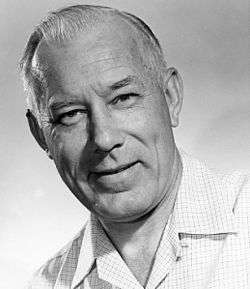

Ike Altgens

| Ike Altgens | |

|---|---|

|

Ike Altgens circa 1970 | |

| Born |

James William Altgens April 28, 1919[1] Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

December 12, 1995 (aged 76) Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1938–1979[2] |

| Employer | Associated Press |

| Known for | photographer/reporter/witness of assassination of John F. Kennedy |

| Spouse(s) | Clara B. Halliburton (m. 1944–1995) |

James William "Ike" Altgens[1] (/ˈɑːlt.ɡənz/;[3] April 28, 1919 – December 12, 1995) was an American photojournalist and field reporter for the Associated Press (AP) based in Dallas, Texas. Altgens began his career with the AP as a teenager and, following a stint with the United States Coast Guard, worked his way into a senior position with the AP Dallas bureau. While on assignment for the AP on November 22, 1963, Altgens made two historic photographs[4] during the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, including the image of Jacqueline Kennedy and Secret Service agent Clint Hill on the presidential limousine that would be reproduced on the front pages of newspapers around the world.[5] Seconds earlier, Altgens had made the soon-to-be controversial[6][7] photograph that led people in the United States and elsewhere to question whether accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was visible in the doorway of the Texas School Book Depository as the gunshots were fired.[8]

Altgens worked briefly as a film actor and model during his 40-year career with the AP, then did advertising work until he retired altogether. Both Altgens and his wife were in their seventies when they died in 1995, at about the same time, in their Dallas home.

Early life and career

Dallas native Ike Altgens was orphaned as a child and raised by a widowed aunt. In 1938, shortly after graduating from North Dallas High School, he was hired by the Associated Press. Altgens began his career at age 19 by doing odd jobs and writing the occasional sports story; by 1940, he had demonstrated an aptitude for photography and was assigned to work in the wirephoto office.[1]

His career was interrupted when he served in the United States Coast Guard during World War II, though he was able to moonlight as a radio broadcaster. Following his return to Dallas, he married Clara B. Halliburton in July 1944, and went back to work with the AP the following year. He also attended night classes at Southern Methodist University, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in speech with a minor in journalism.[1]

By 1959, Altgens had found additional work as an actor and model in motion pictures, television and print advertising.[9] Credited as James Altgens, he portrayed "Secretary Lloyd Patterson"[10] in the low-budget science fiction thriller Beyond the Time Barrier (1960); his role included the film's final line of dialogue: "Gentlemen, we have got a lot to think about."[11] Altgens' brief acting career also included a role as a witness in Free, White and 21 (1963),[12] and as a witness (though not portraying himself) in The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald (1964).[13]

Altgens photographed President Kennedy for the AP in 1961 at Perrin Air Force Base. Kennedy and former President Dwight D. Eisenhower were traveling to Bonham, Texas, in November to attend the funeral of Sam Rayburn, three-time Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. Earlier that day, Altgens was the only photojournalist to climb up to the 29th floor of the Mercantile National Bank Building to report on the rescue of a young girl from a burning elevator.[14]

Assassination of President Kennedy

Photojournalist

On November 22, 1963, Altgens was assigned to work in the Associated Press offices in Dallas as the photo editor. He asked instead to go to the railroad overcrossing where Elm, Main and Commerce Streets converge to photograph the motorcade that would take President Kennedy from Love Field to the Dallas Trade Mart, where Kennedy was to deliver an address. Since that was not originally his assignment, Altgens took his personal camera, a 35mm Nikkorex-F single lens reflex camera with a 105mm telephoto lens, rather than the motor-driven camera usually used for news events.[lower-alpha 1] "This meant that what I took, I had to make sure it was good—I didn't have time for second chances."[15]

