Hydrogen bond

A hydrogen bond is the electrostatic attraction between polar groups that occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom bound to a highly electronegative atom such as nitrogen (N), oxygen (O) or fluorine (F) experiences attraction to some other nearby highly electronegative atom.

These hydrogen-bond attractions can occur between molecules (intermolecular) or within different parts of a single molecule (intramolecular).[2] Depending on geometry and environmental conditions, the hydrogen bond may be worth between 5 and 30 kJ/mole in thermodynamic terms. This makes it stronger than a van der Waals interaction, but weaker than covalent or ionic bonds. This type of bond can occur in inorganic molecules such as water and in organic molecules like DNA and proteins.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonding is responsible for the high boiling point of water (100 °C) compared to the other group 16 hydrides that have no hydrogen bonds. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding is partly responsible for the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins and nucleic acids. It also plays an important role in the structure of polymers, both synthetic and natural.

In 2011, an IUPAC Task Group recommended a modern evidence-based definition of hydrogen bonding, which was published in the IUPAC journal Pure and Applied Chemistry. This definition specifies that The hydrogen bond is an attractive interaction between a hydrogen atom from a molecule or a molecular fragment X–H in which X is more electronegative than H, and an atom or a group of atoms in the same or a different molecule, in which there is evidence of bond formation.[3] An accompanying detailed technical report provides the rationale behind the new definition.[4]

Bonding

A hydrogen atom attached to a relatively electronegative atom will play the role of the hydrogen bond donor.[6] This electronegative atom is usually fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen. A hydrogen attached to carbon can also participate in hydrogen bonding when the carbon atom is bound to electronegative atoms, as is the case in chloroform, CHCl3.[7][8][9] An example of a hydrogen bond donor is the hydrogen from the hydroxyl group of ethanol, which is bonded to an oxygen.

An electronegative atom such as fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen will be the hydrogen bond acceptor, whether or not it is bonded to a hydrogen atom. An example of a hydrogen bond acceptor that does not have a hydrogen atom bonded to it is the oxygen atom in diethyl ether.

In the donor molecule, the electronegative atom attracts the electron cloud from around the hydrogen nucleus of the donor, and, by decentralizing the cloud, leaves the atom with a positive partial charge. Because of the small size of hydrogen relative to other atoms and molecules, the resulting charge, though only partial, represents a large charge density. A hydrogen bond results when this strong positive charge density attracts a lone pair of electrons on another heteroatom, which then becomes the hydrogen-bond acceptor.

The hydrogen bond is often described as an electrostatic dipole-dipole interaction. However, it also has some features of covalent bonding: it is directional and strong, produces interatomic distances shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii, and usually involves a limited number of interaction partners, which can be interpreted as a type of valence. These covalent features are more substantial when acceptors bind hydrogens from more electronegative donors.

The partially covalent nature of a hydrogen bond raises the following questions: "To which molecule or atom does the hydrogen nucleus belong?" and "Which should be labeled 'donor' and which 'acceptor'?" Usually, this is simple to determine on the basis of interatomic distances in the X−H…Y system, where the dots represent the hydrogen bond: the X−H distance is typically ≈110 pm, whereas the H…Y distance is ≈160 to 200 pm. Liquids that display hydrogen bonding (such as water) are called associated liquids.

Hydrogen bonds can vary in strength from very weak (1–2 kJ mol−1) to extremely strong (161.5 kJ mol−1 in the ion HF−

2).[10][11] Typical enthalpies in vapor include:

- F−H…:F (161.5 kJ/mol or 38.6 kcal/mol)

- O−H…:N (29 kJ/mol or 6.9 kcal/mol)

- O−H…:O (21 kJ/mol or 5.0 kcal/mol)

- N−H…:N (13 kJ/mol or 3.1 kcal/mol)

- N−H…:O (8 kJ/mol or 1.9 kcal/mol)

- HO−H…:OH+

3 (18 kJ/mol[12] or 4.3 kcal/mol; data obtained using molecular dynamics as detailed in the reference and should be compared to 7.9 kJ/mol for bulk water, obtained using the same molecular dynamics.)

