Hole (band)

| Hole | |

|---|---|

|

Hole performing during a reunion show in Brooklyn, New York, 2012. From left to right: Melissa Auf der Maur, Patty Schemel, Courtney Love, and Eric Erlandson | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1989–2002; 2009–2012 |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

| Past members |

Courtney Love (1989-2002; 2009-2012) Eric Erlandson (1989-2002) Caroline Rue (1989-1992) Lisa Roberts (1989-1990) Mike Geisbrecht (1990) Errol Stewart (1990) Jill Emery (1990-1992) Patty Schemel (1992-1998) Kristen Pfaff (1993-1994) Leslie Hardy(1994) Melissa Auf der Maur (1994-1999) Samantha Maloney (1998-1999) Micko Larkin (2009-2012) Shawn Dailey (2009-2012) Stu Fisher (2009-2012) Scott Lipps (2011-2012) |

Hole was an American alternative rock band that formed in Los Angeles, California in 1989 by singer and guitarist Courtney Love and lead guitarist Eric Erlandson. The band had a revolving line-up of bassists and drummers, their most prolific being drummer Patty Schemel, and bassists Kristen Pfaff (d. 1994) and Melissa Auf der Maur. Over the duration of their career, Hole went on to become one of the most successful female-fronted rock bands of all time, with their studio albums selling over three million records in the United States alone.[1]

Initially prolific in Los Angeles' punk rock scene, the band collaborated with Kim Gordon for their critically acclaimed debut album, Pretty on the Inside (1991), following it with the more commercially viable Live Through This (1994), which was widely acclaimed and reached platinum status within a year of its release. With Love's lyrics explicitly discussing issues of body image, identity, and sexual exploitation, Hole became the most high-profile musical group of the 1990s to discuss feminist issues in their songs, and also gained considerable media coverage due to Love's reckless and disturbing live performances. Their third release, the more polished Celebrity Skin (1998), garnered them four Grammy nominations. In 2002 the group disbanded to pursue other projects.

In 2009, Hole was reformed by Love with new members, despite Erlandson's claim that the reformation breached a mutual contract he had with Love; the reformed band released the album Nobody's Daughter (2010). In 2014, Love confirmed in interviews with BBC and Pitchfork that she was writing new material and that a reunion with the band's previous members had future potential, though the date was indeterminate.

History

Background and formation

Hole formed after Eric Erlandson responded to an advertisement placed by Courtney Love in Recycler in the summer of 1989. The advertisement simply read: "I want to start a band. My influences are Big Black, Sonic Youth, and Fleetwood Mac."[2] "She called me up and talked my ear off," said Erlandson. "We met at this coffee shop, and I saw her and I thought "Oh, God. Oh, no, What am I getting myself into?" She grabbed me and started talking, and she's like "I know you're the right one", and I hadn't even opened my mouth yet."[3] In retrospect, Love said that Erlandson "had a Thurston [Moore] quality about him" and was an "intensely weird, good guitarist."[4] In his 2012 book, Letters to Kurt, Erlandson revealed that he and Love had a sexual relationship during their first year together in the band,[5] which Love also confirmed.[6]

Love had lived a nomadic life prior, immersing herself in numerous music scenes and living in various cities along the west coast. After unsuccessful attempts at forming bands in San Francisco (where she was briefly a member of Faith No More) and Portland, Love relocated to Los Angeles, where she found work as an actress in two Alex Cox films (Sid and Nancy and Straight to Hell). Erlandson was a California native and a graduate of Loyola Marymount University, and was working as a royalties manager for Capitol Records at the time he met Love.[7]

Love had originally wanted to name the band Sweet Baby Crystal Powered by God, but opted for the name Hole instead.[2] During an interview on Later... with Jools Holland, Love claimed the name for the band was inspired by a quote from Euripides' Medea which read "there's a hole that pierces my soul." Additionally, Love cited a conversation with her mother as being the primary inspiration for the band's name: "My mother is this new age psychologist and I said, "I had this terrible childhood", and she said, "You can't have a hole running through you all the time, Courtney.""[8][9] Love also acknowledged the "obvious" genital reference in the band's name, alluding to the vagina, though stated that the primary source of the name was the conversation between her and her mother.[8]

1989–1991: Early work and indie success

In Euripedes' Medea, when she kills the bride and her own child, she says "There's a hole that pierces my soul." [And] my mother's this kind of new age psychologist, and I said "You know, I had this terrible childhood," and she said "Well, you can't have a hole running through you all you time, Courtney." You know, and then [there's] the genital reference, go ahead and make it if you will.

In the months preceding the band's full formation, Love and Erlandson used Michael "Flea" Balzary's rehearsal space in Los Angeles to begin writing during the night;[10] during the day, Love worked as a stripper to support the band and purchase amplifiers and their backline for live shows.[11] Hole's first official rehearsal took place at Fortress Studios in Hollywood with Love, Erlandson and Lisa Roberts on bass. According to Erlandson, "these two girls show up dressed completely crazy, we set up and they said, "okay, just start playing something." I started playing and they started screaming at the top of their lungs for two or three hours. Crazy lyrics and screaming. I said to myself, "most people would just run away from this really fast." But I heard something in Courtney's voice and lyrics."[12] Initially, the band had no percussion until Love met drummer Caroline Rue,[9] and later recruited a third guitarist, Mike Geisbrecht. Hole's first show took place at Raji's, a small bar in Hollywood, in September 1989. By early 1990, Geisbrecht and Roberts had both left the band, which led to the recruitment of bassist Jill Emery.

Hole released their no wave-influenced debut single "Retard Girl" in April 1990, and followed it with "Dicknail" in 1991, released on Sympathy for the Record Industry and Sub Pop, respectively. According to disc jockey Rodney Bingenheimer, Love would often approach him at a Denny's on Sunset Blvd. where he went for coffee in the mornings, and convinced him to give "Retard Girl" airtime on his station KROQ-FM.[13] As the group began to generate income as an underground band, A&R representatives started to appear at their shows. When approached by a label representative who told Love the band needed a more "full sound," she simply replied "fuck off."[4]

In 1991, the band signed onto Caroline Records to release their debut album, and Love sought Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth to produce the record.[14][15] She sent a letter, a Hello Kitty barrette, and copies of the band's early singles to her, mentioning that the band greatly admired Gordon's work and appreciated "... the production of the SST record"[16] (either referring to Sonic Youth's album Sister or EVOL). Gordon, impressed by the band's singles, agreed to produce the album, with assistance from Gumball's Don Fleming. The album, titled Pretty on the Inside, was released in September 1991 to positive reception from underground critics, branded "loud, ugly and deliberately shocking,"[17] and earning a spot on Spin's "20 Best Albums of the Year" list.[18] It was also voted album of the year by New York's Village Voice[19] and peaked at number 59 on the UK albums chart.[20] The album spawned one single, "Teenage Whore", which entered the UK Indie Chart at number one,[21] as well as the band's debut music video for the song "Garbadge Man".

