anniversary of Bangladesh's victory over Pakistan in the Liberation War. The constitution proclaims nationalism, democracy, socialism and secularity as the national ideals of the Bangladeshi republic. When adopted in 1972, it was one of the most liberal constitutions of the time.[59][60][61]

Sheikh Mujib Administration (1971–1975)

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman came to office with immense personal popularity but had difficulty transforming this popular support into the political strength needed to function as head of government. The new constitution, which came into force on 16 December 1972, created a strong executive prime minister, a largely ceremonial presidency, an independent judiciary, and a unicameral legislature on a modified Westminster model.

The 1972 constitution adopted as state policy the Awami League's (AL) four basic principles of nationalism, secularism, socialism, and democracy.[62]

The first parliamentary elections held under the 1972 constitution were on 7 March 1973, with the Awami League winning a massive majority. No other political party in Bangladesh's early years was able to duplicate or challenge the League's broad-based appeal, membership, or organizational strength. Relying heavily on experienced civil servants and members of the Awami League, the new Bangladesh government focused on relief, rehabilitation, and reconstruction of the economy and society. Economic conditions remained precarious, however.

In 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman introduced the Collaborators Act 1972 with a view to trying war criminals which was followed by a general amnesty in 1973 amid some conditions like no criminals with specific charges of arson, murder and rape will remain under the purview of the act.

In December 1974, Mujib decided that continuing economic deterioration and mounting civil disorder required strong measures. After proclaiming a state of emergency, Mujib used his parliamentary majority to win a constitutional amendment limiting the powers of the legislative and judicial branches, establishing an executive presidency, and instituting a one-party system, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), which all members of Parliament (and senior civil and military officials) were obliged to join.[62] To eshtablish one-party system all the political parties, including Awami League, were banned.

Despite some improvement in the economic situation during the first half of 1975, implementation of promised political reforms was slow, and criticism of government policies became increasingly centered on Mujib. On 15 August 1975, Mujib, and most of his family, were assassinated by mid-level army officers. His daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, were out of the country. A new government, headed by former Mujib associate Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad, was formed.[62]

Ziaur Rahman Zia (1977-1981)

Two Army uprisings on 3 November and 7 November 1975 led to a reorganised structure of power in Bangladesh. A state of emergency was declared to restore order and calm. Mushtaq resigned, and the country was placed under temporary martial law, with three service chiefs serving as deputies to the new president, Justice Abu Sayem, who also became the Chief Martial Law Administrator. Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman took over the presidency in 1977 when Justice Sayem resigned. President Zia reinstated multi-party politics, introduced free markets, and founded the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). At that situation of multi-party politics, former Awami League was reorganized. Zia's rule ended when he was assassinated by elements of the military in 1981.

Ershad Era (1982-1990)

Bangladesh's next major ruler was Lieutenant General Hossain Mohammad Ershad, who gained power in a coup on 24 March 1982, and ruled until 6 December 1990, when he was forced to resign after a revolt of all major political parties and the public, along with pressure from Western donors (which was a major shift in international policy after the fall of the Soviet Union).

Democratic era (1991–present)

A constitutional referendum was held in Bangladesh on 15 September 1991. Voters were asked "Should or not the President assent to the Constitution (Twelfth Amendment) Bill, 1991 of the People's Republic of Bangladesh?" The amendments would lead to the reintroduction of parliamentary government, with the President becoming the constitutional head of state, but the Prime Minister the executive head. It also abolished the position of Vice-President and would see the President elected by Parliament. Since then, Bangladesh has reverted to a parliamentary democracy. Zia's widow, Khaleda Zia, led the Bangladesh Nationalist Party to parliamentary victory at the general election in 1991 and became the first female Prime Minister in Bangladeshi history. However, the Awami League, headed by Sheikh Hasina, one of Mujib's surviving daughters, won the next election in 1996. The Awami League lost again to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party in 2001.

