Pocket watch

A pocket watch (or pocketwatch) is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

They were the most common type of watch from their development in the 16th century until wristwatches became popular after World War I during which a transitional design, trench watches, were used by the military. Pocket watches generally have an attached chain to allow them to be secured to a waistcoat, lapel, or belt loop, and to prevent them from being dropped. Watches were also mounted on a short leather strap or fob, when a long chain would have been cumbersome or likely to catch on things. This fob could also provide a protective flap over their face and crystal. Women's watches were normally of this form, with a watch fob that was more decorative than protective. Chains were frequently decorated with a silver or enamel pendant, often carrying the arms of some club or society, which by association also became known as a fob. Ostensibly "practical" gadgets such as a watch winding key, vesta case or a cigar cutter also appeared on watch chains, although usually in an overly decorated style. Also common are fasteners designed to be put through a buttonhole and worn in a jacket or waistcoat, this sort being frequently associated with and named after train conductors.

An early reference to the pocket watch is in a letter in November 1462 from the Italian clockmaker Bartholomew Manfredi to the Marchese di Mantova Federico Gonzaga, where he offers him a "pocket clock" better than that belonging to the Duke of Modena. By the end of the 15th century, spring-driven clocks appeared in Italy, and in Germany. Peter Henlein, a master locksmith of Nuremberg, was regularly manufacturing pocket watches by 1524. Thereafter, pocket watch manufacture spread throughout the rest of Europe as the 16th century progressed. Early watches only had an hour hand, the minute hand appearing in the late 17th century.[1][2] The first American pocket watches with machine made parts were manufactured by Henry Pitkin with his brother in the later 1830s.

History

The first timepieces to be worn, made in 16th-century Europe, were transitional in size between clocks and watches.[3] These 'clock-watches' were fastened to clothing or worn on a chain around the neck. They were heavy drum shaped brass cylinders several inches in diameter, engraved and ornamented. They had only an hour hand. The face was not covered with glass, but usually had a hinged brass cover, often decoratively pierced with grillwork so the time could be read without opening. The movement was made of iron or steel and held together with tapered pins and wedges, until screws began to be used after 1550. Many of the movements included striking or alarm mechanisms. The shape later evolved into a rounded form; these were later called Nuremberg eggs.[3] Still later in the century there was a trend for unusually shaped watches, and clock-watches shaped like books, animals, fruit, stars, flowers, insects, crosses, and even skulls (Death's head watches) were made.

Styles changed in the 17th century and men began to wear watches in pockets instead of as pendants (the woman's watch remained a pendant into the 20th century).[4][5] This is said to have occurred in 1675 when Charles II of England introduced waistcoats.[6] To fit in pockets, their shape evolved into the typical pocket watch shape, rounded and flattened with no sharp edges. Glass was used to cover the face beginning around 1610. Watch fobs began to be used, the name originating from the German word fuppe, a small pocket.[5] The watch was wound and also set by opening the back and fitting a key to a square arbor, and turning it.

Until the second half of the 18th century, watches were luxury items; as an indication of how highly they were valued, English newspapers of the 18th century often include advertisements offering rewards of between one and five guineas merely for information that might lead to the recovery of stolen watches. By the end of the 18th century, however, watches (while still largely hand-made) were becoming more common; special cheap watches were made for sale to sailors, with crude but colorful paintings of maritime scenes on the dials.

Up to the 1720s, almost all watch movements were based on the verge escapement, which had been developed for large public clocks in the 14th century. This type of escapement involved a high degree of friction and did not include any kind of jewelling to protect the contacting surfaces from wear. As a result, a verge watch could rarely achieve any high standard of accuracy. (Surviving examples mostly run very fast, often gaining an hour a day or more.) The first widely used improvement was the cylinder escapement, developed by the Abbé de Hautefeuille early in the 18th century and applied by the English maker George Graham. Then, towards the end of the 18th century, the lever escapement (invented by Thomas Mudge in 1759) was put into limited production by a handful of makers including Josiah Emery (a Swiss based in London) and Abraham-Louis Breguet. With this, a domestic watch could keep time to within a minute a day. Lever watches became common after about 1820, and this type is still used in most mechanical watches today.

