House of Bourbon

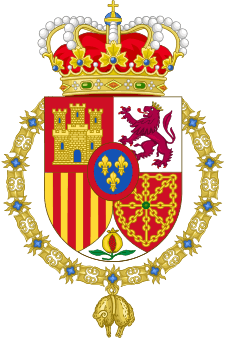

| House of Bourbon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | France, Italy, Navarre, Spain, Luxembourg |

| Parent house | Capetian Dynasty |

| Titles | |

| Founded | 1268 |

| Founder | Robert, Count of Clermont, the sixth son of King Louis IX of France, married Beatrix of Bourbon |

| Final ruler |

France and Navarre: Charles X (1824-1830) Of the French: Louis-Philippe I (1830–1848) Parma: Roberto I (1854–1859) Two Sicilies: Francis II (1859–1861) |

| Current head | Louis Alphonse (Louis XX) |

| Deposition |

France and Navarre: 1830: July Revolution 1859: Annexation by Kingdom of Sardinia Two Sicilies: 1861: Italian unification |

| Ethnicity | French, Spanish (Basque and Catalan), Italian (in Parma and the Two Sicilies), Luxembourger |

| Cadet branches | |

The House of Bourbon (English /ˈbɔːrbən/; French: [buʁˈbɔ̃]) is a European royal house of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty (/kəˈpiːʃⁱən/). Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Bourbon dynasty also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma. Spain and Luxembourg currently have Bourbon monarchs.

The royal Bourbons originated in 1268, when the heiress of the lordship of Bourbon married a younger son of King Louis IX.[1] The house continued for three centuries as a cadet branch, while more senior Capetians ruled France, until Henry IV became the first Bourbon king of France in 1589.[1] Bourbon monarchs then unified France with the small kingdom of Navarre, which Henry's father had acquired by marriage in 1555, and ruled until the 1792 overthrow of the monarchy during the French Revolution. Restored briefly in 1814 and definitively in 1815 after the fall of the First French Empire, the senior line of the Bourbons was finally overthrown in the July Revolution of 1830. A cadet Bourbon branch, the House of Orléans, then ruled for 18 years (1830–1848), until it too was overthrown.

The Princes de Condé were a cadet branch of the Bourbons descended from an uncle of Henry IV, and the Princes de Conti were a cadet branch of the Condé. Both houses were prominent in French affairs, even during exile in the French revolution, until their respective extinctions in 1830 and 1814.

When the Bourbons inherited the strongest claim to the Spanish throne, the claim was passed to a cadet Bourbon prince, a grandson of Louis XIV of France, who became Philip V of Spain.[1] Permanent separation of the French and Spanish thrones was secured when France and Spain ratified Philip's renunciation, for himself and his descendants, of the French throne in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1714, and similar arrangements later kept the Spanish throne separate from those of the Two Sicilies and Parma. The Spanish House of Bourbon (rendered in Spanish as Borbón [borˈβon]) has been overthrown and restored several times, reigning 1700–1808, 1813–1868, 1875–1931, and since 1975. Bourbons ruled in Naples from 1734–1806 and in Sicily from 1734–1816, and in a unified Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from 1816–1860. They also ruled in Parma from 1731–1735, 1748–1802 and 1847–1859.

Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg married a cadet of the Parmese line and thus her successors, who have ruled Luxembourg since her abdication in 1964, have also been members of the House of Bourbon. Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, regent for her father, Pedro II of the Empire of Brazil, married a cadet of the Orléans line and thus their descendants, known as the Orléans-Braganza, were in the line of succession to the Brazilian throne and expected to ascend its throne had the monarchy not been abolished by revolution in 1889.

All legitimate, living members of the House of Bourbon, including its cadet branches, are direct agnatic descendants of Henry IV.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)   | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| France portal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Origins

The pre-Capetian House of Bourbon was a noble family, dating at least from the beginning of the 13th century, when the estate of Bourbon was ruled by the Sire de Bourbon who was a vassal of the King of France. The term House of Bourbon ("Maison de Bourbon") is sometimes used to refer to this first house and the House of Bourbon-Dampierre, the second family to rule the seigneury.

In 1268, Robert, Count of Clermont, sixth son of King Louis IX of France, married Beatrix of Bourbon, heiress to the lordship of Bourbon and member of the House of Bourbon-Dampierre.[1] Their son Louis was made Duke of Bourbon in 1327. His descendant, the Constable of France Charles de Bourbon, was the last of the senior Bourbon line when he died in 1527. Because he chose to fight under the banner of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and lived in exile from France, his title was discontinued after his death.

The remaining line of Bourbons henceforth descended from James I, Count of La Marche, the younger son of Louis I, Duke of Bourbon.[1] With the death of his grandson James II, Count of La Marche in 1438, the senior line of the Count of La Marche became extinct. All future Bourbons would descend from James II's younger brother, Louis, who became the Count of Vendôme through his mother's inheritance.[1] While the most senior branch of the family, the House of Valois, continued to occupy the throne of France, at the death of Charles IV, Duke of Alençon in 1525, all of the princes of the blood royal were Bourbons.