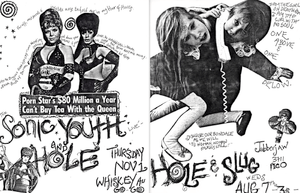

Musically and lyrically, Pretty on the Inside was abrasive and drew on elements of punk rock and sludge metal, characterized by overt noise and feedback, chaotic guitar riffs, contrasting tempos, graphic lyrics, and a variation of Love's vocals ranging from whispers to guttural screaming.[22][23] In later years, Love referred to the album as "unlistenable", despite its critical accolades and eventual cult following.[24][25] The band embarked on a European tour in the fall of 1991 with Mudhoney and Daisy Chainsaw supporting.[26][27] They also toured intermittently in the United States between July and December 1991, playing primarily at hard rock and punk clubs, including CBGB and the Whisky A Go Go, where they opened for The Smashing Pumpkins.[28] In a write-up by the Los Angeles Times on the band's final show of the tour, it was noted that Love smashed the headstock of her Rickenbacker guitar onstage.[28]

1992–1995: Mainstream success; Pfaff's death

Courtney Love and Eric Erlandson began writing new material for a second Hole album in 1992, in the midst of Love's pregnancy with Kurt Cobain. Love's desire to take the band in a more melodic and controlled rock format led bassist Emery to leave the band,[29] and drummer Caroline Rue followed. In an advertisement to find a new bass player, Love wrote: "[I want] someone who can play ok, and stand in front of 30,000 people, take off her shirt and have 'fuck you' written on her tits. If you're not afraid of me and you're not afraid to fucking say it, send a letter. No more pussies, no more fake girls, I want a whore from hell."[16][30] In April 1992, drummer Patty Schemel was recruited after an audition in Los Angeles, but the band spent the rest of the year without a consistent bassist.

Hole signed to Geffen's subsidiary DGC label with an eight-album contract in late 1992. In the spring of 1993, the band released their single "Beautiful Son", which was recorded in Seattle with producer Jack Endino as a fill-in bass player; Love also played bass on the single's b-side "20 Years In the Dakota", as well as on their contribution to the 1993 Germs tribute album A Small Circle of Friends.[31] In the spring of 1993, Love and Erlandson recruited Janitor Joe bassist Kristen Pfaff,[32] and the band toured the United Kingdom in the summer of that year (including the Phoenix Festival on July 16), mainly performing material from their upcoming major label debut, Live Through This, which they recorded at Triclops Studios in Marietta, Georgia in October 1993.

Live Through This released on April 12, 1994, four days after, Kurt Cobain was found dead in his Seattle home. Kurts home was shared with his wife Courtney Love Cobain and his daughter Frances Bean Cobain. His death was surrounded with speculation but Seattle authorities ruled it was a suicide. In the days following the Nirvana frontmans death, his widow refused to discuss her album with the media, and mourned with his fans outside their home. A recording of Mrs. Cobain reading his suicide note to his fans was played at a memorial service in Seattle, where she arrived shortly after the ceremony to distribute some of his clothing to fans. http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/nirvana/articles/story/5937982/inside_the_heart_and_mind_of_nirvana Inside the Heart and Mind of Nirvana]." (April 16, 1992) Rolling Stone</ref> In the wake of Love's family tragedy, Live Through This was a critical success. It spawned several popular singles, including "Doll Parts", "Violet", and "Miss World", going multi-platinum and being hailed "Album of the Year" by Spin magazine.[33][34][35] NME called the album "a personal but secretive thrash-pop opera of urban nihilism and passionate dumb thinks,"[36] and Rolling Stone said the album "may be the most potent blast of female insurgency ever committed to tape."[37]

Despite the critical praise for Live Through This, furious rumors circulated insinuating that Cobain had actually written the majority of the album, though the band vehemently denies this.[29] The band's drummer Patty Schemel, who had been friends with Cobain since the late 1980s,[24] said: "There's that myth that Kurt [Cobain] wrote all our songs— it's not true. Courtney and Eric wrote Live Through This."[29] The band did, however, state that Love convinced Cobain to provide backing vocals on "Asking for It" and "Softer, Softest" while visiting the studio, and music producers and engineers present during the recording sessions noted that Cobain seemed "completely unfamiliar" with the songs.[38] According to Rolling Stone rock journalist Gavin Edwards, Love and Cobain had written songs together in the past, but opted to not release them because it was "a bit too redolent of John and Yoko."[38] Incidentally, Love has revealed that the alternate mix of "Asking for It" featuring Cobain, was planned to be released as a single before his death.

In 1994, bassist Kristen Pfaff went into a drug treatment facility to treat her heroin addiction. Kristen Pfaff contemplated leaving the band due to health reasons. In June 1994, the bassist died of a heroin overdose, Kristen was found dead in the bathroom of her Seattle home. [39] The band put their impending tour on hold, pulling out of the upcoming Lollapalooza festival. Spending the summer out of the media spotlight, Hole recruited bassist Melissa Auf der Maur, and returned to the stage on August 26 at the Reading Festival in England, giving an infamous performance that John Peel described as "teetering on the edge of chaos."[40] The band embarked on a worldwide tour throughout late 1994 and for the duration of 1995, with appearances at the KROQ Almost Acoustic Christmas, Saturday Night Live, the Big Day Out festival, MTV Unplugged, the 1995 Reading Festival, Lollapalooza 1995, and at the MTV Video Music Awards, where they were nominated for the "Doll Parts" music video.[41][42]

Love's reckless stage presence during the tour became a media spectacle, drawing press from MTV and other outlets due to her unpredictable performances.[43][44] While touring with Sonic Youth, Love got into a physical fight with Kathleen Hanna backstage at a 1995 Lollapalooza festival and punched her in the face.[2][45] In an August 1995 band interview with Rolling Stone, drummer Patty Schemel formally came out as a lesbian, saying: "It's important. I'm not out there with that fucking pink flag or anything, but it's good for other people who live somewhere else in some small town who feel freaky about being gay to know that there's other people who are and that it's okay."[3] Toward the end of the tour, the band released their first EP, titled Ask for It, in September 1995; it featured 1991 Peel session recordings, as well as covers of songs by Wipers and The Velvet Underground.

