Hydraulic machinery

Hydraulic machines are machinery and tools that use liquid fluid power to do simple work. Heavy equipment is a common example.

In this type of machine, hydraulic fluid is transmitted throughout the machine to various hydraulic motors and hydraulic cylinders and becomes pressurised according to the resistance present. The fluid is controlled directly or automatically by control valves and distributed through hoses and tubes.

The popularity of hydraulic machinery is due to the very large amount of power that can be transferred through small tubes and flexible hoses, and the high power density and wide array of actuators that can make use of this power.

Hydraulic machinery is operated by the use of hydraulics, where a liquid is the powering medium.

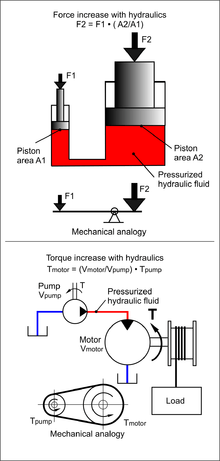

Force and torque multiplication

A fundamental feature of hydraulic systems is the ability to apply force or torque multiplication in an easy way, independent of the distance between the input and output, without the need for mechanical gears or levers, either by altering the effective areas in two connected cylinders or the effective displacement (cc/rev) between a pump and motor. In normal cases, hydraulic ratios are combined with a mechanical force or torque ratio for optimum machine designs such as boom movements and trackdrives for an excavator.

- Examples

- Two hydraulic cylinders interconnected

Cylinder C1 is one inch in radius, and cylinder C2 is ten inches in radius. If the force exerted on C1 is 10 lbf, the force exerted by C2 is 1000 lbf because C2 is a hundred times larger in area (S = πr²) as C1. The downside to this is that you have to move C1 a hundred inches to move C2 one inch. The most common use for this is the classical hydraulic jack where a pumping cylinder with a small diameter is connected to the lifting cylinder with a large diameter.

- Pump and motor

If a hydraulic rotary pump with the displacement 10 cc/rev is connected to a hydraulic rotary motor with 100 cc/rev, the shaft torque required to drive the pump is 10 times less than the torque available at the motor shaft, but the shaft speed (rev/min) for the motor is 10 times less than the pump shaft speed. This combination is actually the same type of force multiplication as the cylinder example (1) just that the linear force in this case is a rotary force, defined as torque.

Both these examples are usually referred to as a hydraulic transmission or hydrostatic transmission involving a certain hydraulic "gear ratio".

Hydraulic circuits

For the hydraulic fluid to do work, it must flow to the actuator and/or motors, then return to a reservoir. The fluid is then filtered and re-pumped. The path taken by hydraulic fluid is called a hydraulic circuit of which there are several types. Open center circuits use pumps which supply a continuous flow. The flow is returned to tank through the control valve's open center; that is, when the control valve is centered, it provides an open return path to tank and the fluid is not pumped to a high pressure. Otherwise, if the control valve is actuated it routes fluid to and from an actuator and tank. The fluid's pressure will rise to meet any resistance, since the pump has a constant output. If the pressure rises too high, fluid returns to tank through a pressure relief valve. Multiple control valves may be stacked in series . This type of circuit can use inexpensive, constant displacement pumps.

Closed center circuits supply full pressure to the control valves, whether any valves are actuated or not. The pumps vary their flow rate, pumping very little hydraulic fluid until the operator actuates a valve. The valve's spool therefore doesn't need an open center return path to tank. Multiple valves can be connected in a parallel arrangement and system pressure is equal for all valves.

Constant pressure and load-sensing systems

The closed center circuits exist in two basic configurations, normally related to the regulator for the variable pump that supplies the oil:

Constant pressure systems (CP-system), standard. Pump pressure always equals the pressure setting for the pump regulator. This setting must cover the maximum required load pressure. Pump delivers flow according to required sum of flow to the consumers. The CP-system generates large power losses if the machine works with large variations in load pressure and the average system pressure is much lower than the pressure setting for the pump regulator. CP is simple in design. Works like a pneumatic system. New hydraulic functions can easily be added and the system is quick in response.

Constant pressure systems (CP-system), unloaded. Same basic configuration as 'standard' CP-system but the pump is unloaded to a low stand-by pressure when all valves are in neutral position. Not so fast response as standard CP but pump lifetime is prolonged.