In 1514, Charles, Count of Vendôme had his title raised to Duke of Vendôme. His son Antoine became King of Navarre, on the northern side of the Pyrenees, by marriage in 1555.[1] Two of Antoine's younger brothers were Cardinal Archbishop Charles de Bourbon and the French and Huguenot general Louis de Bourbon, 1st Prince of Condé. Louis' male-line, the Princes de Condé, survived until 1830. Finally, in 1589, the House of Valois died out and Antoine's son Henry III of Navarre became Henry IV of France.[1]

List of Bourbons

.svg.png) Dukes of Bourbon |  |  |  | .svg.png) | .svg.png) |

Bourbon branches

- House of Clermont, later called House of Bourbon

- House of the Dukes of Bourbon (extinct 1521)

- House of Bourbon-Lavedan (illegitimate), extinct 1744

- House of Bourbon-Busset (illegitimate)

- House of Bourbon-Roussillon (illegitimate), extinct 1510

- House of Bourbon-Montpensier, Counts of Montpensier (extinct 1527)

- House of Bourbon-La Marche (extinct 1438)

- House of Bourbon-Vendôme

- House of Bourbon, Kings of France

- House of Artois (extinct 1883)

- House of Bourbon, Kings of Spain

- House of Bourbon-Maine (illegitimate), extinct 1775

- House of Bourbon-Penthièvre (illegitimate), extinct 1793

- House of Orléans

- House of Bourbon-Vendôme (illegitimate), extinct 1727

- House of Bourbon-Condé (extinct 1830)

- House of Bourbon-Conti (extinct 1814)

- House of Bourbon-Soissons (extinct 1692)

- House of Bourbon-Saint Pol (extinct 1601)

- House of Bourbon-Montpensier, Dukes of Montpensier (extinct 1693)

- House of Bourbon, Kings of France

- House of Bourbon-Carency (extinct 1520)

- House of Bourbon-Duisant (extinct 1530)

- House of Bourbon-Préaulx (extinct 1442)

- House of Bourbon-Vendôme

- House of the Dukes of Bourbon (extinct 1521)

Families claiming to be a branch

- Bourbons of India, claiming to be descendants of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, of the first House of Bourbon-Montpensier

France

The rise of Henry IV

The first Bourbon king of France was Henry IV.[1] He was born on 13 December 1553 in the Kingdom of Navarre. Antoine de Bourbon, his father, was a ninth-generation descendant of King Louis IX of France.[1] Jeanne d'Albret, his mother was the Queen of Navarre and niece of King Francis I of France. He was baptized Catholic, but raised Calvinist. After his father was killed in 1562, he became Duke of Vendôme at the age of 10, with Admiral Gaspard de Coligny (1519–1572) as his regent. Seven years later, the young duke became the nominal leader of the Huguenots after the death of his uncle the Prince de Condé in 1569.

Henry succeeded to Navarre as Henry III when his mother died in 1572. That same year Catherine de' Medici, mother of King Charles IX of France, arranged for the marriage of her daughter, Margaret of Valois, to Henry, ostensibly to advance peace between Catholics and Huguenots. Many Huguenots gathered in Paris for the wedding on 24 August, but were ambushed and slaughtered by Catholics in the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. Henry saved his own life by converting to Catholicism. He repudiated his conversion in 1576 and resumed his leadership of the Huguenots.

The period from 1576 to 1584 was relatively calm in France, with the Huguenots consolidating control of much of the south with only occasional interference from the royal government. Extended civil war erupted again in 1584, when François, Duke of Anjou, younger brother of King Henry III of France, died, leaving Navarre next in line for the throne. Thus began the War of the Three Henrys, as Henry of Navarre, Henry III, and the ultra-Catholic leader, Henry of Guise, fought a confusing three-cornered struggle for dominance. After Henry III was assassinated on 31 July 1589, Navarre claimed the throne as the first Bourbon king of France, Henry IV.

Much of Catholic France, organized into the Catholic League, refused to recognize a Protestant monarch and instead recognized Henry IV's uncle, Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon, as rightful king, and the civil war continued. Henry won a crucial victory at Ivry on 14 March 1590 and, following the death of the Cardinal the same year, the forces of the League lacked an obvious Catholic candidate for the throne and divided into various factions. Nevertheless, as a Protestant, Henry IV was unable to take Paris, a Catholic stronghold, or to decisively defeat his enemies, now supported by the Spanish. He reconverted to Catholicism in 1593—he is said to have remarked, "Paris is well worth a mass"[2]—and was crowned king retroactively to 1589 at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594.

Early Bourbons in France

Henry granted the Edict of Nantes on 13 April 1598, establishing Catholicism as an official state religion but also granting the Huguenots a measure of religious tolerance and political freedom short of full equality with the practice of Catholicism. This compromise ended the religious wars in France. That same year the Treaty of Vervins ended the war with Spain, adjusted the Spanish-French border, and resulted in a belated recognition by Spain of Henry as king of France.

Ably assisted by Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully, Henry reduced the land tax known as the taille; promoted agriculture, public works, construction of highways, and the first French canal; started such important industries as the tapestry works of the Gobelins; and intervened in favor of Protestants in the duchies and earldoms along the German frontier. This last was to be the cause of his assassination.

Henry's marriage to Margaret, which had produced no heir, was annulled in 1599 and he married Marie de Medici, niece of the grand duke of Tuscany. A son, Louis, was born to them in 1601. Henry IV was assassinated on 14 May 1610 in Paris. Louis XIII was only nine years old when he succeeded his father.[1] He was to prove a weak ruler; his reign was effectively a series of distinct regimes, depending who held the effective reins of power. At first, Marie de Medici, his mother, served as regent and advanced a pro-Spanish policy. To deal with the financial troubles of France, Louis summoned the Estates General in 1614; this would be the last time that body met until the eve of the French Revolution. Marie arranged the 1615 marriage of Louis to Anne of Austria, the daughter of King Philip III of Spain.

In 1617, however, Louis conspired with Charles d'Albert, duc de Luynes to dispense with her influence, having her favorite Concino Concini assassinated on 26 April of that year. After some years of weak government by Louis's favorites, the King made Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu, a former protégé of his mother, the chief minister of France in 1624.