Quantum chemical calculations of the relevant interresidue potential constants (compliance constants) revealed large differences between individual H bonds of the same type. For example, the central interresidue N−H···N hydrogen bond between guanine and cytosine is much stronger in comparison to the N−H···N bond between the adenine-thymine pair.[13]

The length of hydrogen bonds depends on bond strength, temperature, and pressure. The bond strength itself is dependent on temperature, pressure, bond angle, and environment (usually characterized by local dielectric constant). The typical length of a hydrogen bond in water is 197 pm. The ideal bond angle depends on the nature of the hydrogen bond donor. The following hydrogen bond angles between a hydrofluoric acid donor and various acceptors have been determined experimentally:[14]

| Acceptor…donor | VSEPR symmetry | Angle (°) |

| HCN…HF | linear | 180 |

| H2CO…HF | trigonal planar | 120 |

| H2O…HF | pyramidal | 46 |

| H2S…HF | pyramidal | 89 |

| SO2…HF | trigonal | 142 |

History

In the book The Nature of the Chemical Bond, Linus Pauling credits T. S. Moore and T. F. Winmill with the first mention of the hydrogen bond, in 1912.[15][16] Moore and Winmill used the hydrogen bond to account for the fact that trimethylammonium hydroxide is a weaker base than tetramethylammonium hydroxide. The description of hydrogen bonding in its better-known setting, water, came some years later, in 1920, from Latimer and Rodebush.[17] In that paper, Latimer and Rodebush cite work by a fellow scientist at their laboratory, Maurice Loyal Huggins, saying, "Mr. Huggins of this laboratory in some work as yet unpublished, has used the idea of a hydrogen kernel held between two atoms as a theory in regard to certain organic compounds."

Hydrogen bonds in water

The most ubiquitous and perhaps simplest example of a hydrogen bond is found between water molecules. In a discrete water molecule, there are two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Two molecules of water can form a hydrogen bond between them; the simplest case, when only two molecules are present, is called the water dimer and is often used as a model system. When more molecules are present, as is the case with liquid water, more bonds are possible because the oxygen of one water molecule has two lone pairs of electrons, each of which can form a hydrogen bond with a hydrogen on another water molecule. This can repeat such that every water molecule is H-bonded with up to four other molecules, as shown in the figure (two through its two lone pairs, and two through its two hydrogen atoms). Hydrogen bonding strongly affects the crystal structure of ice, helping to create an open hexagonal lattice. The density of ice is less than the density of water at the same temperature; thus, the solid phase of water floats on the liquid, unlike most other substances.

Liquid water's high boiling point is due to the high number of hydrogen bonds each molecule can form, relative to its low molecular mass. Owing to the difficulty of breaking these bonds, water has a very high boiling point, melting point, and viscosity compared to otherwise similar liquids not conjoined by hydrogen bonds. Water is unique because its oxygen atom has two lone pairs and two hydrogen atoms, meaning that the total number of bonds of a water molecule is up to four. For example, hydrogen fluoride—which has three lone pairs on the F atom but only one H atom—can form only two bonds; (ammonia has the opposite problem: three hydrogen atoms but only one lone pair).

- H−F…H−F…H−F

The exact number of hydrogen bonds formed by a molecule of liquid water fluctuates with time and depends on the temperature.[18] From TIP4P liquid water simulations at 25 °C, it was estimated that each water molecule participates in an average of 3.59 hydrogen bonds. At 100 °C, this number decreases to 3.24 due to the increased molecular motion and decreased density, while at 0 °C, the average number of hydrogen bonds increases to 3.69.[18] A more recent study found a much smaller number of hydrogen bonds: 2.357 at 25 °C.[19] The differences may be due to the use of a different method for defining and counting the hydrogen bonds.

Where the bond strengths are more equivalent, one might instead find the atoms of two interacting water molecules partitioned into two polyatomic ions of opposite charge, specifically hydroxide (OH−) and hydronium (H3O+). (Hydronium ions are also known as "hydroxonium" ions.)

