Hydrogen spectral series

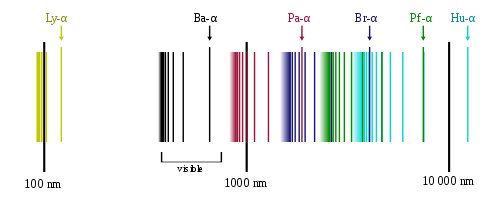

The emission spectrum of atomic hydrogen is divided into a number of the spectral series, with wavelengths given by the Rydberg formula. These observed spectral lines are due to the electron making transitions between two energy levels in the atom. The classification of the series by the Rydberg formula was important in the development of quantum mechanics. The spectral series are important in astronomical spectroscopy for detecting the presence of hydrogen and calculating red shifts.

Physics

A hydrogen atom consists of an electron orbiting its nucleus. The electromagnetic force between the electron and the nuclear proton leads to a set of quantum states for the electron, each with its own energy. These states were visualized by the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom as being distinct orbits around the nucleus. Each energy state, or orbit, is designated by an integer, n as shown in the figure.

Spectral emission occurs when an electron transitions, or jumps, from a higher energy state to a lower energy state. To distinguish the two states, the lower energy state is commonly designated as n′, and the higher energy state is designated as n. The energy of an emitted photon corresponds to the energy difference between the two states. Because the energy of each state is fixed, the energy difference between them is fixed, and the transition will always produce a photon with the same energy.

The spectral lines are grouped into series according to n′. Lines are named sequentially starting from the longest wavelength/lowest frequency of the series, using Greek letters within each series. For example, the 2 → 1 line is called "Lyman-alpha" (Ly-α), while the 7 → 3 line is called "Paschen-delta" (Pa-δ).

There are emission lines from hydrogen that fall outside of these series, such as the 21 cm line. These emission lines correspond to much rarer atomic events such as hyperfine transitions.[1] The fine structure also results in single spectral lines appearing as two or more closely grouped thinner lines, due to relativistic corrections.[2]

Rydberg formula

The energy differences between levels in the Bohr model, and hence the wavelengths of emitted/absorbed photons, is given by the Rydberg formula:[3]

where n is the upper energy level, n′ is the lower energy level, and R is the Rydberg constant (1.097373 × 107 m−1).[4] Meaningful values are returned only when n is greater than n′ and the limit of one over infinity is taken to be zero.

Series

Lyman series (n′ = 1)

The series is named after its discoverer, Theodore Lyman, who discovered the spectral lines from 1906–1914. All the wavelengths in the Lyman series are in the ultraviolet band.[5][6]

| n | λ, vacuum

(nm) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 121.57 |

| 3 | 102.57 |

| 4 | 97.254 |

| 5 | 94.974 |

| 6 | 93.780 |

| ∞ | 91.175 |

Balmer series (n′ = 2)

Named after Johann Balmer, who discovered the Balmer formula, an empirical equation to predict the Balmer series, in 1885. Balmer lines are historically referred to as "H-alpha", "H-beta", "H-gamma" and so on, where H is the element hydrogen.[8] Four of the Balmer lines are in the technically "visible" part of the spectrum, with wavelengths longer than 400 nm and shorter than 700 nm. Parts of the Balmer series can be seen in the solar spectrum. H-alpha is an important line used in astronomy to detect the presence of hydrogen.

| n | λ, air

(nm) |

|---|---|

| 3 | 656.3 |

| 4 | 486.1 |

| 5 | 434.0 |

| 6 | 410.2 |

| 7 | 397.0 |

| ∞ | 364.6 |

Paschen series (Bohr series n' = 3)

Named after the German physicist Friedrich Paschen who first observed them in 1908. The Paschen lines all lie in the infrared band.[9] This series overlaps with the next (Brackett) series, i.e. the shortest line in the Brackett series has a wavelength that falls among the Paschen series. All subsequent series overlap.

| n | λ, air

(nm) |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1875 |

| 5 | 1282 |

| 6 | 1094 |

| 7 | 1005 |

| 8 | 954.6 |

| 9 | 922.9 |

| ∞ | 820.4 |

Brackett series (n′ = 4)

