Horned deity

Deities depicted with horns or antlers are found in many different religions across the world.

Horned goddess Hathor

Hathor is commonly depicted as a cow goddess with head horns in which is set a sun disk with Uraeus. Twin feathers are also sometimes shown in later periods as well as a menat necklace. Hathor may be the cow goddess who is depicted from an early date on the Narmer Palette and on a stone urn dating from the 1st dynasty that suggests a role as sky-goddess and a relationship to Horus who, as a sun god, is "housed" in her.

Hathor had a complex relationship with Ra, in one myth she is his eye and considered his daughter but later, when Ra assumes the role of Horus with respect to Kingship, she is considered Ra's mother. She absorbed this role from another cow goddess 'Mht wrt' ("Great flood") who was the mother of Ra in a creation myth and carried him between her horns. As a mother she gave birth to Ra each morning on the eastern horizon and as wife she conceives through union with him each day.

Bat was a cow goddess in Egyptian mythology depicted as a human face with cow ears and horns. By the time of the Middle Kingdom her identity and attributes were subsumed within the goddess Hathor. The worship of Bat dates to earliest times and may have its origins in Late Paleolithic cattle herding. Bat was the chief goddess of Seshesh, otherwise known as Hu or Diospolis Parva, the 7th nome of Upper Egypt. The imagery of Bat as a divine cow was remarkably similar to that of Hathor the parallel goddess from Lower Egypt. The significant difference in their depiction is that Bat's horns curve inward and Hathor's curve outward slightly. It is possible that this could be based in the different breeds of cattle herded at different times.

Cult of the bull deities

In Egypt, the bull was worshiped as Apis, the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. A long series of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god's priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and encased in a giant sarcophagus. A long sequence of monolithic stone sarcophagi were housed in the Serapeum, and were rediscovered by Auguste Mariette at Saqqara in 1851. The bull was also worshipped as Mnevis, the embodiment of Atum-Ra, in Heliopolis. Ka in Egyptian is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull.

Mnevis was identified as being a living bull. This may be a vestige of the sacrifice of kings after a period of reign, who were seen as the sons of Bat or Hathor (see:horned goddess Hathor), the ancient cow deity of the early solar cults. Thus, seen as a symbol of the later sun god, Ra, the Mnevis was often depicted, in art, with the solar disc of their mother, Hathor between its horns.

The Canaanite deity Moloch (according to the bible) was often depicted as a bull, and became a bull demon in Abrahamic traditions. The bull is familiar in Judeo-Christian cultures from the Biblical episode wherein an idol of the Golden Calf is made by Aaron and worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of Sinai (Exodus). The text of the Hebrew Bible can be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representing the God of Israel himself, perhaps through an association or syncretization with Egyptian or Levantine bull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.

Exodus 32:4 "He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, 'This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt'."

Nehemiah 9:18 "even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, 'This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!' They committed terrible blasphemies."

Calf-idols are referred to later in the Tanakh, such as in the Book of Hosea, which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures.

King Solomon's "bronze sea"-basin stood on twelve brazen bulls, according to 1. Kings 7:25.

Young bulls were set as frontier markers at Tel Dan and at Bethel the frontiers of the Kingdom of Israel.

Ram deities in ancient Egypt

The ram was revered in ancient Egypt in matters of fertility and war. Early gods with long wavy ram horns include Khnum and the equivalent god in Lower Egypt, Banebdjedet, the "Ram Lord of Djedet" (Mendes), who was typically shown with four ram heads to represent the four souls (Ba) of the sun god.[1] Banebdjedet may also be linked to the first four gods to rule over Egypt, Osiris, Geb, Shu and Ra-Atum, with large granite shrines devoted to each in the Mendes sanctuary. The Book of the Heavenly Cow describes the "Ram of Mendes" as being the Ba of Osiris, but this was not an exclusive association.[1]

List of Egyptian gods associated with the ram:

- Khnum (one of the earliest Egyptian deities)

- Heryshaf (a ram god of Heracleopolis)

- Kherty (a variant of Aken, The chief deity in Egyptian mythology)

- Andjety (precursor of Osiris, Auf "Efu Ra").