In 1857 the American Watch Company in Waltham, Massachusetts introduced the Waltham Model 57, the first to use interchangeable parts. This cut the cost of manufacture and repair. Most Model 57 pocket watches were in a coin silver ("one nine fine"), a 90% pure silver alloy commonly used in dollar coinage, slightly less pure than the British (92.5%) sterling silver, both of which avoided the higher purity of other types of silver to make circulating coins and other utilitarian silver objects last longer with heavy use.

Watch manufacture was becoming streamlined; the Japy family of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, led the way in this, and soon afterwards the newborn American watch industry developed much new machinery, so that by 1865 the American Watch Company (afterwards known as Waltham) could turn out more than 50,000 reliable watches each year. This development drove the Swiss out of their dominating position at the cheaper end of the market, compelling them to raise the quality of their products and establish themselves as the leaders in precision and accuracy instead.

Use in railroading in the United States

The rise of railroading during the last half of the 19th century led to the widespread use of pocket watches. A famous train wreck on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway in Kipton, Ohio on April 19, 1891 occurred because one of the engineers' watches had stopped for four minutes. The railroad officials commissioned Webb C. Ball as their Chief Time Inspector, in order to establish precision standards and a reliable timepiece inspection system for Railroad chronometers. This led to the adoption in 1893 of stringent standards for pocket watches used in railroading. These railroad-grade pocket watches, as they became colloquially known, had to meet the General Railroad Timepiece Standards adopted in 1893 by almost all railroads. These standards read, in part:

- "...open faced, size 16 or 18, have a minimum of 17 jewels, adjusted to at least five positions, keep time accurately to within 30 seconds a week, adjusted to temps of 34 °F (1 °C) to 100 °F (38 °C), have a double roller, steel escape wheel, lever set, regulator, winding stem at 12 o'clock, and have bold black Arabic numerals on a white dial, with black hands."

Types of pocket watches

There are two main styles of pocket watch, the hunter-case pocket watch, and the open-face pocket watch.

Open-face watches

An open-faced, or Lépine,[7] watch, is one in which the case lacks a metal cover to protect the crystal. It is typical for an open-faced watch to have the pendant located at 12:00 and the sub-second dial located at 6:00. Occasionally, a watch movement intended for a hunting case (with the winding stem at 3:00 and sub second dial at 6:00) will have an open-faced case. Such watch is known as a "sidewinder." Alternatively, such a watch movement may be fitted with a so-called conversion dial, which relocates the winding stem to 12:00 and the sub-second dial to 3:00. After 1908, watches approved for railroad service were required to be cased in open-faced cases with the winding stem at 12:00.

Hunter-case watches

A hunter-case pocket watch ("hunter") is a case with a spring-hinged circular metal lid or cover, that closes over the watch-dial and crystal, protecting them from dust, scratches and other damage or debris. The majority of antique and vintage hunter-case watches have the lid-hinges at the 9 o'clock position and the stem, crown and bow of the watch at the 3 o'clock position. Modern hunter-case pocket watches usually have the hinges for the lid at the 6 o'clock position and the stem, crown and bow at the 12 o'clock position, as with open-face watches. In both styles of watch-cases, the sub-seconds dial was always at the 6 o'clock position. A hunter-case pocket watch with a spring-ring chain is pictured at the top of this page.

An intermediate type, known as the demi-hunter (demi hunter, half hunter or half-hunter), is a case style in which the outer lid has a glass panel or hole in the centre giving a view of the hands. The hours are marked, often in blue enamel, on the outer lid itself; thus with this type of case one can tell the time without opening the lid.

Types of watch movements

Key-wind, key-set movements

The very first pocket watches, since their creation in the 16th century, up until the third quarter of the 19th century, had key-wind and key-set movements. A watch key was necessary to wind the watch and to set the time. This was usually done by opening the caseback and putting the key over the winding-arbor (which was set over the watch's winding-wheel, to wind the mainspring) or by putting the key onto the setting-arbor, which was connected with the minute-wheel and turned the hands. Some watches of this period had the setting-arbor at the front of the watch, so that removing the crystal and bezel was necessary to set the time. Watch keys are the origin of the class key, common paraphernalia for American high-school and university graduation.