1996–1997: Hiatus

Hole was thought to be on hiatus in 1996 due to Love's rising movie career after she landed a lead role in The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996). Despite the reported hiatus, the band recorded and released a cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Gold Dust Woman" for The Crow: City of Angels (1996) soundtrack, the band's first studio song to feature Melissa Auf der Maur on bass. Hole released two retrospective albums during this time: firstly, their second EP, titled The First Session (1997), which consisted of a complete version of the band's first recording session at Rudy's Rising Star in Los Angeles in March 1990, some of which had been bootlegged widely years prior. It featured the group's first ever recorded track, "Turpentine", which had previously been unreleased to the public.

The same year, the band released their first compilation album, My Body, The Hand Grenade (1997), which was produced chiefly by Erlandson; Love designed the packaging and artwork on the album.[46] The album was conceived as a retrospective on the band's career, featuring early singles, b-sides and recent live tracks.[46][47][48] Although Hole as a band did not perform during 1996 and 1997, members of Hole performed separately, including Love's guest appearance at a Smashing Pumpkins show in February 1996, at which she performed "Silverfuck" and "Farewell and Goodnight", with Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan. Auf der Maur and Schemel also performed a show in Toronto in July 1996. Erlandson collaborated with Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and director Dave Markey in the short-lived project, Rodney & the Tube Tops, with whom he released one single.

1998–2002: Celebrity Skin; disbandment

In 1997, the band entered Conway Recording Studios in Los Angeles after many "fruitless attempts" in Miami, New Orleans, London, and New York to record a follow-up to Live Through This. Hole's third studio album, Celebrity Skin (1998) adopted a complete new sound for the band, incorporating elements of power pop, and Love drawing influence from Fleetwood Mac and My Bloody Valentine.[49] The studio work on Celebrity Skin took almost a year and a half— according to Erlandson, Love was more focused on song-writing and singing than playing guitar. In addition to the band, Billy Corgan entered the studio and helped perfect the songs.[49] Love, who felt she was in a creative slump, referred to Corgan's presence in the studio to "a math teacher who wouldn't give you the answers but was making you solve the problems yourself."[49]

Corgan was credited with co-writing five of the twelve songs on the album, and upon its release made references that he should have "been given credit [for writing the entire album]."[50] Erlandson responded to Corgan's statements in a Rolling Stone interview, commenting: "We were working on all the stuff that Courtney and I had already written. Billy really facilitated things, in a way... I would bring in the music, Courtney would start coming up with lyrics right away, and [Billy] would help map it all out." Erlandson also stated: "Courtney writes all her own lyrics. Nobody else is writing those lyrics and nobody ever has."[51] One journalist took note of the controversy when reviewing the album, stating: "Back in 1994, the acclaim for Live Through This was undercut by whispers that Love's late husband wrote the album. Combine those conspiracy theories with the unfounded but persistent rumor that Cobain was actually murdered, and it is no surprise that, in the song "Celebrity Skin", Love calls herself a walking study in demonology."[50]

Although Schemel is listed as drummer in the liner notes of the record, her drumming does not actually appear on the record; she was replaced by session drummer Deen Castronovo, under pressure from producer Michael Beinhorn.[52] After the replacement, Schemel quit the band.[52][53] Though Love and Erlandson had authorized Schemel's replacement, both expressed regret in retrospect, and Love stated in 2011 that Beinhorn was notorious for replacing drummers on records, and referred to him as "a Nazi".[24] After Schemel's departure, the band hired drummer Samantha Maloney for their upcoming tours and music videos.[53]

Celebrity Skin was a critical success with strong sales and successful singles, including the title track, "Celebrity Skin", "Malibu", and "Awful". The album received unanimously positive reviews, with praise from music periodicals such as Rolling Stone, NME, and Blender,[54][55] as well as a four-star review from the Los Angeles Times,[56] calling it a "wild emotional ride" sure to be "one of the most dissected and debated collections of the year."[56] The album charted incredibly well, peaking at number 9 on the Billboard 200, and garnering the band its first and only number 1 single, "Celebrity Skin", which topped the Modern Rock Tracks. "Malibu" was the album's second successful single, making it to number 3 on the Modern Rock Tracks.

In the winter of 1998–99, Hole went on tour to promote Celebrity Skin, joining Marilyn Manson, who was promoting his album, Mechanical Animals (1998) on the "Beautiful Monsters Tour". The tour turned into a publicity magnet, and Hole dropped out of the tour nine dates in, due to both the majority of the fans being Manson's, and the 50/50 financial arrangement between the groups, with Hole's production costs being disproportionately less than Manson's.[57] Manson and Love often mocked one another onstage, and Love attacked Manson's stage antics, which included tearing up a Bible during performances: "You know, whenever somebody rips up the Bible in front of 40,000 people, I think it's a big deal," she said during a 1999 interview.[13] Hole played one last show on the tour after a poorly received concert at Portland's Rose Garden Arena, which ended with Manson fans booing the band.[58]

The band continued to book shows and headline festivals after dropping off Manson's tour, and according to Auf der Maur, it was a "daily event" for Love to invite audience members onstage to sing with her for the last song at nearly every concert performance.[59] On June 18, 1999 during Hole's set at the Hultsfred Festival in Sweden, a 19-year-old girl died after being crushed by the mosh pit behind the mixing board.[60] Hole played its final show at Thunderbird Stadium in Vancouver on July 14, 1999.

In October 1999, Auf der Maur quit Hole and went on to become a touring bassist for The Smashing Pumpkins. Samantha Maloney also quit a few months later. The band's final release was a single for the movie Any Given Sunday (1999). "Be a Man", released in March 2000, was an outtake from the Celebrity Skin sessions. Love and Erlandson officially disbanded Hole via a message posted on the band's website in 2002.[61] After the split, the four musicians each took on projects of their own. Erlandson continued to work as a producer and session musician, eventually forming the experimental group RRIICCEE with controversial artist, Vincent Gallo and Love began a solo career, releasing her debut, America's Sweetheart in 2004. Melissa Auf der Maur also embarked on a solo career, and released her self-titled debut album in 2004, which also included Erlandson on lead guitar on the track, "Would If I Could." Her second album, Out of Our Minds, was released on March 30, 2010.

Hole's original body of work includes thirteen singles, six Grammy nominations, three LPs, three EPs, one compilation album and 10 music videos.

