Chukchi language

| Chukchi | |

|---|---|

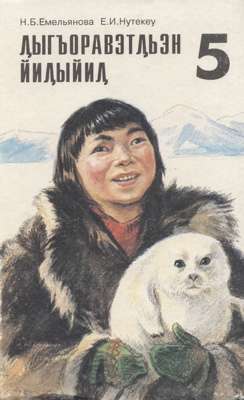

|

Ԓыгъоравэтԓьэн йиԓыйиԓ Lyg'oravetl'en jilyjil | |

| Pronunciation | [ɬǝɣˀorawetɬˀɛn jiɬǝjiɬ] |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Chukotka Autonomous Okrug |

| Ethnicity | 15,900 Chukchi (2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 5,100 (2010 census)[1] |

|

Chukotko-Kamchatkan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

ckt |

| Glottolog |

chuk1273[2] |

Chukchi /ˈtʃʊktʃiː/[3] (Chukchee) is a Palaeosiberian language spoken by Chukchi people in the easternmost extremity of Siberia, mainly in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. According to the Russian Census of 2002, about 7,700 of the 15,700 Chukchi people speak Chukchi; knowledge of the Chukchi language is decreasing, and most Chukchis now speak the Russian language (fewer than 500 report not speaking Russian at all). Chukchi is closely related to Koryak, which is spoken by about half as many as speak Chukchi. The language, together with Koryak, Kerek, Alutor, and Itelmen, forms the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family.

The Chukchi and Koryaks form a cultural unit with an economy based on reindeer herding, and both have autonomy within the Russian Federation.

The ethnonym Chukchi or Chukchee is an Anglicized form of the Russian ethnonym (singular Chukcha, plural Chukchi). This came into Russian from Čävča, the term used by the Chukchis' Tungusic-speaking neighbors, itself a rendering of the Chukchi word [tʃawtʃəw], which in Chukchi means "a man who is rich in reindeer". The Chukchis' term for themselves is [ɬəɣʔorawetɬʔat] (singular [ɬəɣʔorawetɬʔan]), "the real people".

In the UNESCO Red Book, the language is on the list of endangered languages.

Scope

Many Chukchis use the language as their primary means of communication both within the family and while engaged in their traditional pastoral economic activity (reindeer herding). The language is also used in media (including radio and TV translations) and some business activities. However, Russian is increasingly used as the primary means of business and administrative communication, in addition to behaving as a lingua franca in territories inhabited by non-Chukchis such as Koryaks and Yakuts. Almost all Chukchis speak Russian, although some have a lesser command than others. Chukchi language is used as a primary language of instruction in elementary school; the rest of secondary education is done in Russian with Chukchi taught as a subject.

A Chukchi writer, Yuri Rytkheu (1930–2008), has earned a measure of renown in both Russia and Western Europe, although much of his published work was written in Russian, rather than Chukchi.

Orthography

Until 1931, the Chukchi language had no official orthography, in spite of attempts in the 1800s to write religious texts in it.

At the beginning of the 1900s, Vladimir Bogoraz discovered specimens of pictographic writing by the Chukchi herdsman Tenevil (see ru:File:Luoravetl.jpg). Tenevil's writing system was his own invention, and was never used beyond his camp. The first official Chukchi alphabet was devised by Bogoraz in 1931 and was based on the Latin script:

| А а | Ā ā | B b | C c | D d | Е е | Ē ē | Ə ə |

| Ə̄ ə̄ | F f | G g | H h | I i | Ī ī | J j | K k |

| L l | M m | N n | Ŋ ŋ | O o | Ō ō | P p | Q q |

| R r | S s | T t | U u | Ū ū | V v | W w | Z z |

| Ь ь |

In 1937, this alphabet, along with all of the other alphabets of the non-Slavic peoples of the USSR, was replaced by a Cyrillic alphabet. At first it was the Russian alphabet with the addition of the digraphs К’ к’ and Н’ н’. In the 1950s the additional letters were replaced by Ӄ ӄ and Ӈ ӈ. These newer letters were mainly used in educational texts, while the press continued to use the older versions. At the end of the 1980s, the letter Ԓ ԓ was introduced as a replacement for Л л. This was intended to reduce confusion with the pronunciation of the Russian letter of the same form. The Chukchi alphabet now stands as follows:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Ӄ ӄ | Ԓ ԓ (Л л) | М м | Н н |

| Ӈ ӈ | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я | ' |

Phonology

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||

| Stop | p | t | k | q | ʔ | |||||||

| Fricative | β | ɬ | ç | ɣ | ||||||||

| Approximant | ɹ | j | ||||||||||

There are no voiced stops in the language.

The vowels are /i/, /u/, /e1/, /e2/, /o/, /a/, and /ə/. /e1/ and /e2/ are pronounced identically but behave differently in the phonology. (Cf. the two kinds of /i/ in Inuit Eskimo, whose known cause is the merger of two vowels /i/ and /ə/, which are still separate in Yup'ik Eskimo.)

A notable feature of Chukchi is its vowel harmony system largely based on vowel height. /i, u, e1/ alternate with /e2, o, a/, respectively. The second group is known as "dominant vowels" and the first group as "recessive vowels"; that is because whenever a "dominant" vowel is present anywhere in a word, all "recessive" vowels in the word change into their "dominant" counterpart. The schwa vowel /ə/ does not alternate but may trigger harmony as if it belonged to the dominant group.

Initial and final consonant clusters are not tolerated, and schwa epenthesis is pervasive.