- H−O− H3O+

Indeed, in pure water under conditions of standard temperature and pressure, this latter formulation is applicable only rarely; on average about one in every 5.5 × 108 molecules gives up a proton to another water molecule, in accordance with the value of the dissociation constant for water under such conditions. It is a crucial part of the uniqueness of water.

Because water may form hydrogen bonds with solute proton donors and acceptors, it may competitively inhibit the formation of solute intermolecular or intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Consequently, hydrogen bonds between or within solute molecules dissolved in water are almost always unfavorable relative to hydrogen bonds between water and the donors and acceptors for hydrogen bonds on those solutes.[20] Hydrogen bonds between water molecules have a duration of about 10−10 seconds.[21]

Bifurcated and over-coordinated hydrogen bonds in water

A single hydrogen atom can participate in two hydrogen bonds, rather than one. This type of bonding is called "bifurcated" (split in two or "two-forked"). It can exist for instance in complex natural or synthetic organic molecules.[22] It has been suggested that a bifurcated hydrogen atom is an essential step in water reorientation.[23]

Acceptor-type hydrogen bonds (terminating on an oxygen's lone pairs) are more likely to form bifurcation (it is called overcoordinated oxygen, OCO) than are donor-type hydrogen bonds, beginning on the same oxygen's hydrogens.[24]

Hydrogen bonds in DNA and proteins

Hydrogen bonding also plays an important role in determining the three-dimensional structures adopted by proteins and nucleic bases. In these macromolecules, bonding between parts of the same macromolecule cause it to fold into a specific shape, which helps determine the molecule's physiological or biochemical role. For example, the double helical structure of DNA is due largely to hydrogen bonding between its base pairs (as well as pi stacking interactions), which link one complementary strand to the other and enable replication.

In the secondary structure of proteins, hydrogen bonds form between the backbone oxygens and amide hydrogens. When the spacing of the amino acid residues participating in a hydrogen bond occurs regularly between positions i and i + 4, an alpha helix is formed. When the spacing is less, between positions i and i + 3, then a 310 helix is formed. When two strands are joined by hydrogen bonds involving alternating residues on each participating strand, a beta sheet is formed. Hydrogen bonds also play a part in forming the tertiary structure of protein through interaction of R-groups. (See also protein folding).

The role of hydrogen bonds in protein folding has also been linked to osmolyte-induced protein stabilization. Protective osmolytes, such as trehalose and sorbitol, shift the protein folding equilibrium toward the folded state, in a concentration dependent manner. While the prevalent explanation for osmolyte action relies on excluded volume effects, that are entropic in nature, recent Circular dichroism (CD) experiments have shown osmolyte to act through an enthalpic effect.[25] The molecular mechanism for their role in protein stabilization is still not well established, though several mechanism have been proposed. Recently, computer molecular dynamics simulations suggested that osmolytes stabilize proteins by modifying the hydrogen bonds in the protein hydration layer.[26]

Several studies have shown that hydrogen bonds play an important role for the stability between subunits in multimeric proteins. For example, a study of sorbitol dehydrogenase displayed an important hydrogen bonding network which stabilizes the tetrameric quaternary structure within the mammalian sorbitol dehydrogenase protein family.[27]

A protein backbone hydrogen bond incompletely shielded from water attack is a dehydron. Dehydrons promote the removal of water through proteins or ligand binding. The exogenous dehydration enhances the electrostatic interaction between the amide and carbonyl groups by de-shielding their partial charges. Furthermore, the dehydration stabilizes the hydrogen bond by destabilizing the nonbonded state consisting of dehydrated isolated charges.[28]

Hydrogen bonds in polymers

Many polymers are strengthened by hydrogen bonds in their main chains. Among the synthetic polymers, the best known example is nylon, where hydrogen bonds occur in the repeat unit and play a major role in crystallization of the material. The bonds occur between carbonyl and amine groups in the amide repeat unit. They effectively link adjacent chains to create crystals, which help reinforce the material. The effect is greatest in aramid fibre, where hydrogen bonds stabilize the linear chains laterally. The chain axes are aligned along the fibre axis, making the fibres extremely stiff and strong. Hydrogen bonds are also important in the structure of cellulose and derived polymers in its many different forms in nature, such as wood and natural fibres such as cotton and flax.