Widespread political unrest followed the resignation of the BNP in late October 2006, but the caretaker government worked to bring the parties to election within the required ninety days. At the last minute in early January, the Awami League withdrew from the election scheduled for later that month. On 11 January 2007, the military intervened to support both a state of emergency and a continuing but neutral caretaker government under a newly appointed Chief Advisor, who was not a politician. The country had suffered for decades from extensive corruption,[63] disorder, and political violence. The caretaker government worked to root out corruption from all levels of government. It arrested on corruption charges more than 160 people, including politicians, civil servants, and businessmen, among whom were both major party leaders, some of their senior staff, and two sons of Khaleda Zia.

After working to clean up the system, the caretaker government held what was described by observers as a largely free and fair election on 29 December 2008.[64] The Awami League's Sheikh Hasina won with a two-thirds landslide in the elections; she took the oath of Prime Minister on 6 January 2009.[65]

See also

- East Bengal

- East Pakistan

- History of Asia

- History of Assam

- History of Bengal

- History of Bangladesh after independence

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- History of South Asia

- List of Presidents of Bangladesh

- List of Prime Ministers of Bangladesh

- List of rulers of Bengal

- Politics of Bangladesh

- Timeline of Bangladeshi history

- Timeline of Dhaka

References

- ↑ Frank Jacobs (January 6, 2013). "Peacocks at Sunset". Opinionator: Borderlines. The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal, Ghulam Husain Salim, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902.

- ↑ Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450-1200 A.D. by Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha p.181

- ↑ India: A History by John Keay p.220

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.145

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.281

- 1 2 Bangladesh (People'S Republic Of Bangladesh) Pax Gaea World Post Human Rights Report. Paxgaea.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Shaffer, Jim. 1993, "Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond." In Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times, ed. H. Spodek and D.M. Srinivasan.

- ↑ http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/CulturesSocietiesIndusTrad.pdf

- ↑ Millard Fuller. "(अंगिका) Language : The Voice of Anga Desh". Angika. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi: Pearson Education. pp. 260–4. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ↑ Nitish K. Sengupta (1 January 2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- ↑ Biplab Dasgupta (1 January 2005). European Trade and Colonial Conquest. Anthem Press. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-1-84331-029-7.

- 1 2 Sailendra Nath Sen (1 January 1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–287. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ↑ George E. Somers (1 January 1977). Dynastic History Of Magadha. Abhinav Publications. p. 185. ISBN 978-81-7017-059-4.

- 1 2 3 Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib by Nitish K. Sengupta p.45

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.10

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of North-East India by T. Raatan p.143

- ↑ Roy, Niharranjan (1993). Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba Calcutta: Dey's Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, pp.408-9

- ↑ Eaton, R (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20507-3. OCLC 26634922 76881262.

- ↑ "District Website of Nadia". Government of West Bengal.Retrieved: 2014-02-12

- ↑ Sen, Amulyachandra (1954). Rajagriha and Nalanda. Institute of Indology, volume 4. Calcutta: Calcutta Institute of Indology, Indian Publicity Society. p. 52. OCLC 28533779.

- ↑ "History of Bangladesh". Lonely Planet.Retrieved: 2014-02-16

- ↑ "International Education Programmes and Qualifications from Cambridge". projects.cie.org.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ↑ Biographical encyclopedia of Sufis By N. Hanif, pg.320

- 1 2 3 Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2012). "Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ "About Chittagong:History". Local Government Engineering Department, Government of Bangladesh.Retrieved: 2014-03-09

- ↑ Historical Sites needs to be preserved, The Daily Star, September 5, 2009,Retrieved: 2014-03-09

- ↑ Ibn Batuta, Famous Bengalis and Related Topics, Retrieved: 2014-03-09

- ↑ The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods By Mountstuart Elphinstone, Edward Byles Cowell, Published by J. Murray, Calcutta 1889, Public Domain

- 1 2 3 Karim, Abdul (2012). "Islam Khan Chisti". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 3 Sarkar, Jadunath (2003). The History of Bengal (Volume II): Muslim Period. Delhi: B.R. Publishing. ISBN 81-7646-239-X.

- 1 2 3 Karim, Abdul (2012). "Shaista Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- 1 2 Sirajuddaullah and the East India Company, 1756-1757: by Brijen Kishore Gupta p.23

- ↑ History of the Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta, p 211, UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- ↑ Sumit Sarkar, "Calcutta and the Bengal Renaissance", in Calcutta, the Living City ed. Sukanta Chaudhuri, Vol I, p. 95.

