Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Hungary portal | ||||||||||||||||||||

The Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin,[1] also Hungarian conquest[2] or Hungarian land-taking[3] (Hungarian: honfoglalás: "conquest of the homeland")[4] was a series of historical events ending with the settlement of the Hungarian people in Central Europe at the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries. Before the arrival of the Hungarians, three early medieval powers, the First Bulgarian Empire, East Francia and Moravia had fought each other for control of the Carpathian Basin. They occasionally hired Hungarian horsemen as soldiers. Therefore, the Hungarians who dwelled in the eastern regions of the Pontic steppes were familiar with their future homeland when their "land-taking" started.

The Hungarian conquest started in the context of a "late or 'small' migration of peoples".[1] Contemporary sources attest that the Hungarians crossed the Carpathian Mountains following a joint attack in 894 or 895 by the Pechenegs and Bulgarians against them. They first took control over the lowlands east of the river Danube and attacked and occupied Pannonia (the region to the west of the river) in 900. They exploited internal conflicts in Moravia and annihilated this state sometime between 902 and 906.

The Hungarians strengthened their control over the Carpathian Basin by defeating a Bavarian army in a battle fought at Brezalauspurc on July 4, 907. They launched a series of plundering raids between 899 and 955 and also targeted the Byzantine Empire between 943 and 971. However, they gradually settled in the Basin and established a Christian monarchy, the Kingdom of Hungary around 1000.

Sources

Written sources

Byzantine authors were the first to record these events.[5] The earliest work is Emperor Leo the Wise's Tactics, finished around 904, which recounts the Bulgarian-Byzantine war of 894–896, a military conflict directly preceding the Hungarians' departure from the Pontic steppes.[6] Nearly contemporary narration[5] can be read in the Continuation of the Chronicle by George the Monk.[7] However, De Administrando Imperio ("On Governing the Empire") provides the most detailed account.[8] It was compiled under the auspices of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in 951 or 952.[9]

Works written by clergymen in the successor states of the Carolingian Empire narrate events closely connected to the conquest.[5] The Annals of Fulda which ends in 901 is the earliest among them.[10] A letter from Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg to Pope John IX in 900 also refers to the conquering Hungarians, but it is often regarded as a fake.[11] Abbot Regino of Prüm who compiled his World Chronicle around 908[12] sums up his knowledge on the Hungarians in a sole entry under the year 889.[11] Another valuable source is Bishop Liutprand of Cremona's Antapodosis ("Retribution") from around 960.[13][14] Aventinus, a 16th-century historian provides information not known from other works,[15] which suggests that he used now-lost sources.[15][16] However, his reliability is suspect.[17]

An Old Church Slavonic compilation of Lives of saints preserved an eyewitness account on the Bulgarian-Byzantine war of 894–896.[18][19] The first[20] Life of Saint Naum, written around 924, contains nearly contemporary information on the fall of Moravia caused by Hungarian invasions, although its earliest extant copy is from the 15th century.[19] Similarly late manuscripts (the oldest of which was written in the 14th century) offer the text of the Russian Primary Chronicle, a historical work completed in 1113.[21] It provides information based on earlier Byzantine and Moravian[22] sources.[21]

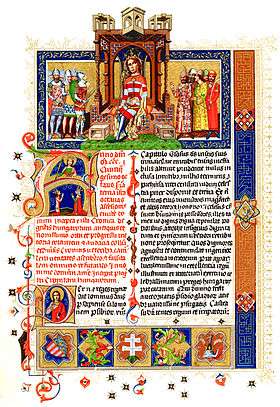

The Hungarians themselves initially preserved the memory of the major events in "the form of folk songs and ballads" (C. A. Macartney).[23] The earliest local chronicle was compiled in the late 11th century.[24] It exists now in more than one variant, its original version several times extended and rewritten during the Middle Ages.[25][26] For instance, the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle contains texts from the 11th-century chronicle.[25][27]

An anonymous author's Gesta Hungarorum ("Deeds of the Hungarians"), written before 1200,[28] is the earliest extant local chronicle.[27][29] However, this "most misleading" example "of all the early Hungarian texts" (C. A. Macartney) contains much information that cannot be confirmed based on contemporaneous sources.[30] Around 1283 Simon of Kéza, a priest at the Hungarian royal court wrote the next surviving chronicle.[27] He claims that the Hungarians were closely related to the Huns, earlier conquerors of the Carpathian Basin.[31] Accordingly, in his narration, the Hungarian invasion is in fact a second conquest of the same territory by the same people.[27]

Archaeology

Graves of the first generations of the conquering Hungarians were identified in the Carpathian Basin, but fewer than ten definitely Hungarian cemeteries have been unearthed in the Pontic steppes.[32] Most Hungarian cemeteries include 25 or 30 inhumation graves, but isolated burials were common.[33][34] Adult males (and sometimes women and children)[35] were buried together with either parts of their horses or with harness and other objects symbolizing a horse.[36][37] The graves also yielded decorated silver belts, sabretaches furnished with metal plates, pear-shaped stirrups and other metal works.[38] Many of these objects had close analogues in the contemporaneous multiethnic "Saltovo-Mayaki culture"[35] of the Pontic steppes.[39] Most cemeteries from the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries are concentrated in the Upper Tisza region and in the plains along the rivers Rába and Vág, for instance, at Tarcal, Tiszabezdéd, Naszvad (Nesvady, Slovakia) and Gyömöre,[40] but early small cemeteries were also unearthed at Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), Marosgombás (Gâmbaș) and other Transylvanian sites.[41]

Some decades after the Hungarian conquest, a new synthesis of earlier cultures, the "Bijelo Brdo culture" spread in all over the Carpathian Basin, with its characteristic jewellery, including S-shaped earrings.[42][43] The lack of archaeological finds connected to horses in "Bijelo Brdo" graves is another feature of these cemeteries.[44] The earliest "Bijelo Brdo" assemblages are dated via unearthed coins to the rule of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in the middle of the 10th century.[45] Early cemeteries of the culture were unearthed, for instance, at Beremend and Csongrád in Hungary, at Dévény (Devín) and Zsitvabesenyő (Bešenov) in Slovakia, at Gyulavarsánd (Varşand) and Várfalva (Moldoveneşti) in Romania and at Vukovár (Vukovar) and Gorbonok (Kloštar Podravski) in Croatia.[46]

Etymology

The Hungarians adopted the ancient (Celtic, Dacian or Germanic) names of the longest rivers in the Carpathian Basin from a Slavic-speaking population.[48] For instance, the Hungarian names of the rivers Danube (Duna), Dráva, Garam, Maros, Olt, Száva, Tisza and Vág were borrowed from Slavs.[48][49] The Hungarians also adopted a great number of hydronyms of Slavic origin, including Balaton ("swamp"), Beszterce ("swift river"), Túr ("aurochs' stream") and Zagyva ("sooty river").[48][50][51] Place names of Slavic origin abound across the Carpathian Basin.[52] For instance, Csongrád ("black fortress"), Nógrád ("new fortress"), Visegrád ("citadel") and other early medieval fortresses bore a Slavic name, while the name of Keszthely preserved the Latin word for fortress (castellum) with Slavic mediation.[52][53]

