Limbu language

| Limbu | |

|---|---|

| ᤕᤰᤌᤢᤱ ᤐᤠᤴ yakthung pān | |

| Region | Nepal; significant communities in Bhutan; Sikkim and Darjeeling district of India |

| Ethnicity | Limbu people |

Native speakers | 380,000 (2011 census)[1] |

|

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Dialects |

Phedape, Chhathare, Tambarkhole & Panthare

|

| Limbu script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Sikkim, India |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

lif |

| Glottolog |

limb1266[2] |

Limbu is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Nepal, India (Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Sikkim, Assam, and Nagaland), Bhutan, Burma, Thailand, UK, Hong Kong, Canada, and USA. It is falsely believed that Limbus/Yakthungs are multi-lingual, but there are hundred and/or thousand of Yakthungs who speak only in Yakthungpan (Limbu language). Limbus refer to themselves as Yakthung and their language as Yakthungpan. Yakthungpan has four main dialects such as Phedape, Chhathare, Tambarkhole, and Panthare dialects. The theoretical concept of four major Yakthungpan dialects is much more ideological because scholars, writers, and linguists have not yet done scientific research on the Yakthungpan, spoken in Sikkim, Bhutan, Assam, Burma, and Thailand. Meaning, there can be definitely more than four Yakthungpan dialects. To officially announce that there are only four major major Yakthung dialects is a blindspot of ideological and political thinking without doing proper research in other Yakthungpan speaking communities such as in India, Bhutan, and Thailand (and even beyond).

Among four dialects and/or many dialects, Phedape dialect is widely spoken and well understood by most Yakthungpan speakers. However, as there are some dominant Panthare scholars who have role to create knowledge and control knowledge in the Limbu communities, Panthare dialect is being popularized as a "standard" Limbu language. As Panthare Yakthungs are much more engaged in central political position and administrative positions, they are trying to introduce Panthare dialect as a Standard Yakthungpan.

Yakthungpan (Limbu language) is one of the major languages spoken and written in Nepal, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Sikkim, Bhutan, Burma, and Thailand. Today, linguists have reached the conclusion that Yakthungpan resembles Tibetan and Lepcha.

Before the introduction of Sirijanga script among Limbu Kiratas, Rong script was popular in East Nepal specially in early Maurong state. Sirijanga script had almost disappeared for 800 years and it was brought into practice again by Tey-Angsi Sirijunga Xin Thebe of Tellok Sinam.

Sirijanga

Limbu, Lepcha and Newari are the only Sino-Tibetan languages of the Central Himalayas to possess their own scripts (Sprigg 1959: 590), (Sprigg 1959: 591-592 & MS: 1-4) tells us that the Kiranti or Limbu script was devised during the period of Buddhist expansion in Sikkim in the early 18th century when Limbuwan still constituted part of Sikkimese territory. The Kiranti script was probably designed roughly at the same time as the Lepcha script (during the reign of the third King of Sikkim, Phyag-dor Nam-gyal (ca. 1700-1717)). However, it is widely believed that the Kiranti (Sirijanga) script had been designed by the King Sirijanga in the 9th century. The Sirijanga script was later designed by Tey-Angsi Singthebe. As Te-onsi Singthebe spent most of his time in the development of Yakthungpan, Yatkhung culture, and Sirijanga script, he is considered as the reincarnation of the King Sirijanga.

As Te-ongsi Singthebe was astoundingly influential person to spread Yakthung script, culture, and language, Tasong monks feared him. Tasong monks feared that Tey-Angsi might transform the social, cultural, and linguistic structure of Sikkim. Therefore, Tasong monks caputured Te-ongsi, bound on a tree, and shot to death with poisonous arrows.

Both Kiranti and Lepcha were ostensibly devised with the intent of furthering the spread Buddhism. However, Sirijanga was a Limbu Buddhist who had studied under Sikkimese high Lamas. Sirijanga was given the title 'the Dorje Lama of Yangrup'.