The hydrogen bond networks make both natural and synthetic polymers sensitive to humidity levels in the atmosphere because water molecules can diffuse into the surface and disrupt the network. Some polymers are more sensitive than others. Thus nylons are more sensitive than aramids, and nylon 6 more sensitive than nylon-11.

Symmetric hydrogen bond

A symmetric hydrogen bond is a special type of hydrogen bond in which the proton is spaced exactly halfway between two identical atoms. The strength of the bond to each of those atoms is equal. It is an example of a three-center four-electron bond. This type of bond is much stronger than a "normal" hydrogen bond. The effective bond order is 0.5, so its strength is comparable to a covalent bond. It is seen in ice at high pressure, and also in the solid phase of many anhydrous acids such as hydrofluoric acid and formic acid at high pressure. It is also seen in the bifluoride ion [F−H−F]−.

Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been observed recently spectroscopically in formic acid at high pressure (>GPa). Each hydrogen atom forms a partial covalent bond with two atoms rather than one. Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been postulated in ice at high pressure (Ice X). Low-barrier hydrogen bonds form when the distance between two heteroatoms is very small.

Dihydrogen bond

The hydrogen bond can be compared with the closely related dihydrogen bond, which is also an intermolecular bonding interaction involving hydrogen atoms. These structures have been known for some time, and well characterized by crystallography;[29] however, an understanding of their relationship to the conventional hydrogen bond, ionic bond, and covalent bond remains unclear. Generally, the hydrogen bond is characterized by a proton acceptor that is a lone pair of electrons in nonmetallic atoms (most notably in the nitrogen, and chalcogen groups). In some cases, these proton acceptors may be pi-bonds or metal complexes. In the dihydrogen bond, however, a metal hydride serves as a proton acceptor, thus forming a hydrogen-hydrogen interaction. Neutron diffraction has shown that the molecular geometry of these complexes is similar to hydrogen bonds, in that the bond length is very adaptable to the metal complex/hydrogen donor system.[29]

Advanced theory of the hydrogen bond

In 1999, Isaacs et al.[30] showed from interpretations of the anisotropies in the Compton profile of ordinary ice that the hydrogen bond is partly covalent. Some NMR data on hydrogen bonds in proteins also indicate covalent bonding.

Most generally, the hydrogen bond can be viewed as a metric-dependent electrostatic scalar field between two or more intermolecular bonds. This is slightly different from the intramolecular bound states of, for example, covalent or ionic bonds; however, hydrogen bonding is generally still a bound state phenomenon, since the interaction energy has a net negative sum. The initial theory of hydrogen bonding proposed by Linus Pauling suggested that the hydrogen bonds had a partial covalent nature. This remained a controversial conclusion until the late 1990s when NMR techniques were employed by F. Cordier et al. to transfer information between hydrogen-bonded nuclei, a feat that would only be possible if the hydrogen bond contained some covalent character.[31] While much experimental data has been recovered for hydrogen bonds in water, for example, that provide good resolution on the scale of intermolecular distances and molecular thermodynamics, the kinetic and dynamical properties of the hydrogen bond in dynamic systems remain unchanged.

Dynamics probed by spectroscopic means

The dynamics of hydrogen bond structures in water can be probed by the IR spectrum of OH stretching vibration.[32] In terms of hydrogen bonding network in protic organic ionic plastic crystals (POIPCs), which are a type of phase change materials exhibiting solid-solid phase transitions prior to melting, variable-temperature infrared spectroscopy can reveal the temperature dependence of hydrogen bonds and the dynamics of both the anions and the cations.[33] The sudden weakening of hydrogen bonds during the solid-solid phase transition seems to be coupled with the onset of orientational or rotational disorder of the ions.[33]

Hydrogen bonding phenomena

- Dramatically higher boiling points of NH3, H2O, and HF compared to the heavier analogues PH3, H2S, and HCl.

- Increase in the melting point, boiling point, solubility, and viscosity of many compounds can be explained by the concept of hydrogen bonding.