Many keywind watch movements make use of a fusee, to improve isochronism. The fusee is a specially cut conical pulley attached by a fine chain to the mainspring barrel. When the spring is fully wound (and its torque the highest), the full length of the chain is wrapped around the fusee and the force of the mainspring is exerted on the smallest diameter portion of the fusee cone. As the spring unwinds and its torque decreases, the chain winds back onto the mainspring barrel and pulls on an increasingly larger diameter portion of the fusee. This provides a more uniform amount of torque on the watch train, and thus results in more consistent balance amplitude and better isochronism. A fusee is a practical necessity in watches using a verge escapement, and can also provide considerable benefit with a lever escapement and other high precision types of escapements (Hamiltons WWII era Model 21 chronometer used a fusee in combination with a detent escapement).

Keywind watches are also commonly seen with conventional going barrels and other types of mainspring barrels, particularly in American watchmaking.

Stem-wind, stem-set movements

Invented by Adrien Philippe in 1842 and commercialized by Patek Philippe & Co. in the 1850s, the stem-wind, stem-set movement did away with the watch key which was a necessity for the operation of any pocket watch up to that point. The first stem-wind and stem-set pocket watches were sold during the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and the first owners of these new kinds of watches were Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Stem-wind, stem-set movements are the most common type of watch-movement found in both vintage and modern pocket watches.

The mainstream transition to the use of stem-wind, stem-set watches occurred at around the same time as the end of the manufacture and use of the fusee watch. Fusee chain-driven timing was replaced with a mainspring of better quality spring steel (commonly known as the "going barrel") allowing for a more even release of power to the escape mechanism. However the reader of this article should not be misled to think that the winding and setting functions are directly related to the balance wheel and balance spring. The balance wheel and balance spring provide a separate function: to regulate the timing (or escape) of the movement.

Stem-wind, lever-set movements

Mandatory for all railroad watches after roughly 1908, this kind of pocket watch was set by opening the crystal and bezel and pulling out the setting-lever (most hunter cases have levers accessible without removing the crystal or bezel), which was generally found at either the 10 or 2 o'clock positions on open-faced watches, and at 5:00 on hunting cased watches. Once the lever was pulled out, the crown could be turned to set the time. The lever was then pushed back in and the crystal and bezel were closed over the dial again. This method of time setting on pocket watches was preferred by American and Canadian railroads, as lever setting watches make accidental time changes impossible. After 1908, lever setting was generally required for new watches entering service on American railroads.

Stem-wind, pin-set movements

Much like the lever-set movements, these pocket watches had a small pin or knob next to the watch-stem that had to be depressed before turning the crown to set the time and releasing the pin when the correct time had been set. This style of watch is occasionally referred to as "nail set", as the set button must be pressed using a finger.

Jeweled movements

- For more information, see Mechanical watch

Watches of any quality will be jeweled. A jewel in a mechanical watch is a small, shaped piece of a hard mineral. Ruby and sapphire are most common. Diamond, garnet, and glass are also seen. Starting in the early 20th century, synthetic jewels were almost universally used. Before that time, low grade natural jewels which were unsuitable as gemstones were used. In either case, the jewels have virtually no monetary value.

The most common types of jewels are hole jewels. Hole jewels are disks (normally flying saucer shaped) which have a carefully shaped and sized hole. The pivot of an arbor rides in this hole. The jewel provides an extremely smooth and hard surface which is very wear resistant, and when properly lubricated, very low friction. Thus, hole jewels both reduce friction and wear on the moving parts of a watch.

The other basic jewel types are cap jewels, roller jewels, and pallet jewels.

Cap jewels are always paired with hole jewels, and always with a conically shaped pivot. The cap jewels are so called because they "cap" the hole jewels and control the axial movement of the arbor, preventing the shoulder of the pivot contacting the hole jewel. For a properly designed hole and cap jewel system, the arbor pivot bears on the cap jewel as a pin point on a thin film of oil. Thus, a hole and cap jewel offer lower friction and better performance across different positions compared with simply a hole jewel.

The roller jewel, also called the impulse jewel or simply impulse pin, is a thin rod of ruby or sapphire, usually in the shape of a letter "D". The roller jewel is responsible for coupling the motion of the balance wheel to that of the pallet fork.

Pallet jewels are on the pallet fork and interact with the escape wheel. They are the surfaces which, 5 times a second in a typical escapement, lock the gear train of the watch and then transfer power to the balance wheel.

A jeweled watch with a lever escapement should contain at least 7 jewels. The seven jewels are; 2 hole jewels and 2 cap jewels for the pivots of the balance wheel staff (arbor), one impulse (roller) jewel, and 2 pallet jewels.