Richelieu advanced an anti-Habsburg policy. He arranged for Louis' sister, Henrietta Maria, to marry King Charles I of England, on 11 May 1625. Her pro-Catholic propaganda in England was one of the contributing factors to the English Civil War. Richelieu, as ambitious for France and the French monarchy as for himself, laid the ground for the absolute monarchy that would last in France until the Revolution. He wanted to establish a dominating position for France in Europe, and he wanted to unify France under the monarchy. He established the role of intendants, non-noble men whose arbitrary powers of administration were granted (and revocable) by the monarch, superseding many of the traditional duties and privileges of the noble governors.

Although it required a succession of internal military campaigns, he disarmed the fortified Huguenot towns that Henry had allowed. He involved France in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) against the Habsburgs by concluding an alliance with Sweden in 1631 and, actively, in 1635. He died in 1642 before the conclusion of that conflict, having groomed Cardinal Jules Mazarin as a successor. Louis XIII outlived him but by one year, dying in 1643 at the age of forty-two. After a childless marriage for twenty-three years his queen, Anne, delivered a son on 5 September 1638, whom he named Louis after himself.[1]

Louis XIV and Louis XV

Louis XIV succeeded his father at four years of age;[1] he would go on to become the most powerful king in French history. His mother Anne served as his regent with her favorite Jules, Cardinal Mazarin, as chief minister. Mazarin continued the policies of Richelieu, bringing the Thirty Years' War to a successful conclusion in 1648 and defeating the nobility's challenge to royal absolutism in a series of civil wars known as the Frondes. He continued to war with Spain until 1659.

In that year the Treaty of the Pyrenees was signed signifying a major shift in power, France had replaced Spain as the dominant state in Europe. The treaty called for an arranged marriage between Louis and his cousin Maria Theresa, a daughter of King Philip IV of Spain by his first wife Elisabeth, the sister of Louis XIII. They were married in 1660 and had a son, Louis, in 1661.[1] Mazarin died on 9 March 1661 and it was expected that Louis would appoint another chief minister, as had become the tradition, but instead he shocked the country by announcing he would rule alone.

For six years Louis reformed the finances of his state and built formidable armed forces. France fought a series of wars from 1667 onward and gained some territory on its northern and eastern borders. Maria Theresa died in 1683 and the next year he secretly married the devoutly Catholic Françoise d'Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon. Louis XIV began to persecute Protestants, undoing the religious tolerance established by his grandfather Henry IV, culminating in his revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

The last war waged by Louis XIV proved to be one of the most important to dynastic Europe. In 1700, King Charles II of Spain, a Habsburg, died without a son. Louis's son the Grand Dauphin, as the late king's nephew, was the closest heir, and Charles willed the kingdom to the Dauphin's second son, the Duke of Anjou. Other powers, particularly the Austrian Habsburgs, who had the next closest claims, objected to such a vast increase in French power.

Initially, most of the other powers were willing to accept Anjou's reign as Philip V, but Louis's mishandling of their concerns soon drove the English, Dutch and other powers to join the Austrians in a coalition against France. The War of the Spanish Succession began in 1701 and raged for 12 years. In the end Louis's grandson was recognized as king of Spain, but he was obliged to agree to the forfeiture of succession rights in France, the Spanish Habsburgs' other European territories were largely ceded to Austria, and France was nearly bankrupted by the cost of the struggle. Louis died on 1 September 1715 ending his seventy-two year reign, the longest in European history.

The reign of Louis XIV was so long that he outlived both his son and eldest grandson. He was succeeded by his great-grandson Louis XV.[1] Louis XV was born on 15 February 1710 and was thus aged only five at his ascension, the third Louis in a row to become king of France before the age of ten. Initially, the regency was held by Philip, Duke of Orléans, Louis XIV's nephew, as nearest adult male to the throne.[1] This Regence was seen as a period of greater individual expression, manifested in secular, artistic, literary and colonial activity, in contrast to the austere latter years of Louis XIV's reign.

Following Orléans' death in 1723, the Duke of Bourbon, representative of the Bourbon-Condé cadet line, became prime minister. It was expected that Louis would marry his cousin, the daughter of King Philip V of Spain, but this engagement was broken by the duke in 1725 so that Louis could marry Maria Leszczynska, the daughter of Stanislas, former king of Poland. Bourbon's motive appears to have been a desire to produce an heir as soon as possible so as to reduce the chances of a succession dispute between Philip V and the Duke of Orléans in the event of the sickly king's death. Maria was already an adult woman at the time of the marriage, while the infanta was still a young girl.

Nevertheless, Bourbon's action brought a very negative response from Spain, and for his incompetence Bourbon was soon replaced by Cardinal Andre Hercule de Fleury, the young king's tutor, in 1726. Fleury was a peace-loving man who intended to keep France out of war, but circumstances presented themselves that made this impossible.

The first cause of these wars came in 1733 when Augustus II, the elector of Saxony and king of Poland died. With French support, Stanislas was again elected king. This brought France into conflict with Russia and Austria who supported Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and son of Augustus II.

Stanislas lost the Polish crown, but he was given the Duchy of Lorraine as compensation, which would pass to France after his death. Next came the War of the Austrian Succession in 1740 in which France supported King Frederick II of Prussia against Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary. Fleury died in 1743 before the conclusion of the war.

Shortly after Fleury's death in 1745 Louis was influenced by his mistress the Marquise de Pompadour to reverse the policy of France in 1756 by creating an alliance with Austria against Prussia in the Seven Years' War. The war was a disaster for France, which lost most of her overseas possessions to the British in the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Maria, his wife, died in 1768 and Louis himself died on 10 May 1774.