- Horem Akhet (a god depicted as a sphinx with the head of a man, lion, or ram)

- Banebdjedet (ram god linked to the first four Egyptian gods: Osiris, Geb, Shu, Ra-Atum)

- Amun (the ram deity that inspired the cult of Ammon)

Cult of Ammon

The worship of Ammon was introduced into Greece at an early period, probably through the medium of the Greek colony in Cyrene, which must have formed a connection with the great oracle of Ammon in the Oasis soon after its establishment. Ammon had a temple and a statue, the gift of Pindar, at Thebes,[2] and another at Sparta, the inhabitants of which, as Pausanias says,[3] consulted the oracle of Ammon in Libya from early times more than the other Greeks. At Aphytis, Chalcidice, Ammon was worshipped, from the time of Lysander, as zealously as in Ammonium. Pindar the poet honoured the god with a hymn. At Megalopolis the god was represented with the head of a ram (Paus. viii.32 § 1), and the Greeks of Cyrenaica dedicated at Delphi a chariot with a statue of Ammon.

Such was its reputation among the Classical Greeks that Alexander the Great journeyed there after the battle of Issus and during his occupation of Egypt, where he was declared the son of Amun by the oracle. Alexander thereafter considered himself divine. Even during this occupation, Amun, identified by these Greeks as a form of Zeus,[4] continued to be the principal local deity of Thebes.

The Cyrenaican Greeks built temples for the Libyan god Amon instead of their original god Zeus. They later identified their supreme god Zeus with the Libyan Amon.[5] Some of them continued worshipping Amon himself. Amon's cult was so widespread among the Greeks that even Alexander the Great decided to be declared as the son of Zeus in the Siwan temple by the Libyan priests of Amon.[6]

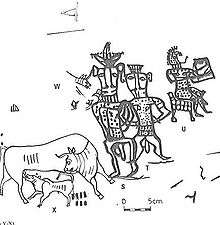

Although the most modern sources ignored the existence of Amun in the Berber mythology, he was maybe the greatest ancient Berber god.[7] He was honored by the Ancient Greeks in Cyrenaica, and was united with the Phoenician/Carthaginian god Baal-hamon due to Libyan influence.[8] Some depictions of the ram across North Africa belong to the lythic period which is situated between 9600 BC and 7500 BC.

The most famous Amun's temple in Ancient Libya was the temple at the oasis of Siwa.

The name of the ancient Berber tribes: Garamantes and Nasamonians are believed by some scholars to be related to the name Amon.[9]

In Awelimmiden Tuareg, the name Amanai is believed to have the meaning of "God". The Ancient Libyans may have worshipped the setting sun, which was personified by Amon, who was represented by the ram's horns.[10]

In Carthage and North Africa Baal-hamon was especially associated with the ram and was worshiped also as Baʿal Qarnaim ("Lord of Two Horns") in an open-air sanctuary at Jebel Bu Kornein ("the two-horned hill") across the bay from Carthage.

The Egyptian god Ammon-Ra was depicted with ram horns. Rams were considered a symbol of virility due to their rutting behavior. The horns of Ammon may have also represented the East and West of the Earth, and one of the titles of Ammon was "the two-horned." Alexander was depicted with the horns of Ammon as a result of his conquest of ancient Egypt in 332 BC, where the priesthood received him as the son of the god Ammon, who was identified by the ancient Greeks with Zeus, the King of the Gods. The combined deity Zeus-Ammon was a distinct figure in ancient Greek mythology. According to five historians of antiquity (Arrian, Curtius, Diodorus, Justin, and Plutarch), Alexander visited the Oracle of Ammon at Siwa in the Libyan desert and rumors spread that the Oracle had revealed Alexander's father to be the deity Ammon, rather than Philip.[11][12][13] Alexander styled himself as the son of Zeus-Ammon and even demanded to be worshiped as a god:

