Hungarian irredentism

Hungarian irredentism is a broad umbrella term consisting of irredentist and pan-nationalist political ideas. The idea is associated with Hungarian revisionism. Its main goal is to restore the pre-WW1 borders of the Kingdom of Hungary.

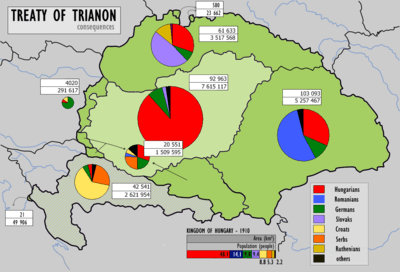

After World War II, Hungarian leaders shied away from this policy, and today it persists as the stated political goal of more marginal factions. The Treaty of Trianon defined the borders of the new independent Hungary and, compared against the claims of the pre-war Kingdom, new Hungary had approximately 72% less land stake and about two-thirds less inhabitants, almost 3 million of these being of Hungarian ethnicity.[1][2] However, most of the inhabitants of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary were not ethnic Hungarians. Following the treaty's instatement, Hungarian leaders became inclined towards revoking some of its terms. This political aim gained greater attention and was a serious national concern up through the second World War.[3]

The arguments of Hungarian revisionists (as advocates for restoring a Greater Hungary called themselves) for their goal were: the presence of Hungarian majority areas in the neighboring countries, perceived historical traditions of the Kingdom of Hungary, or the perceived geographical unity and economic symbiosis of the region within the Carpathian Basin, although some Hungarian revisionists preferred to regain only ethnically Hungarian majority areas surrounding Hungary.

Hungary, supported by the Axis Powers, was partially successful in gaining some (primarily ethnic Hungarian) regions of the former Kingdom in the Vienna Awards of 1938 and 1940, and through military campaign gained regions of Carpathian Ruthenia in 1939 and (ethnically mixed) Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje, and Prekmurje in 1941 (Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories). Following the close of World War II, the borders of Hungary as defined by the Treaty of Trianon were restored, except for three Hungarian villages that were transferred to Czechoslovakia. These villages are today administratively a part of Bratislava. Historical revisionism was often used by both proponents and opponents of Greater Hungary. Contemporarily, some Hungarians still express period nostalgia for the historical Kingdom of Hungary, but territorial reclamation is a fringe political aim.

History

Background

The independent Kingdom of Hungary was established in 1000 AD, and remained a power in Central Europe until Ottoman Empire conquered its central part in 1526 following the Battle of Mohács. After the battle, the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary was divided into three portions: in the west and north, Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary retained its existence under Habsburg rule; the Ottomans controlled the south-central parts of former Kingdom of Hungary; while in the east, the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (later the Principality of Transylvania) was formed as a semi-independent entity under Ottoman suzerainty. Between 1699 and 1718, the Habsburg Monarchy conquered all the Ottoman territories that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before 1526, and incorporated some of these areas into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.

For few centuries, rulers such as Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (15th century) had maintained a relatively cosmopolitan kingdom. Because this identity existed for few centuries, modern Hungarian culture includes significant elements from places which were part of the Kingdom of Hungary in various parts of its history. Also, a considerable number of the figures who are today considered important in Hungarian culture were born in what are - since 1918 - parts of Romania, Slovakia, Ukraine, Serbia and Austria (see List of Hungarians who were born outside present-day Hungary). Names of Hungarian dishes, common surnames, proverbs, sayings, folk songs etc. also refer to these rich cultural ties. After the Ottoman conquest in the Kingdom of Hungary, the ethnic structure of the kingdom started to become more multi-ethnic because of immigration to the sparsely populated areas. After 1867, the non-Hungarian ethnic groups were subject to assimilation and Magyarization.

After a suppressed uprising in 1848-1849, the Kingdom of Hungary and its diet were dissolved, and territory of the Kingdom of Hungary was divided into 5 districts, which were Pest & Ofen, Ödenburg, Preßburg, Kaschau and Großwardein, directly controlled from Vienna while Croatia, Slavonia, and the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar were separated from the Kingdom of Hungary between 1849-1860. This new centralized rule, however, failed to provide stability, and in the wake of military defeats the Austrian Empire was transformed into Austria-Hungary with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, by which Kingdom of Hungary became one of two constituent entities of the new dual monarchy with self-rule in its internal affairs.