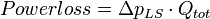

Load-sensing systems (LS-system) generates less power losses as the pump can reduce both flow and pressure to match the load requirements, but requires more tuning than the CP-system with respect to system stability. The LS-system also requires additional logical valves and compensator valves in the directional valves, thus it is technically more complex and more expensive than the CP-system. The LS-system system generates a constant power loss related to the regulating pressure drop for the pump regulator:

The average  is around 2 MPa (290 psi). If the pump flow is high the extra loss can be considerable. The power loss also increases if the load pressures vary a lot. The cylinder areas, motor displacements and mechanical torque arms must be designed to match load pressure in order to bring down the power losses. Pump pressure always equals the maximum load pressure when several functions are run simultaneously and the power input to the pump equals the (max. load pressure + ΔpLS) x sum of flow.

is around 2 MPa (290 psi). If the pump flow is high the extra loss can be considerable. The power loss also increases if the load pressures vary a lot. The cylinder areas, motor displacements and mechanical torque arms must be designed to match load pressure in order to bring down the power losses. Pump pressure always equals the maximum load pressure when several functions are run simultaneously and the power input to the pump equals the (max. load pressure + ΔpLS) x sum of flow.

Five basic types of load-sensing systems

- Load sensing without compensators in the directional valves. Hydraulically controlled LS-pump.

- Load sensing with up-stream compensator for each connected directional valve. Hydraulically controlled LS-pump.

- Load sensing with down-stream compensator for each connected directional valve. Hydraulically controlled LS-pump.

- Load sensing with a combination of up-stream and down-stream compensators. Hydraulically controlled LS-pump.

- Load sensing with synchronized, both electric controlled pump displacement and electric controlled valve flow area for faster response, increased stability and fewer system losses. This is a new type of LS-system, not yet fully developed.

Technically the down-stream mounted compensator in a valveblock can physically be mounted "up-stream", but work as a down-stream compensator.

System type (3) gives the advantage that activated functions are synchronized independent of pump flow capacity. The flow relation between 2 or more activated functions remains independent of load pressures, even if the pump reaches the maximum swivel angle. This feature is important for machines that often run with the pump at maximum swivel angle and with several activated functions that must be synchronized in speed, such as with excavators. With type (4) system, the functions with up-stream compensators have priority. Example: Steering-function for a wheel loader. The system type with down-stream compensators usually have a unique trademark depending on the manufacturer of the valves, for example "LSC" (Linde Hydraulics), "LUDV" (Bosch Rexroth Hydraulics) and "Flowsharing" (Parker Hydraulics) etc. No official standardized name for this type of system has been established but Flowsharing is a common name for it.

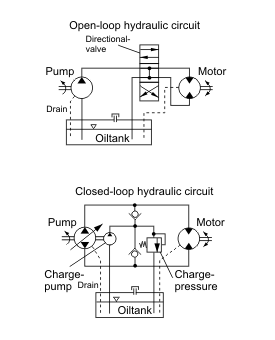

Open and closed circuits

Open-loop: Pump-inlet and motor-return (via the directional valve) are connected to the hydraulic tank. The term loop applies to feedback; the more correct term is open versus closed "circuit". Open center circuits use pumps which supply a continuous flow. The flow is returned to tank through the control valve's open center; that is, when the control valve is centered, it provides an open return path to tank and the fluid is not pumped to a high pressure. Otherwise, if the control valve is actuated it routes fluid to and from an actuator and tank. The fluid's pressure will rise to meet any resistance, since the pump has a constant output. If the pressure rises too high, fluid returns to tank through a pressure relief valve. Multiple control valves may be stacked in series. This type of circuit can use inexpensive, constant displacement pumps.

Closed-loop: Motor-return is connected directly to the pump-inlet. To keep up pressure on the low pressure side, the circuits have a charge pump (a small gearpump) that supplies cooled and filtered oil to the low pressure side. Closed-loop circuits are generally used for hydrostatic transmissions in mobile applications. Advantages: No directional valve and better response, the circuit can work with higher pressure. The pump swivel angle covers both positive and negative flow direction. Disadvantages: The pump cannot be utilized for any other hydraulic function in an easy way and cooling can be a problem due to limited exchange of oil flow. High power closed loop systems generally must have a 'flush-valve' assembled in the circuit in order to exchange much more flow than the basic leakage flow from the pump and the motor, for increased cooling and filtering. The flush valve is normally integrated in the motor housing to get a cooling effect for the oil that is rotating in the motor housing itself. The losses in the motor housing from rotating effects and losses in the ball bearings can be considerable as motor speeds will reach 4000-5000 rev/min or even more at maximum vehicle speed. The leakage flow as well as the extra flush flow must be supplied by the charge pump. A large charge pump is thus very important if the transmission is designed for high pressures and high motor speeds. High oil temperature is usually a major problem when using hydrostatic transmissions at high vehicle speeds for longer periods, for instance when transporting the machine from one work place to the other. High oil temperatures for long periods will drastically reduce the lifetime of the transmission. To keep down the oil temperature, the system pressure during transport must be lowered, meaning that the minimum displacement for the motor must be limited to a reasonable value. Circuit pressure during transport around 200-250 bar is recommended.

