Hormizd IV

| Hormizd IV | |

|---|---|

| Great King (Shah) of Ērānshahr | |

Coin of Hormizd IV, found at Karakhodja, Chinese Central Asia. | |

| Reign | 579–590 CE |

| Predecessor | Khosrau I |

| Successor | Khosrau II |

| Born |

ca. 540 Ctesiphon |

| Died |

590 Ctesiphon |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Khosrau I |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Hormizd IV (Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭬𐭦𐭣; New Persian: هرمز چهارم), was king of the Sasanian Empire from 579 to 590.[1] He was the son and successor of Khosrau I.

Family

Hormizd IV is called a Torkzad in the Shahnameh, meaning son of Turk, according to some sources his mother was the daughter of the Turkish khaqan, this, however, has been rejected by Encyclopædia Iranica, which states that the marriage with the daughter of the Turkish khaqan is impossible, and says that Hormizd was born in 540, thirty years before Khosrau's marriage.[2]

Policies

Khosrau I had appointed Hormizd IV as his heir since he was aware that Hormizd had showed himself as qualified leader.[2] Hormizd IV came to the throne in 579, he seems to have been imperious and violent, but not without some kindness of heart. Some very characteristic stories are told of him by Al-Tabari.[3] His father's sympathies had been with the nobles and the priests. Hormizd IV protected the common people and introduced a severe discipline in his army and court.

When the priests demanded a persecution of the Christians, he declined on the ground that the throne and the government could only be safe if it gained the goodwill of both concurring religions. The consequence was that Hormizd IV raised a strong opposition in the ruling classes, which led to many executions and confiscations. Which even included the famous Karenid vizier of his father, Bozorgmehr,[4] including the latter's brother Simah-i Burzin; the Mihranid Izadgushasp; the spahbed Bahram-i Mah Adhar, and the Ispahbudhan Shapur, who was the father of Vistahm and Vinduyih. According to Al-Tabari, Hormizd is said to have ordered the death of 13,600 nobles and religious members.[5] When Bacurius III of Iberia died in 580, Hormizd IV quickly took the opportunity and replaced the monarchy in Iberia with a Sasanian governor. The reason for this was because the native rulers of Iberia had caused much trouble to the Sasanians.[6]

War against the Byzantines

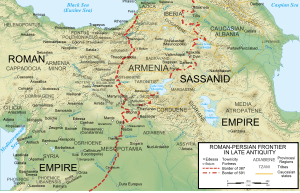

From his father, Hormizd had inherited an ongoing war against the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire and against the Turks in the east. Negotiations of peace had just begun with the Emperor Tiberius II, but Hormizd IV haughtily declined to cede anything of the conquests of his father. Therefore the accounts given of him by the Byzantine authors, Theophylact Simocatta (iii.16 ff), Menander Protector and John of Ephesus (vi.22), who give a full account of these negotiations, are far from favourable.

Determined to teach the Sasanian king a lesson, the Roman General Maurice crossed the frontier and invaded Kurdistan. The next year, he even planned to penetrate into Media and Southern Mesopotamia but the Ghassanid king al-Mundhir allegedly betrayed the Roman cause by informing Hormizd IV of the Roman Emperor's plans. Maurice was forced to retreat in a hurry, but during the course of his retreat to the Roman frontier, he drew the Persian general Adarmahan into an engagement and defeated him.

In 582, the Persian general Tamkhosrau crossed the Perso-Roman frontier and attacked Constantina, but was defeated and killed. However, the deteriorating physical condition of the Roman Emperor Tiberius II forced Maurice to return to Constantinople immediately. Meanwhile John Mystacon, who had replaced Maurice, attacked the Persians at the junction of the Nymphius and the Tigris but was defeated and forced to withdraw. Another defeat brought about his replacement by Philippicus.

Philippicus spent the years 584 and 585 making deep incursions into Persian territory.[7] The Persians retaliated by attacking Monocartium and Martyropolis in 585. Philippicus inflicted a heavy defeat on them at Solachon in 586 and besieged the fortress of Chlomaron. After an unsuccessful siege, Philippicus retreated and made a stand at Amida. Soon, however, he relinquished command to Heraclius in 587.

In the year 588, the Roman troops mutinied and taking advantage of this mutiny, Persian troops once again attacked Constantina but were repulsed. The Romans retaliated with an equally unsuccessful invasion of Arzanene, but defeated another Persian offensive at Martyropolis.

In 589, the Persians attacked Martyropolis and captured it after defeating Philippicus twice. Philippicus was recalled and was replaced by Comentiolus under whose command the Romans defeated the Persians at Sisauranon. The Romans now laid siege to Martyropolis but at the height of the siege news circulated in Persia about a Turkish invasion.

War in the East

In 588, the Sasanian Empire was in chaos; The Arabs had started pillaging the western provinces, while the Khazars ravaged the northern provinces, and now the Turks had occupied Balkh and were penetrating into the heart of Persia. Hormizd IV, under the advice of Nastuh, called upon father of the latter, who was named Mihransitad. According to Ferdowsi, Mihransitad told the Sasanian king that the astrologers had predicted that a certain Bahram Chobin would be the savior of Iran. He then suggested that Bahram Chobin should be summoned to the Sasanian court. The aged Mihransitad is said to have immediately died after that.[8]

Hormizd did as he advised and finally dispatched a contingent under the general Bahram Chobin to fight them back. Bahram marched upon Balkh and defeated the Turks killing their Khan and capturing his son.

Soon after the threat from the north was exterminated, Bahram was sent to fight the Khazars on the northern frontier, where he was successful. He was then sent to fight the Romans on the northern frontier, where he was initially successful, raiding in Svaneti as well as warding off both Caucasian Iberian and Roman offensives against Caucasian Albania, but was defeated by the Roman general Romanus in a subsequent battle on the river Araxes.

Hormizd, jealous of the rising fame of Bahram, disgraced him, and had him removed from the Sasanian office. Hormizd also wished to humiliate him and sent him a complete set of women's garments to wear. Bahram responded by writing him an extremely offensive letter. Enraged, Hormizd sent Persian soldiers to arrest Bahram but they moved over to Bahram's side. Bahram, with a large army, then marched towards the capital, Ctesiphon.[9]

Overthrow and death

After hearing about Bahram's rebellion, Hormizd tried to organize an effective resistance against him by trying to sideline with Vistahm and Vinduyih along with other Sasanian nobles, but was dissuaded, according to Sebeos, by his son, Khosrau II. Hormizd responded by having Vinduyih and many other nobles imprisoned, but Vistahm apparently managed to flee; soon after, however, the two brothers appear as the leaders of a palace coup that deposed, blinded and killed Hormizd, raising his son Khosrau to the throne.[10]

References

- ↑ Beate Dignas, Engelbert Winter, Rome and Persia in late antiquity: neighbours and rivals, (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 42.

- 1 2 SASANIAN DYNASTY – Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Theodor Nöldeke, Geschichte d. Perser und Araber unter den Sasaniden, 264 ff.

- ↑ Khaleghi Motlagh, Djalal (1990). "BOZORGMEHR-E BOḴTAGĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 4.

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), p. 118

- ↑ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation: 2nd edition, p. 23. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3

- ↑ Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-521-32591-9.

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), p. 124

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), pp. 122ff.

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), pp. 127–128, 131–132

Sources

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2004). "HORMOZD IV". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 466–467.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Hormizd IV | ||

| Preceded by Khosrau I |

Great King (Shah) of Ērānshahr 579–590 |

Succeeded by Khosrau II |

| ||||||||||