French Revolution

Louis XVI had become the Dauphin of France upon the death of his father Louis, the son of Louis XV, in 1765. He married Marie Antoinette of Austria, a daughter of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, in 1770. Louis intervened in the American Revolution against Britain in 1778, but he is most remembered for his role in the French Revolution. France was in financial turmoil and Louis was forced to convene the Estates-General on 5 May 1789.

They formed the National Assembly and forced Louis to accept a constitution that limited his powers on 14 July 1790. He tried to flee France in June 1791, but was captured. The French monarchy was abolished on 21 September 1792 and a republic was proclaimed. The chain of Bourbon monarchs begun in 1589 was broken. Louis XVI was executed on 21 January 1793.

Marie Antoinette and her son, Louis, were held as prisoners. Many French royalists proclaimed him Louis XVII, but he never reigned. She was executed on 16 October 1793. He died of tuberculosis on 8 June 1795 at the age of ten while in captivity.[3]

The French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars spread nationalism and anti-absolutism throughout Europe, and the other Bourbon monarchs were threatened. Ferdinand was forced to flee from Naples in 1806 when Napoleon Bonaparte deposed him and installed his brother, Joseph, as king. Ferdinand continued to rule from Sicily until 1815.

Napoleon conquered Parma in 1800 and compensated the Bourbon duke with Etruria, a new kingdom he created from the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. It was short-lived, counting only two monarchs, Louis and Charles, as Napoleon annexed Etruria in 1807.

King Charles IV of Spain had been an ally of France. He succeeded his father, Charles III, in 1788. At first he declared war on France on 7 March 1793, but he made peace on 22 June 1795. This peace became an alliance on 19 August 1796. His chief minister, Manuel de Godoy convinced Charles that his son, Ferdinand, was plotting to overthrow him. Napoleon exploited the situation and invaded Spain in March 1808. This led to an uprising that forced Charles to abdicate on 19 March in favor of his son, Ferdinand VII. Napoleon forced Ferdinand to return the crown to Charles on 30 April and then convinced Charles to relinquish it to him on 10 May. In turn, he gave it to his brother, Joseph, king of Naples on 6 June. Joseph abandoned Naples to Joachim Murat, the husband of Napoleon's sister. This was very unpopular in Spain and resulted in the Peninsular War, a struggle that would contribute to the downfall of Napoleon.

The Bourbon Restoration

With the abdication of Napoleon on 11 April 1814 the Bourbon dynasty was restored to the kingdom of France in the person of Louis XVIII, brother of Louis XVI. Napoleon escaped from exile and Louis fled in March 1815. Louis was again restored after the Battle of Waterloo on 7 July.

The conservative elements of Europe dominated the post-Napoleonic age, but the values of the French Revolution could not be easily swept aside. Louis granted a constitution on 14 June 1814 to appease the liberals, but the ultra-royalist party, led by his brother, Charles, continued to influence his reign.[4] When he died in 1824 his brother became king as Charles X much to the dismay of French liberals. In a saying ascribed to Talleyrand, "they had learned nothing and forgotten nothing".[5]

Aftermath

Charles passed several laws that appealed to the upper class, but angered the middle class. The situation came to a head when he appointed a new minister on 8 August 1829 who did not have the confidence of the chamber. The chamber censured the king on 18 March 1830 and in response Charles proclaimed five ordinances on 26 July intended to silence criticism against him. This almost resulted in another revolution as dramatic as the one in 1789, but moderates were able to control the situation.

.svg.png)

As a compromise the crown was offered to Louis-Philippe, duke of Orléans, a descendant of the brother of Louis XIV, and the head of the Orleanist cadet branch of the Bourbons. Agreeing to reign constitutionally and under the tricolour, he was proclaimed King of the French on 7 August. The resulting regime, known as the July monarchy, lasted until the Revolution of 1848. The Bourbon monarchy in France ended on 24 February 1848, when Louis-Philippe was forced to abdicate and the short-lived Second Republic was established.

Some legitimists refused to recognize the Orleanist monarchy. After the death of Charles in 1836 his son was proclaimed Louis XIX, though this title was never formally recognized. Charles' grandson Henri, comte de Chambord, the last Bourbon claimant of the French crown, was proclaimed by some Henry V, but the French monarchy was never restored.

Following the 1870 collapse of the empire of Emperor Napoleon III, Henri was offered a restored throne. However Chambord refused to accept the throne unless France abandoned the revolution-inspired tricolour and accepted what he regarded as the true Bourbon flag of France, featuring the fleur-de-lis. The tricolour, originally associated with the French Revolution and the First Republic, had been used by the July Monarchy, the Second Republic and both Empires; the French National Assembly could not possibly agree.

A temporary Third Republic was established, while monarchists waited for the comte de Chambord to die and for the succession to pass to the Comte de Paris, who was willing to accept the tricolour. Henri lived until 1883, by which time public opinion had come to accept the republic as the "form of government that divides us least." His death without issue marked the extinction of the French Bourbons. Thus the head of the House of Bourbon became Juan, Count of Montizón of the Spanish line of the house who was also Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain, and had become the senior male of the dynasty by primogeniture. His heir as eldest Bourbon and head of the house is today Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou.

By an ordinance of Louis Philippe I of France of 13 August 1830, it was decided that the king's children (and his sister) would continue to bear the arms of Orléans, that Louis-Philippe's eldest son, as Prince Royal, would bear the title of duc d'Orléans, that the younger sons would continue to have their existing titles, and that the sister and daughters of the king would be styled Royal Highness and "d'Orléans", but the Orléans dynasts did not take the name "of France".