Altgens tried to find a good camera angle on the overcrossing, but was turned away by uniformed officers who said it was private property; he moved to a location within Dealey Plaza instead.[16] He made photographs of the motorcade on Main Street as it approached Houston Street, then got a close-up as the presidential limousine turned right onto Houston.[17][lower-alpha 2] Afterwards, he ran across the grass toward the south curb along Elm Street, and stopped across from the Plaza's north colonnade. As he snapped his first photograph from that spot, simultaneous to Zapruder film frame 255,[19] he heard a "burst of noise", but did not recall having any reaction at that point since he thought the sound came from a firecracker.[17]

Witness to history

Moments later, as Altgens prepared for a second photograph along Elm Street, he heard a blast that he recognized as gunfire and saw the President had been struck in the head. Altgens would later write that his camera was focused and ready, "but when JFK's head exploded, sending substance in my direction, I virtually became paralyzed" and failed to press the trigger. "To have a President shot to death right in front of you and keep your cool and do what you're supposed to do—I'm not real sure that the most seasoned photographers would be able to do it. ... [But] there is no excuse for this. I should have made the picture that I was set up to make. And I didn't do it."[20]

Altgens' next photograph showed the First Lady with her hand on the vehicle's trunk lid and Secret Service agent Clint Hill standing on the bumper behind her as the driver had begun to accelerate.[21][lower-alpha 3] Mrs. Kennedy testified the following June that "there were pictures later on of me climbing out the back. But I don't remember that at all."[24] It was this photograph, splashed on the front pages of newspapers around the world, that would lead Hill to write in his 2013 book that he "would forever be known as the Secret Service agent who jumped on the back of the car."[25]

After the gunshots ended, Altgens saw what he would later describe as "Secret Service men, uniformed policemen with drawn guns racing up this little incline" between Elm Street and the railroad tracks, and he crossed the street into the "utter confusion" to see if he could get a picture of someone in custody.[26] When they came back without a suspect, Altgens hurried back to the AP offices in the Dallas Morning News building on Houston Street to file his report and have the film developed. His first phone call, from the AP wirephoto office to the news office,[27] led to one of the first bulletins sent to the world:

- DALLAS, NOV. 22 (AP)–PRESIDENT KENNEDY WAS SHOT TODAY JUST AS HIS MOTORCADE LEFT DOWNTOWN DALLAS. MRS. KENNEDY JUMPED UP AND GRABBED MR. KENNEDY. SHE CRIED, "OH, NO!" THE MOTORCADE SPED ON.[28]

Once his pictures had been distributed via the wirephoto network, Altgens was sent to Parkland Memorial Hospital along with a second photographer. Both stayed at Parkland until Kennedy's body was taken by hearse to Air Force One at Love Field.[5]

Altgens returned to Dealey Plaza to make photographs for diagramming the assassination site, then was sent to Dallas City Hall to retrieve some photos made by another AP photographer of Oswald in custody. This was "the first and only time" he would see the suspect, and Altgens thought Oswald looked like "they had put him through the interrogation wringer."[5]

The man resembling Lee Harvey Oswald

Ten days after Kennedy was assassinated, the Associated Press in Dallas reported that Altgens' first photograph along Elm Street had captured the attention of people "here and abroad" who noticed that one of the men standing in the main doorway to the book depository looked like Lee Harvey Oswald. If true, "it would seem to prove that he was not the Kennedy assassin" because he would not have had time to get there from the sixth floor. The AP report quoted depository superintendent Roy Truly, who identified another employee, Billy Lovelady, as the man in the image. The report also noted that the FBI had already investigated the photograph and had also identified Lovelady.[8]

On May 24, 1964, six months after the shooting, the New York Herald Tribune reported that Altgens—the man responsible for "probably the most controversial photograph of the decade" and one of a handful of people standing near the motorcade when Kennedy was shot—had not been questioned either by the FBI or by the Warren Commission.[6] The next day, a column appearing in Chicago's American made the same observation. FBI investigators interviewed Altgens eight days later, on June 2, 1964.[30][lower-alpha 4] By the time his testimony for the Warren Commission was taken on July 22,[32] Altgens was aware of the individual who resembled Oswald; Lovelady had been interviewed for the Herald Tribune article,[lower-alpha 5] and Altgens testified that he too had been contacted but, because he had had no assignments involving any depository employees either before or since the assassination, "naturally I had no information" to share.[29]

