Hydraulic jump

A hydraulic jump is a phenomenon in the science of hydraulics which is frequently observed in open channel flow such as rivers and spillways. When liquid at high velocity discharges into a zone of lower velocity, a rather abrupt rise occurs in the liquid surface. The rapidly flowing liquid is abruptly slowed and increases in height, converting some of the flow's initial kinetic energy into an increase in potential energy, with some energy irreversibly lost through turbulence to heat. In an open channel flow, this manifests as the fast flow rapidly slowing and piling up on top of itself similar to how a shockwave forms.

The phenomenon is dependent upon the initial fluid speed. If the initial speed of the fluid is below the critical speed, then no jump is possible. For initial flow speeds which are not significantly above the critical speed, the transition appears as an undulating wave. As the initial flow speed increases further, the transition becomes more abrupt, until at high enough speeds, the transition front will break and curl back upon itself. When this happens, the jump can be accompanied by violent turbulence, eddying, air entrainment, and surface undulations, or waves.

There are two main manifestations of hydraulic jumps and historically different terminology has been used for each. However, the mechanisms behind them are similar because they are simply variations of each other seen from different frames of reference, and so the physics and analysis techniques can be used for both types.

The different manifestations are:

- The stationary hydraulic jump – rapidly flowing water transitions in a stationary jump to slowly moving water as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

- The tidal bore – a wall or undulating wave of water moves upstream against water flowing downstream as shown in Figures 3 and 4. If considered from a frame of reference which moves with the wave front, you can see that this case is physically similar to a stationary jump.

A related case is a cascade – a wall or undulating wave of water moves downstream overtaking a shallower downstream flow of water as shown in Figure 5. If considered from a frame of reference which moves with the wave front, this is amenable to the same analysis as a stationary jump.

These phenomena are addressed in an extensive literature from a number of technical viewpoints.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Classes of hydraulic jumps

Hydraulic jumps can be seen in both a stationary form, which is known as a "hydraulic jump", and a dynamic or moving form, which is known as a positive surge or "hydraulic jump in translation".[14] They can be described using the same analytic approaches and are simply variants of a single phenomenon.[13][14][16]

Moving hydraulic jump

A tidal bore is a hydraulic jump which occurs when the incoming tide forms a wave (or waves) of water that travel up a river or narrow bay against the direction of the current.[14] As is true for hydraulic jumps in general, bores take on various forms depending upon the difference in the waterlevel upstream and down, ranging from an undular wavefront to a shock-wave-like wall of water.[7] Figure 3 shows a tidal bore with the characteristics common to shallow upstream water – a large elevation difference is observed. Figure 4 shows a tidal bore with the characteristics common to deep upstream water – a small elevation difference is observed and the wavefront undulates. In both cases the tidal wave moves at the speed characteristic of waves in water of the depth found immediately behind the wave front. A key feature of tidal bores and positive surges is the intense turbulent mixing induced by the passage of the bore front and by the following wave motion.[17]

Another variation of the moving hydraulic jump is the cascade. In the cascade, a series of roll waves or undulating waves of water moves downstream overtaking a shallower downstream flow of water.

Stationary hydraulic jump

The stationary hydraulic jump is most frequently seen on rivers and on engineered features such as outfalls of dams and irrigation works. They occur when a flow of liquid at high velocity discharges into a zone of the river or engineered structure which can only sustain a lower velocity. When this occurs, the water slows in a rather abrupt rise (a step or standing wave) on the liquid surface.[15]

Comparing the characteristics before and after, one finds:

| Characteristic | Before the jump | After the jump |

|---|---|---|

| fluid speed | supercritical (faster than the wave speed) also known as shooting or superundal | subcritical also known as tranquil or subundal |

| fluid height | low | high |

| flow | typically smooth turbulent | typically turbulent flow (rough and choppy) |

The other stationary hydraulic jump occurs when a rapid flow encounters a submerged object which throws the water upwards. The mathematics behind this form is more complex and will need to take into account the shape of the object and the flow characteristics of the fluid around it.

Analysis of the hydraulic jump on a liquid surface

In spite of the apparent complexity of the flow transition, application of simple analytic tools to a two dimensional analysis is effective in providing analytic results which closely parallel both field and laboratory results. Analysis shows:

- Height of the jump: the relationship between the depths before and after the jump as a function of flow rate[16]

- Energy loss in the jump

- Location of the jump on a natural or an engineered structure

- Character of the jump: undular or abrupt

Height of the jump

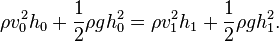

The height of the jump is derived from the application of the equations of conservation of mass and momentum.[16] There are several methods of predicting the height of a hydraulic jump.[1][2][3][4][8][13][16][18]

They all reach common conclusions that:

- The ratio of the water depth before and after the jump depend solely on the ratio of velocity of the water entering the jump to the speed of the wave over-running the moving water.