Bourbons of Spain and Italy

Philip V

The Spanish branch of the House of Bourbon was founded by Philip V. He was born in 1683 in Versailles, the second son of the Grand Dauphin, son of Louis XIV. He was Duke of Anjou and probably never expected to be raised to a rank higher than that. However King Charles II of Spain, dying without issue, willed the throne to his grand-nephew the Duke of Anjou, younger grandson of his eldest sister Marie-Thérèse, daughter of King Philip IV of Spain who had married Louis XIV of France.

The prospect of Bourbons on both the French and Spanish thrones was resisted as creating an imbalance of power in Europe by its dominant regimes and, upon Charles II's death on 1 November 1700, a Grand Alliance of European nations united against Philip. This was known as the War of Spanish Succession. In the Treaty of Utrecht, signed on 11 April 1713, Philip was recognized as king of Spain but his renunciation of succession rights to France was affirmed and, of the Spanish Empire's other European territories, Sicily was ceded to Savoy, and the Spanish Netherlands, Milan and Naples were allotted to the Austrian Habsburgs.

Philip had two sons by his first wife. After her death he married Elisabeth Farnese, niece of Francesco Farnese, Duke of Parma, in 1714. She presented Philip with three sons, for whom she had ambitions of securing Italian crowns. Thus she induced Philip to occupy Sardinia and Sicily in 1717.

A Quadruple Alliance of Britain, France, Austria and the Netherlands was organized on 2 August 1718 to stop him. In the Treaty of The Hague, signed on 17 February 1720, Philip renounced his conquests of Sardinia and Sicily, but assured the ascension of his eldest son by Elisabeth to the Duchy of Parma upon the reigning duke's death. Philip abdicated in January 1724 in favor of Louis I, his eldest son with his first wife, but Louis died in August and Philip resumed the crown.

When the War of the Polish Succession began in 1733, Philip and Elisabeth saw another opportunity to advance the claims of their sons and recover at least part of the former possessions of the Spanish crown on the Italian peninsula. Philip signed the Family Compact with Louis XV, his nephew and king of France. Charles, Duke of Parma since 1731, invaded Naples. At the conclusion of peace on 13 November 1738, control of Parma and Piacenza was ceded to Austria, which had occupied the duchies but was now forced to recognise Charles as King of Naples and Sicily. Philip also used the War of the Austrian Succession to win more territory in Italy. He did not live to see it to its conclusion, however, dying in 1746.

Ferdinand VI and Charles III

Ferdinand VI, second son of Philip V and his first wife, succeeded his father. He was a peace-loving monarch who kept Spain out of the Seven Years' War. He died in 1759 in the midst of that conflict and was succeeded by his half-brother Charles III. Charles was the eldest son of Philip and Elisabeth Farnese. He was born in 1716 and had become Duke of Parma when the last Farnese duke died in 1731.

Following Spain's victory over the Austrians at the battle of Bitonto, it proved inexpedient to reunite Naples and Sicily to Spain, so as a compromise Charles became King of Naples, as Charles IV and VII of Sicily. Following Charles' accession to the Spanish throne in 1759 he was required, by the Treaty of Naples of 3 October 1759, to abdicate Naples and Sicily to his third son, Ferdinand, thus initiating the branch known as the Neapolitan Bourbons.

Charles revived the Family Compact with France on 15 August 1761 and joined in the Seven Years' War against Britain in 1762; the reformist policies he had espoused in Naples were pursued with similar energy in Spain, where he completely overhauled the cumbersome bureaucracy of the state. As a French ally he opposed Britain during the American Revolution in June 1779, supplying large quantities of weapons and munitions to the rebels and keeping one third of all the British forces in the Americas occupied defending Florida and what is now Alabama, which were ultimately recaptured by Spain. Charles died in 1788.

Bourbons of Parma

Elisabeth Farnese's ambitions were realized at the conclusion of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748 when the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, already occupied by Spanish troops, were ceded by Austria to her second son, Philip, and combined with the former Gonzaga duchy of Guastalla. Elisabeth died in 1766.

Later Bourbon monarchs outside France

.svg.png)

Upon the fall of the French Empire, Ferdinand I was restored to the throne of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1815, founding the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. His subjects revolted in 1820 and he was forced to grant a constitution; Austria invaded in March 1821 and revoked the constitution. He was succeeded by his son, Francis I, in 1825 and by his grandson, Ferdinand II, in 1830. Another revolution erupted in January 1848 and Ferdinand was also forced to grant a constitution. This constitution was revoked in 1849. Ferdinand was succeeded by his son, Francis II, in May 1859.

When Giuseppe Garibaldi captured Naples in 1860, Francis restored the constitution in an attempt to save his sovereignty. He fled to the fortress of Gaeta, which was captured by the Piedmontese troops in February 1861; his kingdom was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy on 17 March 1861, after the fall the fortress of Messina (surrendered on 12 March), although the Neapolitan troops in Civitella del Tronto resisted three days longer.

After the fall of Napoleon, Napoleon's wife, Maria Louisa, was made Duchess of Parma. As compensation, Charles Louis, the former king of Etruria, was made the Duke of Lucca. When Maria Louisa died in 1847 he was restored to Parma as Charles II. Lucca was incorporated into Tuscany. He was succeeded by his son, Charles III, and grandson, Robert I, in 1854. The people of Parma voted for a union with the kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. After Italian unification the next year, the Bourbon dynasty in Italy was no more.

Ferdinand VII was restored to the throne of Spain in March 1814. Like his Italian Bourbon counterpart, his subjects revolted against him in January 1820 and he was forced to grant a constitution. A French army invaded in 1823 and the constitution was revoked. Ferdinand married his fourth wife, Maria Christina, the daughter of Francis I, the Bourbon king of Sicily, in 1829. Despite his many marriages he did not have a son, so in 1833 he was influenced by his wife to abolish the Salic Law so that her daughter, Isabella, could become queen depriving his brother, Don Carlos, of the throne.