2009–2013: Reformation and name dispute

On June 17, 2009, NME posted two in-depth blogs, and links to two interviews, of Courtney Love announcing the reunion of Hole.[62] Days later, Melissa Auf der Maur stated in an interview that she was unaware of any reunion, but said Love had asked her to contribute harmonies to an upcoming album.[63] Eric Erlandson stated in Spin magazine that contractually no reunion could take place without his involvement, citing that he and Love "have a contract".[64][65] In a later interview, Erlandson explained how "[Courtney's] management convinced me that it was all hot air and that she would never be able to finish her album. Now I'm left in an uncomfortable position."[66]

Hole launched a new website and various social media pages on January 1, 2010, and performed on Friday Night with Jonathan Ross in February. On February 17, 2010 they played a full set at the O2 Shepherds Bush Empire, with support from Little Fish.[67] On March 16, the first Hole single in ten years, was released, titled "Skinny Little Bitch", debuting at No. 32 on Billboard's Alternative Singles Chart and receiving airplay on Active rock and alternative radio.

Nobody's Daughter was released on April 26, 2010 worldwide on Mercury Records, and was received by music critics with moderately positive acclaim.[68] Rolling Stone gave the album three out of five stars, but noted "[while Love] was an absolute monster vocalist in the nineties, the greatest era ever for rock singers... She doesn't have that power in her lungs anymore – barely a trace. But at least she remembers, and that means something in itself." The magazine also referred to the album as "not a true success", but a "noble effort".[69] Love's voice, which had been noticeably raspier (likely due to years of scream-singing, drug abuse, and smoking) was compared to the likes of Bob Dylan.[70] NME gave the album a 6/10 rating, and Robert Christgau rated it an "A-", saying, "Thing is, I can use some new punk rage in my life, and unless you're a fan of Goldman Sachs and BP Petroleum, so can you. What's more, better it come from a 45-year-old woman who knows how to throw her weight around than from the zitty newbies and tattooed road dogs who churn most of it out these days. I know—for her, BP Petroleum is just something else to pretend about. But the emotion fueling her pretense is cathartic nevertheless."[71] In support of the release, Hole toured extensively between 2010 and 2012 throughout North America and Europe, as well as performing in Japan, Russia, and Brazil.

On March 28, 2011, Love, Erlandson, Patty Schemel and Auf der Maur appeared at the New York screening of Schemel's documentary Hit So Hard: The Life and Near-Death Story of Patty Schemel at the Museum of Modern Art.[72] The appearance was the first time in thirteen years that all four members appeared together in public. Schemel had expressed a desire to record with Love, Erlandson and Auf der Maur stating "nothing has been discussed, but I have a feeling."[72] After the screening, the four took part in a Q&A session where Love stated: "For me, as much as I love playing with Patty – and I would play with her in five seconds again, and everyone onstage – if it's not moving forward, I don't wanna do it. That's just my thing. There's rumblings; there's always bloody rumblings. But if it's not miserable and it's going forward and I'm happy with it… that's all I have to say about that question."[73]

In May 2011, a music video for "Samantha" was shot in Istanbul, although it remained officially unreleased.[74] In September 2011, Scott Lipps joined the band, replacing drummer Stu Fisher. In April 2012, Love, Erlandson, Auf der Maur and Schemel reunited at the Public Assembly in New York for a two-song set, including "Miss World" and the Wipers' "Over the Edge," at an after-party for the Hit So Hard documentary.[75] The performance marked the first time the four members performed together live since 1995.

On December 29, 2012, Love performed a solo acoustic set in New York City, and in January 2013, performed at the Sundance Film Festival under her own name.[76] She booked further performances across North America as a solo act, with Larkin, Dailey, and Lipps as her backing band.[77]

2014–2015: Retrospective

On December 28, 2013, Love posted two photos of herself with Erlandson on Facebook and Twitter, with a caption reading: "And this just happened… 2014 going to be a very interesting year."[78] Love also tagged Melissa Auf der Maur as well as Hole's former manager, Peter Mensch, in the post, alluding to a reconciliation with Erlandson and possible reunion in 2014.[79][80]

On April 2, 2014, Rolling Stone reported that the Celebrity Skin line-up of the band had reunited (with Patty Schemel in lieu of Samantha Maloney).[81] Rolling Stone erroneously reported Love's upcoming solo single, "Wedding Day" to be a product of this reunion. Shortly after, Love curtailed her statement, saying: "We may have made out but there is no talk of marriage. It’s very frail, nothing might happen, and now the band are all flipping out on me."[82] On May 1, in an interview with Pitchfork, Love discussed the possibility of a reunion, and also stated it had been "a mistake" releasing Nobody's Daughter as a Hole record in 2010. "Eric was right—I kind of cheapened the name, even though I'm legally allowed to use it. I should save "Hole" for the lineup everybody wants to see and had the balls to put Nobody's Daughter under my own name."[83][84][85] Love further discussed the possibility of reuniting the band, saying:

No one's been dormant. Patty teaches drumming and drums in three indie bands. Melissa has her metal-nerd thing going on—her dream is to play Castle Donington with Dokken. Eric hasn't flipped—I jammed with him, he's still doing his Thurston [Moore]-crazy tunings, still corresponding with Kevin Shields. We all get along great. There are bands who reunite and hate each others' guts.[83]

In an interview with the September 2014 issue of Paper, Love stated that a reunion of the band in 2015 was likely.[86]

In another interview with Billy Koepe, of www.PunkGlobe.com, Eric stated that "I've also been doing research for a Hole box set that I'd like to finish as soon as possible. I have tapes galore that need to be digitized. I may have to do the dreaded "kickstarter" campaign to get it all done. It's not easy listening back to old Hole rehearsals. Lemme tellya. The screaming, the anguish, the F-C-G chords over and over again like some sick folk loop." [87]

Musical style

Initially, Hole drew inspiration from no wave and experimental bands, which is evident in their earliest recordings, specifically "Retard Girl", but frontwoman Love also drew from a variety of influences. Love, who had grown up in Portland, was influenced by local punk band Wipers, UK post-punk groups such as Echo and the Bunnymen and Joy Division, and classic rock such as Neil Young and Fleetwood Mac.[88] The band's first album, Pretty on the Inside, was heavily influenced by noise and punk rock, using discordant melodies, distortion, and feedback, with Love's vocals ranging from whispers to guttural screams. Love described the band's earliest songwriting as being based on "really crazy Sonic Youth tunings."[89] Nonetheless, Love claimed to have aimed for a pop sound early on: "There's a part of me that wants to have a grindcore band and another that wants to have a Raspberries-type pop band,"[90] she told Flipside magazine in 1991. Both Love and Erlandson were fans of the notorious LA punk band The Germs.[91] In a 1996 interview for a Germs tribute documentary, Erlandson said: "I think every band is based on one song, and our band was based on "Forming"... Courtney brought it into rehearsal, and she knew, like, three chords and it was the only punk rock song we could play."[91]

The band's second album Live Through This, captured a less abrasive sound, while maintaining the group's original punk roots. "I want this record to be shocking to the people who don't think we have a soft edge, and at the same time, [to know] that we haven't lost our very, very hard edge,"[92] Love told VH1 in 1994. The group's third album, Celebrity Skin, incorporated power pop into their hard rock sound, and was heavily inspired by California bands; Love was also influenced by Fleetwood Mac and My Bloody Valentine while writing the album.[49][93] The group's 2010 release, Nobody's Daughter, featured a more folk rock-oriented sound, utilizing acoustic guitar and softer melodies.