Hungarian society experienced fundamental changes in many fields (including animal husbandry, agriculture and religion) in the centuries following the "Land-taking". These changes are reflected in the significant number of terms borrowed from local Slavs.[54][55] About 20% of the Hungarian vocabulary is of Slavic origin,[44] including the Hungarian words for sheep-pen (akol), yoke (iga) and horseshoe (patkó).[47] Similarly, the Hungarian name of vegetables, fruits and other cultivated plants, as well as many Hungarian terms connected to agriculture are Slavic loanwords, including káposzta ("cabbage"), szilva ("plum"), zab ("oats"), széna ("hay") and kasza ("scythe").[47][55][56]

Besides the Slavs, the presence of a German-speaking population can be demonstrated based on toponyms.[57] For instance, the Hungarians adopted the Germanized form of the name of the river Vulka (whose name is of Slavic origin) and the document known as the Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians from around 870 lists Germanic place names in Pannonia, including Salapiugin ("bend of the Zala") and Mosaburc ("fortress in the marshes").[58] Finally, the name of the Barca, Barót and other rivers could be either Turkic[51] or Slavic.[59]

Background

Pre-Conquest Hungarians

The Continuation of the Chronicle by George the Monk contains the earliest certain[60] reference to the Hungarians.[61] It states that Hungarian warriors intervened in a conflict between the Byzantine Empire and the Bulgarians on the latter's behalf in the Lower Danube region in 836 or 837.[62] The first known Hungarian raid in Central Europe was recorded in the Annals of St. Bertin.[63] It writes of "enemies, called Hungarians, hitherto unknown"[64] who ravaged King Louis the German's realm in 862.[63] Vajay, Spinei and other historians argue that Rastislav of Moravia, at war with Louis the German, hired Hungarians to invade East Francia.[63][65] Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg clearly states in his letter of around 900 that the Moravians often allied with the Hungarians against the Germans.[65]

For many years [the Moravians] have in fact perpetrated the very crime of which they have only once falsely accused us. They themselves have taken in a large number of Hungarians and have shaved their own heads according to their heathen customs and they have sent them against our Christians, overcoming them, leading some away as captives, killing others, while still others, imprisoned, perished of hunger and thirst.

Porphyrogenitus mentions that the Hungarians dwelled in a territory that they called "Atelkouzou" until their invasion across the Carpathians.[67][68][69] He adds that it was located in the territory where the rivers Barouch, Koubou, Troullos, Broutos and Seretos[70] run.[71][72] Although the identification of the first two rivers with the Dnieper and the Southern Bug is not unanimously accepted, the last three names without doubt refer to the rivers Dniester, Prut and Siret.[72] In the wider region, at Subotsi on the river Adiamka, three graves (one of them belonging to a male buried with the skull and legs of his horse) are attributed to pre-conquest Hungarians.[72] However, these tombs may date to the 10th century.[73]

The Hungarians were organized into seven tribes that formed a confederation.[74] Constantine Porphyrogenitus mentions this number.[75] Anonymous seems to have preserved the Hungarian "Hetumoger" ("Seven Hungarians") denomination of the tribal confederation, although he writes of "seven leading persons"[76] jointly bearing this name instead of a political organization.[75]

The Hetumoger confederation was strengthened by the arrival of the Kabars,[74] who (according to Constantine) joined the Hungarians following their unsuccessful riot against the Khazar Khaganate.[77] The Hungarians and the Kabars are mentioned in the longer version of the Annals of Salzburg,[78] which relates that the Hungarians fought around Vienna, while the Kabars fought nearby at Culmite in 881.[79] Madgearu proposes that Kavar groups were already settled in the Tisza plain within the Carpathian Basin around 881, which may have given rise to the anachronistic reference to Cumans in the Gesta Hungarorum at the time of the Hungarian conquest.[80]

The Hetumoger confederation was under a dual leadership, according to Ibn Rusta and Gardizi (two Muslim scholars from the 10th and 11th centuries, respectively, whose geographical books preserved texts from an earlier work written by al-Jayhani from Bukhara).[81][82][83] The Hungarians' nominal or sacred leader was styled kende, while their military commander bore the title gyula.[82][84] The same authors add that the gyula commanded an army of 20,000 horsemen,[85] but the reliability of this number is uncertain.[86]

Regino of Prüm and other contemporary authors portray the 9th-century Hungarians as nomadic warriors.[87] Emperor Leo the Wise underlines the importance of horses to their military tactics.[88] Analysis of horse skulls found in Hungarian warriors graves has not revealed any significant difference between these horses and Western breeds.[89] Regino of Prüm states that the Hungarians knew "nothing about fighting hand-to-hand in formation or taking besieged cities",[90] but he underlines their archery skills.[91] Remains indicate that composite bows were the Hungarians' most important weapons.[92] In addition, slightly curved sabres were unearthed in many warrior tombs from the period.[93] Regino of Prüm noted the Hungarians' preference for deceptions such as apparent retreat in battle.[91] Contemporaneous writers also recounted their viciousness, represented by the slaughter of adult males in settlement raids.[36]

[The Hungarians] are armed with swords, body armor, bows and lances. Thus, in battles most of them bear double arms, carrying the lances high on their shoulders and holding the bows in their hands. They make use of both as need requires, but when pursued they use their bows to great advantage. Not only do they wear armor themselves, but the horses of their illustrious men are covered in front with iron or quilted material. They devote a great deal of attention and training to archery on horse-back. A huge herd of horses, ponies and mares, follows them, to provide both food and milk and, at the same time, to give the impression of a multitude.

Carpathian Basin on the eve of the Conquest

The Carpathian Basin was controlled from the 560s by the Avars,[95] a Turkic-speaking people.[96] Upon their arrival in the region, they imposed their authority over the Gepids who had dominated the territories east of the river Tisza.[97] However, the Gepids survived up until the second half of the 9th century, according to a reference in the Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians to their groups dwelling in Lower Pannonia around 870.[57]

The Avars initially were nomadic horsemen, but both large cemeteries used by three or four generations and a growing number of settlements attest to their adoption of a sedentary (non-nomadic) way of life from the 8th century.[98][99] The Avars' power was destroyed between 791 and 795 by Charlemagne,[100] who occupied Transdanubia and attached it to his empire.[101] Archaeological investigation of early medieval rural settlements at Balatonmagyaród, Nemeskér and other places in Transdanubia demonstrate that their main features did not change with the fall of the Avar Khaganate.[102] New settlements appeared in the former borderlands with cemeteries characterized by objects with clear analogues in contemporary Bavaria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Moravia and other faraway territories.[102] A manor defended by timber walls (similar to noble courts of other parts of the Carolingian Empire) was unearthed at Zalaszabar.[102]