He seems to have become convinced of the reality of his own divinity and to have required its acceptance by others ... The cities perforce complied, but often ironically: the Spartan decree read, 'Since Alexander wishes to be a god, let him be a god.' [14]

Horned deities by continent

Europe

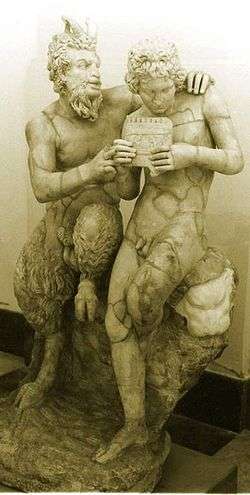

Pan was a god of shepherds and flocks, of mountain wilds and rustic music.

Depictions in Celtic cultures of figures with antlers are often identified as Cernunnos ("horned one" in Latin). The prime evidence for this comes from a pillar in Paris which also features the Roman god Jupiter.[15]

Cocidius was the name of a Romano-British war-god and local deity from the area around Hadrian's Wall, who is sometimes represented as being horned.[16] He is associated with warfare and woodland and was worshipped mostly by military personnel and the lower classes.[17]

Eliphas Levi, the 18th century occultist, believed that the pseudohistorical god Baphomet (that the Roman Catholic Church had claimed was worshipped by the heretical Knights Templar), was actually the horned Libyan oracle god (Ammon), or, the Goat of Mendes.[18]

For many years scholars have interpreted the Gundestrup Cauldron's images in terms of the Celtic pantheon. The antlered figure in plate A has been commonly identified as Cernunnos.

Africa

A ram-shaped oracle god whose name is unknown was worshiped by Libyan tribes at Siwa. The figure was incorporated by the Egyptians into depictions of their god Amun that's considered an "Interpretatio graeca" of the Greek Zeus-Ammon.[19]

Adherents of Odinani (the traditional folk religion of the Igbo people of south-eastern Nigeria) worship the Ikenga, a horned god of honest achievement, whose two horns symbolise self-will. Small wooden statues of him are made and praised as personal altars.[20]

Asia

The Pashupati seal, a seal discovered during the excavation of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan has drawn attention as a possible representation of a "proto-Shiva" figure.[21] This "Pashupati" (Lord of animal-like beings – Sanskrit paśupati)[22] seal shows a seated figure with horns, possibly ithyphallic, surrounded by animals.[23]

Mukhtar Ahmed, in discussing the deities of the Indus Valley Civilization, points that their identity and natures are problematic. Archaeologists have yet to find prominent temples and shrines to these deities, and the people may have instead worsipped in the open. There is doubt that the religion of this Civilization had formed a full pantheon. Instead of a more developed polytheism, this religion could be a mix of superstition, animism, and shamanism.[24]

Deities of this Civilization are known from seals, figurines, pottery paintings, and inscriptive notations. No names survive but Ahmed assigns descriptive names on these deities.[24] Prominent among them was a male horned deity, whom Ahmed nicknames "the Buffalo God". The God is depicted seating on a throne-like stool with hoofed legs. He is sometimes depicted as a solitary figure, while other depictions have him surrounded by animal companions. His horns are curved, resembling a buffalo.[25]

The deity wears headgear. From his headgear sprout three branches of leaves.[25] There are also images of him with no horns and no headgear. But he can be recognized by his posture on the throne, which is still depicted.[25] The deity is most often depicted on soapstone seals, terracotta tablets, and small copper plates.[25] His most famous depiction is on the so-called "Seal 420" (Pashupati seal), discovered on Mohenjo-daro by Ernest J. H. Mackay. The seal can dated to either the 23rd century BC or the 22nd century BC.[25]