Division of the Kingdom of Hungary into five territories was ended on April 19, 1860, Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar was dissolved on December 27, 1860, Murinsel regained from Croatia on January 27, 1861. After the formation of the dual monarchy, Croatia and Slavonia were merged into Croatia-Slavonia, who compromised with the Kingdom of Hungary on November 17, 1868; Transylvania reunited with the Kingdom of Hungary on December 6, in 1860. Fiume passed to the Kingdom of Hungary on July 28, 1870. Finally, the Military borderlands is incorporated into Croatia-Slavonia within the Kingdom of Hungary in 1882.

This was followed by a period of backlash against the long-standing Austro-German cultural influence in the Kingdom of Hungary, which included policies of Magyarization of non-Hungarian nationalities. Among the most notable policies was the promotion of the Hungarian language as the country's official language (replacing Latin and German); however, this was often at the expense of Slavic languages and the Romanian language. The new government of autonomous Kingdom of Hungary took the stance that Kingdom of Hungary should be a Hungarian nation state, and that all other peoples living in the Kingdom of Hungary—Germans, Jews, Romanians, Slovaks, Ruthenes, Serbs, and other ethnicities—should be assimilated. (The Croats were to some extent an exception to this, as they had a fair degree of self-government within Croatia-Slavonia, a dependent kingdom within the Kingdom of Hungary.) Most of the increase of Hungarians came at the expense of the Germans and Jews, who were scattered in small communities throughout the kingdom and proved most willing to assimilate and become Hungarians. The Romanians and Slavic peoples in the Kingdom of Hungary, on the other hand, who were largely peasant peoples, proved much more resistant to the government's efforts.

World War I

The peace treaties signed after the First World War redefined the national borders of Europe. The dissolution of Austria-Hungary, after its defeat in the First World War, gave an opportunity for the subject nationalities of the old Monarchy to all form their own nation states (However, most of the resulting states nevertheless became multiethnic states comprising several nationalities). The Treaty of Trianon of 1920 defined borders for the new Hungarian state: in the north, the Slovak and Ruthene areas, including Hungarian majority areas became part of the new state of Czechoslovakia. Transylvania and most of the Banat became part of Romania, while Croatia-Slavonia and the other southern areas became part of the new state of Yugoslavia.

Post-Trianon Hungary had about half of the population of the former Kingdom. The population of the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary that were not assigned to the post-Trianon Hungary had, in total, non-Hungarian majority, although they included a sizable proportion of ethnic Hungarians and Hungarian majority areas. According to Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi the ethnic composition in 1910

| Region | Hungarians | Germans | Romanians | Serbs | Croats | Ukrainians (Ruthenians) | Slovaks | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transylvania[4] | 31.7% | 10.5% | 54.0% | 0.9% | 0.6% | Hungarians concentrated in Székely Land (Hungarian majority). | ||

| Vojvodina[5] | 28.1% | 21.4% | 33.8% | 6.0% | 0.9% | 3.7% | ||

| Transcarpathia[6] | 30.6% | 10.6% | 54.5% | 1.0% | 1.0% Slovaks and Czechs | |||

| Slovakia[7] | 30.2% | 6.8% | 3.5% | 57.9% | with Hungarians concentrated in the south, which has a Hungarian majority today. | |||

| Burgenland[8] | 9.0% | 74.4% | 15% | |||||

| Croatia-Slavonia[9] | 4% | 5% | 25% | 63% |

Trianon thus defined Hungary's new borders in a way that made ethnic Hungarians the overwhelmingly absolute majority in the country. Almost 3 million ethnic Hungarians remained outside the borders of post-Trianon Hungary.[1] A considerable number of non-Hungarian nationalities remained within the new borders of Hungary, the largest of which were Germans (Schwabs) with 550,062 people (6.9%).

Aftermath

After the Treaty of Trianon, a political concept known as Hungarian revisionism became popular in Hungary. The Treaty of Trianon was an injury for the Hungarian people, and Hungarian revisionists have created a nationalistic ideology with the political goal of the restoration of borders of historical pre-Trianon Kingdom of Hungary.

The justification for this aim usually followed the fact that two-thirds of the country's area was taken by the neighboring countries with approximately 3 million[1] Hungarians living in these territories. Several municipalities that had purely ethnic Hungarian population were excluded from post-Trianon Hungary, which had borders designed to cut most economic regions (Szeged, Pécs, Debrecen etc.) half, and keep railways on the other side.