Several depository employees were interviewed for the Commission in an effort to determine the identity of the man in the depository doorway; hearings included testimony from five people who said Lovelady was either sitting or standing on the entrance steps, and from three others (including Lovelady) who identified him in Altgens' photograph.[lower-alpha 6] His supervisor signed an affidavit stating that Lovelady was sitting on the steps as the motorcade passed by.[42] Ultimately, the Commission decided that Oswald was not in the doorway.[43][lower-alpha 7]

In 1978, the House Select Committee on Assassinations studied several still and motion images, including an enhanced version of the Altgens photograph, in the scope of its investigation. The Committee also concluded that Lovelady was the man pictured in the depository doorway.[46]

Fifty years after the photo was first published, the official conclusions were still being argued by academics[47][48] and conspiracy theorists.[49] Texas journalist Jim Marrs, who had previously noted that most researchers were "ready to concede that the man may have been Lovelady", wrote in 2013 that there was a "growing resistance to this admission."[50]

Recollections of a witness

Two AP dispatches featuring Altgens were issued on November 22, 1963. He initially reported hearing two shots, but thought someone had been "shooting fireworks".[51] Altgens himself wrote, "At first I thought the shots came from the opposite side of the street. ... I did not know until later where the shots came from. I was on the opposite side of the President's car from the gunman. He might have hit me."[52] Altgens said he was told by the AP's Los Angeles photo editor that, had the shot gone "just a bit to the left ... you would have been the victim."[31]

In 1964, testifying for the Warren Commission, Altgens was asked about the gunfire and whether he knew its source. He answered that he had not been keeping track of the number of gunshots fired in Dealey Plaza. "I mean, who counts fireworks explosions? ... I could vouch for number one, and I can vouch for the last shot, but I cannot tell you how many shots were in between." Kennedy's wounds suggested to Altgens that the final shot "came from the opposite side, meaning in the direction of this depository building, but at no time did I know for certain where the shot came from."[53]

When CBS television interviewed him in 1967, Altgens said it was obvious to him that the head shot came from behind Kennedy's limousine "because it caused him to bolt forward, dislodging him from this depression in the seat cushion".[lower-alpha 8] He added that the commotion across the street after the shooting "seemed rather strange ... because knowing that the shot came from behind, this fellow had to really move in order to get over into the knoll area."[55]

Trial of Clay Shaw

District Attorney Jim Garrison subpoenaed Altgens to appear in New Orleans, Louisiana, for the 1969 trial of businessman Clay Shaw on charges of conspiring to kill Kennedy. A check for US$300 was sent to cover the airfare, but Altgens did not want to go; he thought Garrison's actions were "self-aggrandizement."[56]

Altgens "happened to run into" former Texas Governor John Connally in Houston a short time later.[lower-alpha 9] Connally told Altgens that he too had been called to testify and sent money for airfare, but he decided to cash the check and spend the money. Connally suggested that Altgens do the same.[56] Altgens later learned that neither he nor Connally would be called after all.[57]

Later life

Pictures of the Pain

Starting in 1984,[58] Altgens shared personal details and reminiscences in letters and telephone conversations for the book Pictures of the Pain: Photography and the Assassination of President Kennedy (1994).[lower-alpha 10] Altgens had retired from the AP in 1979 after more than 40 years, rather than accept a transfer to a different bureau. He spent his later years working on display advertising for the Ford Motor Company and answering repeated requests for interviews made by assassination researchers who failed to convince him that the Warren Commission's conclusion—that Oswald, acting alone, killed Kennedy—was wrong.[lower-alpha 11] At the same time, he conceded that "there will always be some controversy about details surrounding the site and shooting of the president."[59]

"Reporters Remember 11-22-63"

In November 1993, Altgens took part in "Reporters Remember 11-22-63" at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Broadcast on C-SPAN as Journalists Remember the JFK Assassination, the panel discussion featured members of the press who spoke of their experiences on the day 30 years earlier that JFK was killed. As he introduced Altgens, moderator Hugh Aynesworth recalled the picture that "became very controversial" because of the man "that looked like Oswald".[7]