Named after the American physicist Frederick Sumner Brackett who first observed the spectral lines in 1922.[10]

| n | λ, air

(nm) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 4051 |

| 6 | 2625 |

| 7 | 2166 |

| 8 | 1944 |

| 9 | 1817 |

| ∞ | 1458 |

Pfund series (n′ = 5)

Experimentally discovered in 1924 by August Herman Pfund.[11]

| n | λ, vacuum

(nm) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 7460 |

| 7 | 4654 |

| 8 | 3741 |

| 9 | 3297 |

| 10 | 3039 |

| ∞ | 2279 |

Humphreys series (n′ = 6)

Discovered in 1953 by American physicist Curtis J. Humphreys.[13]

| n | λ, vacuum

(μm) |

|---|---|

| 7 | 12.37 |

| 8 | 7.503 |

| 9 | 5.908 |

| 10 | 5.129 |

| 11 | 4.673 |

| ∞ | 3.282 |

Further(n′ > 6)

Further series are unnamed, but follow exactly the same pattern as dictated by the Rydberg equation. Series are increasingly spread out and occur in increasing wavelengths. The lines are also increasingly faint, corresponding to increasingly rare atomic events.

Extension to other systems

The concepts of the Rydberg formula can be applied to any system with a single particle orbiting a nucleus, for example a He+ ion or a muonium exotic atom. The equation must be modified based on the system's Bohr radius; emissions will be of a similar character but at a different range of energies.

All other atoms possess at least two electrons in their neutral form and the interactions between these electrons makes analysis of the spectrum by such simple methods as described here impractical. The deduction of the Rydberg formula was a major step in physics, but it was long before an extension to the spectra of other elements could be accomplished.

See also

- The hydrogen line (21 cm)

- Astronomical spectroscopy

- Moseley's law

- Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation

References

- ↑ "The Hydrogen 21-cm Line". Hyperphysics. Georgia State University. 2004-10-30. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ↑ Liboff, Richard L. (2002). Introductory Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-8053-8714-5.

- ↑ Bohr, Niels (1985), "Rydberg's discovery of the spectral laws", in Kalckar, J., N. Bohr: Collected Works 10, Amsterdam: North-Holland Publ., pp. 373–9

- ↑ "CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006" (PDF). Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA). NIST.

- ↑ Lyman, Theodore (1906), "The Spectrum of Hydrogen in the Region of Extremely Short Wave-Length", Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, New Series 13 (3): 125–146, ISSN 0096-6134, JSTOR 25058084

- ↑ Lyman, Theodore (1914), "An Extension of the Spectrum in the Extreme Ultra-Violet", Nature 93: 241, Bibcode:1914Natur..93..241L, doi:10.1038/093241a0

- 1 2 3 4 Wiese, W. L.; Fuhr, J. R. (2009). "Accurate Atomic Transition Probabilities for Hydrogen, Helium, and Lithium". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 38 (3): 565. Bibcode:2009JPCRD..38..565W. doi:10.1063/1.3077727.

- ↑ Balmer, J. J. (1885), "Notiz uber die Spectrallinien des Wasserstoffs", Annalen der Physik 261 (5): 80–87, Bibcode:1885AnP...261...80B, doi:10.1002/andp.18852610506

- ↑ Paschen, Friedrich (1908), "Zur Kenntnis ultraroter Linienspektra. I. (Normalwellenlängen bis 27000 Å.-E.)", Annalen der Physik 332 (13): 537–570, Bibcode:1908AnP...332..537P, doi:10.1002/andp.19083321303

- ↑ Brackett, Frederick Sumner (1922), "Visible and Infra-Red Radiation of Hydrogen", Astrophysical Journal 56: 154, Bibcode:1922ApJ....56..154B, doi:10.1086/142697

- ↑ Pfund, A. H. (1924), "The emission of nitrogen and hydrogen in infrared", J. Opt. Soc. Am. 9 (3): 193–196, doi:10.1364/JOSA.9.000193

- 1 2 Kramida, A.E. (November 2010). "A critical compilation of experimental data on spectral lines and energy levels of hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium". Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 96 (6): 586–644. Bibcode:2010ADNDT..96..586K. doi:10.1016/j.adt.2010.05.001.

- ↑ Humphreys, C.J. (1953), "The Sixth Series in the Spectrum of Atomic Hydrogen", J. Research Natl. Bur. Standards 50