More highly jeweled watches add jewels to other pivots, starting with the pallet fork, then the escape wheel, fourth wheel, third wheel, then finally the center wheel. Jeweling like this to the third wheel adds eight jewels, giving 15 jewels in total. Jeweling to the center wheel adds two more giving 17 jewels in total. Thus, a 17 jewel watch is considered to be fully jeweled.

With American makers, however, it was common on low-end movements to jewel to the third wheel on only the top (visible) plate of the watch. This gives a total of 11 jewels, but looks identical to a 15 jewel watch unless the dial is removed. Since watches with 15 jewels and less are often not marked as to the jewel count, extreme caution must be exercised when purchasing movements which appear to be 15 jewels.

Additional jewels beyond 17 are used to either add cap jewels, or to jewel the mainspring barrel of the watch. Watches with 19 jewels, particularly those made by Elgin and Waltham, will often have a jeweled mainspring barrel. Alternatively a 19 jewel watch will have additional cap jewels on the escape wheel. 21 jewel watches commonly have cap jewels on both the pallet fork and escape wheel. 23 jewel watches will have a jeweled barrel and fully capped escapement. The timekeeping value of jewels beyond 17 for a time-only movement is often debated.

Complicated movements will often have additional jewels which do serve useful purposes.

Greater jewel counts are often associated with better quality watch movements. While it is true that expensive movements often have higher jewel counts, the jewels themselves are not the reason for this. The jewels themselves add essentially no monetary value, and beyond 17 offer a negligible improvement in timekeeping ability and in movement life. Most of the cost of a more expensive watch is associated with better quality finishing and, more importantly, with a greater number of adjustments.

Adjusted movements

Pocket watch movements are occasionally engraved with the word "Adjusted", or "Adjusted to n positions". This means that the watch has been tuned to keep time under various positions and conditions. There are eight possible adjustments:

- Dial up.

- Dial down.

- Pendant up.

- Pendant down.

- Pendant left.

- Pendant right.

- Temperature (from 34–100 degrees Fahrenheit).

- Isochronism (the ability of the watch to keep time, regardless of the mainspring's level of tension).

Positional adjustments are attained by careful poising (ensuring even weight distribution) of the balance-hairspring system as well as careful control of the shape and polish on the balance pivots. All of this achieves an equalization of the effect of gravity on the watch in various positions. Positional adjustments are achieved through careful adjustment of each of these factors, provided by repeated trials on a timing machine. Thus, adjusting a watch to position requires many hours of labor, increasing the cost of the watch. Medium grade watches were commonly adjusted to 3 positions (dial up, dial down, pendant up) while high grade watches were commonly adjusted to 5 positions (dial up, dial down, stem up, stem left, stem right) or even all 6 positions. Railroad watches were required, after 1908, to be adjusted to 5 positions. 3 positions were the general requirement before that time.

Early watches used a solid steel balance. As temperature increased, the solid balance expanded in size, changing the moment of inertia and changing the timing of the watch. In addition, the hairspring would lengthen, decreasing its spring constant. This problem was initially solved through the use of the compensation balance. The compensation balance consisted of a ring of steel sandwiched to a ring of brass. These rings were then split in two places. The balance would, at least theoretically, actually decrease in size with heating to compensate for the lengthening of the hairspring. Through careful adjustment of the placement of the balance screws (brass or gold screws placed in the rim of the balance), a watch could be adjusted to keep time the same at both hot (100 °F) and cold (32°) temperatures. Unfortunately, a watch so adjusted would run slow at temperatures between these two. The problem was completely solved through the use of special alloys for the balance and hairspring which were essentially immune to thermal expansion. Such an alloy is used in Hamilton's 992E and 992B.

Isochronism was occasionally improved through the use of a stopworks, a system designed to only allow the mainspring to operate within its center (most consistent) range. The most common method of achieving isochronism is through the use of the Breguet overcoil. which places part of the outermost turn of the hairspring in a different plane from the rest of the spring. This allows the hairspring to "breathe" more evenly and symmetrically. Two types of overcoils are found - the gradual overcoil and the Z-Bend. The gradual overcoil is obtained by imposing a two gradual twists to the hairspring, forming the rise to the second plane over half the circumference; and the Z-bend does this by imposing two kinks of complementary 45 degree angles, accomplishing a rise to the second plane in about three spring section heights. The second method is done for esthetic reasons and is much more difficult to perform. Due to the difficulty with forming an overcoil, modern watches often use a slightly less effective "dogleg", which uses a series of sharp bends (in plane) to place part of the outermost coil out of the way of the rest of the spring.