The group's chord progressions by and large drew on elements of punk music,[94] which Love described as "grungey", although not necessarily grunge.[95] Critics described their song style as "deceptively wispy and strummy,"[94] combined with "gunshot guitar choruses."[96] Although the group's sound changed over the course of their career, the dynamic between beauty and ugliness has often been noted, particularly due to the layering of harsh and abrasive riffs which often bury more sophisticated arrangements.[97]

Songwriting

Love once said that lyrics were "the most important thing" to her when writing music.[9] Her songwriting dealt with a variety of themes throughout Hole's career, including body image, rape, child abuse, addiction, celebrity, suicide, elitism, and inferiority complex; all of which were addressed mainly from a female, and often feminist standpoint.[98] This underlying feminism in Love's lyrics often led the public and critics to mistakenly associate her with the riot grrrl movement, of which Love was highly critical.[99][100][100][101]

In a 1991 interview with Everett True, Love said: "I try to place [beautiful imagery] next to fucked up imagery, because that's how I view things... I sometimes feel that no one's taken the time to write about certain things in rock, that there's a certain female point of view that's never been given space."[102] Charles Cross has referred to her lyrics on Live Through This as being "true extensions of her diary,"[29] and she has admitted that a great deal of the lyrics from Pretty on the Inside were excisions from her journals.[89]

Throughout Hole's career, Love's lyrics were often referential to other works of art and literature: Pretty on the Inside contains references to The Ballad of East and West by Rudyard Kipling;[103] the title of the band's album Live Through This (as well as lyrics from the track "Asking for It") is directly drawn from Gone With the Wind;[104] and the group's single "Celebrity Skin" (the title track to their 1998 album), contains quotes from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice and Dante Rossetti's poem A Superscription.[105][106] Love had had a minor background in literature, having briefly studied English literature in her early twenties.[107]

Live performances

Throughout the duration of the 1990s, the band received widespread media coverage due to Love's often rambunctious and unpredictable behavior onstage. The band often destroyed equipment and guitars at the end of concerts,[108] and Love would ramble between songs, bring fans onstage, and stage dive, sometimes returning with her clothes torn off of her or sustaining injuries.[109] Nina Gordon of Veruca Salt, who toured with Hole in 1995, recalled Love's erratic behavior onstage, saying "She would just go off and [the rest of the band] would just kind of stand there."[24] The majority of Love's chaotic behavior onstage was a result of heavy drug use at the time, which she admitted: "I was completely high on dope; I cannot remember much about it."[24][110] She later admonished her behavior during that time, saying: "I [saw] pictures of how I looked. It's disgusting. I'm ashamed. There's death and there's disease and there's misery and there's giving up your soul... The human spirit mixed with certain powders is not the person, it's [a] demonic presence."[111]

Love's onstage attire also garnered notoriety, later being dubbed the title "kinderwhore", which consisted of tattered babydoll dresses and smeared makeup.[112][113] Kurt Loder likened her onstage attire to a "debauched ragdoll",[114] and John Peel noted in his review of the band's 1994 Reading Festival performance, that "[Love], swaying wildly and with lipstick smeared on her face, hands and, I think, her back, as well as on the collar of her dress, [...] would have drawn whistles of astonishment in Bedlam. The band teetered on the edge of chaos, generating a tension which I cannot remember having felt before from any stage."[40] Rolling Stone referred to the style as "a slightly more politically charged version of grunge; apathy turned into ruinous angst, which soon became high fashion's favorite pose."[115]

The band's set lists for live shows were often loose, featuring improvisational jams and rough performances of unreleased songs. By 1998, their live performances had become less aggressive and more restrained, although Love continued to bring fans onstage, and would often go into the crowd while singing.[59]

Cultural impact

Hole went on to become the most commercially successful female-fronted rock band in history, selling over 3 million records in the United States alone during their initial career.[116][1][117] In spite of Love's often polarizing reputation in the media, Hole received consistent critical praise for their output, and was often noted for the predominant feminist commentary found in Love's lyrics, which scholars have credited as "articulating a third-wave feminist consciousness".[118] Love's subversive onstage persona and public image coincided with the band's songs, which expressed "pain, sorrow, and anger, but [an] underlying message of survival, particularly survival in the face of overwhelming circumstances."[119] Music journalist Maria Raha expressed a similar sentiment in regard to the band's significance to third-wave feminism, stating, "Whether you love Courtney [Love] or hate her, Hole was the highest-profile female-fronted band of the '90s to openly and directly sing about feminism."[110][120][121]

While Rolling Stone compared the effect of Love's marriage to Cobain on the band to that of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, they noted that "Love's confrontational stage presence, as well as her gut-wrenching vocals and powerful punk-pop songcraft, made her an alternative-rock star in her own right."[122] Author Nick Wise made a similar comparison in discussion of the band's public image, stating, "Not since Yoko Ono's marriage to John Lennon has a woman's personal life and exploits within the rock arena been so analyzed and dissected."[120]

The band has been cited as a major influence on several contemporary artists, including indie singer-songwriter Scout Niblett,[123] Brody Dalle (of The Distillers and Spinnerette),[124] Sky Ferreira,[125] Lana Del Rey,[126] Tove Lo,[127] and the British rock band Nine Black Alps.[128] The band ranked at #77 of VH1's 100 Greatest Hard Rock Artists.[129]

Band members

|

|

Timeline

Discography

- Pretty on the Inside (1991)

- Live Through This (1994)

- Celebrity Skin (1998)

- Nobody's Daughter (2010)

Awards and nominations

| Year | Recipient/Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Celebrity Skin[130] | Best Rock Album | Nominated |

| 1999 | "Celebrity Skin"[130] | Best Rock Song | Nominated |

| 1999 | "Celebrity Skin"[130] | Best Rock Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| 2000 | "Malibu"[131] | Best Rock Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| Year | Recipient/Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | "Doll Parts"[132] | Best Alternative Video | Nominated |

| 1999 | "Malibu"[133] | Best Cinematography | Nominated |

References

- 1 2 Harding, Cortney (April 2, 2010). "Courtney Love: Fixing a Hole". Billboard. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Brite, Poppy Z. Courtney Love: The Real Story. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684845067.