Isabella II succeeded her father when he died in 1833. She was only three years old and Maria Cristina, her mother, served as regent. Maria knew that she needed the support of the liberals to oppose Don Carlos so she granted a constitution in 1834. Don Carlos found his greatest support in Catalonia and the Basques country because the constitution centralized the provinces thus denying them the autonomy they sought. He was defeated and fled the country in 1839. Isabella was declared of age in 1843 and she married her cousin Francisco de Asis, the son of her father's brother, on 10 October 1846. A military revolution broke out against Isabella in 1868 and she was deposed on 29 September. She abdicated in favor of her son, Alfonso, in 1870, but Spain was proclaimed a republic for a brief time.

When the First Spanish Republic failed the crown was offered to Isabella's son who accepted on 1 January 1875 as Alfonso XII. Don Carlos, who returned to Spain, was again defeated and resumed his exile in February 1876. Alfonso granted a new constitution in July 1876 that was more liberal than the one granted by his grandmother. His reign was cut short when he died in 1885 at the age of twenty-eight.

Alfonso XIII was born on 17 May 1886 after the death of his father. His mother, Maria Christina, the second wife of Alfonso XII served as regent. Alfonso XIII was declared of age in 1902 and he married Victoria Eugénie Julia Ena of Battenberg, the granddaughter of the British queen Victoria, on 31 May 1906. He remained neutral during World War I, but supported the military coup of Miguel Primo de Rivera on 13 September 1923. A movement towards the establishment of a republic began in 1930 and Alfonso fled the country on 14 April 1931. He never formally abdicated, but lived the rest of his life in exile. He died in 1941.

The Bourbon dynasty seemed finished in Spain as in the rest of the world, but it would be resurrected. The Second Spanish Republic was overthrown in the Spanish Civil War, leading to the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. He named Juan Carlos de Borbón, a grandson of Alfonso XIII, his successor in 1969. When Franco died six years later, Juan Carlos I took the throne to restore the Bourbon dynasty. The new king oversaw the Spanish transition to democracy; the Spanish Constitution of 1978 recognized the monarchy.

Since 1964 the Bourbon-Parma line has reigned agnatically in Luxembourg through Grand Dukes Jean and his son Henri. In June 2011, Luxembourg adopted absolute primogeniture, replacing the old Semi-Salic law that might have guaranteed the survival of Bourbon rule for generations.

Though it is not as powerful as it once was and no longer reigns in its native country of France, the House of Bourbon is by no means extinct and has survived to the present-day world, predominantly composed of republics.

The House of Bourbon, in its surviving branches, is believed to be the oldest royal dynasty of Europe (and the oldest documented European family altogether) that is still existing in the direct male line today: The House of Capet's male ancestors, the Robertians, go back to Robert of Hesbaye (d. 807) as their first secured ancestor and he is believed to be a direct male descendant of Charibert de Haspengau (c. 555–636). Should this be true, only the Imperial House of Japan would outmatch the Bourbon's age, being reliably documented - as a ruling house already - from about 540. The House of Hesse traces its line back to 841, the House of Welf-Este and the House of Wettin are both emerging in the 10th century (and so do some Italian non-ruling houses like the Caetani or the Massimo family), whereas most of the other ruling families of Europe only turn up to the light of history after the year 1000.

List of Bourbon rulers

France

Monarchs of France

Dates indicate reigns, not lifetimes.

- Henry IV, the Great (1589–1610)

- Louis XIII, the Just (1610–1643)

- Louis XIV, the Sun King (1643–1715)

- Louis XV, the Well-Beloved (1715–1774)

- Louis XVI (1774–1792)

Claimants to the throne of France

Dates indicate claims, not lifetimes.

- Louis XVI (1792–1793)

- Louis XVII (1793–1795)

- Louis XVIII (1795–1814)

Monarchs of France

Dates indicate reigns, not lifetimes.

- Louis XVIII (1814–1824)

- Charles X (1824–1830)

- Louis-Philippe (House of Bourbon-Orléans) (1830–1848)

Legitimist claimants in France

Dates indicate claims, not lifetimes.

- Charles X (1830–1836)

- Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême (Louis XIX) (1836–1844)

- Henri, Count of Chambord (Henri V) (1844–1883)

Legitimist claimants in France (Spanish branch)

Dates indicate claims, not lifetimes.

- Juan, Count of Montizón (Jean III) (1883–1887)

- Carlos, Duke of Madrid (Charles XI) (1887–1909)

- Jaime, Duke of Anjou and Madrid (Jacques I) (1909–1931)

- Alfonso Carlos, Duke of San Jaime (Charles XII)(1931–1936)

- Alfonso XIII of Spain (Alphonse I) (1936–1941) (did not claim the Throne of France[6])

- Jaime, Duke of Segovia (Jacques II / Henri VI) (1941–1975)

- Alfonso, Duke of Anjou and Cádiz (Alphonse II) (1975–1989)

- Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou (Louis XX) (1989–present)

Orléanist and Unionist claimants in France

Dates indicate claims, not lifetimes.

- Prince Philippe, Count of Paris (Philippe VII) (1883–1894)

- Prince Philippe, Duke of Orléans (Philippe VIII) (1894–1926)

- Prince Jean, Duke of Guise (Jean III) (1926–1940)

- Prince Henri, Count of Paris (Henry VI) (1940–1999)

- Prince Henri, Count of Paris (Henry VII) (1999 – Present)

Kingdom of Spain

Monarchs of Spain

Dates indicate seniority, not lifetimes. Where reign as king or queen of Spain is different, this is noted.