- Occurrence of proton tunneling during DNA replication is believed to be responsible for cell mutations.[34]

- Viscosity of anhydrous phosphoric acid and of glycerol

- Dimer formation in carboxylic acids and hexamer formation in hydrogen fluoride, which occur even in the gas phase, resulting in gross deviations from the ideal gas law.

- Pentamer formation of water and alcohols in apolar solvents.

- High water solubility of many compounds such as ammonia is explained by hydrogen bonding with water molecules.

- Negative azeotropy of mixtures of HF and water

- Deliquescence of NaOH is caused in part by reaction of OH− with moisture to form hydrogen-bonded H

3O−

2 species. An analogous process happens between NaNH2 and NH3, and between NaF and HF. - The fact that ice is less dense than liquid water is due to a crystal structure stabilized by hydrogen bonds.

- The presence of hydrogen bonds can cause an anomaly in the normal succession of states of matter for certain mixtures of chemical compounds as temperature increases or decreases. These compounds can be liquid until a certain temperature, then solid even as the temperature increases, and finally liquid again as the temperature rises over the "anomaly interval"[35]

- Smart rubber utilizes hydrogen bonding as its sole means of bonding, so that it can "heal" when torn, because hydrogen bonding can occur on the fly between two surfaces of the same polymer.

- Strength of nylon and cellulose fibres.

- Wool, being a protein fibre, is held together by hydrogen bonds, causing wool to recoil when stretched. However, washing at high temperatures can permanently break the hydrogen bonds and a garment may permanently lose its shape.

References

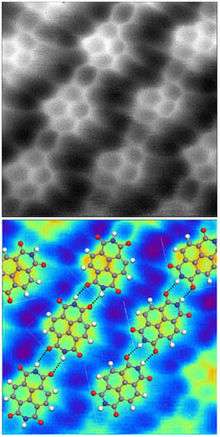

- ↑ Sweetman, A. M.; Jarvis, S. P.; Sang, Hongqian; Lekkas, I.; Rahe, P.; Wang, Yu; Wang, Jianbo; Champness, N.R.; Kantorovich, L.; Moriarty, P. (2014). "Mapping the force field of a hydrogen-bonded assembly". Nature Communications 5. doi:10.1038/ncomms4931.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "hydrogen bond".

- ↑ Arunan, Elangannan; Desiraju, Gautam R.; Klein, Roger A.; Sadlej, Joanna; Scheiner, Steve; Alkorta, Ibon; Clary, David C.; Crabtree, Robert H.; Dannenberg, Joseph J.; Hobza, Pavel; Kjaergaard, Henrik G.; Legon, Anthony C.; Mennucci, Benedetta; Nesbitt, David J. (2011). "Definition of the hydrogen bond". Pure Appl. Chem. 83 (8): 1637–1641. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-01-02.

- ↑ Arunan, Elangannan; Desiraju, Gautam R.; Klein, Roger A.; Sadlej, Joanna; Scheiner, Steve; Alkorta, Ibon; Clary, David C.; Crabtree, Robert H.; Dannenberg, Joseph J.; Hobza, Pavel; Kjaergaard, Henrik G.; Legon, Anthony C.; Mennucci, Benedetta; Nesbitt, David J. (2011). "Defining the hydrogen bond: An Account". Pure Appl. Chem. 83 (8): 1619–1636. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-10-01-01.

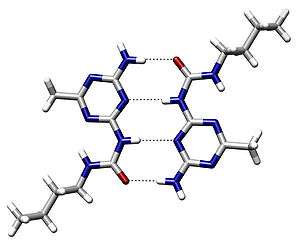

- ↑ Beijer, Felix H.; Kooijman, Huub; Spek, Anthony L.; Sijbesma, Rint P.; Meijer, E. W. (1998). "Self-Complementarity Achieved through Quadruple Hydrogen Bonding". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37 (1–2): 75–78. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980202)37:1/2<75::AID-ANIE75>3.0.CO;2-R.

- ↑ Campbell, Neil A.; Brad Williamson; Robin J. Heyden (2006). Biology: Exploring Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-250882-6.