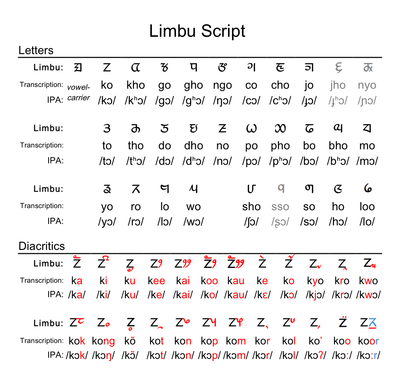

The language and script's influential structure are mixture of Tibetan and Devanagari. Unlike most other Brahmic scripts, it does not have separate independent vowel characters, instead using a vowel carrier letter with the appropriate dependent vowel attached.

The Limbu language and literature has been less practiced in Nepal since the last eighteenth century. The cultural identity of any community was taken as a threat to the national unification by ruling elites until the recent years. The use of Limbu alphabets was banned and the possession of Limbu writings outlawed. There were no specific laws about it, but the Security Act was enforced for such cases under the strong directives of Kathmandu.

Writing

Limbu has its own unique writing system, which is similar to Tibetan and Sikkimese scripts. The Sirijanga script is unique and scientifically designed by King Sirijanga in the 9th century; it was later re/designed and popularized by Tey-Angsi Thebe and his cronies in the 18th century. Since teaching of Limbu/Yakthung language and writing was banned by the Khas-Hindus in Nepal after the "Noon Pani Sandhi" between the Limbuwan and Gorkha Kingdom (Prithvi Narayan Shah), far more Limbus are literate in Nepali than in Limbu in Nepal. Although many Limbu books were written in Devanagari and Roman (English), now Limbus/Yakthungs have well developed computerized writing system and many books are published in Sirijanga script.

History of Limbu writing can be divided into the following ways:

Historical Development of Yakthung rhetoric and writing:

1. Classical Susuba Lilim Yakthunghang period: King Sirijanga and his cronies (9th century AD) 2. Medieval Susuba Lilim Yakthunghang period: Tey-Angsi Thebe and his cronies (18th century AD Limbuwan (includes Limbuwan and Sikkim) movement. 3. Modern Period:

First Generation Limbu writers and rhetors: Period of Jobhansing Phago, Chyangresing Phedangba, Ranadwaj Yakthung, and Ranjit Yakthung (Brian Hudgson’s manuscript collection period)

Second Generation Limbu writers and rhetors: i. After the establishment of “Yakthunghang Chumlung” (1924); thereafter, several books were published. ii. Limbu script was much more influenced by Devnagari script at this period. iii. At the same time, both national and international linguists, researchers, and writers addressed the issued in this period. This period is period of inquiry, communication, discovery, and re/construction.

Third Generation Limbu writers and rhetors: This period denotes after the restoration of democracy in Nepal in 1990. Introduction of “Anipan” at school; many research and writing such as MA/MPhil theses and research reports; establishment of Limbu organization at the local and global level; period of delinking, relinking, and linking epistemologies.

Publications

Limbu language has many papers and publications in circulation. Tanchoppa ( Morning Star ), a monthly newspaper/magazine published since 1995. There are many other literary publications. The oldest known Limbu writings were collected from Darjeeling district in 1850's. They are the ancestors of the modern Limbu script. The writings are now a part of collection in India Library in London.

Teaching

In Nepal, the Limbu language is taught on private initiative. The Government of Nepal has published " Ani Paan" text books in Limbu for Primary education from grades 1 to 5. Kirant Yakthung Chumlung teaches Limbu language and script in its own initiative.

In Sikkim, since late 1970s Limbu, in Limbu script has been offered in English medium schools as a vernacular language subject in areas populated by Limbus. Over 4000 students study Limbu for one hour daily taught by some 300 teachers. Course books are available in Limbu from grades 1 to 12.

See also

References

- Driem, George van (1987). A grammar of Limbu. (Mouton grammar library; 4). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-011282-5

External links

| Limbu language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Omniglot modern Limbu writing system

- Limbu-English Dictionary of the Mewa Khola dialect (PDF introduction)

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||