The deity on the Seal sits on a dais with his body erect. His back is straight, his head up and alert. His legs are bent beneath him, heels together and toes down. His arms are covered with bangles. The hands are outstretched, reaching his knees. His head includes a pair or large buffalo horns. The headgear with the three branch leaves also appears. The deity is surrounded by four animal figures: an elephant, a rhinoceros,a tiger, and a water buffalo. Beneath the dais are two other horned animals, antelopes or ibexes. The seal includes seven logogram, one of which seems to represent a human figure.[25]

John Marshall saw the horned deity as having three faces and seated in a "yoga posture". He theorized the deity was a prototype for the god Shiva, the "Lord of Cattle". Ahmed points that Shiva is a later-day figure who does not appear at all in the Rigveda. There, the "master of beasts" is Rudra.[25]

"Seal 220", also found in Mohenjo-daro, is similar to Seal 420 and also depicts the horned deity. The god seats on a stool with legs shaped like bovine hooves. There appear to be more than one faces on the god, making another possible depiction of the "three-faced, buffalo horned deity". His body includes well-defined pectoral muscles and stylized male genitalia.The headgear with the branches is also depicted. The deity stands alone, with no animal companions.[25]

Two other seals also depict the horned deity. One is similar to Seal 420 and includes animal companions. Only a tortoise is recognizable among them. The other seal has the god without his horns, but with the same distinctive posture. His animal companions on this seal are two cobras. Two human figures make offerings to the god.[25]

Another depiction of the horned deity was found in a tablet Harappa. The deity wears horned headgear, seats on a stool, and seems to be in the so-called yoga position. The tablet has been considerably damaged, erasing whatever other details it originally included.[25] Another depiction of the horned deity was found in a tablet of Ganeriwala. The god seats on a pedestal. His legs are bent. Under the pedestal is a human figure in a supplicant position, with a jar in his hands. Probably making an offering to the god. The tablet is broken, so it is unclear if it originally included other figures. No animal companions.[25]

The horned deity also appears in a terracotta "cake" from Kalibangan. Here an animal figure is dragged by a human, implying an imminent animal sacrifice.[25] There are additional depictions of the horned deity appearing in his typical posture. Not all include his horns.[25] In one tablet the horned deity appears as a spectator. Before him, a human figure fights with a buffalo. In another, the god stands within a tree trunk. A goat is offered to him as a sacrifice. Both tablets include the horns.[25]

John Marshall originally identified the horns of the god as resembling those of a bull. Later researchers corrected that these more resembled buffalo horns.[25] The buffalo may have had a religious significance for the civilization. A pot from Kot Diji depicts a buffalo with a seemingly human face.[25]

The theory of Marshall that the horned deity is a proto-Shiva was based on four observations. One, the horned deity is depicted with three faces in Seal 420 and Siva has been on occasion depicted with three faces as well. Though Shiva is usually depicted with five faces. Second, the supposed bull horns of the horned deity resemble a trishula. Both the bull and the trishula are symbols of Shiva. Third, the supposed yoga posture of the horned deity were found reminiscent of a Mahayogi. And Mahayogi is one of the titles of Shiva. Four, the horned deity in Seal 420 is surrounded by animals. He is a Pashupati, "Lord of animals". And Pashupati is an incarnation of Shiva.[25]

The theory of Marshall suggests that Shiva originates from the religion of Indus Valley Civilization and predates the Aryans' arrival in the Punjab region.[25] His theory has endured and influenced the understanding of Hindu art and Hinduism.[25] Ahmed however raised doubts on the long established theory. He suggests the horned deity in Seal 420 could represent not Shiva but a holy person or shaman in the process of communicating with wild animals.[25]

He is not the first to doubt that the horned deity is Shiva. B. A. Saletore viewed the figure in Seal 420 as having three faces and a headgear with three horns, not two. He suggested there were two sideways horns and one in the middle. He theorized that the figure is not Shiva but Agni. According to his theory, the faces are the three faces of Agni and the horns represent his flames.[25]