Near realization

Hungary's government allied itself with Nazi Germany during World War II in exchange for assurances that Greater Hungary's borders would be restored. This goal was partially achieved when Hungary reannexed territories from Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia at the outset of the war. These annexations were affirmed under the Munich Agreement (1938), two Vienna Awards (1938 and 1940), and aggression against Yugoslavia (1941), the latter achieved one week after the German army had already invaded Yugoslavia.

The percentage of Hungarian speakers was 84% in southern Czechoslovakia and 15% in the Sub-Carpathian Rus.

The population of Northern Transylvania, according to the Hungarian census from 1941 counted 53.5% Hungarians and 39.1% Romanians.[10]

The Yugoslav territory occupied by Hungary (including Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje and Prekmurje) had approximately one million inhabitants, including 543,000 Yugoslavs (Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), 301,000 Hungarians, 197,000 Germans, 40,000 Slovaks, 15,000 Rusyns, and 15,000 Jews.[11] In Bačka region only, the 1931 census put the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian at 34.2%, while one of interpretations of later Hungarian census from 1941 states that, 45,4% or 47,2% declared themselves to be Hungarian native speakers or ethnic Hungarians [10] (this interpretation is provided by authors Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi. The 1941 census, however, did not recorded ethnicity of the people, but only mother/native tongue ). Population of entire Bačka numbered 789,705 inhabitants in 1941. This means that from the beginning of the occupation, the number of Hungarian speakers in Bačka increased by 48,550, while the number of Serbian speakers decreased by 75,166.[12]

The establishment of Hungarian rule met with insurgency on part of the non-Hungarian population in some places and retaliation of the Hungarian forces was labelled war crimes such as Ip and other localities in Northern Transylvania (directed against Romanians) or Bačka, where Hungarian military between 1941 and 1944 deported or killed 19,573 civilians,[13] mainly Serbs and Jews, but also Hungarians who did not collaborate with the new authorities. About 56,000 people were also expelled from Bačka.[12]

The Jewish population of Hungary and the areas it occupied were partly diminished as part of the Holocaust[14] against the wishes of the Hungarian community. Tens of thousands of Romanians fled from Hungarian-ruled Northern Transylvania, and vice versa. After the war the areas were returned to neighboring countries and Hungary's territory was slightly further reduced by ceding three villages south of Bratislava to Slovakia. The reoccupying states exercised reveng on Hungarian civilians, both in Yugoslavia by Yugoslav partisans (the exact number of ethnic Hungarians killed by Yugoslav partisans is not clearly established and estimates range from 4,000 to 40,000; 20,000 is often regarded as most probable[15]), and in Transylvania by the Maniu Guard towards the end of World War II.

Modern era

The following table lists areas with Hungarian population in neighboring countries today:

| |

|

|

|

| parts of Transylvania (mainly Harghita, Covasna and part of Mureş county, Central Romania), see: Hungarians in Romania |

1,227,623 (6.5%)[16] in Romania 1,216,666 (17.9%) in Transylvania |

Târgu Mureș Cluj-Napoca |

Székely Land (which would have an area of 13,000 km2[17] and a population of 809,000 people of which 75.65% Hungarians) |

| parts of Vojvodina in northern Serbia, see: Hungarians in Vojvodina |

293,299 (3.91%) in Serbia 290,207 (14.28%) in Vojvodina |

Subotica | Hungarian Regional Autonomy (which would have an area of 3,813 km2 and a population of 340,007 people of which 52.10% Hungarians and 41.11% South Slavs) |

| parts of southern Slovakia, see: Hungarians in Slovakia |

458,467 (8.5%) | Komárno | |

| parts of Zakarpattia Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, see: Hungarians in Ukraine |

156,566 (0.3%) in Ukraine 151,533 (12.09%) in Transcarpathia |

Berehove | |

During the Communist era, Marxist–Leninist ideology and Stalin's theory on nationalities considered nationalism to be a malady of a bourgeois capitalism. In Hungary, the minorities' question disappeared from the political agenda. Communist hegemony guaranteed a facade of inter-ethnic peace while failing to secure a lasting accommodation of minority interests in unitary states.

The fall of Communism aroused the expectations of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries and left Hungary unprepared to deal with the issue. Hungarian politicians campaigned to formalize the rights of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries, thus causing anxiety in the region. They secured agreements on the necessity for guaranteeing collective rights and formed new Hungarian minority organizations to promote cultural rights and political participation. In Romania, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia (now Serbia), former Communists secured popular legitimacy by accommodating nationalist tendencies that were hostile to minority rights.