- ↑ Wiley, G.R. and Miller, S.I. (1972). "Thermodynamic parameters for hydrogen bonding of chloroform with Lewis bases in cyclohexane. Proton magnetic resonance study". Journal of the American Chemical Society 94 (10): 3287. doi:10.1021/ja00765a001.

- ↑ Kwak, K; Rosenfeld, DE; Chung, JK; Fayer, MD (2008). "Solute-solvent complex switching dynamics of chloroform between acetone and dimethylsulfoxide-two-dimensional IR chemical exchange spectroscopy". The journal of physical chemistry. B 112 (44): 13906–15. doi:10.1021/jp806035w. PMC 2646412. PMID 18855462.

- ↑ Romańczyk, P. P.; Radoń, M.; Noga, K.; Kurek, S. S. (2013). "Autocatalytic cathodic dehalogenation triggered by dissociative electron transfer through a C-H...O hydrogen bond". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15: 17522–17536. doi:10.1039/C3CP52933A.

- ↑ Larson, J. W.; McMahon, T. B. (1984). "Gas-phase bihalide and pseudobihalide ions. An ion cyclotron resonance determination of hydrogen bond energies in XHY- species (X, Y = F, Cl, Br, CN)". Inorganic Chemistry 23 (14): 2029–2033. doi:10.1021/ic00182a010.

- ↑ Emsley, J. (1980). "Very Strong Hydrogen Bonds". Chemical Society Reviews 9 (1): 91–124. doi:10.1039/cs9800900091.

- ↑ Markovitch, Omer and Agmon, Noam (2007). "Structure and energetics of the hydronium hydration shells". J. Phys. Chem. A 111 (12): 2253–2256. doi:10.1021/jp068960g. PMID 17388314.

- ↑ Grunenberg, Jörg (2004). "Direct Assessment of Interresidue Forces in Watson−Crick Base Pairs Using Theoretical Compliance Constants". Journal of the American Chemical Society 126 (50): 16310–1. doi:10.1021/ja046282a. PMID 15600318.

- ↑ Legon, A. C.; Millen, D. J. (1987). "Angular geometries and other properties of hydrogen-bonded dimers: a simple electrostatic interpretation of the success of the electron-pair model". Chemical Society Reviews 16: 467. doi:10.1039/CS9871600467.

- ↑ Pauling, L. (1960). The nature of the chemical bond and the structure of molecules and crystals; an introduction to modern structural chemistry (3rd ed.). Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press. p. 450. ISBN 0-8014-0333-2.

- ↑ Moore, T. S. and Winmill, T. F. (1912). "The state of amines in aqueous solution". J. Chem. Soc. 101: 1635. doi:10.1039/CT9120101635.

- ↑ Latimer, Wendell M.; Rodebush, Worth H. (1920). "Polarity and ionization from the standpoint of the Lewis theory of valence.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 42 (7): 1419–1433. doi:10.1021/ja01452a015.

- 1 2 Jorgensen, W. L. and Madura, J. D. (1985). "Temperature and size dependence for Monte Carlo simulations of TIP4P water". Mol. Phys. 56 (6): 1381. Bibcode:1985MolPh..56.1381J. doi:10.1080/00268978500103111.

- ↑ Zielkiewicz, Jan (2005). "Structural properties of water: Comparison of the SPC, SPCE, TIP4P, and TIP5P models of water". J. Chem. Phys. 123 (10): 104501. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123j4501Z. doi:10.1063/1.2018637. PMID 16178604.

- ↑ Jencks, William; Jencks, William P. (1986). "Hydrogen Bonding between Solutes in Aqueous Solution". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 108 (14): 4196. doi:10.1021/ja00274a058.

- ↑ Dillon, P. F. (2012). Biophysics. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-139-50462-1.

- ↑ Baron, Michel; Giorgi-Renault, Sylviane; Renault, Jean; Mailliet, Patrick; Carré, Daniel; Etienne, Jean (1984). "Hétérocycles à fonction quinone. V. Réaction anormale de la butanedione avec la diamino-1,2 anthraquinone; structure cristalline de la naphto \2,3-f] quinoxalinedione-7,12 obtenue". Can. J. Chem. 62 (3): 526–530. doi:10.1139/v84-087.