Avar groups who remained under the rule of their khagan were frequently attacked by Slav warriors.[103] Therefore, the khagan asked Charlemagne to let his people settle in the region between Szombathely and Petronell in Pannonia.[104] His petition was accepted in 805.[104] The Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians lists the Avars among the peoples under the ecclesiastic jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Salzburg around 870.[105] According to Pohl, it "simply proved impossible to keep up an Avar identity after Avar institutions and the high claims of their tradition had failed."[106] The growing number of archaeological evidence in Transdanubia also presumes Avar population in the Carpathian Basin at the eve of the 10th century.[107] Archaeological findings suggesting that there is a substantial late Avar presence on the Great Hungarian Plain, however it is difficult to determine their proper chronology.[107]

A charter issued in 860 by King Louis the German for the Mattsee Abbey may well attest that the Onogurs (another people of Turkic origin) were also present in the territory.[108] The charter refers to the "Marches of the Wangars" (marcha uuangariourum) situated in the westernmost regions of the Carpathian Basin.[109] The Wangar denomination seems to reflect the Slavic form of the Onogurs' ethnonym.[108]

According to Béla Miklós Szőke's theory, the detailed description of the Magyars by western contemporary sources and the immediate Hungarian intervention in local wars give the presumption that the Hungarians had already lived on the eastern territories of the Carpathian Basin since the middle of the 9th century.[110] Regarding the right location of early Hungarian settlements, the Arabic geographer al-Jayhani (only snippets of his work survived in other Muslim authors' papers)[111] in the 870s placed the Hungarians between Don and Danube rivers.[110] Szőke identifies al-Jayhani's Danube with the middle Danube region, as opposed to the previously assumed lower Danube region, because following al-Jayhani's description the Christian Moravians were the western neighbors of the Magyars.[110]

Based on the extant Hungarian chronicles, it is clear that more than one (occasionally extended) list existed of the peoples inhabiting the Carpathian Basin at the time of the Hungarian landtaking.[112] Anonymous, for instance, first writes of the "Slavs, Bulgarians, Vlachs and the shepherds of the Romans"[113] as inhabiting the territory,[114][115] but later he refers to "a people called Kozar"[116] and to the Székelys.[112] Similarly, Simon of Kéza first lists the "Slavs, Greeks, Germans, Moravians and Vlachs",[117][118] but later adds that the Székelys also lived in the territory.[119] According to C. A. Macartney, those lists were based on multiple sources and do not document the real ethnic conditions of the Carpathian Basin around 900.[120] According to Ioan-Aurel Pop, Simon of Kéza listed the peoples who inhabited the lands that the Hungarian conquered and the nearby territories.[121]

The territories attached to the Frankish Empire were initially governed by royal officers and local chieftains.[122] A Slavic prince named Pribina received large estates along the river Zala around 840.[123] He promoted the colonization of his lands,[124] and also erected Mosaburg, a fortress in the marshes.[123] Initially defended by timber walls, this "castle complex"[125] (András Róna-Tas) became an administrative center. It was strengthened by drystone walls at the end of the century. Four churches surrounded by cemeteries were unearthed in and around the settlement. At least one of them continued to be used up to the 11th century.[126]

Pribina died fighting the Moravians in 861, and his son, Kocel inherited his estates.[127] The latter was succeeded around 876 by Arnulf, a natural son of Carloman, king of East Francia.[128] Under his rule, Moravian troops interved into the conflict known as the "Wilhelminer War" and "laid waste from the Raab eastward", between 882 and 884, according to the Annals of Fulda.[129][130]

Moravia emerged in the 820s[131] under its first known ruler, Mojmir I.[123] His successor, Rastislav, developed Moravia's military strength. He promoted the proselytizing activities of the Byzantine brothers, Constantine and Methodius in an attempt to seek independence from East Francia.[123][132] Moravia reached its "peak of importance" under Svatopluk I[133] (870–894) who expanded its frontiers in all directions.[134]

Moravia's core territory is located in the regions on the northern Morava river, in the territory of present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia.[135] However, Constantine Porphyrogenitus places "great Moravia, the unbaptized"[136] somewhere in the regions beyond Belgrade and Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia).[137] His report supported further theories on Moravia's location.[138] For instance, Kristó and Senga propose the existence of two Moravias (one in the north and other one in the south),[139] while Boba, Bowlus and Eggers argue that Moravia's core territory is in the region of the southern Morava river, in present-day Serbia.[140] The existence of a southern Moravian realm is not supported by artifacts, while strongholds unearthed at Mikulcice, Pohansko and other areas to the north of the Middle Danube point at the existence of a power center in those regions.[141]

In addition to East Francia and Moravia, the first Bulgarian Empire was the third power deeply involved in the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century.[142] A late 10th-century Byzantine lexicon known as Suda adds that Krum of Bulgaria attacked the Avars from the southeast around 803.[143] The Royal Frankish Annals narrates that the Abodrites inhabiting "Dacia on the Danube"[144] (most probably along the lower courses of the river Tisza) sought the assistance of the Franks against the Bulgars in 824.[145] Bulgarian troops also invaded Pannonia, "expelled the Slavic chieftains and appointed Bulgar governors instead"[146] in 827.[147][148] An inscription at Provadia refers to a Bulgarian military leader named Onegavonais drowning in the Tisza around the same time.[149] The emerging power of Moravia brought about a rapprochement between Bulgaria and East Francia in the 860s.[150] For instance, King Arnulf of East Francia sent an embassy to the Bulgarians in 892 in order "to renew the former peace and to ask that they should not sell salt to the Moravians".[151] The latter request suggests that the route from the salt mines of the Eastern Carpathians to Moravia was controlled around that time by the Bulgarians.[152][153]

The anonymous author of the Gesta Hungarorum, instead of Svatopluk I of Moravia and other rulers known from contemporary sources, writes of personalities and polities that are not mentioned by chroniclers working at the end of the 9th century.[154] For instance, he refers to Menumorut residing in the castle of Bihar (Biharia, Romania), to Zobor "duke of Nitra by the grace of the Duke of the Czechs",[155] and to Gelou "a certain Vlach"[156] ruling over Transylvania.[154] Although early medieval fortresses were unearthed at Bihar and other places east of the Tisza, none of them definitively date to the 9th century.[157] For instance, in the case of Doboka (Dăbâca), two pairs of bell-shaped pendants with analogues in sites in Austria, Bulgaria and Poland have been unearthed, but Florin Curta dates them to the 9th century, while Alexandru Madgearu to the period between 975 and 1050.[158][159]

The Hungarian conquest

Prelude (892–c. 895)