- 1 2 Cohen, Jason (August 24, 1995). "Hole: Life in a Band with Courtney Love, Rock's Wildest Diva". Rolling Stone. p. 66. (re-published in The '90s: The Inside Stories from the Decade That Rocked by Rolling Stone LLC)

- 1 2 Halperin, Ian. Who Killed Kurt Cobain?. Citadel Press. pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Erlandson, Eric. Letters to Kurt. Akashic Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-61775-083-0.

My girlfriend and bandmate at the time, Courtney Love, and I were introduced to him in the parking lot after a Butthole Surfers show at the Hollywood Palladium [...] We had kept our relationship a secret. Courtney did not want our band to lose its sex appeal. She believed that couple bands were too unavailable. The fact was, for more than a year, we had shared a deep and powerful, if codependent, bond.

- ↑ Shapiro, Dave (March 8, 2012). "Courtney Love Is Not Gonna Be Happy About New Cobain Book". Fuse. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

I wish [Eric] well. Even more than Dave [Grohl] and [Krist] Novoselic, Eric was family… I just hope he didn't write that we dated. We had sex, yes, but I don't date.

- ↑ Mason, Darryl (1995). "Hole: A New Lease of Life". The West Australian (January).

- 1 2 3 Love, Courtney (1995). "Courtney Love and Hole". Later... with Jools Holland. London, United Kingdom.

- 1 2 3 Love, Courtney (1995). "Flipside Interview from issue No. 68, September/October 1990". The First Session (Media notes). Hole. Sympathy for the Record Industry, Flipside Magazine.

- ↑ Love, Courtney (May 30, 2013). Interview with Anthony Cumia and Greg Hughes (radio). Interview with Cumia, Anthony, and Greg Hughes. The Opie & Anthony Show. New York City.

Without insulting one of my oldest friends who let me use his rehearsal space before I even had a band, therefore I wouldn't even be here without Flea...

- ↑ "The First Time With... Courtney Love". BBC Radio 6. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ↑ Erlandson, Eric (1999). "Skin Tight". Guitar World (January 1999).

- 1 2 "Courtney Love". The E! True Hollywood Story. October 5, 2003. E!.

- ↑ Cracked, George (April 2002). "The Noise Rock: F.A.Q.". Monochrom: Cracked Webzine. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Pretty on the Inside". CD Universe. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- 1 2 Love, Courtney. Dirty Blonde: The Diaries of Courtney Love. Faber & Faber, Inc.

- ↑ Q Magazine Review: Pretty on the Inside by Hole (1991-10). p. 138

- ↑ Spencer, Lauren (December 17, 1991). "20 Best Albums of the Year". SPIN. p. 122.

- ↑ Strong, Martin Charles; John Peel. The Great Rock Discography. Canongate Books. p. 696. ISBN 1-84195-551-5.

- ↑ "Hole". The Official Charts Company. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Indie Charts: September 28, 1991". The ITV Chart Show. September 28, 1991. Channel 4.

- ↑ Anderson, Kyle. Accidental Revolution: The Story of Grunge. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312358198.

- ↑ Loder, Kurt (March 21, 2004). "Courtney Love, Grievous Angel: The Interview With Kurt Loder". MTV. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cooper, Leonie (March 24, 2011). "10 Things We Learn About Kurt Cobain And Courtney Love From Hit So Hard". NME. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Pretty on the Inside LP". InSound. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Des Barres, Pamela (March 1994). "Rock and Roll Needs Courtney Love". Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ↑ Love, Courtney; France, Kim (June 3, 1996). "Led by Alanis Morissette and Courtney Love, a whole new breed of feminism is standing atop the pop cultural heap". New York Magazine (June 1996): 41. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- 1 2 Cromelin, Richard (December 19, 1991). "POP MUSIC REVIEW : Pumpkins, Hole Unleash Frustrations". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Courtney Love". Behind the Music. June 21, 2010. Vh1.

- ↑ Meltzer, Marisa (2010-02-02). Girl Power: The Nineties Revolution in Music. Faber & Faber. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-86547-979-1.

- ↑ "A Small Circle of Friends: A Germs Tribute: Various Artists". Allmusic. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Janitor Joe". AllMusic. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Live Through This". Tower Records. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Live Through This review". NME: 22. December 24, 1994. Ranked No. 12 in NME's list of the `Top 50 Albums Of 1994.'

- ↑ "''Live Through This'' Q Review". Tower.com. May 7, 2005. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Live Through This: Review". NME: 40. 1994-04-09.

- ↑ Fricke, David (1994-12-29). "Live Through This". Rolling Stone: 191.

- 1 2 Edwards, Gavin (2006). Is Tiny Dancer Really Elton’s Little John?: Music’s Most Enduring Mysteries, Myths, and Rumors Revealed. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-34603-2.

- ↑ Kery Murakami (July 12, 1994). "Hole Bassist Died Of Drug Overdose". Seattle Times. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- 1 2 Peel, John (August 30, 1994). "Hole at Reading". The Guardian.

- ↑ "1995 MTV Video Music Awards". MTV. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ Masley, Ed. "10 Most Memorable Moments of the MTV Music Video Awards". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Snow, Shauna (August 2, 1995). "Hole Performance Disrupted". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Courtney Love and Hole". Weekly World News: 12. October 3, 1995.

- ↑ Bowie, Chas (January 9, 2006). "Raising America's Sweetheart: An Interview with Courtney Love's Mother". Portland Mercury. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Liner notes, My Body, The Hand Grenade (1997). City Slang Records

- ↑ Tyrangiel, Josh (November 13, 2006). "The All-Time 100 Albums: Live Through This". Time Magazine. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ↑ Love, Courtney. Extracts from an interview with Melody Maker, 1997-10.

- 1 2 3 4 The Interview (CD). Hole. Geffen. 1998. PRO-CD-1232.

- 1 2 "Hole flaunts survival with polished Celebrity Skin". CNN. September 4, 1998. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ Schwartz, Jennifer (October 8, 1998). "Hole's Eric Erlandson Sheds His Celebrity Skin". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- 1 2 Don Zulaica (2005-08-05). "Lived Through That: Patty Schemel - DRUM! Magazine". DRUM! Magazine Online. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- 1 2 Hit So Hard (2011) Documentary. Well Go USA (DVD).