- Philip V (1700–1746) [abdicated 1724, resumed throne on death of son]

- Louis I [King 1724; ruled less than one year]

- Ferdinand VI (1746–1759)

- Charles III (1759–1788)

- Charles IV (1788–1808)

- Ferdinand VII, El Deseado (1808–1833) [King 1808, 1813–1833]

- Isabella II (1833–1870) [Queen 1833–1868]

- Alfonso XII (1870–1885) [King 1874–1885]

- Alfonso XIII (1886–1941) [King 1886–1931]

- Juan, Count of Barcelona (1941–1977) [did not become King]

- Juan Carlos I (1977–2014) [King 1975–2014]

- Felipe VI (2014–present) [King 2014–present]

"Carlist" claimants in Spain

Dates indicate claims, not lifetimes.

- Infante Carlos, Count of Molina (Carlos V) (1833–1845)

- Infante Carlos, Count of Montemolin (Carlos VI) (1845–1861)

- Juan, Count of Montizón (Juan II) (1861–1868)

- Carlos, Duke of Madrid (Carlos VII) (1868–1909)

- Jaime, Duke of Madrid (Jaime III) (1909–1931)

- Alfonso Carlos of Bourbon, Duke of San Jaime (Alfonso Carlos I) (1931–1936)

- Xavier, Duke of Parma (Xavier I) (1936–1952–1977)

- Carlos Hugo of Bourbon, Duke of Parma (Carlos Hugo I) (1977–1979)

- Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma (Sixto Enrique I) (1979–present)

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Grand Dukes of Luxembourg

Dates indicate reigns, not lifetimes.

Other significant Bourbon titles

- Dukes of Bourbon, Montpensier, Vendôme, Anjou, Kings of the Two Sicilies, Dukes of Parma, Dukes of Orléans, Princes of Orléans and Braganza

- Princes of Condé

- Princes of Conti

Surnames used

Officially, the King of France had no family name. A prince with the rank of fils de France (Son of France) is surnamed "de France"; all the male-line descendants of each fils de France, however, took his main title (whether an appanage or a courtesy title) as their family or last name. However, when Louis XVI was put on trial and later "guillotined" (executed) by the revolutionaries National Convention in France in 1793, they somewhat contemptously referred to him in written documents and spoken address as "Citizen Louis Capet" as if a "commoner" (referring back to the Medieval origins of the Bourbon Dynasty's name and referring to Hugh Capet, founder of the Capetian Dynasty).

Members of the House of Bourbon-Condé and its cadet branches, which never ascended to the throne, used the surname "de Bourbon" until their extinction in 1830.

The daughters of Gaston, Duke of Orleans, were the first members of the House of Bourbon since the accession of Henry IV to take their surname from the appanage of their father (d'Orleans). Gaston died without a male heir; his titles reverted to the crown. It was given to his nephew, Philippe I, Duke of Orleans, brother of Louis XIV, whose descendants still bear the surname.

When Philippe, grandson of Louis XIV, became King of Spain as Philip V, he gave up his French titles. As a Son of France, his actual surname was "de France". However, since that surname was not heritable for descendants of rank lower than Son of France, and since Philippe had already given up his French titles, his descendants simply took the name of their royal house as their surname ("de Bourbon", rendered in Spanish as "de Borbón").

The children of Philippe's brother, Charles, Duke of Berry (all of whom died in infancy), were given the surname "d'Alencon". He was Duke of Berry only in name, so the surname of his children was taken from his first substantial duchy.

The children of Charles Philippe, Count of Artois, brother of Louis XVI, were surnamed "d'Artois". When Charles succeeded to the throne as Charles X, his son Louis Antoine became a Son of France, with the corresponding change in surname. His grandson, Henri d'Artois, being merely a Grandson of France, would use the surname until his death.

Family trees

Simplified family trees showing the relationships between the Bourbons and the other branches of the Royal House of France.

From Louis IX to Henry IV

Simplified Relationships between the Branches of the House of Bourbon

Below is a simplified picture showing the relationships between the lines of the House of Bourbon.

Descent from Henry IV

Henry IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis XIII | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis XIV | Philippe I Duke of Orléans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis "Le Grand Dauphin" of France | Philippe II Duke of Orléans Regent of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis "Le Petit Dauphin" of France | Philip V | Louis Duke of Orléans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis XV | Louis I | Ferdinand VI | Charles III | Philip Duke of Parma (1748–65) | Louis Philippe I Duke of Orléans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis Dauphin of France | Charles IV | Ferdinand Duke of Parma (1765–1802) | Louis Philippe II (Philippe Égalité) Duke of Orléans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis XVI Titular King of France (1792–93) | Louis XVIII Legitimist pretender (1804–14) | Charles X Legitimist pretender (1830–36) | Ferdinand VII | Francisco de Paula | Carlos Count of Molina as Carlos V | Louis I | Louis-Philippe I Orléanist Pretender (1848-50) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Louis Dauphin of France as Louis XVII | Louis-Antoine Duke of Angoulême Dauphin of France as Louis XIX | Charles Ferdinand Duke of Berry | Isabella II | Francis Duke of Cádiz King consort of Spain | Carlos Count of Montemolin as Carlos VI | Juan Count of Montizón as Juan III as Jean III | Louis II as Charles I as Charles II Duke of Parma (1847–48) | Ferdinand Philippe Duke of Orléans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Henri Count of Chambord as Henri V | Alfonso XII | Carlos Duke of Madrid as Carlos VII as Charles XI | Alfonso Carlos Duke of San Jaime as Alfonso Carlos I as Charles XII | Charles III | Philippe Count of Paris as Philippe VII | Robert Duke of Chartres | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Francisco Franco Regent of the Kingdom (1947–75) | Alfonso XIII as Alphonse I | Jaime Duke of Madrid as Jaime III as Jacques I | Robert I | Philippe Duke of Orléans as Philippe VIII | Jean Duke of Guise as Jean III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carmen Franco y Polo 1st Duchess of Franco | Jaime Duke of Segovia as Jaime IV as Jacques II or Henri VI | Juan Count of Barcelona | Xavier Duke of Parma as Javier I | Felix Prince of Luxembourg | Henri Count of Paris as Henri VI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| María del Carmen Martínez-Bordiú y Franco | Alfonso Duke of Anjou and Cádiz as Alfonso XIV as Alphonse II | Juan Carlos I | Carlos Hugo Duke of Parma as Carlos Hugo I | Sixtus Henry Prince of Parma as Enrique V | Jean | Henri Count of Paris Duke of France as Henri VII | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis Duke of Anjou as Louis XX as Luis II | Felipe VI | Carlos Duke of Parma as Carlos Xavier II | Henri | Jean Duke of Vendome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis Duke of Burgundy, Dauphin of France | Guillaume Hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- List of living legitimate male Capetians