Three main theories attempt to explain the reasons for the "Hungarian land-taking".[160] One argues that it was an intended military operation, prearranged following previous raids, with the express purpose of occupying a new homeland.[160] This view (represented, for instance, by Bakay and Padányi) mainly follows the narration of Anonymous and later Hungarian chronicles.[161] The opposite view maintains that a joint attack by the Pechenegs and the Bulgarians forced the Hungarians' hand.[162] Kristó, Tóth and the theory's other followers refer to the unanimous testimony provided by the Annals of Fulda, Regino of Prüm and Porphyrogenitus on the connection between the Hungarians' conflict with the Bulgar-Pecheneg coalition and their withdrawal from the Pontic steppes.[163][164] An intermediate theory proposes that the Hungarians had for decades been considering a westward move when the Bulgarian-Pecheneg attack accelerated their decision to leave the Pontic steppes.[165] For instance Róna-Tas argues, "[the] fact that, despite a series of unfortunate events, the Magyars managed to keep their heads above water goes to show that they were indeed ready to move on" when the Pechenegs attacked them.[166]

In fact, following a break of eleven years, the Hungarians returned to the Carpathian Basin in 892.[77] They came to assist Arnulf of East Francia against Svatopluk I of Moravia.[77][167] Widukind of Corvey and Liutprand of Cremona condemned the Frankish monarch for destroying the defense lines built along the empire's borders, because this also enabled the Hungarians to attack East Francia within a decade.[168]

Meanwhile Arnulf (…) could not overcome Sviatopolk, duke of the Moravians (…); and – alas! – having dismantled those very well fortified barriers which (…) are called "closures" by the populace. Arnulf summoned to his aid the nation of the Hungarians, greedy, rash, ignorant of almighty God but well versed in every crime, avid only for murder and plunder (…).

A late source,[17] Aventinus adds that Kurszán (Cusala), "king of the Hungarians" stipulated that his people would only fight the Moravians if they received the lands they were to occupy.[167] Accordingly, Aventinus continues, the Hungarians took possession of "both Dacias on this side and beyond" the Tisza east of the rivers Danube and Garam already in 893.[167] Indeed, the Hungarian chronicles unanimously state that the Székelys had already been present in the Carpathian Basin when the Hungarians moved in.[170] Kristó argues that Aventinus and the Hungarian historical tradition together point at an early occupation of the eastern territories of the Carpathian Basin by auxiliary troops of the Hungarian tribal confederation.[170]

The Annals of Fulda narrates under the year 894 that the Hungarians crossed the Danube into Pannonia where they "killed men and old women outright and carried off the young women alone with them like cattle to satisfy their lusts and reduced the whole" province "to desert".[171][172] Although the annalist writes of this Hungarian attack after the passage narrating Svatopluk I's death,[171] Györffy, Kristó,[173] Róna-Tas[174] and other historians suppose that the Hungarians invaded Pannonia in alliance with the Moravian monarch.[175] They argue that the "Legend of the White Horse" in the Hungarian chronicles preserved the memory of a treaty the Hungarians concluded with Svatopluk I according to pagan customs.[176] The legend narrates that the Hungarians purchased their future homeland in the Carpathian Basin from Svatopluk for a white horse harnessed with gilded saddle and reins.[173]

Then [Kusid] came to the leader of the region who reigned after Attila and whose name was Zuatapolug, and saluted him in the name of his people [...]. On hearing this, Zuatapolug rejoiced greatly, for he thought that they were peasant people who would come and till his land; and so he dismissed the messenger graciously. [...] Then by a common resolve [the Hungarians] despatched the same messenger again to the said leader and sent to him for his land a big horse with a golden saddle adorned with the gold of Arabia and a golden bridle. Seeing it, the leader rejoiced all the more, thinking that they were sending gifts of homage in return for land. When therefore the messenger asked of him land, grass and water, he replied with a smile, "In return for the gift let them have as much as they desire." [...] Then [the Hungarians] sent another messenger to the leader and this was the message which he delivered: "Arpad and his people say to you that you may no longer stay upon the land which they bought of you, for with the horse they bought your earth, with the bridle the grass, and with the saddle the water. And you, in your need and avarice, made to them a grant of land, grass and water." When this message was delivered to the leader, he said with a smile: "Let them kill the horse with a wooden mallet, and throw the bridle on the field, and throw the golden saddle into the water of the Danube." To which the messenger replied: "And what loss will that be to them, lord? If you kill the horse, you will give food for their dogs; if you throw the bridle on the field, their men will find the gold of the bridle when they mow the hay; if you throw the saddle into the Danube, their fishermen will lay out the gold of the saddle upon the bank and carry it home. If they have earth, grass and water, they have all."

Ismail Ibn Ahmed, the emir of Khorasan raided "the land of the Turks"[178] (the Karluks) in 893. Later he caused a new movement of peoples who one by one invaded the lands of their western neighbors in the Eurasian steppes.[179][180] Al-Masudi clearly connected the westward movement of the Pechenegs and the Hungarians to previous fights between the Karluks, Ouzes and Kimeks.[181] Porphyrogenitus writes of a joint attack by the Khazars and Ouzes that compelled the Pechenegs to cross the Volga River sometime between 893 and 902[182] (most probably around 894).[180]

Originally, the Pechenegs had their dwelling on the river [Volga] and likewise on the river [Ural] (…). But fifty years ago the so-called Uzes made common cause with the Chazars and joined battle with the Pechenegs and prevailed over them and expelled them from their country (…).

The relationship between Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire sharpened in 894, because Emperor Leo the Wise forced the Bulgarian merchants to leave Constantinople and settle in Thessaloniki.[184] Subsequently, Tzar Simeon I of Bulgaria invaded Byzantine territories[185] and defeated a small imperial troop.[186] The Byzantines approached the Hungarians to hire them to fight the Bulgarians.[185] Nicetas Sclerus, the Byzantine envoy, concluded a treaty with their leaders, Árpád and Kurszán (Kusan)[187] and Byzantine ships transferred Hungarian warriors across the Lower Danube.[185] The Hungarians invaded Bulgaria, forced Tzar Simeon to flee to the fortress of Dristra (now Silistra, Bulgaria) and plundered Preslav.[186] An interpolation in Porphyrogenitus's work states that the Hungarians had a prince named "Liountikas, son of Arpad"[136] at that time, which suggests that he was the commander of the army, but he might have been mentioned in the war context by chance.[188]

Simultaneously with the Hungarian attack from the north, the Byzantines invaded Bulgaria from the south. Tzar Simeon sent envoys to the Byzantine Empire to propose a truce. At the same time, he sent an embassy to the Pechenegs to incite them against the Hungarians.[186] He succeeded and the Pechenegs broke into Hungarian territories from the east, forcing the Hungarian warriors to withdraw from Bulgaria.[189] The Bulgarians, according to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, attacked and routed the Hungarians.[185][190]

The Pechenegs destroyed the Hungarians' dwelling places.[185] Those who survived the double attack left the Pontic steppes and crossed the Carpathians in search of a new homeland.[185] The memory of the destruction brought by the Pechenegs seems to have been preserved by the Hungarians.[191] The Hungarian name of the Pechenegs (besenyő) corresponds to the old Hungarian word for eagle (bese). Thus the 14th-century Hungarian chronicles' story of eagles compelling the Hungarians' ancestors to cross the Carpathians most probably refers to the Pechenegs' attack.[191]

The Hungarians were (…) driven from their home (…) by a neighboring people called the Petchenegs, because they were superior to them in strength and number and because (…) their own country was not sufficient to accommodate their swelling numbers. After they had been forced to flee by the violence of the Petchenegs, they said goodbye to their homeland and set out to look for lands where they could live and establish settlements.