The latest controversy caused by the government of Viktor Orbán is when Hungary took the presidency over the EU in 2011[19] when the "historical timeline" features was presented - among other cultural, historical and scientific symbols or images of Hungary - an 1848 map of Greater Hungary, when Budapest ruled over large swathes of its neighbors.[20][21]

Hungary

The campaign materials of Jobbik contain map of the pre-1920 Greater Hungary.[22]

Slovakia

Under great pressure from the EU and NATO, Hungary signed a bilateral state treaty with Slovakia on Good Neighborly Relations and Friendly Cooperation in March 1995, aimed at resolving disputes concerning borders and minority rights. Its vague language, though, allows rival interpretations. One cause of conflict was the COE's Recommendation 1201 which stipulates the creation of autonomous self-government based on ethnic principles in areas where ethnic minorities represent a majority of the population.

The Hungarian Prime Minister insisted that the treaty protected the Hungarian minority as a "community". Slovakia accepted the 1201 Recommendation in the treaty, but denounced the concept of collective rights of minorities and political autonomy as "unacceptable and destabilizing". Slovakia finally ratified the treaty in March 1996 after the government attached a unilateral declaration that the accord would not provide for collective autonomy for Hungarians. The Hungarian government therefore refused to recognize the validity of the declaration.

Romania

After World War II, a Hungarian Autonomous Region was created in Transylvania, which encompassed most of the land inhabited by the Székelys. This region lasted until 1964 when the administrative reform divided Romania into the current counties. From 1947 until the 1989 Romanian Revolution and the death of Nicolae Ceauşescu, a systematic Romanianization of Hungarians took place, with several discriminatory provisions, denying them their cultural identity. This tendency started to abate after 1989, the question of Székely autonomy remains a sensitive issue.

On 16 September 1996, after five years of negotiations, Hungary and Romania also signed a bilateral treaty, which had been stalled over the nature and extent of minority protection that Bucharest should grant to Hungarian citizens. Hungary dropped its demands for autonomy for ethnic minorities; in exchange, Romania accepted a reference to Recommendation 1201 in the treaty, but with a joint interpretive declaration that guarantees individual rights, but excludes collective rights and territorial autonomy based on ethnic criteria. These concessions were made in large measure because both countries recognized the need to improve good neighborly relations as a prerequisite for NATO membership.

Vojvodina, Serbia

There are five main ethnic Hungarian political parties in Vojvodina:

- Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by István Pásztor

- Democratic Community of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by Áron Csonka

- Democratic Party of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by András Ágoston

- Civic Alliance of Hungarians, led by László Rác Szabó

- Movement of Hungarian Hope, led by Bálint László

These parties are advocating the establishment of the territorial autonomy for Hungarians in the northern part of Vojvodina, which would include the municipalities with Hungarian majority (See Hungarian Regional Autonomy for details).

Ukraine

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Fenyvesi, Anna (2005). Hungarian language contact outside Hungary: studies on Hungarian as a minority language. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 90-272-1858-7. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ "Treaty of Trianon". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "HUNGARY". Hungarian Online Resources (Magyar Online Forrás). Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 14. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transylvania (1880-1992)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 21. Ethnic structure of the population of the present territory of Vojvodina (1880-1991)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 11. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transcarpathia (1880..1989)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 7. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Slovakia (1880-1991)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 25. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Burgenland (1880-1991)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Hugh (1945). Eastern Europe Between the Wars, 1918–1941 (3rd ed.). CUP Archive. p. 434. ISBN 1-00-128478-X.

- 1 2 Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 116-153

- ↑ Peter Rokai - Zoltan Đere - Tibor Pal - Aleksandar Kasaš, Istorija Mađara, Beograd, 2002.

- 1 2 Zvonimir Golubović, Racija u Južnoj Bačkoj, 1942. godine, Novi Sad, 1991.

- ↑ Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.

- ↑ Night by Elie Wiesel

- ↑ Dimitrije Boarov, Politička istorija Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 2001.

- ↑ "Final 2011 Census Result" (PDF). Final 2011 Census Result. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ "The Szeklers and their struggle for autonomy". Szekler National Council. 21 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Sebők László's ethnic map of Central and Southeastern Europe

- ↑ "(Home page)". Hungarian Presidency of The Council Of The European Union. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "Hungary in EU presidency 'history' carpet row". BBC. 2011-01-14. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑ "Hungary in EU presidency 'history' carpet row". Bucharest Herald. 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- ↑

Further reading

- Dupcsik, Csaba; Repárszky, Ildikó (2001). Történelem IV. XX. század (in Hungarian). Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó. ISBN 978-9631628142.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||