Nirad C. Chaudhuri also opposed Marshall's theory. In his view the attributes of Shiva would not be established until the works of the Indian epic poetry and the Puranas, long after the end of the Indus Valley Civilization. The time gap itself places doubts on the identification. Also, other than the trishula, the aspects of Shiva that Marshall highlighted are uncommon in the iconography of Shiva. He also doubted that the headgear of the horned god stands for the trishula.[25]

K. A. Nilakanta Sastri also opposed Marshall's theory. In his view, the horned deity is not three-faced after all. He also argued that the horned god is not human-faced. His form is humanoid but represents a combination of various animals.[25]

Herbert P. Sullivan theorized that the horned god is actually a goddess. According to his theory, the deity lacks a phallus. Marshall himself was not certain if the deity has a phallus or only a waistband. Sullivan agreed that it was only a waistband. He argues that waistbands are typical of female figurines, while male figurines were depicted nude. The deity also wears arm bangles and necklace. He argued that the use of lavish jewellery also suggests a female figure. The headgear with the branches resembles the headgear of a tree goddess of the same Civilization. He believed that the horned goddess may represent the cult of the Great Goddess.[25] Shubhangana Atre also supported the theory that is a horned goddess, not a god.[25]

Herbert P. Sullivan had further arguments against the Indus Valley Civilization worshiping Shiva. Marshall believed that the Civilization created phallic symbols suggestive of Shiva Linga. But Sullivan pointed that the phallic-like stones found in sites of the Civilization acan not be certainly identified with the Lingam. Even if there was phallus worship in the Civilization, this need not represent the worship of a proto-Shiva. The association of the Lingam itself with Rudra/Shiva does not occur in the Vedas, nor in the works of Patanjali. Suggesting that the Lingam became associated with the Shiva cult at a relatively late date. There is no attestation of the Lingam before the 1st century BC[25]

Shereen Ratnagar also disputed the "yoga" posture of the horned god as connecting him to Shiva. She argued that the association of Shiva with yoga was itself a much later addition to his cult, since the association of yoga with asceticism was only attested very late in the Puranas. It did not predate the 1st millennium. She attributed the addition to the Shiva cult to the Brahmins, who conceived Shiva as a Yogi. Shiva was not depicted in iconography prior to the 2nd century BC. She points that Shiva was not part of the Historical Vedic religion and certainly too young a figure to be associates with the Indus Valley Civilization.[25]

Ahmed points that there is a god with Shiva's powers in the Rigveda: Rudra. He was later identified with Shiva. The horned god could be seen as a predecessor of Rudra, though this is also disputed. Marshall explained that the term Pashupati for the deities derives from "pashu" or "pasu", a Vedic Sanskrit term for the beasts of the jungle. He stated as the source of his etymology the Vedic Index by Arthur Anthony Macdonell and Arthur Berriedale Keith. However, Ahmed points that this work does not support this etymology.[25]

According to R. G. Bhandarkar, Pashupati is Rudra as a destroyer of grazing cattle. In this form, the god is dressed in skins as a tribesman and is equipped as an archer. When beseeched to refrain from killing them, the god becomes a protector of pastoralists. In this form Pashupati becomes pashupa (protector of cattle).[25] Rudra in the Vedas is not a protector of wild animals. He is wrathful towards them. in the Yajurveda, Pashupati dwells away from the human settlements. He is a lord of the forest, the trees, and the cattle. In the Atharvaveda, Rudra/Pashupati is associated with people, cattle, goats, horses, and sheep. Not wild animals.[25] Ahmed concludes that Rudra/Pashupati is neither a tamer, nor a protector of dangerous beasts. While the horned god is associated with the elephant, the rhinoceros, and the tiger.[25]