[At] the invitation of Leo, the Christ-loving and glorious emperor [the Hungarians] crossed over and fought Symeon and totally defeated him, (…) and they went back to their own county. (…) But after Symeon (…) sent to the Pechenegs and made an agreement with them to attack and destroy [the Hungarians] And when [the latter] had gone off on a military expedition, the Pechenegs with Symeon came against [them] and completely destroyed their families and miserably expelled thence [those] who were guarding their country. When [the Hungarians] came back and found their country thus desolate and utterly ruined, they settled in the land where they live today (…).

Passing through the kingdom of the Bessi and the Cumani Albi and Susdalia and the city named Kyo, they crossed the mountains and came into a region where they saw innumerable eagles; and because of the eagles they could not stay in that place, for the eagles came down from the trees like flies and devoured both their herds and their horses. For God intended that they should go down more quickly into Hungary. During three months they made their descent from the mountains, and they came to the boundaries of the kingdom of Hungary, that is to Erdelw [...].

First phase (c. 895–899)

The date of the Hungarian invasion varies according to the source.[194] The earliest date (677) is preserved in the 14th-century versions of the "Hungarian Chronicle", while Anonymous supplies the latest date (902).[195] Contemporaneous sources suggest that the invasion followed the 894 Bulgarian-Byzantine war.[196] The route taken across the Carpathians is also contested.[197][2] Anonymous and Simon of Kéza have the invading Hungarians crossing the northeastern passes, while the Illuminated Chronicle writes of their arrival in Transylvania.[198]

Regino of Prüm states that the Hungarians "roamed the wildernesses of the Pannonians and the Avars and sought their daily food by hunting and fishing"[90] following their arrival in the Carpathian Basin.[13] Their advance towards the Danube seems to have stimulated Arnulf who was crowned emperor to entrust Braslav (the ruler of the region between the rivers Drava and Sava)[199] with the defense of all Pannonia in 896.[200] In 897 or 898 a civil war broke out between Mojmir II and Svatopluk II (two sons of the late Moravian ruler, Svatopluk I), in which Emperor Arnulf also intervened.[201][202][203] There is no mention of the Hungarians' activities in those years.[204]

The next event recorded in connection with the Hungarians is their raid against Italy in 899 and 900.[205] The letter of Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg and his suffragans suggests that Emperor Arnulf incited them to attack King Berengar I of Italy.[206] They routed the Italian troops on September 2 at the river Brenta[207] and plundered the region of Vercelli and Modena in the winter,[208] but the Doge of Venice, Pietro Tribuno defeated them at Venice on June 29, 900.[206] They returned from Italy when they learned of the death of Emperor Arnulf at the end of 899.[209]

According to Anonymous, the Hungarians fought with Menumorut before conquering Gelou's Transylvania.[210][211] Subsequently the Hungarians turned against Salan,[212] the ruler of the central territories, according to this narrative.[213] In contrast with Anonymous, Simon of Kéza writes of the Hungarians' fight with Svatopluk following their arrival.[2] According to the Illuminated Chronicle, the Hungarians "remained quietly in Erdelw and rested their herds"[214] there after their crossing because of an attack by eagles.[2]

The Hungarian chronicles preserved two separate lists of the Hungarians' leaders at the time of the Conquest.[215] Anonymous knows of Álmos, Előd, Künd, Ónd, Tas, Huba and Tétény,[216] while Simon of Kéza and the Illuminated Chronicle list Árpád, Szabolcs, Gyula, Örs, Künd, Lél and Vérbulcsú.[215][217] Contemporaraneous or nearly contemporaraneous sources make mention of Álmos (Constantine Porphyrogenitus), of Árpád (Continuation of the Chronicle by George the Monk and Constantine Porphyrogenitus), of Liountikas (Constantine Porphyrogenitus) and of Kurszán (Continuation of the Chronicle by George the Monk).[218]

According to the Illuminated Chronicle, Álmos, Árpád's father "could not enter Pannonia, for he was killed in Erdelw".[214][2] The episode implies that Álmos was the kende, the sacred ruler of the Hungarians, at the time of their destruction by the Pechenegs, which caused his sacrifice.[219] If his death was in fact the consequence of a ritual murder, his fate was similar to the Khazar khagans who were executed, according to Ibn Fadlan and al-Masudi, in case of disasters affecting their whole people.[2]

Second phase (900–902)

The emperor's death released the Hungarians from their alliance with East Francia.[208] On their way back from Italy they expanded their rule over Pannonia.[220] Furthermore, according to Liutprand of Cremona, the Hungarians "claimed for themselves the nation of the Moravians, which King Arnulf had subdued with the aid of their might"[221] at the coronation of Arnulf's son, Louis the Child in 900.[222] The Annals of Grado relates that the Hungarians defeated the Moravians after their withdrawal from Italy.[223] Thereafter the Hungarians and the Moravians made an alliance and jointly invaded Bavaria, according to Aventinus.[224] However, the contemporary Annals of Fulda only refers to Hungarians reaching the river Enns.[225]

One of the Hungarian contingents crossed the Danube and plundered the territories on the river's north bank, but Luitpold, Margrave of Bavaria gathered troops and routed them between Passau and Krems an der Donau[226] on November 20, 900.[224] He had a strong fortress erected against them on the Enns.[227] Nevertheless, the Hungarians became the masters of the Carpathian Basin by the occupation of Pannonia.[224] The Russian Primary Chronicle may also reflect the memory of this event[222] when relating how the Hungarians expelled the "Volokhi" who had earlier subjugated the Slavs' homeland in Pannonia.[228] These Volokhi, however, have also been associated either with the Romans or with the Vlachs (Romanians), for instance by Cross[229] and Spinei,[230] respectively.[22]

Over a long period the Slavs settled beside the Danube, where the Hungarian and Bulgarian lands now lie. From among these Slavs, parties scattered throughout the country and were known by appropriate names, according to the places where they settled. (...) The [Hungarians] passed by Kiev over the hill now called Hungarian and on arriving at the Dnieper, they pitched camp. They were nomads like the Polovcians. Coming out of the east, they struggled across the great mountains and began to fight against the neighboring [Volokhi][228] and Slavs. For the Slavs had settled there first, but the [Volokhi] had seized the territory of the Slavs. The [Hungarians] subsequently expelled the [Volokhi], took their land and settled among the Slavs, whom they reduced to submission. From that time the territory was called Hungarian.