Among his reminiscences, Altgens recalled having seen "no blood on the right-hand side of [Kennedy's] face; there was no blood on the front of his face. But there was a tremendous amount of blood on the left-hand side and at the back of the head." That suggested to him, he continued, that if there was gunfire from any direction other than the rear, "there would be evidence in that particular area".[60] He also remembered, when seeing Jackie Kennedy on the trunk of the limousine, thinking that she "was scared out of her mind and she was looking for a way to escape."[61]

No More Silence

Altgens was one of 49 eyewitnesses interviewed for the 1998 book No More Silence: An Oral History of the Assassination of President Kennedy. He recalled having been contacted by Billy Lovelady, who wanted a copy of Altgens' first photograph along Elm Street. When Altgens tried to deliver the materials, Lovelady's wife told him her husband would never agree to be interviewed. The couple had moved several times, but still suffered break-ins by people who wanted the shirt Lovelady wore when Kennedy was shot.[62][lower-alpha 12]

Altgens also recalled telling FBI agents that, had he been left alone on the overpass, he might have had better pictures for investigators. "By being up there, I would have been able to show the sniper."[64]

Death

On December 12, 1995, Ike and Clara Altgens were found dead in separate rooms in their home in Dallas. A Houston Chronicle article quoted a nephew, Dallas attorney Ron Grant, as saying his Aunt Clara "had been very ill for some time with heart trouble and many other problems. Both of them had had the flu for some time."[65] In addition, the Dallas Morning News said police were looking into the possibility that carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty furnace played a role in their deaths.[66] Altgens was survived by three nephews; his wife by two sisters.[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Pictures of the Pain, author Richard B. Trask wrote that Altgens' personal camera was a 35mm Nikkorex-F single lens reflex model, serial #371734, that he had purchased via the AP in January 1963 from Medo Photo Supply Corp. It originally included a 50mm lens, but on November 22 "the camera body was mounted with a 105mm telephoto lens and loaded with Eastman Kodak Tri-X pan film."[15]

- ↑ Altgens made seven photographs of the motorcade. Trask wrote that, by 1994, Altgens was not sure of the total and was "very adamant about not wanting to take credit for someone else's work." However, the negatives had been examined at the AP New York bureau by Richard E. Sprague, who found that Altgens' film "is of the same type (Tri-X), is numbered sequentially, is chronological, and taken from the same vantage points at which Altgens is known to have been located."[18]

- ↑ Under questioning for the Warren Commission, Hill—who was assigned to Mrs. Kennedy—testified that she "was, it appeared to me, reaching for something coming off the right rear bumper of the car". Asked if there was "anything back there that [you] observed, that [Mrs. Kennedy] might have been reaching for", Hill said that he "thought I saw something come off the back, too, but I cannot say that there was."[22] For his book Five Days in November, Hill recalled thinking, "Oh God. She's reaching for some material that's come out of the president's head."[23]

- ↑ Altgens told author Larry A. Sneed that he had asked his bureau chief whether he should contact the FBI. He was told, "If they want information, we're available, but we don't go volunteering."[31]

- ↑ In this article, reprinted as part of Warren Commission Exhibit No. 1408,[33] Lovelady recalled a visit from two FBI agents the night after the assassination. When he identified himself in Altgens' photo, Lovelady said one agent "had a big smile on his face because it wasn't Oswald. They said they had a big discussion down at the FBI and one guy said it just had to be Oswald."

- ↑ Those who saw Lovelady: Buell Wesley Frazier,[34] James Jarman,[35] Harold Norman,[36] Sarah Stanton[37] and William Shelley.[38] Those who identified him in Altgens #6: Danny Garcia Arce,[39] Lovelady[40] and Virginia Baker (Rackley).[41]

- ↑ Notes from his Dallas police interview placed Oswald on the first floor eating lunch at "about that time";[44] he was on the second floor when a uniformed officer confronted him "90 seconds later".[45]

- ↑ Elaborating for No More Silence, Altgens said, "The explanation given which looks like a forward impact I think is really unexplainable. I don't know whether it's a body reaction or what it was because, from my vantage point, it was very clear he moved forward and didn't move backward."[54]

- ↑ Connally had been seated in the limousine in front of Kennedy and was wounded during the gunfire in Dealey Plaza.