- ↑ "Hole : Celebrity Skin – Album Reviews". NME. August 4, 1998. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Hunter, Tim (September 1, 1998). "Celebrity Skin by Hole". Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- 1 2 Hilburn, Robert (September 6, 1998). "Love Adds Glow To 'Skin'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ↑ "MTV Interview (1991)". Youtube. November 9, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Ryan, Joal (March 9, 1999). "Courtney Love Lost in Portland". E! Online. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- 1 2 "Music On... Photography by Melissa Auf der Maur: Courtney Love in Crowd Onstage". National Geographic. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Aftonbladet nyheter: Här dog 19-åringen". Aftonbladet.se. June 19, 1999. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Hole at AllMusic.com". AllMusic. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ "The Return Of Hole – Courtney Love's In-The-Studio Video Diary – In The NME Office – NME.COM – The world's fastest music news service, music videos, interviews, photos and free stuff to win". NME. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Melissa Auf Der Maur Says Hole "Reunion" Not Really a Reunion". June 23, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Q&A: Hole's Eric Erlandson". Spin. Retrieved August 2009.

- ↑ "Courtney Love Denies Name Change". Spinner. April 22, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ Brett Buchanan. "GrungeReport.net » Blog Archive » GRUNGEREPORT.NET EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH ERIC ERLANDSON". Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Wednesday February 17, 2010". LastFM. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Pop & Hiss". Los Angeles Times. April 27, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Sheffield, Rob (April 26, 2010). "Rolling Stone review: Nobody's Daughter". Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Petrusich, Amanda (April 27, 2010). "Nobody's Daughter". Pitchfork. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Robert Christgau: CG: Hole". Robert Christgau. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- 1 2 "Hole Reunites For Drummer Patty Schemel's Documentary Premiere | Billboard.com". Billboard. March 28, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Love, Courtney. Extracts from a questions and answers session at the screening of Hit So Hard: The Life and Near Death Story of Patty Schemel at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Rubenstein, Jenna Halley (September 20, 2011). "New Video: Hole, 'Samantha'". MTV. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ↑ Maura Johnston (April 14, 2012). "So, The Mid-'90s Lineup of Hole (Including Courtney Love) Reunited At Public Assembly Last Night – New York Music – Sound of the City". The Village Voice. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Courtney Love to Perform Live During Sundance". Yahoo! Finance. January 13, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Courtney Love puts ad on Craigslist for new bassist – and gets just one response". New Musical Express. May 29, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Melissa Locker (December 30, 2013). "Courtney Love Drops Hints That A Hole Reunion Might Be Coming In 2014". Time Magazine. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ Stacey Anderson (December 30, 2013). "Is Courtney Love Reuniting Hole?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Courtney Love Teases 2014 Hole Reunion, Promises 'Interesting' Year". Spin. December 30, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Kory Grow (April 2, 2014). "Courtney Love to Reunite Hole's 'Celebrity Skin' Lineup Again". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ↑ McCormick, Neil. "Courtney Love interview: 'There will be no jazz hands on Smells Like Teen Spirit'". The Telegraph. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 Pelly, Jenn (May 1, 2015). "Interviews: Courtney Love". Pitchfork. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Love, Courtney (April 1, 2014). Woman's Hour, Courtney Love; game changing politics; Lauren Owen. Interview with Jane Garvey. British Broadcasting Company. BBC. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ↑ Ben Beaumont-Thomas (April 3, 2014). "Courtney Love reforms classic Hole line-up". The Guardian. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ↑ Scordelis, Alex (2014). "Courtney Love Brings Anarchy to Hollywood". Paper Magazine. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ↑ http://punkglobe.com/ericerlandsoninterview0615.php

- ↑ Pretty on the Inside features a re-write of the riff from Young's "Cinnamon Girl", as well as sampling from "Rhiannon" by Fleetwood Mac.

- 1 2 Hole interviewed at Big Day Out tour. Interview with Ground Zero. 1999.

- ↑ "Flipside Interview from issue #68, September/October 1990". The First Session (Media notes). Hole. Sympathy for the Record Industry, Flipside Magazine. 1995.

- 1 2 "Erlandson, Eric. ''The Germs: A Tribute''. 1996". YouTube. December 3, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Love, Courtney; Patty Schemel. Promotional Interview Segment for Live Through This. MTV Networks. 1994.

- ↑ Hole: Celebrity Skin (songbook). Cherry Lane Music. March 1, 1999. ISBN 978-1575601373.

- 1 2 Weisbard, Eric (September 1999). "The Greatest Albums of the '90s". Spin Magazine. p. 120.

- ↑ Strong, Catherine (2011-11-11). Grunge: Music and Memory. Ashgate. p. 50. ISBN 978-1409423768.

- ↑ Fricke, David (April 21, 1994). "Live Through This by Hole". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ Von Furth, Daisy (October 1991). "Hole Lotta Love". Spin. p. 32.

- ↑ Burns, Lori; Lafrance, Mélisse (2002). Disruptive divas: feminism, identity & popular music. Taylor & Francis, Routledge. pp. 98–103. ISBN 978-0-8153-3554-2.

- ↑ Reilly, Phoebe (October 2005). "Courtney Love: Let the healing begin". Spin: 70–72.

Look, you've got these highly intelligent imperious girls, but who told them it was their undeniable American right not to be offended? Being offended is part of being in the real world. I'm offended every time I see George Bush on TV! And, frankly, it wasn't very good music

- 1 2 Brite, Poppie Z (1998). Courtney Love: The Real Story. Touchstone. p. 117. ISBN 978-0684845067.

She told Melody Maker that she feared Riot Grrrl had become too "teensy weensy, widdle cutie. I think the reason the media is so excited about it is because it's saying females are inept, females are naive, females are innocent, clumsy, bratty... [But] I wore those small dresses [too], and sometimes I regret it.

- ↑ Feigenbaum, Anna (November 2, 2007). Tasker, Yvonne; Negra, Diane, eds. Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Console-ing Passions. Duke University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0822340324.

- ↑ True, Everett (1991-06-15). "Hole in Sidelines". Melody Maker. p. 8.

- ↑ "East is east and west is west" is a famous line from "The Ballad of East and West" by Kipling; this exact phrase is re-used in the track "Mrs. Jones" on Hole's 1991 release, Pretty on the Inside.

- ↑ Love, Courtney. The Return of Courtney Love.

I wrote this song from a monologue in Gone with the Wind, and she says, "I will live through this"— which I already stole,— "and as God as my witness, I will never go hungry again, nor will any of my kin.

- ↑ "With your pound of flesh", a line from the band's 1998 single "Celebrity Skin", is a reference to a request made by Shylock in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice.