King Louis the Child held a meeting at Regensburg in 901 to introduce further measures against the Hungarians.[227] Moravian envoys proposed a peace between Moravia and East Francia, because the Hungarians had in the meantime plundered their country.[227] A Hungarian army invading Carinthia was defeated[232] in April and Aventinus describes a defeat of the Hungarians by Margrave Luitpold at the river Fischa in the same year.[233]

Consolidation (902–907)

The date when Moravia ceased to exist is uncertain, because there is no clear evidence either on the "existence of Moravia as a state" after 902 (Spinei) or on its fall.[220] A short note in the Annales Alamannici refers to a "war with the Hungarians in Moravia" in 902, during which the "land (patria) succumbed", but this text is ambiguous.[234] Alternatively, the so-called Raffelstetten Customs Regulations mentions the "markets of the Moravians" around 905.[202] The Life of Saint Naum relates that the Hungarians occupied Moravia, adding that the Moravians who "were not captured by the Hungarians, ran to the Bulgars". Constantine Porphyrogenitus also connects the fall of Moravia to its occupation by the Hungarians.[20] The destruction of the early medieval urban centers and fortresses at Szepestamásfalva (Spišské Tomášovce), Dévény and other places in modern Slovakia is dated to the period around 900.[235]

After the death of (...) [Svatopluk I, his sons] remained at peace for a year and then strife and rebellion fell upon them and they made a civil war against one another and the [Hungarians] came and utterly ruined them and possessed their country, in which even now [the Hungarians] live. And those of the folk who were left were scattered and fled for refuge to the adjacent nations, to the Bulgarians and [Hungarians] and Croats and to the rest of the nations.

According to Anonymous, who does not write of Moravia, the Hungarians invaded the region of Nyitra (Nitra, Slovakia) and defeated and killed Zobor, the local Czech ruler, on Mount Zobor near his seat.[237] Thereafter, as Anonymous continues, the Hungarians first occupied Pannonia from the "Romans" and next battled with Glad and his army composed of Bulgarians, Romanians and Pechenegs from Banat.[115] Glad ceded few towns from his duchy.[238] Finally, Anonymous writes of a treaty between the Hungarians and Menumorut,[212] stipulating that the local ruler's daughter was to be given in marriage to Árpád's son, Zolta.[239] Macartney[240] argues that Anonymous's narration of both Menumorot and of Glad is basically a transcription of a much later report of the early 11th-century Achtum, Glad's alleged descendant.[241] In contrast, for instance, Madgearu maintains that Galad, Kladova, Gladeš and other place names recorded in Banat in the 14th century and 16th century attest to the memory of a local ruler named Glad.[242]

[The Hungarians] reached the region of Bega and stayed there for two weeks while they conquered all the inhabitants of that land from the Mures to the Timis River and they received their sons as hostages. Then, moving the army on, they came to the Timis River and encamped beside the ford of Foeni and when they sought to cross the Timis's flow, there came to oppose them Glad, (...) the prince of that country, with a great army of horsemen and foot soldiers, supported by Cumans, Bulgarians and Vlachs. (...) God with His grace went before the Hungarians, He gave them a great victory and their enemies fell before them as bundles of hay before reapers. In that battle two dukes of the Cumans and three kneses of the Bulgarians were slain and Glad, their duke escaped in flight but all his army, melting like wax before flame, was destroyed at the point of the sword. (...) Prince Glad, having fled, as we said above, for fear of the Hungarians, entered the castle of Kovin. (...) [He] sent to seek peace with [the Hungarians] and of his own will delivered up the castle with diverse gifts.

An important event following the conquest of the Carpathian Basin, the Bavarians' murder of Kurszán, was recorded by the longer version of the Annals of Saint Gall, the Annales Alamannici and the Annals of Einsiedeln.[244] The first places the event in 902, while the others date it to 904.[244][245] The three chronicles unanimously state that the Bavarians invited the Hungarian leader to a dinner on the pretext of negotiating a peace treaty and treacherously assassinated him.[246] Kristó and other Hungarian historians argue that the dual leadership over the Hungarians ended with Kurszán's death.[247][248]

The Hungarians invaded Italy using the so-called "Route of the Hungarians" (Strada Ungarorum) leading from Pannonia to Lombardy in 904.[249] They arrived as King Berengar I's allies[245] against his rival, King Louis of Provance. The Hungarians devastated the territories occupied earlier by King Louis along the river Po, which ensured Berengar's victory. The victorious monarch allowed the Hungarians to pillage all the towns that had earlier accepted his opponent's rule,[249] and agreed to pay a yearly tribute of about 375 kilograms (827 lb) of silver.[245]

The longer version of the Annals of Saint Gall reports that Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg fell, along with Bishops Uto of Freising and Zachary of Säben, in a "disastrous battle" fought against the Hungarians at Brezalauspurc on July 4, 907.[250] Other contemporary sources add that Margrave Luitpold of Bavaria and 19 Bavarian counts[245] also died in the battle.[250] Most historians (including Engel,[207] Makkai,[251] and Spinei) identify Brezalauspurc with Pressburg (Bratislava, Slovakia), but some researchers (for instance Boba and Bowlus) argue that it can refer to Mosaburg, Braslav's fortress on the Zala in Pannonia.[252][253] The Hungarians' victory hindered any attempts of eastward expansion by East Francia for the following decades[252] and opened the way for the Hungarians to freely plunder vast territories of that kingdom.[207]

Consequences

.jpg)

The Hungarians settled in the lowlands of the Carpathian Basin along the rivers Danube, Tisza and their tributaries,[254] where they could continue their semi-nomadic lifestyle.[255] As an immediate consequence, their arrival "drove a non-Slavic wedge between the West Slavs and South Slavs" (Fine).[189] Fine argues that the Hungarians' departure from the western regions of the Pontic steppes weakened their former allies, the Khazars, which contributed to the collapse of the Khazar Empire.[189]

The Hungarians left wide marches (the so-called gyepű) in the borderlands of their new homeland uninhabited for defensive purposes.[256] In this easternmost territory of the Carpathian Basin, the earliest graves attributed to Hungarian warriors—for instance, at Szék (Sic), Torda (Turda) and Vízakna (Ocna Sibiului)—are concentrated around the Transylvanian salt mines in the valley of the rivers Kis-Szamos (Someșul Mic) and Maros (Mureş).[257] All the same, warriors were also stationed in outposts east of the Carpathians, as suggested by 10th-century graves unearthed at Krylos, Przemyśl, Sudova Vyshnia, Grozeşti, Probota and at Tei.[258] The Hungarians' fear of their eastern neighbors, the Pechenegs, is demonstrated by Porphyrogenitus's report on the failure of a Byzantine envoy to persuade them to attack the Pechenegs.[259] The Hungarians clearly stated that they could not fight against the Pechenegs, because "their people are numerous and they are the devil's brats".[259][260]