Gregory Possehl pointed that there is no conclusive proof that the horned god in Seal 420 is a god at all. Though, Possehl himself supported the idea that he is a god after all. "The look of the figure elicits an irresistible conclusion for me- it is a god because it looks like a god!" Possehl added that the posture of the god in both Seal 420 and its other depictions is not naturalistic. The god sits with his heels together, an unnatural stance. He theorized that the posture belonged to a tradition of physical and mental discipline ancestral to yoga.[25]

Ahmed points that the horned figure might be a yogi. But that does not identify him with Shiva, and does not prove he is a god or even a demigod. The "horned hod" may actually be a shaman and his posture associated with communication with animal spirits, divination, or magic healing. He points that modern Pirs sit in unnatural stances to slip into a trance. That does not make them yogis or gods. The traditional shoemakers of Pakistan also sit in stances similar to the posture of the "horned god".[25]

The Rigveda has the related pashupa "protector of cattle" as a name of Pushan. The Pashupatinath Temple is the most important Hindu shrine for all Hindus in Nepal and also for many Hindus in India and rest of the world.

Vedic god of fire, Agni is sometimes depicted as a horned deity.

Horns mentioned in the bible

The Canaanite gods Baal and El were likely originally horned bull gods as may have been Yahweh.[26]:15[27]:28

"I will cut off the horns of all the wicked, but the horns of the righteous will be lifted up."

In majesty he (Jacob) is like a firstborn bull; his horns are the horns of a wild ox. With them he will gore the nations, even those at the ends of the earth.

Then I saw a second beast, coming out of the earth. It had two horns like a lamb, but it spoke like a dragon.

The priest shall then put some of the blood on the horns of the (Yahweh's) altar of fragrant incense that is before the LORD in the tent of meeting. The rest of the bull’s blood he shall pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering at the entrance to the tent of meeting.

The depiction of a horned Moses stems from the description of Moses' face as "cornuta" ("horned") in the Latin Vulgate translation of the passage from Exodus in which Moses returns to the people after receiving the Ten Commandments for the second time. The Douay–Rheims Bible translates the Vulgate as,"And when Moses came down from the mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord."[32]

Influence on Demonology

Christian demonology

The idea that demons have horns seems to have been taken from the Book of Revelation chapter 13. The book of Revelation seems to have inspired many depictions of demons. This idea has also been associated with the depiction of certain ancient gods like Moloch and the shedu, etc., which were portrayed as bulls, as men with the head of a bull, or wearing bull horns as a crown.

Baphomet of Mendes

The satanic "horned god" symbol known as the baphomet is based on an Egyptian ram deity that was worshipped in Mendes, called Banebdjed (literally Ba of the lord of djed, and titled "the Lord of Mendes"), who was the soul of Osiris. According to Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of ancient Egypt, the book's author Geraldine Harris, said the ram gods Ra-Amun (see: Cult of Ammon), and Banebdjed, were to mystically unite with the queen of Egypt to sire the heir to the throne (a theory based on depictions found in several Theban temples in Mendes).

Occultist Eliphas Levi in his Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (1855), combined the images of the Tarot of Marseilles' Devil card and refigured the ram Banebdjed as a he-goat, calling it the "Baphomet of Mendes," (or, "Goat of Mendes"). The inaccurate description can be traced back to Herodotus' Histories Book II, where Herodotus describes the deity of Mendes as having a goat's head and fleece, when Banebdjedet was really represented by a ram, not a goat.

The Baphomet of Lévi was to become an important figure within the cosmology of Thelema, the mystical system established by Aleister Crowley in the early twentieth century. Baphomet features in the Creed of the Gnostic Catholic Church recited by the congregation in The Gnostic Mass, in the sentence: "And I believe in the Serpent and the Lion, Mystery of Mystery, in His name BAPHOMET" (see: Aleister Crowley: Occult).