Closed loop systems in mobile equipment are generally used for the transmission as an alternative to mechanical and hydrodynamic (converter) transmissions. The advantage is a stepless gear ratio (continuously variable speed/torque) and a more flexible control of the gear ratio depending on the load and operating conditions. The hydrostatic transmission is generally limited to around 200 kW maximum power, as the total cost gets too high at higher power compared to a hydrodynamic transmission. Large wheel loaders for instance and heavy machines are therefore usually equipped with converter transmissions. Recent technical achievements for the converter transmissions have improved the efficiency and developments in the software have also improved the characteristics, for example selectable gear shifting programs during operation and more gear steps, giving them characteristics close to the hydrostatic transmission.

Hydrostatic transmissions for earth moving machines, such as for track loaders, are often equipped with a separate 'inch pedal' that is used to temporarily increase the diesel engine rpm while reducing the vehicle speed in order to increase the available hydraulic power output for the working hydraulics at low speeds and increase the tractive effort. The function is similar to stalling a converter gearbox at high engine rpm. The inch function affects the preset characteristics for the 'hydrostatic' gear ratio versus diesel engine rpm.

Components

Hydraulic pump

Hydraulic pumps supply fluid to the components in the system. Pressure in the system develops in reaction to the load. Hence, a pump rated for 5,000 psi is capable of maintaining flow against a load of 5,000 psi.

Pumps have a power density about ten times greater than an electric motor (by volume). They are powered by an electric motor or an engine, connected through gears, belts, or a flexible elastomeric coupling to reduce vibration.

Common types of hydraulic pumps to hydraulic machinery applications are;

- Gear pump: cheap, durable (especially in g-rotor form), simple. Less efficient, because they are constant (fixed) displacement, and mainly suitable for pressures below 20 MPa (3000 psi).

- Vane pump: cheap and simple, reliable. Good for higher-flow low-pressure output.

- Axial piston pump: many designed with a variable displacement mechanism, to vary output flow for automatic control of pressure. There are various axial piston pump designs, including swashplate (sometimes referred to as a valveplate pump) and checkball (sometimes referred to as a wobble plate pump). The most common is the swashplate pump. A variable-angle swashplate causes the pistons to reciprocate a greater or lesser distance per rotation, allowing output flow rate and pressure to be varied (greater displacement angle causes higher flow rate, lower pressure, and vice versa).

- Radial piston pump: normally used for very high pressure at small flows.

Piston pumps are more expensive than gear or vane pumps, but provide longer life operating at higher pressure, with difficult fluids and longer continuous duty cycles. Piston pumps make up one half of a hydrostatic transmission.

Control valves

Directional control valves route the fluid to the desired actuator. They usually consist of a spool inside a cast iron or steel housing. The spool slides to different positions in the housing, and intersecting grooves and channels route the fluid based on the spool's position.

The spool has a central (neutral) position maintained with springs; in this position the supply fluid is blocked, or returned to tank. Sliding the spool to one side routes the hydraulic fluid to an actuator and provides a return path from the actuator to tank. When the spool is moved to the opposite direction the supply and return paths are switched. When the spool is allowed to return to neutral (center) position the actuator fluid paths are blocked, locking it in position.

Directional control valves are usually designed to be stackable, with one valve for each hydraulic cylinder, and one fluid input supplying all the valves in the stack.

Tolerances are very tight in order to handle the high pressure and avoid leaking, spools typically have a clearance with the housing of less than a thousandth of an inch (25 µm). The valve block will be mounted to the machine's frame with a three point pattern to avoid distorting the valve block and jamming the valve's sensitive components.

The spool position may be actuated by mechanical levers, hydraulic pilot pressure, or solenoids which push the spool left or right. A seal allows part of the spool to protrude outside the housing, where it is accessible to the actuator.

The main valve block is usually a stack of off the shelf directional control valves chosen by flow capacity and performance. Some valves are designed to be proportional (flow rate proportional to valve position), while others may be simply on-off. The control valve is one of the most expensive and sensitive parts of a hydraulic circuit.

