De Rham cohomology

In mathematics, de Rham cohomology (after Georges de Rham) is a tool belonging both to algebraic topology and to differential topology, capable of expressing basic topological information about smooth manifolds in a form particularly adapted to computation and the concrete representation of cohomology classes. It is a cohomology theory based on the existence of differential forms with prescribed properties.

Definition

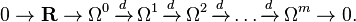

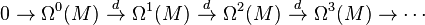

The de Rham complex is the cochain complex of exterior differential forms on some smooth manifold M, with the exterior derivative as the differential.

where Ω0(M) is the space of smooth functions on M, Ω1(M) is the space of 1-forms, and so forth. Forms which are the image of other forms under the exterior derivative, plus the constant 0 function in Ω0(M) are called exact and forms whose exterior derivative is 0 are called closed (see closed and exact differential forms); the relationship d 2 = 0 then says that exact forms are closed.

The converse, however, is not in general true; closed forms need not be exact. A simple but significant case is the 1-form of angle measure on the unit circle, written conventionally as dθ (described at closed and exact differential forms). There is no actual function θ defined on the whole circle of which dθ is the derivative; the increment of 2π in going once round the circle in the positive direction means that we can't take a single-valued θ. We can, however, change the topology by removing just one point.

The idea of de Rham cohomology is to classify the different types of closed forms on a manifold. One performs this classification by saying that two closed forms α, β ∈ Ωk(M) are cohomologous if they differ by an exact form, that is, if α − β is exact. This classification induces an equivalence relation on the space of closed forms in Ωk(M). One then defines the k-th de Rham cohomology group  to be the set of equivalence classes, that is, the set of closed forms in Ωk(M) modulo the exact forms.

to be the set of equivalence classes, that is, the set of closed forms in Ωk(M) modulo the exact forms.

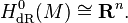

Note that, for any manifold M with n connected components

This follows from the fact that any smooth function on M with zero derivative (i.e. locally constant) is constant on each of the connected components of M.

De Rham cohomology computed

One may often find the general de Rham cohomologies of a manifold using the above fact about the zero cohomology and a Mayer–Vietoris sequence. Another useful fact is that the de Rham cohomology is a homotopy invariant. While the computation is not given, the following are the computed de Rham cohomologies for some common topological objects:

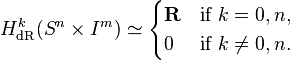

The n-sphere

For the n-sphere, Sn, and also when taken together with a product of open intervals, we have the following. Let n > 0, m ≥ 0, and I an open real interval. Then

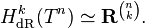

The n-torus

Similarly, allowing n > 0 here, we obtain

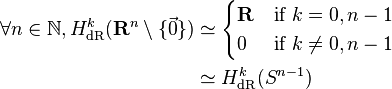

Punctured Euclidean space

Punctured Euclidean space is simply Euclidean space with the origin removed.

The Möbius strip

This follows from the fact that the Möbius strip, M, can be deformation retracted to the 1-sphere:

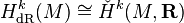

De Rham's theorem

Stokes' theorem is an expression of duality between de Rham cohomology and the homology of chains. It says that the pairing of differential forms and chains, via integration, gives a homomorphism from de Rham cohomology  to singular cohomology groups H k(M; R). De Rham's theorem, proved by Georges de Rham in 1931, states that for a smooth manifold M, this map is in fact an isomorphism.

to singular cohomology groups H k(M; R). De Rham's theorem, proved by Georges de Rham in 1931, states that for a smooth manifold M, this map is in fact an isomorphism.

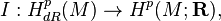

More precisely, consider the map

defined as follows: for any ![[\omega] \in H_{dR}^p(M)](../I/m/0155eb86f50145833b221bf08004ed6c.png) , let I(ω) be the element of

, let I(ω) be the element of  that acts as follows:

that acts as follows:

The theorem of de Rham asserts that this is an isomorphism between de Rham cohomology and singular cohomology.

The wedge product endows the direct sum of these groups with a ring structure. A further result of the theorem is that the two cohomology rings are isomorphic (as graded rings), where the analogous product on singular cohomology is the cup product.

