Returns to scale

In economics, returns to scale and economies of scale are related but different terms that describe what happens as the scale of production increases in the long run, when all input levels including physical capital usage are variable (chosen by the firm). The term returns to scale arises in the context of a firm's production function. It explains the behavior of the rate of increase in output (production) relative to the associated increase in the inputs (the factors of production) in the long run. In the long run all factors of production are variable and subject to change due to a given increase in size (scale). While economies of scale show the effect of an increased output level on unit costs, returns to scale focus only on the relation between input and output quantities.

The laws of returns to scale are a set of three interrelated and sequential laws: Law of Increasing Returns to Scale, Law of Constant Returns to Scale, and Law of Diminishing returns to Scale. If output increases by that same proportional change as all inputs change then there are constant returns to scale (CRS). If output increases by less than that proportional change in inputs, there are decreasing returns to scale (DRS). If output increases by more than that proportional change in inputs, there are increasing returns to scale (IRS). A firm's production function could exhibit different types of returns to scale in different ranges of output. Typically, there could be increasing returns at relatively low output levels, decreasing returns at relatively high output levels, and constant returns at one output level between those ranges.

In mainstream microeconomics, the returns to scale faced by a firm are purely technologically imposed and are not influenced by economic decisions or by market conditions (i.e., conclusions about returns to scale are derived from the specific mathematical structure of the production function in isolation).

Example

When all inputs increase by a factor of 2, new values for output will be:

- Twice the previous output if there are constant returns to scale (CRS)

- Less than twice the previous output if there are decreasing returns to scale (DRS)

- More than twice the previous output if there are increasing returns to scale (IRS)

Assuming that the factor costs are constant (that is, that the firm is a perfect competitor in all input markets), a firm experiencing constant returns will have constant long-run average costs, a firm experiencing decreasing returns will have increasing long-run average costs, and a firm experiencing increasing returns will have decreasing long-run average costs.[1][2][3] However, this relationship breaks down if the firm does not face perfectly competitive factor markets (i.e., in this context, the price one pays for a good does depend on the amount purchased). For example, if there are increasing returns to scale in some range of output levels, but the firm is so big in one or more input markets that increasing its purchases of an input drives up the input's per-unit cost, then the firm could have diseconomies of scale in that range of output levels. Conversely, if the firm is able to get bulk discounts of an input, then it could have economies of scale in some range of output levels even if it has decreasing returns in production in that output range.

Formal definitions

Formally, a production function  is defined to have:

is defined to have:

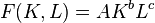

- Constant returns to scale if (for any constant a greater than 0)

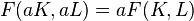

- Increasing returns to scale if (for any constant a greater than 1)

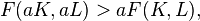

- Decreasing returns to scale if (for any constant a greater than 1)

where K and L are factors of production—capital and labor, respectively.

In a more general set-up, for a multi-input-multi-output production processes, one may assume technology can be represented via some technology set, call it  , which must satisfy some regularity conditions of production theory.[4][5][6][7][8] In this case, the property of constant returns to scale is equivalent to saying that technology set

, which must satisfy some regularity conditions of production theory.[4][5][6][7][8] In this case, the property of constant returns to scale is equivalent to saying that technology set  is a cone, i.e., satisfies the property

is a cone, i.e., satisfies the property  . In turn, if there is a production function that will describe the technology set

. In turn, if there is a production function that will describe the technology set  it will have to be homogeneous of degree 1.

it will have to be homogeneous of degree 1.

Formal example

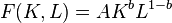

The Cobb-Douglas functional form has constant returns to scale when the sum of the exponents adds up to one. The function is:

where  and

and  . Thus

. Thus

But if the Cobb-Douglas production function has its general form

with  then there are increasing returns if b + c > 1 but decreasing returns if b + c < 1, since

then there are increasing returns if b + c > 1 but decreasing returns if b + c < 1, since

which is greater than or less than  as b+c is greater or less than one.

as b+c is greater or less than one.

See also

- Diseconomies of scale

- Economies of agglomeration

- Economies of scope

- Experience curve effects

- Ideal firm size

- Homogeneous function

- Mohring effect

- Moore's law

References

- ↑ Gelles, Gregory M.; Mitchell, Douglas W. (1996). "Returns to scale and economies of scale: Further observations". Journal of Economic Education 27 (3): 259–261. JSTOR 1183297.

- ↑ Frisch, R. (1965). Theory of Production. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

- ↑ Ferguson, C. E. (1969). The Neoclassical Theory of Production and Distribution. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07453-3.

- ↑ • Shephard, R.W. (1953) Cost and production functions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ • Shephard, R.W. (1970) Theory of cost and production functions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ • Färe, R., and D. Primont (1995) Multi-Output Production and Duality: Theory and Applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston.

- ↑ • Zelenyuk, V. (2013) “A scale elasticity measure for directional distance function and its dual: Theory and DEA estimation.” European Journal of Operational Research 228:3, pp 592–600

- ↑ • Zelenyuk V. (2014) “Scale efficiency and homotheticity: equivalence of primal and dual measures” Journal of Productivity Analysis 42:1, pp 15-24.

Further reading

- Susanto Basu (2008). "Returns to scale measurement," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

- James M. Buchanan and Yong J. Yoon, ed. (1994) The Return to Increasing Returns. U.Mich. Press. Chapter-preview links.

- John Eatwell (1987). "Returns to scale," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 165–66.

- Färe, R., S. Grosskopf and C.A.K. Lovell (1986), “Scale economies and duality” Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 46:2, pp. 175–182.

- Hanoch, G. (1975) “The elasticity of scale and the shape of average costs,” American Economic Review 65, pp. 492–497.

- Panzar, J.C. and R.D. Willig (1977) “Economies of scale in multi-output production, Quarterly Journal of Economics 91, 481-493.

- Joaquim Silvestre (1987). "Economies and diseconomies of scale," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 80–84.

- Spirros Vassilakis (1987). "Increasing returns to scale," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 761–64.

- Zelenyuk, V. (2013) “A scale elasticity measure for directional distance function and its dual: Theory and DEA estimation.” European Journal of Operational Research 228:3, pp 592–600

- Zelenyuk V. (2014) “Scale efficiency and homotheticity: equivalence of primal and dual measures” Journal of Productivity Analysis 42:1, pp 15-24.

External links

| ||||||||||