- Capetian Armorial

- Members of the House of Bourbon

- Bourbon County, Kentucky, USA, named after the royal family

- Bourbonnais

- Bourbons of India and the controversy about them.

- French Wars of Religion

- Image:Habsburg-bourbon-parma-2siciliesX.png: A chart of the dynastic links among the royal houses of Habsburg, Bourbon, Bourbon-Parma and Bourbon-Two Sicilies

- Le Retour des Princes Français à Paris

- Legitimists

- List of Spanish monarchs

- List of monarchs of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Anselme, Père. ‘’Histoire de la Maison Royale de France’’, tome 4. Editions du Palais-Royal, 1967, Paris. pp. 144-146, 151-153, 175, 178, 180, 185, 187-189, 191, 295-298, 318-319, 322-329. (French).

- ↑ Frieda, Leonie, Catherine de Medici

- ↑ "The heart of Louis XVII, the son of Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI who died in prison in 1795, has been laid to test in the crypt of Saint-Denis Basilica.(News)(Brief Article)." History Today. History Today Ltd. 2004. HighBeam Research. 18 Sep. 2012;"Louis XVII officially died of TB at the age of ten in the Temple prison."

- ↑ Durant, Will and Durant, Ariel. “The Story of Civilization, Part XI, The Age of Napoleon”. Simon & Schuster, New York, 1975. pp. 730-731, 774.

- ↑ In French: Ils n'ont rien appris, ni rien oublié. There is no historic evidence linking the saying to Talleyrand. It may derive from a similar lamentation about the royalists, found in a letter by Charles Louis Etienne, chevalier de Panat, a French naval officer, dated January 1796 and sent from London to Mallet du Pan: personne n'a su ni rien oublier, ni rien apprendre ("nobody has been able to forget anything, nor to learn anything"), included in: A. Sayou, ed. (1852). Mémoires et correspondance de Mallet du Pan II. p. 197.

- ↑ "Documents relating to the Spanish succession".

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bourbon. |

- Bergamini, John D. The Spanish Bourbons: The History of a Tenacious Dynasty. Putnam, 1974.

- Petrie, Sir Charles. The Spanish Royal House. Geoffrey Bles, 1958.

- Seward, Desmond. The Bourbon Kings of France. Barnes & Noble, 1976.

- Van Kerrebrouck, Patrick. La Maison de Bourbon, 1256–1987. ___v. Villeneuve d'Ascq, France: The Author, 1987–2000. [only Vol. 2 & Vol. 4 have been published as of 2005].

- J. H. Shennan, The Bourbons: The History of a Dynasty (London, Hambledon Continuum, 2007).

- Klaus Malettke, Die Bourbonen. Band I: Von Heinrich IV. bis Ludwig XV. 1589–1715 (Stuttgart, W. Kohlhammer, 2008); Band II: Von Ludwig XV. bis Ludwig XVI. 1715-1789/92 (Stuttgart, W. Kohlhammer, 2008); Band III: Von Ludwig XVIII. bis zu Louis Philippe 1814–1848 (Stuttgart, W. Kohlhammer, 2009).

| — Royal house — House of Bourbon Cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty Founding year: 1272 | ||

| Preceded by House of Valois |

Ruling House of France 1589–1792 |

Monarchy Abolished See French Revolution; eventually House of Bonaparte |

| Preceded by House of Bonaparte Ruled as French Emperor |

Ruling House of France 1814–1830 |

Succeeded by House of Orléans |

| Preceded by House of Habsburg |

Ruling House of the Duchy of Burgundy and the Burgundian Netherlands 1700–1713 |

Succeeded by House of Habsburg |

| Ruling House of Spain 1700–1808 |

Succeeded by House of Bonaparte | |

| Vacant Title last held by House of Trastámara |

Ruling House of Naples and Sicily 1753–1806 | |

| Preceded by House of Bonaparte |

Ruling House of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies 1815–1860 |

Kingdom Abolished Italian Unification under the House of Savoy |

| Ruling House of Spain 1813–1868 |

Interregnum Bourbon Monarchy overthrown in Glorious Revolution; eventually House of Savoy | |

| Vacant Title last held by House of Savoy |

Ruling House of Spain 1885–1931 |

Second Republic Declared |

| Vacant Title last held by House of Bourbon |

Ruling House of Spain 1975–present |

Incumbent |

| Preceded by House of Nassau-Weilburg |

Ruling House of Luxembourg 1964–present | |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)