Horace-Bénédict de Saussure

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (17 February 1740 – 22 January 1799) was a Swiss geologist, physicist and Alpine traveller, often considered the founder of alpinism, and considered to be the first person to build a successful solar oven.

Life and work

Horace Bénédicte de Saussure was born the 17 February 1740 in Conches, near Geneva, and died the 22 January 1799 in his hometown.

Saussure was born in a patrician family of Geneva. His father Nicolas de Saussure was an agricultural author who may have sparked his early interest for botany. After attending the "Collège" of his hometown, he completed his studies at the Geneva Academy in 1759 with a dissertation on heat (Dissertatio physica de igne). In 1760, he made the first of his numerous trips to Chamonix, for the purpose of collecting plant specimens for Albrecht von Haller. He offered a reward to the first man to reach the summit of Mont Blanc, at the time unscaled. Inspired by his uncle Charles Bonnet, the young Saussure also worked on the physiology of plants and published Observations sur l'écorce des feuilles et des pétales (1762). The same year, at 22, he was elected professor of philosophy at the Academy of Geneva, where he lectured in Latin on physics, logics and metaphysics in alternate years. He would teach in this academic context until 1786, occasionnally introducing his audience to geography, geology, chemistry and even astronomy.

His early interest in botanical studies and glaciers[1] soon led Saussure to undertake other journeys across the Alps. In 1767, he completed his first tour of the Mont-Blanc, a trip that did much to clear up the topography of the snowy portions of the Alps of Savoy. He also carried out experiments on heat and cold, on the weight of the atmosphere and on electricity and magnetism. For this, he devised what became one of the first electrometers. Other trips led him to Italy, where he examined the Etna and other volcanoes (1772–73),[2] and to the extinct volcanoes of Auvergne.[3]

Although a patrician, Saussure held liberal views that induced him to present in 1774 a plan for a development of scientific education in the Geneva College, which would be open to all citizens, but this attempt was rejected. He was more successful in advocating the creation of the "Société des Arts" (1776), inspired by the London Society for the Improvement of Arts.

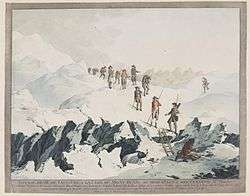

Since 1774 Saussure tried to find a way to reach the summit of Mont-Blanc on the Italian side, accompanied by the Courmayeur alpine guide Jean-Laurent Jordaney on the Miage glacier and on Mont Crammont.[4] In 1776 he ascended the Buet (3,096 m). In 1774 he had mounted the Crammont, and again in 1778, in which year he also explored the Valsorey glacier, near the Great St Bernard. In 1780 he climbed the Roche Michel, above the Mont Cenis Pass. In 1785, he made an unsuccessful attempt on Mont-Blanc, by the Aiguille du Goûter route. Two Chamonix men, Michel Paccard and Jacques Balmat attained the summit in 1786, by way of the Grands Mulets, and in 1787 Saussure himself made the third ascent of the mountain. His achievements did much to attract the attention of tourists to a spot like Chamonix.

Obsessed by the measurement of meteorological phenomena, Saussure invented and improved many kinds of apparatus, including the magnetometer, the cyanometer for estimating the blueness of the sky, the diaphanometer for judging of the clearness of the atmosphere, the anemometer and the mountain eudiometer. Above all he devised a hair hygrometer, and used it for a series of investigations on the phenomena of atmospheric humidity, evaporation, clouds, fogs and rain (Essais sur l'Hygrométrie, 1783). This instrument sparked a bitter controversy with Jean-André Deluc, himself inventor of a whalebone hygrometer.[5]

In 1788 he spent 17 days making meteorological observations and physical measurements on the Col du Géant (3,371 m).