Instead of attacking the Pechenegs and the Bulgarians in the east, the Hungarians made several raids in Western Europe.[251] For instance, they plundered Thuringia and Saxony in 908, Bavaria and Swabia in 909 and 910 and Swabia, Lorraine and West Francia in 912.[252] Although a Byzantine hagiography of Saint George refers to a joint attack of Pechenegs, "Moesians" and Hungarians against the Byzantine Empire in 917, its reliability is not established.[261] The Hungarians seem to have raided the Byzantine Empire for the first time in 943.[262] However, their defeat in the battle of Lechfeld in 955 "put an end to the raids in the West" (Kontler), while they stopped plundering the Byzantines following their defeat in the battle of Arkadiopolis in 970.[263]

The Hungarian leaders decided that their traditional lifestyle, partly based on plundering raids against sedentary peoples, could not be continued.[131] The defeats at the Lechfeld and Arkadiopolis accelerated the Hungarians' adoption of a sedentary way of life.[263] This process culminated in the coronation of the head of the Hungarians, Stephen the first king of Hungary in 1000 and 1001.[264]

Artistic representation

The most famous perpetuation of the events is the Arrival of the Hungarians or Feszty Panorama which is a large cyclorama (a circular panoramic painting) by Hungarian painter Árpád Feszty and his assistants. It was completed in 1894 for the 1000th anniversary of the event.[265] Since the 1100th anniversary of the event in 1995, the painting has been displayed in the Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park, Hungary. Mihály Munkácsy also depicted the event under the name of Conquest for the Hungarian Parliament Building in 1893.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristó 1996a, p. 191.

- ↑ Tóth 1999, note 2 on p. 23.

- ↑ Roman 2003, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2003, p. 650.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 53.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 55.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ Engel 2003, p. 652.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 56.

- ↑ Engel 2003, p. 653.

- 1 2 Engel 2003, p. 654.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 57.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 176.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, p. 16.

- 1 2 Madgearu 2005b, p. 91.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 185.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 61.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 193.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 62.

- 1 2 Madgearu 2005b, p. 52.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, p. 1.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, p. 24.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 58.

- ↑ Szakács 2006, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Buranbaeva & Mladineo 2011, p. 113.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, p. 20.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 350.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, p. 59.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 71.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 117–118., 134.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 37.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 17.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 139.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 39.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 55., 58.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 193.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 231.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 151.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 57–59.

- 1 2 3 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Kristó 1996b, p. 95.

- ↑ Kiss 1983, pp. 187., 190., 233., 408., 481., 532., 599., 643.

- ↑ Kiss 1983, pp. 80., 108., 661., 712.

- 1 2 Makkai 1994.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996b, p. 96.

- ↑ Kiss 1983, pp. 166–167., 331., 465., 697.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 110–111.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, pp. 44, 57.

- ↑ Hajdú 2004, p. 243.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996b, p. 98.

- ↑ Kristó 1996b, p. 96., 98.

- ↑ Kiss 1983, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 39.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 10.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 Spinei 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ The Annals of St-Bertin (year 862), p. 102

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 237.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 338.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 148., 156.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 38), p. 173.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), p. 175.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 Spinei 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 124.

- 1 2 Makkai 1994, p. 10.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 1.), p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Spinei 2003, p. 51.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 329.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 237–238.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 34., 37.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 69–72.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 101–104.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 343., 347.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 42.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, pp. 343., 353.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 20.

- 1 2 The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (year 889), p. 205.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 19.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 358.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 136.

- ↑ The Taktika of Leo VI (18.47–50), pp. 455–457.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 262.

- ↑ Makkai 1994, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 2.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Makkai 1994, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Szőke 2003, p. 314.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 57–58.

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 57.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 264.

- ↑ Pohl 1998, p. 19.

- 1 2 Olajos 2001, p. 55.

- 1 2 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 285-286.

- ↑ Kristó 1996b, p. 97-98.

- 1 2 3 Béla Miklós Szőke (17 April 2013). "A Kárpát-medence a Karoling-korban és a magyar honfoglalás (Tudomány és hagyományőrzés konferencia)" (PDF) (in Hungarian). MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 8.

- 1 2 Macartney 1953, pp. 64–65, 70.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 9.), p. 27.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, p. 45.

- 1 2 Georgescu 1991, p. 15.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 11.), p. 33.

- ↑ Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 2.23), pp. 73-75.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, p. 103.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, pp. 70, 80.

- ↑ Pop 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 72–73.

- 1 2 3 4 Róna-Tas 1999, p. 243.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 133.

- ↑ Szőke 2003, p. 315.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 125.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 202.

- ↑ The Annals of Fulda (year 884), p. 110.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 208–213.

- 1 2 Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Curta 2006, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 3 Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), p. 177.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 180.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 181.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 127.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 130.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 4.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Royal Frankish Annals (year 824), p. 116.

- ↑ Curta 2006, pp. 157–159.

- ↑ Royal Frankish Annals (year 827), p. 122.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 107.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 158.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 159.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 118.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 224–225., 229.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 229.

- ↑ The Annals of Fulda (year 892), p. 124.

- 1 2 Fine 1991, p. 11.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 35.), p. 77.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 24.), p. 59.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, p. 115.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 148.

- 1 2 Tóth 1998, p. 169.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 169., 230–231.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 170.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 170., 226., 234.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 336.

- 1 2 3 Kristó 1996a, p. 175.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 241.

- ↑ Liudprand of Cremona: Retribution (1.13), p. 56.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996b, p. 107.

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 240.

- ↑ The Annals of Fulda (year 894), p. 129.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 177.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 332.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 150.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 28), p. 99.

- ↑ The History of al-Tabari (38:2138), p. 11.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 178.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 182.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 37), p. 167.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Curta 2006, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 Fine 1991, p. 138.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 183.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 Fine 1991, p. 139.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 12.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 188.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (year 889), pp. 204–205.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 26), p. 98.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 189.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 191.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ Spinei 2009, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 214., 241–242.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 195.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 243.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, p. 23.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 197.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 197–198.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2003, p. 13.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 68.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 244, 246.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Pop 1996, pp. 131-136.

- 1 2 Madgearu 2005b, p. 22.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 59.

- 1 2 The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 28), p. 98.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 31.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 6.), p. 19.

- ↑ Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 2.27-33.), pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Tóth 1998, p. 116., 121., 125.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, pp. 191–192.

- 1 2 Spinei 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Liudprand of Cremona: Retribution (2.2), p. 75.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 200.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 246.

- 1 2 3 Kristó 1996a, p. 199.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 247.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 247–248.

- 1 2 3 Bowlus 1994, p. 248.

- 1 2 Madgearu 2005b, p. 51.

- ↑ Russian Primary Chronicle (1953, note 29 on p. 235)

- ↑ Spinei 2009, p. 73.

- ↑ The Russian Primary Chronicle (Introduction and years 888–898), pp. 52–53., 62.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 248–250.

- ↑ Kristó 1996b, p. 142.

- ↑ Kristó 1996b, p. 141.