- The height of the jump can be many times the initial depth of the water.

For a known flow rate  as shown by the figure below, the approximation that the momentum flux is the same just up- and downstream of the energy principle yields an expression of the energy loss in the hydraulic jump. Hydraulic jumps are commonly used as energy dissipators downstream of dam spillways.

as shown by the figure below, the approximation that the momentum flux is the same just up- and downstream of the energy principle yields an expression of the energy loss in the hydraulic jump. Hydraulic jumps are commonly used as energy dissipators downstream of dam spillways.

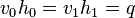

- Applying the continuity principle

In fluid dynamics, the equation of continuity is effectively an equation of conservation of mass. Considering any fixed closed surface within an incompressible moving fluid, the fluid flows into a given volume at some points and flows out at other points along the surface with no net change in mass within the space since the density is constant. In case of a rectangular channel, then the equality of mass flux upstream ( ) and downstream (

) and downstream ( ) gives:

) gives:

or

or

with  the fluid density,

the fluid density,  and

and  the depth-averaged flow velocities upstream and downstream, and

the depth-averaged flow velocities upstream and downstream, and  and

and  the corresponding water depths.

the corresponding water depths.

- Conservation of momentum flux

For a straight prismatic rectangular channel, the conservation of momentum flux across the jump, assuming constant density, can be expressed as:

In rectangular channel, such conservation equation can be further simplified to dimensionless M-y equation form, which is widely used in hydraulic jump analysis in open channel flow.

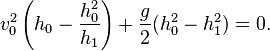

Jump height in terms of flow

Dividing by constant  and introducing the result from continuity gives

and introducing the result from continuity gives

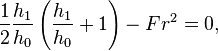

which, after some algebra, simplifies to:

where  Here

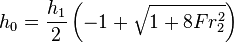

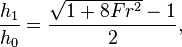

Here  is the dimensionless Froude number, and relates inertial to gravitational forces in the upstream flow. Solving this quadratic yields:

is the dimensionless Froude number, and relates inertial to gravitational forces in the upstream flow. Solving this quadratic yields:

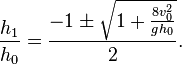

Negative answers do not yield meaningful physical solutions, so this reduces to:

so

so

known as Bélanger equation. The result may be extended to an irregular cross-section.[16]

This produces three solution classes:

- When

, then

, then  (i.e., there is no jump)

(i.e., there is no jump) - When

, then

, then  (i.e., there is a negative jump – this can be shown as not conserving energy and is only physically possible if some force were to accelerate the fluid at that point)

(i.e., there is a negative jump – this can be shown as not conserving energy and is only physically possible if some force were to accelerate the fluid at that point) - When

, then

, then  (i.e., there is a positive jump)

(i.e., there is a positive jump)

This is equivalent to the condition that  . Since the

. Since the  is the speed of a shallow gravity wave, the condition that

is the speed of a shallow gravity wave, the condition that  is equivalent to stating that the initial velocity represents supercritical flow (Froude number > 1) while the final velocity represents subcritical flow (Froude number < 1).

is equivalent to stating that the initial velocity represents supercritical flow (Froude number > 1) while the final velocity represents subcritical flow (Froude number < 1).

- Undulations downstream of the jump

Practically this means that water accelerated by large drops can create stronger standing waves (undular bores) in the form of hydraulic jumps as it decelerates at the base of the drop. Such standing waves, when found downstream of a weir or natural rock ledge, can form an extremely dangerous "keeper" with a water wall that "keeps" floating objects (e.g., logs, kayaks, or kayakers) recirculating in the standing wave for extended periods.

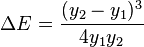

Energy dissipation by a hydraulic jump

One of the most important engineering applications of the hydraulic jump is to dissipate energy in channels, dam spillways, and similar structures so that the excess kinetic energy does not damage these structures. The rate of energy dissipation or head loss across a hydraulic jump is a function of the hydraulic jump inflow Froude number and the height of the jump.[13]

The mathematical formula for Energy loss in hydraulic jump is as follows:

Location of hydraulic jump in a streambed or an engineered structure

In the design of a dam the energy of the fast-flowing stream over a spillway must be partially dissipated to prevent erosion of the streambed downstream of the spillway, which could ultimately lead to failure of the dam. This can be done by arranging for the formation of a hydraulic jump to dissipate energy. To limit damage, this hydraulic jump normally occurs on an apron engineered to withstand hydraulic forces and to prevent local cavitation and other phenomena which accelerate erosion.

