Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy screening

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in young athletes. HCM is frequently asymptomatic until SCD, and thus its prevention requires screening. Screening by medical history and physical exam are ineffective, indicating heart abnormalities in only 3% of patients who subsequently suffered SCD. However, HCM can be detected with 80%+ accuracy by echocardiograms, which may be combined with pre-screening by electrocardiograms (ECGs). Routine cardiac screening of athletes has been implemented in Italy since the 1970s, and has resulted in an 89% drop in cases of SCD among screened athletes. In the United States, the American Heart Association has "consistently opposed" such routine screening. (See (Sanghavi 2009) for a popular summary of literature and discussion). However certain chapters of the American College of Cardiology are backing screening models provided by private entities and nonprofit organizations.

Description

HCM is a genetic disorder that causes the muscle of the heart (the myocardium) to thicken (or hypertrophy) without any apparent reason. When the heart thickens and becomes enlarged, particularly at the septum and left ventricle, it can cause dangerous arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms). The thickening of the heart makes it harder for blood to leave, forcing the heart to work more vigorously to pump blood.

HCM occurs in up to two per 1000 people in the general population, being a primary and familial malformation. While younger individuals are likely to have a more severe form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the condition is seen in people of all ages. Studies have shown that HCM is generally regarded as the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in athletes, accounting for 36% of deaths. Almost half of deaths in HCM happen during or just after the patient has done some type of physical activity. Sudden death is frequently the first indication of the presence of HCM, where 90% of deaths in athletes occur in males. This is potentially due to the higher frequency of participation at a higher intensity in male athletics. 60% of athletes are of high school age at the time of death.

The first symptom of HCM among very young patients tends to be sudden collapse and possible death. However, other symptoms include exertional dyspnea (most common), chest pain, dizziness, fainting, high blood pressure (hypertension), heart palpitations, fatigue and shortness of breath. However, some patients have no symptoms and may not realize they have the condition until it is found during a routine medical exam.

Athlete's heart vs. HCM

Quite often, HCM can be mistaken for a condition known as athlete’s heart. Both involve growth of the myocardium, however the latter generally is not correlated with incidences of SCD. While HCM can be linked to family history, athlete’s heart arises purely as a function of intense exercise (usually at least an hour every day). Since the body is operating at high training levels, the heart adapts and grows in order to pump blood more efficiently. Stoppage of exercise for three months generally leads to a decrease in wall/septum thickness in those with athlete’s heart, whereas those with HCM exhibit no decline.

People with athlete’s heart do not exhibit an abnormally enlarged septum, and the growth of heart muscle at the septum and free ventricular wall is symmetrical. The asymmetrical growth seen in HCM results in a less-dilated left ventricle. This in turn leads to a smaller volume of blood leaving the heart with each beat.

| Athlete's Heart | HCM | |

|---|---|---|

| Septum thickness | <15 mm | >15 mm |

| Symmetry | Yes (for septum and LV wall) | No (septum much thicker |

| Family history | None | Possibly |

| Deconditioning | Reduction within 3 months | None |

Screening and Diagnosis

Screening young athletes to detect HCM is an essential process in preventing a possible sudden cardiac death as most at victims do not show prior symptoms. Rarely HCM can induce symptoms like dyspnea (difficulty breathing) or chest pain that are related to the aforementioned heart defect. However the subsequent abnormalities of HCM like myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, will likely be asymptomatic and those at risk will likely never know unless screened and diagnosed by a medical doctor.

Most medical professions and researchers agree that there are three methods of screening for HCM and sudden cardiac death, each with their own benefits and weaknesses:

- Physical examination and medical history is ineffective, catching only 3% of cases;

- ECGs detect heart abnormalities and detect 70% of asymptomatic HCM, but cannot specify that the abnormality is specifically HCM;

- Echocardiograms detect 80%+ of HCM, and are used to diagnose HCM specifically – the correct diagnosis of HCM is always made by using an echocardiogram.

1) Physical Examination and Medical History

Defined: Refers to a thorough but general physical examination that most patients / athletes would receive at any check-up with their doctor. This method of screening looks for some of the symptoms mentioned above as well as heart palpitations or unusual chest X-rays. In addition, the existence of diseased family members that may have suffered from sudden cardiac death is important because of the genetic transfer of the disease. This is the method used in most United States school sports and youth organizations.

While cheap and easily performed by trained medical staff (doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, paramedics and EMTs, trained medical and nursing students, and certain other medical and allied health professionals and paraprofessionals, as allowed by their profession and agency, and state and federal regulations) it is impossible for a physical examination and medical history screening to detect the disease HCM and is therefore unreliable.

2) 12 Lead Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Defined: Is a test performed by a doctor or trained health professional to measure the electrical signals produced by the heart. The ECG cannot be used to directly detect HCM but is useful in detecting general heart abnormalities to subsequently recommend further testing, such as echocardiography. Even an asymptomatic patient will demonstrate an abnormal ECG in 70% of cases. Although extra costs are associated with the equipment and professional assistance, it is an effective method of screening when used as a referral for echocardiography screening. The advantages: it is a relatively cheap and non-invasive, somewhat routine cardiovascular test that can be performed by a variety of persons with the requisite training, which just requires knowledge of anatomy and physiology, cardiac anatomy and physiology and pathology, basic first aid, the cardiac cycle and electrical conduction (normal rhythm), abnormal rhythms (arrhythmias), the machine and proper lead placement (which are not extremely complicated and are taught early to many health students, using simpler versions, in a lab). There is some support for using a physical examination and ECG as a baseline screening for athletes as a means to refer abnormal cases to definitive diagnoses of problems and to clear those with normal results. However, insurance may not cover such screening; sometimes, schools have organizations or groups of health students or professionals conduct them on a discounted or pro bono basis.