In 1789 he climbed the Pizzo Bianco near Macugnaga, to observe the east wall of Monte Rosa, and crossed the Theodulpass (3,322 m) to Zermatt, which he was the first traveler to visit. On that occasion he climbed from the pass up the Klein Matterhorn (3,883 m), while in 1792 he spent three days making observations on the same pass without descending to Zermatt, and then visited the Theodulhorn (3,472 m).

All his observations and experiments were summed up into seven Alpine journeys published in four quarto volumes, under the general title of Voyages dans les Alpes from 1779 to 1796 (There was an octavo issue in eight volumes, issued from 1780 to 1796). The non-scientific portions of the work were first published in 1834, and often since, as Partie pittoresque des ouvrages de M. de Saussure.

Significance

The Alps formed the centre of Saussure's investigations. He saw them as the grand key to the true theory of the earth, and they gave him the opportunity for studying geology in a manner never previously attempted.[6] The inclination of the strata, the nature of the rocks, the fossils and the minerals received close attention.

He acquired a thorough knowledge of the chemistry of the day; and he applied it to the study of minerals, water and air. Saussure's geological observations made him a firm believer in the Neptunian theory: he regarded all rocks and minerals as deposited from aqueous solution or suspension, and attached much importance to the study of meteorological conditions. His work with rocks, erosion, and fossils would also lead him to the idea that the earth was much older than generally thought and formed part of the basis of Darwin's Theory of Evolution.[7]

He carried barometers and boiling-point thermometers to the summits of the highest mountains, and estimated the relative humidity of the atmosphere at different heights, its temperature, the strength of solar radiation, the composition of air and its transparency. Then, following the precipitated moisture, he investigated the temperature of the earth at all depths to which he could drive his thermometer staves, the course, conditions and temperature of streams, rivers, glaciers and lakes, even of the sea.

His modifications of the thermometer adapted that instrument to many purposes: for ascertaining the temperature of the air he used one with a fine bulb hung in the shade or whirled by a string, the latter form being converted into an evaporimeter by inserting its bulb into a piece of wet sponge and making it revolve in a circle of known radius, at a known rate; for experiments on the earth and in deep water he employed large thermometers wrapped in non-conducting coatings so as to render them extremely sluggish, and capable of long retaining the temperature once they had attained it.

With these instruments he showed that the bottom water of deep lakes is uniformly cold at all seasons, and that the annual heat wave takes six months to penetrate to a depth of 30 ft. in the earth. He recognized the immense advantages to meteorology of high-level observing stations, and whenever it was practicable he arranged for simultaneous observations being made at different altitudes for as long periods as possible.

Saussure was particularly influential as a geologist,[8] and although his ideas on the underlying principles were often erroneous, he was instrumental in greatly advancing that science. He was an early user of the term "geology"—see the "Discours préliminaire" to volume I of his Voyages, published in 1779—though by no means its inventor as some have claimed, the English word having been used in the 1680s and its Latin counterpart "geologia" during the previous several centuries.

He constructed the first known Western solar oven in 1767, trying several designs before determining that a well-insulated box with three layers of glass to trap outgoing thermal radiation created the most heat.[9] The highest temperature he reached was 230 °F, which he found did not vary significantly when the box was carried from the top of Mt. Cramont in the Swiss Alps down to the Plains of Cournier, 4,852 feet below in altitude and 34 °F above in temperature, thereby establishing that the external air temperature played no significant role in this solar heating effect.[10]

In 1784, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

De Saussure died in Geneva in 1799.

Recognition

The genus of high alpine plants Saussurea, some adapted to growing in some of the most extreme high alpine climates tolerated by any plant, is named after him. The Alpine Botanical Garden Saussurea, located at Pavillon du Mont Fréty, first station for the Mont Blanc cable car, in Courmayeur, Aosta Valley, is named after it.

His work as a mineralogist was also recognized. Saussurite is named after him.

De Saussure was honoured by being depicted on the 20 Swiss franc banknote of the sixth issue of Swiss National Bank notes (1979–1995 when replaced by the eighth issue, and the notes were recalled in 2000) (These notes will become valueless on 1 May 2020).