Decline in popularity

Pocket watches are not common in modern times, having been superseded by wristwatches. Up until the start of the 20th century, though, the pocket watch was predominant and the wristwatch was considered feminine and unmanly. In men's fashions, pocket watches began to be superseded by wristwatches around the time of World War I, when officers in the field began to appreciate that a watch worn on the wrist was more easily accessed than one kept in a pocket. A watch of transitional design, combining features of pocket watches and modern wristwatches, was called trench watch or "wristlet". However, pocket watches continued to be widely used in railroading even as their popularity declined elsewhere.

The use of pocket watches in a professional environment came to an ultimate end in approximately 1943. The Royal Navy of the British military distributed to their sailors Waltham pocket watches, which were 9 jewel movements, with black dials, and numbers coated with radium for visibility in the dark, in anticipation of the eventual D-Day invasion. The same Walthams were ordered by the Canadian military as well. Hanhart was a brand which was used by the Germans, although the German U-Boat captains (and their allied counterparts) were more likely to use stopwatches for timing torpedo runs.

For a few years in the late 1970s and 1980s three-piece suits for men returned to fashion, and this led to small resurgence in pocket watches, as some men actually used the vest pocket for its original purpose. Since then, some watch companies continue to make pocket watches. As vests have long since fallen out of fashion (in the US) as part of formal business wear, the only available location for carrying a watch is in a trouser pocket. The more recent advent of mobile phones and other gadgets that are worn on the waist has diminished the appeal of carrying an additional item in the same location, especially as such pocketable gadgets usually have timekeeping functionality themselves.

In some countries a gift of a gold-cased pocket watch is traditionally awarded to an employee upon their retirement.[8]

The pocketwatch has regained popularity due to steampunk, a subcultural movement embracing the arts and fashions of the Victorian era, where pocketwatches were nearly ubiquitous. It is now considered an eccentricity to carry a pocketwatch.

Most complicated pocket watches

- The Vacheron Constantin Reference 57260 (2015) — 57 complications

- Patek Philippe Calibre 89 (1989) — 33 complications

- Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication (1933) — 24 complications

See also

References

- ↑ "Watch, Mechanical", Science and Technology, How It Works 19 (3rd ed.), Marshall Cavendish, 2003, p. 2651, ISBN 0-7614-7333-5 in How it Works, ISBN 0-7614-7314-9.

- ↑ Campbell, Gordon (2006), The Grove encyclopedia of decorative arts 1, Oxford University Press, p. 253, ISBN 0-19-518948-5.

- 1 2 Milham 1945, pp. 133–37.

- ↑ Perez, Carlos (2001). "Artifacts of the Golden Age, part 1". Carlos's Journal. TimeZone. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- 1 2 Milham 1945, pp. 213–15.

- ↑ "Pocketwatch". Encyclopedia of Antiques. Clocks and Watches. Old and Sold.

- ↑ "Lépine watch", Glossary, Fondation de la Haute horlogerie.

- ↑ Van Horn, Carl (2003). Work in America M–Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 236. ISBN 1-57607-676-8.

Bibliography

- Milham, Willis I (1945), Time and Timekeepers, New York: MacMillan, ISBN 0-7808-0008-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to pocket watch. |

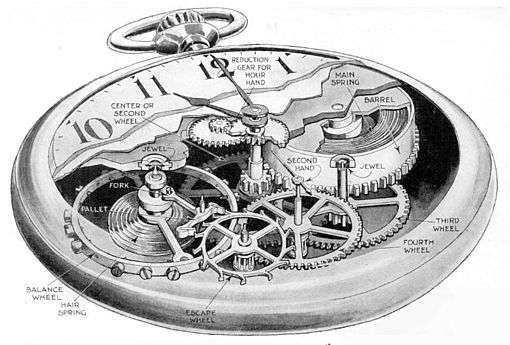

- "Perfect Timepiece", Popular Mechanics, December 1931. Illustration of workings of common mechanical pocket watch.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|