Stress tends to: 1. be penultimate; 2. stay within the stem; 3. avoid schwas.

Grammar

Chukchi is largely agglutinative and has ergative–absolutive alignment. It also has very pervasive incorporation.

In the nominals, there are two numbers and about nine grammatical cases (absolutive, ergative, instrumental, locative, ablative, allative, orientative, two comitatives and a designative). Nouns are split into three declensions influenced by animacy: the first declension, which contains non-humans, has plural marking only in the absolutive case; the second one, which contains personal names and certain words for mainly older relatives, has obligatory plural marking in all forms; the third one, which contains other humans than those in the second declension, has optional plural marking.

Verbs distinguish three persons, two numbers, three moods (declarative, imperative and conditional), two voices (active and antipassive) and six tenses: present I (progressive), present II (stative), past I (aorist), past II (perfect), future I (perfective future), future II (imperfective future). It is interesting that past II is formed with a construction meaning possession (literally "to be with"), similar to the use of "have" in the perfect in English and other Western European languages.

Both subject and direct object are cross-referenced in the verbal chain, and person agreement is very different in intransitive and transitive verbs. Person agreement is expressed with a complex system involving both prefixes and suffixes; despite the agglutinative nature of the language, each individual combination of person, number, tense etc. is expressed in a way that is far from always straightforward. Besides the finite forms, there are also infinitive, supine (purposive), numerous gerund forms, and a present and past participle, and these are all used with auxiliary verbs to produce further analytic constructions.

The numeral system was originally purely vigesimal and went up to 400, but a decimal system was introduced for numerals above 100 via Russian influence. Many of the names of the basic numbers can be traced etymologically to words referring to the human body ("finger", "hand" etc.) or to arithmetic operations (6 = "1 + 5" etc.).

The word order is rather free, though SOV is basic. The possessor normally precedes the possessed, and postpositions rather than prepositions are used.

External influence

The external influences of Chukchi have not been well-studied. In particular, the degree of contacts between the Chukchi and Eskimo languages remains an open question. Research into this area is problematic in part because of the lack of written evidence. (Cf. de Reuse in the Bibliography.) Contact influence of Russian, which is increasing, consists of word borrowing and pressure on surface syntax; the latter is primarily seen in written communication (translated texts) and is not apparent in day-to-day speech.

Bibliography

- Alevtina N. Zhukova, Tokusu Kurebito,"A Basic Topical Dictionary of the Koryak-Chukchi Languages (Asian and African Lexicon Series, 46)",ILCAA, Tokyo Univ. of Foreign Studies (2004), ISBN 978-4872978964

- Bogoras, Waldemar, 1901. "The Chukchi of Northeastern Asia", American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Jan–Mar, 1901), pp. 80–108

- Bogoras, W., 1922. "Chukchee". In Handbook of American Indian Languages II, ed. F. Boas, Washington, D.C.

- Comrie, B., 1981. The Languages of the Soviet Union, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Language Surveys). ISBN 0-521-23230-9 (hardcover) and ISBN 0-521-29877-6 (paperback)

- De Reuse, Willem Joseph, 1994. Siberian Yupik Eskimo: The Language and Its Contacts with Chukchi, Univ. of Utah Press, ISBN 0-87480-397-7

- Dunn, Michael, 2000. "Chukchi Women's Language: A Historical-Comparative Perspective", Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Fall, 2000), pp. 305–328

- Nedjalkov, V. P., 1976. "Diathesen und Satzstruktur im Tschuktschischen" [in German]. In: Ronald Lötzsch (ed.), Satzstruktur und Genus verbi (Studia Grammatica 13). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, pp. 181–211.

- Priest, Lorna A. (2005). "Proposal to Encode Additional Cyrillic Characters" (PDF).

- Skorik, P[etr] Ja., 1961. Grammatika čukotskogo jazyka 1: Fonetika i morfologija imennych častej reči (Grammar of the Chukchi Language: Phonetics and morphology of the nominal parts of speech) [in Russian]. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Skorik, P[etr] Ja., 1977. Grammatika čukotskogo jazyka 2: Glagol, narečie, služebnye slova (Grammar of the Chuckchi Language: Verb, adverb, function words) [in Russian]. Leningrad: Nauka:

- Weinstein, Charles, 2010. Parlons tchouktche [in French]. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-10412-9

External links

| Chukchi language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Spencer, Andrew (1999). "Chukchee homepage [Grammatical sketch based on Skorik 1961-1977]".

- Muravyova I. A., Daniel M. A., Zhdanova T. Ju. (2001). "Chukchi language and folklore in texts collected by V. G.Bogoraz. Part two: grammar".

- Endangered Languages of Siberia – The Chukchi language

- Russian-Chukchi Phrasebook

- Chukchi fairy tales in Chukchi and English

- The Gospel of Luke in Chukchi

- A Chukchi language appendix to the newspaper "Krayny Sever"

- Population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia in 1897

- Siegel, Wolfram. "Chukchi (Луоравэтлан/Luoravetlan)". Omniglot.

- Volodin, A. P. and P. Ja. Skorik (1997). "Čukotskyj jazyk" (The Chukchi language) [in Russian]. In: Jazyki mira: Paleoaziatskije jazyki (Languages of the World: Paleoasiatic Languages), Moskva: Indrik, p. 23-39; online: "Čukotskyj jazyk".

- Skorik, P. J. (1961/1977). Grammatika čukotskogo jazyka (Grammar of the Chukchi Language) [in Russian]. Vol. 1/2. Leningrad: Nauka

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|