- ↑ As printed on the back cover of the book's jacket, Altgens called Pictures a "powerful display of words and pictures graphically illustrating one of the most tragic moments in the history of the United States. Actual photographs, eyewitness reports, and the author's standard of thoroughness qualify this book as a 'must read' chronicle of the real event taking place that fateful day."

- ↑ In a 1991 letter to author Richard B. Trask, Altgens wrote, "Until those people come up with solid evidence to support their claims, I see no value in wasting my time with them."

- ↑ When Lovelady died in January 1979 at age 41, his attorney told United Press International that Lovelady's resemblance to Oswald led to his client being "hounded out of Dallas" by conspiracy theorists, and that 15 years of strain might have contributed to his death.[63]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Trask 1994, p. 307.

- 1 2 "James Altgens". AP News Archive. Associated Press. December 15, 1995. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ↑ Journalists Remember ... 1993, 1:52:48.

- ↑ Johnson, Robert (November 23, 1983). "Assassination Numbed a Nation". The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington). p. 6. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Trask 1994, p. 318.

- 1 2 Associated Press (May 24, 1964). "'Most Controversial Photo of Decade' Is Published". Sarasota, Florida. Retrieved December 28, 2014 – via Sarasota Herald-Tribune, p. 2.

- 1 2 Journalists Remember ... 1993, 1:52:58.

- 1 2 Associated Press (December 3, 1963). "Pictured Man Is Not Killer". Cumberland, Maryland. Retrieved December 28, 2014 – via Cumberland Evening Times, p. 2.

- ↑ Trask 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Pierce, Arthur C. (1960). Beyond the Time Barrier. American International Pictures.

- ↑ Pierce 1960, 1:14:00 (final line of dialogue).

- ↑ The American Film Institute (1976). American Film Institute Catalog: Feature Films 1961–1970. Vol. 1, Part 2 (hardcover ed.). University of California Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-520-20970-2.

- ↑ Trask 1998, p. 75.

- ↑ Trask 1994, p. 308.

- 1 2 Trask 1994, pp. 308–9.

- ↑ WCH 1964, James W. Altgens, Vol. VII p. 516.

- 1 2 WCH 1964, James W. Altgens, Vol. VII p. 517.

- ↑ Trask 1994, pp. 318–9.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Lyndal L. Shaneyfelt. Vol. V p. 158.

- ↑ Trask 1994, pp. 315–6.

- ↑ Trask 1994, pp. 316.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. II pp. 138–40.

- ↑ Hill & McCubbin 2013, p. 27.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Vol. V p. 180.

- ↑ Hill & McCubbin 2013, p. xi.

- ↑ WCH 1964, James W. Altgens, Vol. VII p. 519.

- ↑ Trask 1998, p. 70.

- ↑ Pett, Saul; Moody, Sid; Mulligan, Hugh; et al., eds. (1963). The Torch Is Passed: The Associated Press Story of the Death of a President, John F. Kennedy (hardcover ed.). Associated Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-86101-568-9.

- 1 2 WCH 1964, James W. Altgens, Vol. VII pp. 522–3.

- ↑ WCH 1964, CE 1407 – FBI report dated June 5, 1964, of interview of James W. Attgens, who took photographs showing Billy Nolan ... Vol. XXII p. 790.

- 1 2 Sneed 1998, p. 52.

- ↑ WCH 1964, James W. Altgens, Vol. VII p. 515-23.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. XXII, pp. 793–4.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. II p. 233.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. III p. 202.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. III p. 189.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. XXII p. 675.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. XXII p. 673.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. VI p. 367.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. VI p. 338.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. VII p. 515.

- ↑ WCH 1964, CE 1381 – Signed statements obtained from all persons known to have been in the Texas School Book Depository Building on ... Vol. XXII p. 84.

- ↑ The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (Warren Commission) (1964). The Report of The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. p. 149.

- ↑ WCH 1964, Vol. XXIV p. 265.

- ↑ Frontline 1993.

- ↑ HSCA 1978, Appendix Vol. VI: Photographic Evidence; Ch. IV:B:3:g: Comparison of Photographs of Lee Harvey Oswald and Billy Nolan Lovelady With That of a Motorcade Spectator pp. 286–93.