Lévi's Baphomet is the source of the later Tarot image of the Devil in the Rider-Waite design. The concept of a downward-pointing pentagram on its forehead was enlarged upon by Lévi in his discussion (without illustration) of the Goat of Mendes arranged within such a pentagram, which he contrasted with the microcosmic man arranged within a similar but upright pentagram. The actual image of a goat in a downward-pointing pentagram first appeared in the 1897 book La Clef de la Magie Noire by Stanislas de Guaita, later adopted as the official symbol—called the Sigil of Baphomet—of the Church of Satan, and continues to be used among Satanists.

Neopaganism

Few neopagan reconstructionist traditions recognize Satan or the Devil outright. However, many neopagan groups worship some sort of Horned God, for example as a consort of the Great Goddess in Wicca. These gods usually reflect mythological figures such as Cernunnos or Pan, and any similarity they may have to the Christian Devil seems to date back only to the 19th century, when a Christian reaction to Pan's growing importance in literature and art resulted in his image being translated to that of the Devil.[33]

Witch-cult hypothesis

In 1985 Classical historian Georg Luck, in his Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, theorised that the origins of the Witch-cult may have appeared in late antiquity as a faith primarily designed to worship the Horned God, stemming from the merging of Cernunnos, a horned god of the Celts, with the Greco-Roman Pan/Faunus,[34] a combination of gods which he posits created a new deity, around which the remaining pagans, those refusing to convert to Christianity, rallied and that this deity provided the prototype for later Christian conceptions of the Devil, and his worshippers were cast by the Church as witches.[34]

Beelzebub

There is an implied connection between Satan and Beelzebub (lit. Lord of the Flies), originally a Semitic deity called Baal (lit. "lord"). Beelzebub is the most recognized demon in the Bible, whose name has become analogous to Satan. Occult and metaphysical author Michelle Belanger believes that Beelzebub (a mockery of the original name[35]) is the horned god Ba'al Hadad, whose cult symbol was the bull.[36] According to The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, Beelzebub reigned over the Witches' Sabbath ("synagoga"[37]), and that witches denied Christ in his name and chanted "Beelzebub" as they danced.[38]

Beelzebub was also imagined to be sowing his influence in Salem, Massachusetts: his name came up repeatedly during the Salem witch trials, the last large-scale public expression of witch hysteria in North America or Europe, and afterwards Rev. Cotton Mather wrote a pamphlet entitled Of Beelzebub and his Plot.[39]

Neopaganism

In 1933, the Egyptologist Margaret Murray published the book, The God of the Witches, in which she theorised that Pan was merely one form of a horned god who was worshipped across Europe by a witch-cult.[40] This theory influenced the Neopagan notion of the Horned God, as an archetype of male virility and sexuality. In Wicca, the archetype of the Horned God is highly important, and is thought by believers to be represented by such deities as the Celtic Cernunnos, Indian Pashupati and Greek Pan.

Horned God in Wiccan based neopagan religions represents a solar god often associated with vegetation, that's honored as the Holly King or Oak King in Neopagan rituals.[41] Most often, the Horned God is considered a male fertility god.[42] The use of horns as a symbol for power dates back to the ancient world. From ancient Egypt and the Ba'al worshipping Cannanites, to the Greeks, Romans, Celts, and various other cultures.[43] Horns have ever been present in religious imagery as symbols of fertility and power.[44][45] It was not until Christianity attributed horns to Satan as part of his iconography that horned gods became associated with evil in Western mythology:[46]

Many modern neo-Pagans focus their worship on a horned god, or often "the" Horned God and one or more goddesses. Deities such as Pan and Dionysus have had attributes of their worship imported into the Neopagan concept as have the Celtic Cernunnos and Gwynn ap Nudd, one of the mythological leaders of the Wild Hunt[47][48][49][50]

See also

Sources

- Ahmed, Mukhtar (2014), "The World of Gods and Goddesses", Ancient Pakistan-An Archaeological History:Volume IV: Harappan Civilization -Theoretical and the Abstract, Foursome Group, ISBN 978-1496082084

References

- 1 2 Handbook of Egyptian mythology, Geraldine Pinch, p 114-115, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-517024-5

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece ix.16 § 1

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece iii.18 § 2

- ↑ Jerem. xlvi.25

- ↑ Oric Bates, The Eastern Libyans.