In the design of a spillway and apron, the engineers select the point at which a hydraulic jump will occur. Obstructions or slope changes are routinely designed into the apron to force a jump at a specific location. Obstructions are unnecessary, as the slope change alone is normally sufficient. To trigger the hydraulic jump without obstacles, an apron is designed such that the flat slope of the apron retards the rapidly flowing water from the spillway. If the apron slope is insufficient to maintain the original high velocity, a jump will occur.

Two methods of designing an induced jump are common:

- If the downstream flow is restricted by the down-stream channel such that water backs up onto the foot of the spillway, that downstream water level can be used to identify the location of the jump.

- If the spillway continues to drop for some distance, but the slope changes such that it will no longer support supercritical flow, the depth in the lower subcritical flow region is sufficient to determine the location of the jump.

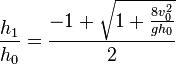

In both cases, the final depth of the water is determined by the downstream characteristics. The jump will occur if and only if the level of inflowing (supercritical) water level ( ) satisfies the condition:

) satisfies the condition:

-

= Upstream Froude Number

= Upstream Froude Number - g = acceleration due to gravity (essentially constant for this case)

- h = height of the fluid (

= initial height while

= initial height while  = upstream height)

= upstream height)

Air entrainment in hydraulic jumps

The hydraulic jump is characterised by a highly turbulent flow. Macro-scale vortices develop in the jump roller and interact with the free surface leading to air bubble entrainment, splashes and droplets formation in the two-phase flow region.[20][21] The air–water flow is associated with turbulence, which can also lead to sediment transport. The turbulence may be strongly affected by the bubble dynamics. Physically, the mechanisms involved in these processes are complex.

The air entrainment occurs in the form of air bubbles and air packets entrapped at the impingement of the upstream jet flow with the roller. The air packets are broken up in very small air bubbles as they are entrained in the shear region, characterised by large air contents and maximum bubble count rates.[22] Once the entrained bubbles are advected into regions of lesser shear, bubble collisions and coalescence lead to larger air entities that are driven towards the free-surface by a combination of buoyancy and turbulent advection.

Tabular summary of the analytic conclusions

| Amount upstream flow is supercritical (i.e., prejump Froude Number) | Ratio of height after to height before jump | Descriptive characteristics of jump | Fraction of energy dissipated by jump[9] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1.0 | 1.0 | No jump; flow must be supercritical for jump to occur | none |

| 1.0–1.7 | 1.0–2.0 | Standing or undulating wave | < 5% |

| 1.7–2.5 | 2.0–3.1 | Weak jump (series of small rollers) | 5% – 15% |

| 2.5–4.5 | 3.1–5.9 | Oscillating jump | 15% – 45% |

| 4.5–9.0 | 5.9–12.0 | Stable clearly defined well-balanced jump | 45% – 70% |

| > 9.0 | > 12.0 | Clearly defined, turbulent, strong jump | 70% – 85% |

NB: the above classification is very rough. Undular hydraulic jumps have been observed with inflow/prejump Froude numbers up to 3.5 to 4.[13][14]

Hydraulic jump variations

A number of variations are amenable to similar analysis:

Shallow fluid hydraulic jumps

- The hydraulic jump in your sink

Figure 2 above illustrates a daily example of a hydraulic jump can be seen in the sink. Around the place where the tap water hits the sink, you will see a smooth-looking flow pattern. A little further away, you will see a sudden "jump" in the water level. This is a hydraulic jump.

The nature of this jump differs from those previously discussed in the following ways:

- The water is flowing radially. As a result, it continuously grows shallower and slows due to friction (the Froude number drops) up to the point where the jump occurs.

- The flow depth is thin enough that the surface tension can no longer be neglected, changing the wave solution conclusions. The higher speed of the surface tension waves bleed off the high frequency component, making an undular jump the dominant form.[23]

Changes in the behavior of the jump can be observed by changing the flow rate.

Internal wave hydraulic jumps

Hydraulic jumps in abyssal fan formation

Turbidity currents can result in internal hydraulic jumps (i.e., hydraulic jumps as internal waves in fluids of different density) in abyssal fan formation. The internal hydraulic jumps have been associated with salinity or temperature induced stratification as well as with density differences due to suspended materials. When the bed slope over which the turbidity current flattens, the slower rate of flow is mirrored by increased sediment deposition below the flow, producing a gradual backward slope. Where a hydraulic jump occurs, the signature is an abrupt backward slope, corresponding to the rapid reduction in the flow rate at the point of the jump.[24]

Atmospheric hydraulic jumps

A related situation is the Morning Glory cloud observed, for example, in Northern Australia, sometimes called an undular jump.[14]

Industrial and recreational applications for hydraulic jumps

Industrial

The hydraulic jump is the most commonly used choice of design engineers for energy dissipation below spillways and outlets. A properly designed hydraulic jump can provide for 60-70% energy dissipation of the energy in the basin itself, limiting the damage to structures and the streambed. Even with such efficient energy dissipation, stilling basins must be carefully designed to avoid serious damage due to uplift, vibration, cavitation, and abrasion. An extensive literature has been developed for this type of engineering.[5][6][11][13]

Recreational

While travelling down river, kayaking and canoeing paddlers will often stop and playboat in standing waves and hydraulic jumps. The standing waves and shock fronts of hydraulic jumps make for popular locations for such recreation.

