Hyperbolic angle

In mathematics, a hyperbolic angle is a geometric figure that divides a hyperbola. The science of hyperbolic angle parallels the relation of an ordinary angle to a circle. The hyperbolic angle is first defined for a "standard position", and subsequently as a measure of an interval on a branch of a hyperbola.

A hyperbolic angle in standard position is the angle at (0, 0) between the ray to (1, 1) and the ray to (x, 1/x) where x > 1.

The magnitude of the hyperbolic angle is the area of the corresponding hyperbolic sector which is ln x.

Note that unlike circular angle, hyperbolic angle is unbounded, as is the function ln x, a fact related to the unbounded nature of the harmonic series. The hyperbolic angle in standard position is considered to be negative when 0 < x < 1.

Suppose ab = 1 and cd = 1 with c > a > 1 so that (a, b) and (c, d) determine an interval on the hyperbola xy = 1. Then the squeeze mapping with diagonal elements b and a maps this interval to the standard position hyperbolic angle that runs from (1, 1) to (bc, ad). By the result of Gregoire de Saint-Vincent, the hyperbolic sector determined by (a, b) and (c, d) has the same area as this standard position angle, and the magnitude of the hyperbolic angle is taken to be this area.

The hyperbolic functions sinh, cosh, and tanh use the hyperbolic angle as their independent variable because their values may be premised on analogies to circular trigonometric functions when the hyperbolic angle defines a hyperbolic triangle. Thus this parameter becomes one of the most useful in the calculus of a real variable.

Comparison with circular angle

A unit circle  has a circular sector with an area half of the circular angle in radians. Analogously, a unit hyperbola

has a circular sector with an area half of the circular angle in radians. Analogously, a unit hyperbola  has a hyperbolic sector with an area half of the hyperbolic angle.

has a hyperbolic sector with an area half of the hyperbolic angle.

There is also a projective resolution between circular and hyperbolic cases: both curves are conic sections, and hence are treated as projective ranges in projective geometry. Given an origin point on one of these ranges, other points correspond to angles. The idea of addition of angles, basic to science, corresponds to addition of points on one of these ranges as follows:

Circular angles can be characterised geometrically by the property that the if two chords P0P1 and P0P2 subtend angles L1 and L2 at the centre of a circle, their sum L1 + L2 is the angle subtended by a chord PQ, where PQ is required to be parallel to P1P2.

The same construction can also be applied to the hyperbola. If P0 is taken to be the point (1, 1), P1 the point (x1, 1/x1), and P2 the point (x2, 1/x2), then the parallel condition requires that Q be the point (x1x2, 1/x11/x2). It thus makes sense to define the hyperbolic angle from P0 to an arbitrary point on the curve as a logarithmic function of the point's value of x.[1][2]

Whereas in Euclidean geometry moving steadily in an orthogonal direction to a ray from the origin traces out a circle, in a pseudo-Euclidean plane steadily moving orthogonally to a ray from the origin traces out a hyperbola. In Euclidean space, the multiple of a given angle traces equal distances around a circle while it traces exponential distances upon the hyperbolic line.[3]

Both circular and hyperbolic angle provide instances of an invariant measure. Arcs with an angular magnitude on a circle generate a measure on certain measurable sets on the circle whose magnitude does not vary as the circle turns or rotates. For the hyperbola the turning is by squeeze mapping, and the hyperbolic angle magnitudes stay the same when the plane is squeezed by a mapping

- (x, y) ↦ (rx, y / r), with r > 0 .

History

The quadrature of the hyperbola is the evaluation of the area swept out by a radial segment from the origin as the terminus moves along the hyperbola. It was first accomplished by Gregoire de Saint-Vincent in 1647 in his momentous Opus geometricum quadrature circuli et sectionum coni. As expressed by a historian,

- [He made the] quadrature of a hyperbola to its asymptotes, and showed that as the area increased in arithmetic series the abscissas increased in geometric series.[4]

The upshot was the logarithm function, as now understood as the area under y = 1/x to the right of x = 1. As an example of a transcendental function, the logarithm is more familiar than its motivator, the hyperbolic angle. Nevertheless, the hyperbolic angle plays a role when the theorem of Saint-Vincent is advanced with squeeze mapping.