- ↑ David Gilmour, Curzon: Imperial Statesman (1994) pp 271–3

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, "the creation of the barrier" http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/60754/partition-of-Bengal

- ↑ Bipan Chandre Lal, "History of Modern India", ISBN 978-81-250-3684-5, pp 248–249

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Partition of Bengal" http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/60754/partition-of-Bengal

- ↑ Gordon Johnson, "Partition, Agitation and Congress: Bengal 1904 To 1908," Modern Asian Studies, (May 1973) pp 533–588

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1985). The sole spokesman : Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the demand for Pakistan. Cambridge (UK); New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24462-6.

- ↑ Malik, Muhammad Aslam (2001). The making of the Pakistan resolution. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579538-7.

- ↑ Qutubuddin Aziz. "Muslim's struggle for independent statehood". Jang Group of Newspapers. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (1986). A History of India. Totowa, New Jersey: Barnes & Noble. pp. 300–312. ISBN 978-0-389-20670-5.

- ↑ "Sylhet (Assam) to join East Pakistan". Keesing's Record of World Events. July 1947. p. 8722.

- ↑ Glassie, Henry and Mahmud, Feroz.2008.Living Traditions. Cultural Survey of Bangladesh Series-II. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Dhaka. p.578

- ↑ Admin. (2011-03-20). "Major Ziaur Rahman's revolt with 8 East Bengal Regiment at Chittagong". Newsbd71.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ↑ Ziaur Rahman's interview

- ↑ BDNEWS24.com

- ↑ JYOTI SEN GUPTA, NAYA PROKASH, 206, BIDHAN SARANI, CALCUTTA-6, FIRST EDITION, 1974, CHAPTER-15, PAGE-325 and 326. HISTORY OF FREEDOM MOVEMENT IN BANGLADESH, 1943-1973: SOME INVOLVEMENT.

- 1 2 "54 Indian PoWs of 1971 war still in Pakistan". DailyTimes. January 19, 2005. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ↑ "The 1971 war". BBC News. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ↑ Section 9. Situation in the Indian Subcontinent, 2. Bangladesh's international position – Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- ↑ who's coming to dinner Naeem Bangali

- ↑ "Bangladesh: Unfinished Justice for the crimes of 1971 – South Asia Citizens Web". Sacw.net. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Simla Agreement 1972 – Story of Pakistan". Storyofpakistan.com. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ↑ "HC rules Bangladesh secular | Bangladesh". bdnews24.com. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- ↑ "Govt happy". Thedailystar.net. 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- ↑ "Constitution to get back on '72 track". Thedailystar.net. 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- ↑ "Index of /pmolib/constitution". Pmo.gov.bd. 2009-06-14. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- 1 2 3 "Background Note: Bangladesh". Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs (March 2008). Accessed June 11, 2008. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Rahman, Waliur (18 October 2005). "Bangladesh tops most corrupt list". BBC News. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ "Bangladesh election seen as fair, though loser disputes result". The New York Times. 30 November 2008.

- ↑ "Hasina takes oath as new Bangladesh prime minister". Reuters. 6 January 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

Sources

- CIA World Factbook (July 2005). Bangladesh

- US Department of State (August 2005). "Background Note: Bangladesh"

- Ahmed, Helal Uddin (2012). "History". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Library of Congress (1988). A Country Study: Bangladesh

- BONAZZI, Eros, Storia del Bengala e del Bangladesh, Azeta Fastpress, 2011. ISBN 978-88-89982-30-3

- "Declaration of Independence of Bangladesh Original Speech by Ziaur Rahman". scribd.com. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

Further reading

- Raghavan, Srinath. 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh (Harvard University Press; 2014) 258 pages; scholarly history with worldwide perspective

External links

- Rulers.org — Bangladesh List of rulers for Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Newspapers & Magazine Directory

- Bangla Newspapers & Magazine Directory

- Bangla Newspapers & Magazine Directory

| ||||||||||||||