His son Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure was a noted specialist in plant chemistry.

His daughter Albertine Necker de Saussure was a pioneer in the education of women.

Trivia

In his On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, whilst discussing how reason affects our perception of distance, Arthur Schopenhauer includes an anecdote that "Saussure is reported to have seen so large a moon, when it rose over Mont Blanc, that he did not recognize it and fainted with terror".

Notes

- ↑ Albert V. Carozzi & John K. Newman, "Horace-Bénédict de Saussure: Forerunner in glaciology", Mémoires de la SPHN, vol. 48, 1995

- ↑ Daniela Vaj, "Saussure à la découverte de l'Italie (1772-1773)", in René Sigrist (ed.), H.-B. de Saussure (1740-1799). Un regard sur la Terre, Geneva, Georg, 2001, p. 269-299

- ↑ Albert V.Carozzi, Manuscrits et publications de Horace-Bénédict de Saussure sur l’origine du basalte (1772-1797), Geneva, Editions Zoé, 2000

- ↑ Douglas W. Freshfield, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, éd. Slatkine.

- ↑ René Sigrist, "Scientific standards in the 1780s: A controversy over hygrometers", in John Heilbron & René Sigrist (eds), Jean-André Deluc. Historian of Earth and Man, Geneva, Slatkine, 2011, p. 147-183

- ↑ Albert V. Carozzi, "Forty years of thinking in front of the Alps: Saussure's (1796) unpublished theory of the Earth", Earth Sciences History, 8/2, 1989, pp. 123-140

- ↑ "Connections 2" with James Burke, Episode 4 "Whodunit".

- ↑ Marguerite Carozzi, «H.-B. de Saussure: James Hutton's obsession», Archives des Sciences, 53/2, 2000, p. 77-158

- ↑ René Sigrist, Le capteur solaire de Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. Genèse d'une science empirique. Genève, Passé-Présent / Jullien, 1993.

- ↑ Butti, Ken (2004-12-01). "Horace de Saussure and his Hot Boxes of the 1700s". Solar Cooking Archive, Solar Cookers International (Sacramento, California). Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ↑ "Author Query for 'Sauss.'". International Plant Names Index.

References

- Lives by J Senebier (Geneva, 1801), by Cuvier in the Biographie universelle, and by A. P. de Candolle in Décade philosophique

- A.P. Decandolle (1799): XVII. Biographical memoirs of M. de Saussure, Philosophical Magazine Series 1, 4:13, 96-102 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786449908677038

- articles by E. Naville in the Bibliothèque universelle (March, April, May 1883)

- chaps. v.-viii. of Ch. Durier's Le Mont-Blanc (Paris, various editions between 1877 and 1897).

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - René Sigrist, Le capteur solaire de Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. Genèse d'une science empirique. Geneva, Passé-Présent / Jullien, 1993.

- Albert V. Carozzi & Gerda Bouvier, The scientific library of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1797): annotated catalog of an 18th-century bibliographic and historic treasure, Geneva, 1994 (Mémoires de la SPHN, t. 46).

- René Sigrist (ed.), H.-B. de Saussure (1740-1799): un regard sur la terre. Geneva, Georg, 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. |

- Pictures and texts of "Les Voyages dans les Alpes" by H. B. de Saussure can be found in the database VIATIMAGES.

- Horace-Benedict de Saussure and his Hot Boxes of the 1700s

- Horace-Bénédict de Saussure works available online

- (1796-1808) Voyages dans les Alpes, précédés d'un essai sur l'histoire naturelle des environs le Genève, 4 vol. - Linda Hall Library

- (1796) "Agenda, Ou tableau général des observations et des recherches dont les résultats doivent servir de base à la théorie de la terre." Journal des mines, no. 20. Paris, an. 4 (1796); p. 1-70. - Linda Hall Library

|