Circular trigonometry was extended to the hyperbola by Augustus De Morgan in his textbook Trigonometry and Double Algebra.[5] In 1878 W.K. Clifford used the hyperbolic angle to parametrize a unit hyperbola, describing it as "quasi-harmonic motion".

In 1894 Alexander Macfarlane circulated his essay "The Imaginary of Algebra", which used hyperbolic angles to generate hyperbolic versors, in his book Papers on Space Analysis.[6]

When Ludwik Silberstein penned his popular 1914 textbook on the new theory of relativity, he used the rapidity concept based on hyperbolic angle a, where tanh a = v/c, the ratio of velocity v to the speed of light. He wrote:

- It seems worth mentioning that to unit rapidity corresponds a huge velocity, amounting to 3/4 of the velocity of light; more accurately we have v = (.7616)c for a = 1.

- [...] the rapidity a = 1, [...] consequently will represent the velocity .76 c which is a little above the velocity of light in water.

Silberstein also uses Lobachevsky's concept of angle of parallelism Π(a) to obtain cos Π(a) = v/c.[7]

Imaginary circular angle

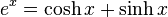

The hyperbolic angle is often presented as if it were an imaginary number. Thus, if x is a real number and i2 = −1, then

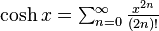

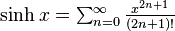

so that the hyperbolic functions cosh and sinh can be presented through the circular functions. But these identities do not arise from a circle or rotation, rather they can be understood in terms of infinite series. In particular, the one expressing the exponential function ( ) consists of even and odd terms, the former comprise the cosh function (

) consists of even and odd terms, the former comprise the cosh function ( ), the latter the sinh function (

), the latter the sinh function ( ). The infinite series for cosine is derived from cosh by turning it into an alternating series, and the series for sine comes from making sinh into an alternating series. The above identities use the number i to remove the alternating factor (−1)n from terms of the series to restore the full halves of the exponential series. Nevertheless, in the theory of holomorphic functions, the hyperbolic sine and cosine functions are incorporated into the complex sine and cosine functions.

). The infinite series for cosine is derived from cosh by turning it into an alternating series, and the series for sine comes from making sinh into an alternating series. The above identities use the number i to remove the alternating factor (−1)n from terms of the series to restore the full halves of the exponential series. Nevertheless, in the theory of holomorphic functions, the hyperbolic sine and cosine functions are incorporated into the complex sine and cosine functions.

Notes

- ↑ Bjørn Felsager, Through the Looking Glass – A glimpse of Euclid's twin geometry, the Minkowski geometry, ICME-10 Copenhagen 2004; p.14. See also example sheets exploring Minkowskian parallels of some standard Euclidean results

- ↑ Viktor Prasolov and Yuri Solovyev (1997) Elliptic Functions and Elliptic Integrals, page 1, Translations of Mathematical Monographs volume 170, American Mathematical Society

- ↑ Hyperbolic Geometry pp 5–6, Fig 15.1

- ↑ David Eugene Smith (1925) History of Mathematics, pp. 424,5 v. 1

- ↑ Augustus De Morgan (1849) Trigonometry and Double Algebra, Chapter VI: "On the connection of common and hyperbolic trigonometry"

- ↑ Alexander Macfarlane(1894) Papers on Space Analysis, B. Westerman, New York

- ↑ Ludwik Silberstein (1914) Theory of Relativity, Cambridge University Press, pp. 180–1

See also

References

- Janet Heine Barnett (2004) "Enter, stage center: the early drama of the hyperbolic functions", available in (a) Mathematics Magazine 77(1):15–30 or (b) chapter 7 of Euler at 300, RE Bradley, LA D'Antonio, CE Sandifer editors, Mathematical Association of America ISBN 0-88385-565-8 .

- Mellon W. Haskell (1895) On the introduction of the notion of hyperbolic functions Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 1(6):155–9.

- Arthur Kennelly (1912) Application of hyperbolic functions to electrical engineering problems

- William Mueller, Exploring Precalculus, § The Number e, Hyperbolic Trigonometry.

- John Stillwell (1998) Numbers and Geometry exercise 9.5.3, p. 298, Springer-Verlag ISBN 0-387-98289-2.