- ↑ Knuth, Magen (adjunct instructor, American University). "Was Lee Oswald Standing In the Depository Doorway?". Kennedy Assassination Home Page. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ↑ Assassination of President Kennedy 2012, McKnight, Gerald (professor emeritus, Hood College): 1:31:05–1:31:51.

- ↑ Hayden, Tyler (November 20, 2013). "Oswald Innocence Campaign Descends on Santa Barbara". Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ Marrs, Jim (2013). Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy (e-book ed.). Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-465-05087-1.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 22, 1963). "Kennedy Dead: Is Shot In Dallas". Ludington Daily News (Ludington, Michigan). Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ Altgens, James (November 25, 1963). "Photographer Near Car Saw It All". Pacific Stars and Stripes (Associated Press). p. 23. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ↑ WCH 1964, James W. Altgens. Vol. VII pp. 517–8.

- ↑ Sneed 1998, p. 55.

- ↑ "CBS News Inquiry: The Warren Report". CBS News. August 24, 1967. Retrieved December 29, 2014 – via Congressional Record–House, p. 24057.

- 1 2 Trask 1994, pp. 321–2.

- ↑ Sneed 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Trask 1994, p. 322, fn. 3.

- ↑ Trask 1994, p. 307–22.

- ↑ Journalists Remember ... 1993, 1:56:29–1:56:56.

- ↑ Journalists Remember ... 1993, 1:55:30.

- ↑ Sneed 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ UPI 1979.

- ↑ Sneed 1998, p. 53.

- ↑ "Photographer of JFK, wife found dead". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 6, 1999.

- ↑ Pace, Eric (December 17, 1995). "James Altgens, photographer at Kennedy assassination, dies at 76". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

Bibliography

- The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (Warren Commission) (1964). Warren Commission Hearings and Exhibits. United States Government Printing Office – via Mary Ferrell Foundation. Cited as WCH 1964.

- United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (1978). House Select Committee Hearings and Appendices. United States Government Printing Office – via History Matters. Cited as HSCA 1978.

- "He Looked Like Kennedy's Assassin, and It Hounded Him Until His Death". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International. January 19, 1979. p. B15. Cited as UPI 1979.

- "Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?". Frontline (transcript of broadcast). PBS. November 16, 1993. Retrieved January 19, 2014. Cited as Frontline 1993.

- Journalists Remember the JFK Assassination (video). C-SPAN. November 20, 1993. Retrieved March 18, 2014. Cited as Journalists Remember ... 1993.

- Trask, Richard B. (1994). Pictures of the Pain: Photography and the Assassination of President Kennedy (hardcover ed.). Yeoman Press. ISBN 0-9638595-0-1. Cited as Trask 1994.

- Trask, Richard B. (1998). That Day In Dallas: Three Photographers Capture On Film the Day President Kennedy Died (paperback ed.). Yeoman Press. ISBN 0-9638595-2-8. Cited as Trask 1998.

- Sneed, Larry A. (1998). "James W. Altgens: Eyewitness". No More Silence: An Oral History of the Assassination of President Kennedy. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. pp. 41–59. ISBN 9781574411485. Cited as Sneed 1998.

- Assassination of President Kennedy: Historians talked about the numerous theories that have persisted ... (video). C-SPAN. September 21, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2014. Cited as Assassination of President Kennedy 2012.

- Hill, Clint; McCubbin, Lisa (2013). Five Days in November (hardcover ed.). Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1-476-73149-0. Cited as Hill & McCubbin 2013.

Further reading

- The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (Warren Commission) (1964). "Testimony of James W. Altgens". Warren Commission Hearings (WCH) VII. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 515–25.

External links

- AP Explore: JFK Assassination 50th anniversary (Associated Press—includes images of Altgens' original AP bulletin with handwritten notes)

- JFK Remembered: That Awful Day (Abilene Reporter-News—includes images by and of Altgens, and a 2013 snapshot of his initial AP bulletin)

- Records of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Collection: Key Persons Files: Altgens, James W. (National Archives and Records Administration)

| ||||||||||||||||||||