- Pressure relief valves are used in several places in hydraulic machinery; on the return circuit to maintain a small amount of pressure for brakes, pilot lines, etc... On hydraulic cylinders, to prevent overloading and hydraulic line/seal rupture. On the hydraulic reservoir, to maintain a small positive pressure which excludes moisture and contamination.

- Pressure regulators reduce the supply pressure of hydraulic fluids as needed for various circuits.

- Sequence valves control the sequence of hydraulic circuits; to ensure that one hydraulic cylinder is fully extended before another starts its stroke, for example.

- Shuttle valves provide a logical or function.

- Check valves are one-way valves, allowing an accumulator to charge and maintain its pressure after the machine is turned off, for example.

- Pilot controlled Check valves are one-way valve that can be opened (for both directions) by a foreign pressure signal. For instance if the load should not be held by the check valve anymore. Often the foreign pressure comes from the other pipe that is connected to the motor or cylinder.

- Counterbalance valves are in fact a special type of pilot controlled check valve. Whereas the check valve is open or closed, the counterbalance valve acts a bit like a pilot controlled flow control.

- Cartridge valves are in fact the inner part of a check valve; they are off the shelf components with a standardized envelope, making them easy to populate a proprietary valve block. They are available in many configurations; on/off, proportional, pressure relief, etc. They generally screw into a valve block and are electrically controlled to provide logic and automated functions.

- Hydraulic fuses are in-line safety devices designed to automatically seal off a hydraulic line if pressure becomes too low, or safely vent fluid if pressure becomes too high.

- Auxiliary valves in complex hydraulic systems may have auxiliary valve blocks to handle various duties unseen to the operator, such as accumulator charging, cooling fan operation, air conditioning power, etc. They are usually custom valves designed for the particular machine, and may consist of a metal block with ports and channels drilled. Cartridge valves are threaded into the ports and may be electrically controlled by switches or a microprocessor to route fluid power as needed.

Actuators

- Hydraulic cylinder

- Swashplates are used in 'hydraulic motors' requiring highly accurate control and also in 'no stop' continuous (360°) precision positioning mechanisms. These are frequently driven by several hydraulic pistons acting in sequence.

- Hydraulic motor (a pump plumbed in reverse)

- Hydrostatic transmission

- Brakes

Reservoir

The hydraulic fluid reservoir holds excess hydraulic fluid to accommodate volume changes from: cylinder extension and contraction, temperature driven expansion and contraction, and leaks. The reservoir is also designed to aid in separation of air from the fluid and also work as a heat accumulator to cover losses in the system when peak power is used. Design engineers are always pressured to reduce the size of hydraulic reservoirs, while equipment operators always appreciate larger reservoirs. Reservoirs can also help separate dirt and other particulate from the oil, as the particulate will generally settle to the bottom of the tank. Some designs include dynamic flow channels on the fluid's return path that allow for a smaller reservoir.

Accumulators

Accumulators are a common part of hydraulic machinery. Their function is to store energy by using pressurized gas. One type is a tube with a floating piston. On one side of the piston is a charge of pressurized gas, and on the other side is the fluid. Bladders are used in other designs. Reservoirs store a system's fluid.

Examples of accumulator uses are backup power for steering or brakes, or to act as a shock absorber for the hydraulic circuit.

Hydraulic fluid

Also known as tractor fluid, hydraulic fluid is the life of the hydraulic circuit. It is usually petroleum oil with various additives. Some hydraulic machines require fire resistant fluids, depending on their applications. In some factories where food is prepared, either an edible oil or water is used as a working fluid for health and safety reasons.

In addition to transferring energy, hydraulic fluid needs to lubricate components, suspend contaminants and metal filings for transport to the filter, and to function well to several hundred degrees Fahrenheit or Celsius.

Filters

Filters are an important part of hydraulic systems. Metal particles are continually produced by mechanical components and need to be removed along with other contaminants.

Filters may be positioned in many locations. The filter may be located between the reservoir and the pump intake. Blockage of the filter will cause cavitation and possibly failure of the pump. Sometimes the filter is located between the pump and the control valves. This arrangement is more expensive, since the filter housing is pressurized, but eliminates cavitation problems and protects the control valve from pump failures. The third common filter location is just before the return line enters the reservoir. This location is relatively insensitive to blockage and does not require a pressurized housing, but contaminants that enter the reservoir from external sources are not filtered until passing through the system at least once.filters are used from 7 micron to 15 micron depends upon the viscosity grade of hydraulic oil.