- ↑ Laage, Damien and Hynes, James T. (2006). "A Molecular Jump Mechanism for Water Reorientation". Science 311 (5762): 832–5. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..832L. doi:10.1126/science.1122154. PMID 16439623.

- ↑ Markovitch, Omer and Agmon, Noam (2008). "The Distribution of Acceptor and Donor Hydrogen-Bonds in Bulk Liquid Water". Molecular Physics 106 (2): 485. Bibcode:2008MolPh.106..485M. doi:10.1080/00268970701877921.

- ↑ Politi, Regina; Harries, Daniel (2010). "Enthalpically driven peptide stabilization by protective osmolytes". ChemComm 46 (35): 6449–6451. doi:10.1039/C0CC01763A.

- ↑ Gilman-Politi, Regina; Harries, Daniel (2011). "Unraveling the Molecular Mechanism of Enthalpy Driven Peptide Folding by Polyol Osmolytes". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 7 (11): 3816–3828. doi:10.1021/ct200455n.

- ↑ Hellgren, M; Kaiser, C; de Haij, S; Norberg, A; Höög, JO (December 2007). "A hydrogen-bonding network in mammalian sorbitol dehydrogenase stabilizes the tetrameric state and is essential for the catalytic power.". Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 64 (23): 3129–38. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7318-1. PMID 17952367.

- ↑ Fernández, A; Rogale K; Scott Ridgway; Scheraga H.A. (June 2004). "Inhibitor design by wrapping packing defects in HIV-1 proteins.". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 (32): 11640–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404641101. PMID 15289598.

- 1 2 Crabtree, Robert H.; Siegbahn, Per E. M.; Eisenstein, Odile; Rheingold, Arnold L.; Koetzle, Thomas F. (1996). "A New Intermolecular Interaction: Unconventional Hydrogen Bonds with Element-Hydride Bonds as Proton Acceptor". Acc. Chem. Res. 29 (7): 348–354. doi:10.1021/ar950150s. PMID 19904922.

- ↑ Isaacs, E.D.; et al. (1999). "Covalency of the Hydrogen Bond in Ice: A Direct X-Ray Measurement". Physical Review Letters 82 (3): 600–603. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82..600I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.600.

- ↑ Cordier, F; Rogowski, M; Grzesiek, S; Bax, A (1999). "Observation of through-hydrogen-bond (2h)J(HC') in a perdeuterated protein". J Magn Reson. 140 (2): 510–2. Bibcode:1999JMagR.140..510C. doi:10.1006/jmre.1999.1899. PMID 10497060.

- ↑ Cowan ML; Bruner BD; Huse N; et al. (2005). "Ultrafast memory loss and energy redistribution in the hydrogen bond network of liquid H2O". Nature 434 (7030): 199–202. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..199C. doi:10.1038/nature03383. PMID 15758995.

- 1 2 Luo, Jiangshui; Jensen, Annemette H.; Brooks, Neil R.; Sniekers, Jeroen; Knipper, Martin; Aili, David; Li, Qingfeng; Vanroy, Bram; Wübbenhorst, Michael; Yan, Feng; Van Meervelt, Luc; Shao, Zhigang; Fang, Jianhua; Luo, Zheng-Hong; De Vos, Dirk E.; Binnemans, Koen; Fransaer, Jan (2015). "1,2,4-Triazolium perfluorobutanesulfonate as an archetypal pure protic organic ionic plastic crystal electrolyte for all-solid-state fuel cells". Energy & Environmental Science 8 (4): 1276. doi:10.1039/C4EE02280G.

- ↑ Löwdin, P. O. (1963). "Proton Tunneling in DNA and its Biological Implications". Rev. Mod. Phys. 35: 724. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.35.724.

- ↑ Law-breaking liquid defies the rules. Physicsworld.com (September 24, 2004 )

Further reading

- George A. Jeffrey. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding (Topics in Physical Chemistry). Oxford University Press, USA (March 13, 1997). ISBN 0-19-509549-9

External links

- The Bubble Wall (Audio slideshow from the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory explaining cohesion, surface tension and hydrogen bonds)

- isotopic effect on bond dynamics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|