Similarly, kayakers and surfers have been known to ride tidal bores up rivers.

See also

References and notes

- 1 2 Douglas, J.F.; Gasiorek, J.M.; Swaffield, J.A. (2001). Fluid Mechanics (4th ed.). Essex: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-582-41476-8.

- 1 2 Faber, T.E. (1995). Fluid Dynamics for Physicists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42969-2.

- 1 2 Faulkner, L.L. (2000). Practical Fluid Mechanics for Engineering Applications. Basil, Switzerland: Marcel Dekker AG. ISBN 0-8247-9575-X.

- 1 2 Fox, R.W.; McDonald, A.T. (1985). Introduction to Fluid Mechanics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-88598-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Hager, Willi H. (1995). Energy Dissipaters and Hydraulic Jump. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-5410-198-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Khatsuria, R.M. (2005). Hydraulics of Spillways and Energy Dissipaters. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-5789-0.

- 1 2 Lighthill, James (1978). Waves in Fluids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29233-6.

- 1 2 Roberson, J.A.; Crowe, C.T (1990). Engineering Fluid Mechanics. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-38124-X.

- 1 2 Streeter, V.L.; Wylie, E.B. (1979). Fluid Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-062232-9.

- ↑ Vennard, John K. (1963). Elementary Fluid Mechanics (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- 1 2 3 4 Vischer, D.L.; Hager, W.H. (1995). Energy Dissipaters. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema. ISBN 0-8247-5789-0.

- ↑ White, Frank M. (1986). Fluid Mechanics. McGraw Hill, Inc. ISBN 0-07-069673-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Chanson, H. (2004). The Hydraulic of Open Channel Flow: an Introduction (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-5978-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chanson, H. (2009). "Current Knowledge In Hydraulic Jumps And Related Phenomena. A Survey of Experimental Results". European Journal of Mechanics B/Fluids 28 (2,): 191–210. Bibcode:2009EJMF...28..191C. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2008.06.004.

- 1 2 Murzyn, F.; Chanson, H. (2009). "Free-Surface Fluctuations in Hydraulic Jumps: Experimental Observations". Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 33 (7): 1055–1064. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2009.06.003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chanson, H. (2012). Momentum Considerations in Hydraulic Jumps and Bores. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 138, No. 4, pp. 382-385 (DOI 10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0000409) (ISSN 0733-9437). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)IR.1943-4774.0000409. ISSN 0733-9437.

- ↑ Koch, C.; Chanson, H. (2009). "Turbulence Measurements in Positive Surges and Bores". Journal of Hydraulic Research (IAHR) 47 (1): 29–40. doi:10.3826/jhr.2009.2954.

- ↑ This section outlines the approaches at an overview level only.

- ↑ "Energy loss in a hydraulic jump". sdsu. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Chanson, H.; Brattberg, T. (2000). "Experimental Study of the Air-Water Shear Flow in a Hydraulic Jump". International Journal of Multiphase Flow 26 (4): 583–607. doi:10.1016/S0301-9322(99)00016-6.

- ↑ Murzyn, F.; Chanson, H. (2009). "Two-phase gas-liquid flow properties in the hydraulic jump: Review and perspectives". In S. Martin and J.R. Williams. Multiphase Flow Research. Hauppauge NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers. Chapter 9, pp. 497–542. ISBN 978-1-60692-448-8.

- ↑ Chanson, H. (2007). "Bubbly Flow Structure in Hydraulic Jump". European Journal of Mechanics B/Fluids 26 (3): 367–384. Bibcode:2007EJMF...26..367C. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2006.08.001.

- ↑ Surface tension effects can be seen by looking closely at the region inside the hydraulic jump. There you will observe thin waves radiating radially and axially from the point of water impact.

- ↑ Kostic, Svetlana; Parker, Gary (2006). "The Response of Turbidity Currents to a Canyon-Fan Transition: Internal Hydraulic Jumps and Depositional Signatures". Journal of Hydraulic Research 44 (5): 631–653. doi:10.1080/00221686.2006.9521713.

Further reading

- Chanson, Hubert (2009). "Current Knowledge In Hydraulic Jumps And Related Phenomena. A Survey of Experimental Results". European Journal of Mechanics B/Fluids 28 (2): 191–210. Bibcode:2009EJMF...28..191C. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2008.06.004.