- ↑ "My name is might-have-been", a line from the band's 1998 single "Celebrity Skin", is a direct quotation from Dante Rossetti's A Superscription.

- ↑ Kennedy, Dana (August 12, 1994). "The Power of Love". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ↑ Cromelin, Richard (December 19, 1991). "POP MUSIC REVIEWS: Pumpkins, Hole Unleash Frustrations". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

Smashing Pumpkins' singer-guitarist Billy Corgan referred to himself as "a frustrated Midwestern youth" at the Whisky on Tuesday [...] Smashing Pumpkins was preceded by smashing guitars, courtesy of Hole. The tortured, transfixing L.A. group's pairing with the headliners should have made this a bill to remember, but the audience was primed for Pumpkin and didn't take to Courtney Love's powerful howls of anguish. Hole ended its set in a tantrum, as Love ordered the band to halt and hurled her guitar to the ground. Guitarist Eric Erlandson finished things off by demolishing his instrument with a few impressive swings. Frustrated Midwestern youth, meet frustrated California youth.

- ↑ Walters, Barbara (August 1995). Interview with Barbara Walters. Interview with Courtney Love. The Barbara Walters Special. ABC.

- 1 2 Schippers, Mimi A. (2002). Rockin' out of the Box: Gender Maneuvering in Alternative Hard Rock. Rutgers University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8135-3075-8.

- ↑ Love, Courtney (2000), "Hole", Spin, Heroes and Antiheroes (Fifteenth anniversary ed.), p. 92

- ↑ Klaffke, Pamela (2003). Spree: A Cultural History of Shopping. Arsenal Pulp Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-55152-143-5.

- ↑ Baltin, Steve (2010-01-22). "Courtney Love Is Learning to Rein In the 'Courtney Monster'". Spinner. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ↑ Loder, Kurt (April 22, 2008). "Courtney Love Opens Up About Kurt Cobain's Death (The Loder Files)". MTV. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Nika, Colleen. "Courtney Love". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Hole Calls It A Career". Billboard. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ↑ Carson, Mina Julia (ed.). Girls Rock!: Fifty Years of Women Making Music. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0813123103.

- ↑ Morris, Matthew (November 11, 2009). "Writing (Courtney) Love into the History of Rhetoric: Articulation of a Feminist Consciousness in Live Through This" ( PDF (155 KB)). Paper presented at the annual meeting of the NCA 95th Annual Convention, Chicago Hilton & Towers, Chicago, IL.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian G. (2002-11-29). She's a Rebel:The History of Women in Rock & Roll. Seal Press. p. 397.

- 1 2 Lankford, Ronald D. Jr. (November 25, 2009). Women Singer-Songwriters in Rock: A Populist Rebellion in the 1990s. Scarecrow Press. pp. 73–96. ISBN 978-0810872684.

- ↑ Smith, Ethan (July 28, 1995). "Love's Hate Fest". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Hole: Bio". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ↑ Conner, Shawn (August 21, 2013). "Scout Niblett (Interview)". The Snipe News.

I was 17 when I first heard it. I definitely think they had a huge role in that. For me, the thing that I loved about them and her was the anger, and aggressiveness, along with the tender side. That was something I hadn’t seen before in a woman playing music. That was hugely influential and really inspiring. Women up ’til then were kind of one-dimensional, twee, sweet, ethereal, and that annoys the shit out of me.

- ↑ Diehl, Matt. My So-Called Punk. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0312337810.

- ↑ Ferreira, Sky (April 2014). Sky Ferreira for Interview Magazine. Interview with Diehl, Matt. Interview Magazine.

There are a lot of artists that speak to me in the way [Fiona Apple] does. Elliott Smith is one. I also remember when I discovered Hole. I knew Nirvana, and obviously Kurt Cobain was an amazing lyricist, but I remember when I first heard Hole's Live Through This [1994]—like, really listened to it—I was like, "Oh, my god! They get me!"

- ↑ Shine, Matt (June 23, 2014). "Lana Del Rey is Inspired by Courtney Love". Female First. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Moss, Rebecca (April 30, 2014). "Why Swedes Make the Best Breakup Music". Elle. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ↑ Griffiths, Daniel (September 8, 2009). "Quick & Dirty - Nine Black Alps". SoundProof Magazine: 1.

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Hard Rock Artists". Rock On the Net/VH1. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "1999 Grammy Nominees &124; News". NME. November 27, 1998. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ "42nd Annual Grammy Awards List of nominations". CNN. January 4, 2000. Retrieved August 9, 2015. N.B. The categories are listed on page 1 and the artist on page 2.

- ↑ "MTV Video Music Awards | 1995". MTV. Retrieved August 9, 2015. N.B. User must selected "Winners" tab.

- ↑ "Hole Trivia & Quotes". TV.com. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

Bibliography

- Brite, Poppy Z. (1997). Courtney Love: The Real Story. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684845067.

- Burns, Lori; Lafrance, Mélisse (2002). Disruptive divas: feminism, identity & popular music. Taylor & Francis, Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-3554-2.

- Carson, Mina Julia (ed.). Girls Rock!: Fifty Years of Women Making Music. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813123103.

- Diehl, Matt (2007). My So-Called Punk. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312337810.

- Edwards, Gavin (2006). Is Tiny Dancer Really Elton’s Little John?: Music’s Most Enduring Mysteries, Myths, and Rumors Revealed. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-34603-2.

- Erlandson, Eric (2012). Letters to Kurt. Akashic Books. ISBN 978-1-61775-083-0.

- Feigenbaum, Anna (2007). Tasker, Yvonne; Negra, Diane, eds. Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Console-ing Passions. Duke University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0822340324.

- Halperin, Ian (2000). Who Killed Kurt Cobain? The Mysterious Death of an Icon. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0806520742.

- Hole: Celebrity Skin (songbook). Cherry Lane Music. 1999. ISBN 978-1575601373.

- Klaffke, Pamela (2003). Spree: A Cultural History of Shopping. Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 978-1-55152-143-5.

- Lankford, Ronald D. Jr. (2009-11-25). Women Singer-Songwriters in Rock: A Populist Rebellion in the 1990s. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810872684.

- Meltzer, Marisa (2010-02-02). Girl Power: The Nineties Revolution in Music. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-86547-979-1.

- Schippers, Mimi A. (2002). Rockin' out of the Box: Gender Maneuvering in Alternative Hard Rock. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3075-8.

- Strong, Catherine (2011). Grunge: Music and Memory. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409423768.

- Strong, Martin Charles; John Peel. The Great Rock Discography. Canongate Books. ISBN 1-84195-551-5. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hole (band). |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|