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 109–111.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 41), p. 181.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 257.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 22., 33., 39.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 62.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, p. 25.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, pp. 71., 79.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005b, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 44.), p. 97.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996a, p. 201.

- 1 2 3 4 Spinei 2003, p. 70.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 250.

- ↑ Kristó 1996a, p. 203.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 251.

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 254.

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 258.

- 1 2 Makkai 1994, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Spinei 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 259–265.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 45.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 44.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005a, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 118.

- 1 2 Kristó 1996b, p. 145.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 8), p. 57

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 77.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 47.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 84.

- ↑ "The Puszta and Lake Tisza". Tourism portal of Hungary. 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

References

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation by Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- Liudprand of Cremona: Retribution (2007). In: The Complete Works of Liudprand of Cremona (Translated by Paolo Squatriti); The Catholic University of Press; ISBN 978-0-8132-1506-8.

- Royal Frankish Annals (1972). In: Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories (Translated by Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers); The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 0-472-06186-0.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- The Annals of Fulda (Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II) (Translated and annotated by Timothy Reuter) (1992). Manchaster University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3458-2.

- The Annals of St-Bertin (Ninth-Century Histories, Volume I) (Translated and annotated by Janet L. Nelson) (1991). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3426-8.

- The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (2009). In: History and Politics in Late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe: The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm and Adalbert of Magdeburg (Translated and annotated by Simon MacLean); Manchester University Press; ISBN 978-0-7190-7135-5.

- The History of al-Tabarī, Volume XXXVIII: The Return of the Caliphate to Baghdad (Translated by Franz Rosenthal) (1985). State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-876-4.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

- The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text (Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor) (1953). Medieval Academy of America. ISBN 978-0-915651-32-0.

- The Taktika of Leo VI (Text, translation, and commentary by George T. Dennis) (2010). Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-359-3.

Secondary sources

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- Bartl, Július (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1994). Franks, Moravians and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788–907. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3276-3.

- Buranbaeva, Oksana; Mladineo, Vanja (2011). Culture and Customs of Hungary. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-38369-4.

- Curta, Florin (2001). "Transylvania around A.D 1000". In Urbańczyk, Przemyslaw. Europe around the Year 1000. Wydawn. pp. 141–165. ISBN 83-7181-211-6.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Engel, Pál (2003). "A honfoglalás és a Fehérló-monda "igaz története" [The "True Story" of the Hungarian Conquest and the Legend of the White Horse]". In Csukovits, Enikő. Engel Pál: Honor, vár, ispánság: Válogatott tanulmányok [Engel, Pál: Honor, Castle, County: Selected Studies] (in Hungarian). Osiris Kiadó. pp. 649–660. ISBN 963-389-392-5.

- Fine, John V. A (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Hajdú, Mihály (2004). "The Hungarian language". In Nanovfszky, György; Rubovszky, Éva; Klima, László; et al. The Finno-Ugric World. Teleki László Foundation & Hungarian National Organisation of the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples. pp. 235–246. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

- Kiss, Lajos (1983). Földrajzi nevek etimológiai szótára [Etymological Dictionary of Geographical Names] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-3346-4.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kristó, Gyula (1996a). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szegedi Középkorász Muhely. ISBN 963-482-113-8.

- Kristó, Gyula (1996b). Magyar honfoglalás, honfoglaló magyarok [Hungarian Land-taking, Land-taking Hungarians] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Muhely. ISBN 963-09-3836-7.

- Macartney, C. A. (1953). The Medieval Hungarian Historians: A Critical & Analytical Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08051-4.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005a). "Chapter Three: Salt Trade and Warfare: The Rise of Romanian-Slavic Military Organization in Early Medieval Transylvania". In Curta, Florin. East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The University of Michigan Press. pp. 103–120. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005b). The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum: Truth and Fiction. Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 973-7784-01-4.

- Makkai, László (1994). "Hungary before the Hungarian conquest; The Hungarians' prehistory, their conquest of Hungary and their raids to the West to 955". In Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor. A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

- Makkai, László (2001). Transylvania in the Medieval Hungarian Kingdom (896–1526), History of Transylvania, Volume I. Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

- Olajos, Teréz (2001). "Az avar továbbélés kérdéséről: a 9. századi avar történelem görög és latin nyelvű forrásai [=On the survival of the Avars: Greek and Latin sources of the 9th-century of the Avar history]" (PDF). Tiszatáj (in Hungarian) (Szeged (HU): Tiszatáj Alapítvány) 55 (11): 50–56. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- Pohl, Walter (1998). "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies". In Little, Lester K.; Rosenwein, Barbara. Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings. Blackwell Publishers. pp. 15–24. ISBN 1-57718-008-9.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century: The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State. Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundaţia Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-037-7.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2013). "De manibus Valachorum scismaticorum...": Romanians and Power in the Mediaeval Kingdom of Hungary: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-64866-7.

- Roman, Eric (2003). Austria–Hungary & the Successor States: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4537-2.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History (Translated by Nicholas Bodoczky). CEU Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1.

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century (Translated by Dana Badulescu). ISBN 973-85894-5-2.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Szakács, Béla Zsolt (2006). "Between Chronicle and Legend: Image Cycles of St Ladislaus in Fourteenth-Century Hungarian Manuscripts". In Kooper, Erik. The Medieval Chronicle, IV. Rodopi. pp. 149–176. ISBN 978-90-420-2088-7.

- Szőke, Béla Miklós (2003). "A Karoling-kor (811–896) [Carolingian Age (811–896)]". In Visy, Zsolt; Nagy, Mihály; B. Kiss, Zsuzsa. Magyar régészet az ezredfordulón [Hungarian Archaeology at the Turn of the Millennium] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Nemzeti Kulturális Örökség Minisztériuma. pp. 312–317. ISBN 978-963-86291-7-3.

- Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levédiától a Kárpát-medencéig [From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Muhely. ISBN 963-482-175-8.

- Tóth, Sándor László (1999). "The Territories of the Hungarian Tribal Federation around 950 (Some Observations on ConstantineVII's "Tourkia")". In Prinzing, Günter; Salamon, Maciej. Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa, 950–1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX International Congress of Byzantine Studies,Copenhagen 1996 [Byzantium and East Central Europe, 950–1453: Contributions to the Round-table Discussions of the 19th International Congress of Byzantine Studies,Copenhagen 1996]. Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 23–34. ISBN 3-447-04146-3.

Further reading

- Fodor, István (1982). In Search of a New Homeland: The Prehistory of the Hungarian People and the Conquest. Corvina Kiadó. ISBN 963-1311-260.

- Horedt, Kurt (1986). Siebenbürgen im Frühmittelalter [Transylvania in the Early Middle Ages] (in German). Habelt. ISBN 3-7749-2195-4.

- Nägler, Thomas (2005). "Transylvania between 900 and 1300". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas. The History of Transylvania, Vol. I. (Until 1541). Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 199–231. ISBN 973-7784-00-6.