Tubes, pipes and hoses

Hydraulic tubes are seamless steel precision pipes, specially manufactured for hydraulics. The tubes have standard sizes for different pressure ranges, with standard diameters up to 100 mm. The tubes are supplied by manufacturers in lengths of 6 m, cleaned, oiled and plugged. The tubes are interconnected by different types of flanges (especially for the larger sizes and pressures), welding cones/nipples (with o-ring seal), several types of flare connection and by cut-rings. In larger sizes, hydraulic pipes are used. Direct joining of tubes by welding is not acceptable since the interior cannot be inspected.

Hydraulic pipe is used in case standard hydraulic tubes are not available. Generally these are used for low pressure. They can be connected by threaded connections, but usually by welds. Because of the larger diameters the pipe can usually be inspected internally after welding. Black pipe is non-galvanized and suitable for welding.

Hydraulic hose is graded by pressure, temperature, and fluid compatibility. Hoses are used when pipes or tubes can not be used, usually to provide flexibility for machine operation or maintenance. The hose is built up with rubber and steel layers. A rubber interior is surrounded by multiple layers of woven wire and rubber. The exterior is designed for abrasion resistance. The bend radius of hydraulic hose is carefully designed into the machine, since hose failures can be deadly, and violating the hose's minimum bend radius will cause failure. Hydraulic hoses generally have steel fittings swaged on the ends. The weakest part of the high pressure hose is the connection of the hose to the fitting. Another disadvantage of hoses is the shorter life of rubber which requires periodic replacement, usually at five to seven year intervals.

Tubes and pipes for hydraulic applications are internally oiled before the system is commissioned. Usually steel piping is painted outside. Where flare and other couplings are used, the paint is removed under the nut, and is a location where corrosion can begin. For this reason, in marine applications most piping is stainless steel.

Seals, fittings and connections

Components of a hydraulic system [sources (e.g. pumps), controls (e.g. valves) and actuators (e.g. cylinders)] need connections that will contain and direct the hydraulic fluid without leaking or losing the pressure that makes them work. In some cases, the components can be made to bolt together with fluid paths built-in. In more cases, though, rigid tubing or flexible hoses are used to direct the flow from one component to the next. Each component has entry and exit points for the fluid involved (called ports) sized according to how much fluid is expected to pass through it.

There are a number of standardized methods in use to attach the hose or tube to the component. Some are intended for ease of use and service, others are better for higher system pressures or control of leakage. The most common method, in general, is to provide in each component a female-threaded port, on each hose or tube a female-threaded captive nut, and use a separate adapter fitting with matching male threads to connect the two. This is functional, economical to manufacture, and easy to service.

Fittings serve several purposes;

- To join components with ports of different sizes.

- To bridge different standards; O-ring boss to JIC, or pipe threads to face seal, for example.

- To allow proper orientation of components, a 90°, 45°, straight, or swivel fitting is chosen as needed. They are designed to be positioned in the correct orientation and then tightened.

- To incorporate bulkhead hardware to pass the fluid through an obstructing wall.

- A quick disconnect fitting may be added to a machine without modification of hoses or valves

A typical piece of machinery or heavy equipment may have thousands of sealed connection points and several different types:

- Pipe fittings, the fitting is screwed in until tight, difficult to orient an angled fitting correctly without over or under tightening.

- O-ring boss, the fitting is screwed into a boss and orientated as needed, an additional nut tightens the fitting, washer and o-ring in place.

- Flare fittings, are metal to metal compression seals deformed with a cone nut and pressed into a flare mating.

- Face seal, metal flanges with a groove and o-ring seal are fastened together.

- Beam seals are costly metal to metal seals used primarily in aircraft.

- Swaged seals, tubes are connected with fittings that are swaged permanently in place. Primarily used in aircraft.

Elastomeric seals (O-ring boss and face seal) are the most common types of seals in heavy equipment and are capable of reliably sealing 6000+ psi (40+ MPa) of fluid pressure.

Basic calculations

Hydraulic power is defined as flow times pressure. The hydraulic power supplied by a pump:

- Power = (P x Q) ÷ 600

where power is in kilowatts [kW], P pressure in bars, and Q is the flow in liters per minute. For example, a pump delivers 180 lit/min and the pressure equals 250 bar, therefore the power of the pump is 75 kW.