- ↑ Mohammed Chafik, revue Tifinagh...

- ↑ H. Basset, Les influences puniques chez les Berbères, pp 367-368

- ↑ Mohammed Chafik, Revue Tifinagh...

- ↑ Helene Hagan, The Shining Ones: An Etymological Essay on the Amazigh Roots of the Egyptian civilization, p. 42.

- ↑ James Hastings.

- ↑ "Coin: from the Persian Wars to Alexander the Great, 490–336 bc". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- ↑ Green 2007. p.382

- ↑ Plutarch, Alexander, 27

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Alexander III, 1971

- ↑ Green, Miranda J. Animals in Celtic Life and Myth. pp. 227–228

- ↑ Green, Miranda J. Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art. p. 112.

- ↑ Malcolm Todd, A Companion to Roman Britain, P. 209

- ↑ Witches: true encounters with wicca, wizards, covens, cults, and magick by Hans Holzer Page 125

- ↑ http://www.livius.org/am-ao/ammon/ammon.html

- ↑ Vernantius Emeka Ndukaihe, Achievement as Value in the Igbo/African Identity: The Ethics LIT Verlag, 2007 ISBN 3-8258-9929-2

- ↑ Flood (1996), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ For translation of paśupati as "Lord of Animals" see: Michaels, p. 312.

- ↑ For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1 in: Flood (1996), p. 29.

- 1 2 Ahmed (2014), p. 182-183

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Ahmed (2014), p. 190-197

- ↑ Susan Niditch. Oral World and Written Word: Ancient Israelite Literature. Westminster John Knox Press, Jan 1, 1996 ISBN 9780664227241

- ↑ Stephen C. Russell. Images of Egypt in Early Biblical Literature: Cisjordan-Israelite, Transjordan-Israelite, and Judahite Portrayals (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, 403) De Gruyter; 1 edition (November 16, 2009) ISBN 9783110221718

- ↑ Online Bible Gateway -Psalm 75:10

- ↑ Online Bible Gateway -Deuteronomy 33:17

- ↑ Online Bible Gateway -Revelation 13:11

- ↑ Online Bible Gateway -Leviticus 4:7

- ↑ Ruth Mellinkoff. The Horned Moses in Medieval Art and Thought (California Studies in the History of Art, 14). University of California Press; First Edition (June 1970) ISBN 0520017056

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (1999). Triumph of the Moon. Oxford: Oxford UniverUniversity Press. p. 46.

- 1 2 Luck, Georg (1985). Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑ The Dictionary of Demons: Names of the Damned By Michelle Belanger -Page 56

- ↑ Witch hunts in the western world: persecution and punishment from the ... Page 87 - by Brian Alexander Pavlac

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca by Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. 97

- ↑ Of Beelzebub and his Plot

- ↑ The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Ronald Hutton, page 199

- ↑ The Legend of the Holly King and the Oak King By Patti Wigington

- ↑ The Quest: A Search for the Grail of Immortality by Rhuddlwm Gawr pg. 210

- ↑ Myth and Territory in the Spartan Mediterranean by Irad Malkin pg. 159

- ↑ Wicca: The Complete Craft by Deanna J. Conway pg. 54

- ↑ The Language of God in the Universe by Helena Lehman pg. 301

- ↑ The Devil: perceptions of evil from antiquity to primitive Christianity by Jeffrey Burton Russell pg. 245

- ↑ Fabulous creatures, mythical monsters, and animal power symbols: a handbook by Cassandra Eason pg. 107

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism By Shelley Rabinovitch, James Lewis pg. 133

- ↑ The Oxford companion to world mythology by David Adams Leeming pg. 360

- ↑ The outer temple of witchcraft: circles, spells, and rituals by Christopher Penczak pg. 73