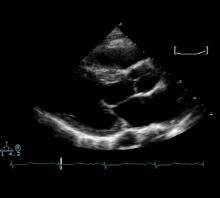

3) Echocardiography (ECHO)

|

Example of Echocardiogram

Echocardiogram |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Defined: A Transthoracic Echocardiogram provides a 2-D image to a doctor from standard ultrasound that is directly and reliably able to detect HCM in athletes. This procedure is expensive but is considered to be optimally used when implemented after an abnormal ECG and is the only test of choice to confirm a diagnosis. Studies indicate that doctors are able to detect HCM from an ECHO anywhere from 80% to 100% of the time.

A full ECHO may cost $400–$1,000 in the United States, but a targeted ECHO for HCM screening may be performed in 2.5 minutes at a cost of $35, as is done by Purdue University.[1]

Successful models of intervention using ECG

As previously discussed, ECG screening appears to be the most feasible and effective method for screening for HCM. There are contrasting policies with regards to national standards on screening young athletes for cardiovascular abnormalities. Below are a few successful interventions, followed by the United States’ approach.

Italy

By law, all competitive athletes are required to undergo physiological testing prior to competing. This consists of a history, physical examination, urinalysis, resting and exercise ECG, and pulmonary functioning test. All of these are conducted by a sports physician. If there are abnormalities, further screening of ECHO (echocardiography) is required.

- A study of 4,050 Italian national team athletes revealed high levels of efficiency of 12-lead ECG in detecting HCM in young athletes. Athletes with HCM were not allowed to compete.

- Trends in cases of sudden death in screened and unscreened athletes were monitored over 25 years. Sudden cardiovascular death accounted for 55 deaths in screened athletes and 265 in unscreened athletes. Overall, there was an 89% decrease in incidence of athlete death due to cardiovascular abnormalities.

European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention in Sports Cardiology

This is supported by the International Olympic Committee, and follows the Italian strategy, with personal and family history, physical examination, and 12-lead resting ECG. FIFA also performed preparticipation screening of all soccer players in the world championships in Germany in 2006.

United States

As of 2014 there was no national policy for the screening of CVD or sudden cardiac death in young athletes, though many screening programs were being run by private entities and various non profit organizations. Most state laws require competitive athletes to undergo a physician-mediated physical examination and history. ECG or echocardiograms are rarely used. A medical history and physical examination were found to have little sensitivity or power to detect HCM or other risk conditions. It is considered that routine screening is not justified due to the low incidence of HCM, approximately 2 in 1,000 individuals.

References

- ↑ Following Their Hearts, David Hill, Training & Conditioning, 16.2, March 2006

1. Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical Sports Medicine 3rd Edition. (2007) McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd.

2. Corrado et al. (2006). Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. Journal of the American Medical Association. 296: 1593-1601.

3. Doemico, C., Basso, C., Shiavon, M., Thiene, G. (1998). Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopthay in young athletes. N Engl J Med. 339. 6, 364-369.

4. FIFA. Prevention the priority for FIFA medical division. http://fifaworldcup.yahoo.com/06/en/050625/1/4ul.html (25 June 2005).

5. Fuller, C.M. (2000). Cost effectiveness analysis of screening high school athletes for risk of sudden cardiac death. Med & Sci Sp Ex. 32. 5, 887-890.

6. Futterman LG, Myerburg R. Sudden death in athletes: an update. Sports Med. 1998;26:335–350.

7. International Olympic Committee. Sudden cardiovascular death in sport. Lausanne, Switzerland. http://www.olympic.org/uk/news/Olympic_news/newsletter_full_story_ukasp?id=1182 Lausanne recommendations adopted 9–10 December 2004.

8. Maron BJ (Mar 2002). "Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review". JAMA 287 (10): 1308–20.

9. Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Practical steps for preventing sudden death. Physician Sportsmed 2002; 30(1): 19-24.

10. Maron, B.J. et al. (2003). Sudden Death in Young Athletes. N Engl J Med. 349. 1064-1075.

11. Maron, B.J., Shirani, J., Poliac, L., et al. (1996). Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, Demongraphic and pathological profiles. Journal of American Medical Association, 276. 3. 199-204.

12. Maron, B.J., Thompson, P.D. (2002). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Physician and Sports Medicine, 30. 1. 127-133.

13. Pellicia et al. (2008). Outcomes in athletes with marked ECG repolarization abnormalities. New England Journal of Medicine. 358: 152-161.

14. Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, et al. (Mar 1996). "Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies". Circulation 93 (5): 841–2.

15. Wight JN, Jr, Salem D. Sudden cardiac death and the “athlete's heart.” Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1473–1480.

- Sanghavi, Darshak (February 3, 2009), "Dying To Play: Why don't we prevent more sudden deaths in athletes?", Slate.com