When calculating the power input to the pump, the total pump efficiency ηtotal must be included. This efficiency is the product of volumetric efficiency, ηvol and the hydromechanical efficiency, ηhm. Power input = Power output ÷ ηtotal. The average for axial piston pumps, ηtotal = 0.87. In the example the power source, for example a diesel engine or an electric motor, must be capable of delivering at least 75 ÷ 0.87 = 86 [kW]. The hydraulic motors and cylinders that the pump supplies with hydraulic power also have efficiencies and the total system efficiency (without including the pressure drop in the hydraulic pipes and valves) will end up at approx. 0.75. Cylinders normally have a total efficiency around 0.95 while hydraulic axial piston motors 0.87, the same as the pump. In general the power loss in a hydraulic energy transmission is thus around 25% or more at ideal viscosity range 25-35 [cSt].

Calculation of the required max. power output for the diesel engine, rough estimation:

(1) Check the max. powerpoint, i.e. the point where pressure times flow reach the max. value.

(2) Ediesel = (Pmax·Qtot)÷η.

Qtot = calculate with the theoretical pump flow for the consumers not including leakages at max. power point.

Pmax = actual pump pressure at max. power point.

Note: η is the total efficiency = (output mechanical power ÷ input mechanical power). For rough estimations, η = 0.75. Add 10-20% (depends on the application) to this power value.

(3) Calculate the required pumpdisplacement from required max. sum of flow for the consumers in worst case and the diesel engine rpm in this point. The max. flow can differ from the flow used for calculation of the diesel engine power. Pump volumetric efficiency average, piston pumps: ηvol= 0.93.

Pumpdisplacement Vpump= Qtot ÷ ndiesel ÷ 0.93.

(4) Calculation of prel. cooler capacity: Heat dissipation from hydraulic oil tanks, valves, pipes and hydraulic components is less than a few percent in standard mobile equipment and the cooler capacity must include some margins. Minimum cooler capacity, Ecooler = 0.25Ediesel

At least 25% of the input power must be dissipated by the cooler when peak power is utilized for long periods. In normal case however, the peak power is used for only short periods, thus the actual cooler capacity required might be considerably less. The oil volume in the hydraulic tank is also acting as a heat accumulator when peak power is used. The system efficiency is very much dependent on the type of hydraulic work tool equipment, the hydraulic pumps and motors used and power input to the hydraulics may vary a lot. Each circuit must be evaluated and the load cycle estimated. New or modified systems must always be tested in practical work, covering all possible load cycles. An easy way of measuring the actual average power loss in the system is to equip the machine with a test cooler and measure the oil temperature at cooler inlet, oil temperature at cooler outlet and the oil flow through the cooler, when the machine is in normal operating mode. From these figures the test cooler power dissipation can be calculated and this is equal to the power loss when temperatures are stabilized. From this test the actual required cooler can be calculated to reach specified oil temperature in the oil tank. One problem can be to assemble the measuring equipment inline, especially the oil flow meter.

History

Joseph Bramah patented the hydraulic press in 1795.[1] While working at Bramah's shop, Henry Maudslay suggested a cup leather packing.[2] Because it produced superior results, the hydraulic press eventually displaced the steam hammer from metal forging.[3]

To supply small scale power that was impractical for individual steam engines, central station hydraulic systems were developed. Hydraulic power was used to operate cranes and other machinery in British ports and elsewhere in Europe. The largest hydraulic system was in London. Hydraulic power was used extensively in Bessemer steel production. Hydraulic power was also used for elevators, to operate canal locks and rotating sections of bridges.[1][3] Some of these systems remained in use well into the twentieth century.

Harry Franklin Vickers was called the "Father of Industrial Hydraulics" by ASME.

See also

- Automatic transmission

- Brake fluid

- High-density solids pump

- Hydraulic brake

- Hydraulic drive system

- National Fluid Power Association

- Sidelifter

| ||||||||||||||

References and notes

- 1 2 McNeil, Ian (1990). An Encyclopedia of the History of Technology. London: Routledge. p. 961. ISBN 0-415-14792-1.

- ↑ Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269

- 1 2 Hunter, Louis C.; Bryant, Lynwood (1991). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730-1930, Vol. 3: The Transmission of Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-08198-9.

- Hydraulic Power System Analysis, A. Akers, M. Gassman, & R. Smith, Taylor & Francis, New York, 2006, ISBN 0-8247-9956-9

External links

- Facts worth knowing about hydraulics, Danfoss Hydraulics, 1.4Mb pdf file

- On-line re-print of U.S. Army Field Manual 5-499

- Information about Fluid Power is also available on the National Fluid *Power Association web-site nfpa.com