Sheaf-theoretic de Rham isomorphism

The de Rham cohomology is isomorphic to the Čech cohomology H ∗(U, F), where F is the sheaf of abelian groups determined by F(U) = R for all connected open sets U ⊂ M, and for open sets U, V such that U ⊂ V, the group morphism resV,U : F(V) → F(U) is given by the identity map on R, and where U is a good open cover of M (i.e. all the open sets in the open cover U are contractible to a point, and all finite intersections of sets in U are either empty or contractible to a point).

Stated another way, if M is a compact C m+1 manifold of dimension m, then for each k ≤ m, there is an isomorphism

where the left-hand side is the k-th de Rham cohomology group and the right-hand side is the Čech cohomology for the constant sheaf with fibre R.

Proof

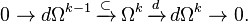

Let Ωk denote the sheaf of germs of k-forms on M (with Ω0 the sheaf of C m+1 functions on M). By the Poincaré lemma, the following sequence of sheaves is exact (in the category of sheaves):

This sequence now breaks up into short exact sequences

Each of these induces a long exact sequence in cohomology. Since the sheaf of C m+1 functions on a manifold admits partitions of unity, the sheaf-cohomology Hi(Ωk) vanishes for i > 0. So the long exact cohomology sequences themselves ultimately separate into a chain of isomorphisms. At one end of the chain is the Čech cohomology and at the other lies the de Rham cohomology.

Related ideas

The de Rham cohomology has inspired many mathematical ideas, including Dolbeault cohomology, Hodge theory, and the Atiyah–Singer index theorem. However, even in more classical contexts, the theorem has inspired a number of developments. Firstly, the Hodge theory proves that there is an isomorphism between the cohomology consisting of harmonic forms and the de Rham cohomology consisting of closed forms modulo exact forms. This relies on an appropriate definition of harmonic forms and of the Hodge theorem. For further details see Hodge theory.

Harmonic forms

If M is a compact Riemannian manifold, then each equivalence class in  contains exactly one harmonic form. That is, every member ω of a given equivalence class of closed forms can be written as

contains exactly one harmonic form. That is, every member ω of a given equivalence class of closed forms can be written as

where α is some form, and γ is harmonic: Δγ = 0.

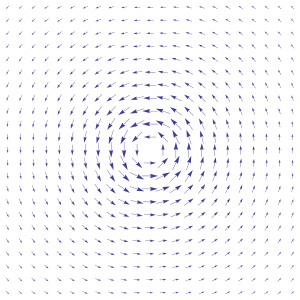

Any harmonic function on a compact connected Riemannian manifold is a constant. Thus, this particular representative element can be understood to be an extremum (a minimum) of all cohomologously equivalent forms on the manifold. For example, on a 2-torus, one may envision a constant 1-form as one where all of the "hair" is combed neatly in the same direction (and all of the "hair" having the same length). In this case, there are two cohomologically distinct combings; all of the others are linear combinations. In particular, this implies that the 1st Betti number of a 2-torus is two. More generally, on an n-dimensional torus Tn, one can consider the various combings of k-forms on the torus. There are n choose k such combings that can be used to form the basis vectors for  ; the k-th Betti number for the de Rham cohomology group for the n-torus is thus n choose k.

; the k-th Betti number for the de Rham cohomology group for the n-torus is thus n choose k.

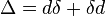

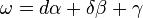

More precisely, for a differential manifold M, one may equip it with some auxiliary Riemannian metric. Then the Laplacian Δ is defined by

with d the exterior derivative and δ the codifferential. The Laplacian is a homogeneous (in grading) linear differential operator acting upon the exterior algebra of differential forms: we can look at its action on each component of degree k separately.

If M is compact and oriented, the dimension of the kernel of the Laplacian acting upon the space of k-forms is then equal (by Hodge theory) to that of the de Rham cohomology group in degree k: the Laplacian picks out a unique harmonic form in each cohomology class of closed forms. In particular, the space of all harmonic k-forms on M is isomorphic to H k(M; R). The dimension of each such space is finite, and is given by the k-th Betti number.

Hodge decomposition

Letting δ be the codifferential, one says that a form ω is co-closed if δω = 0 and co-exact if ω = δα for some form α. The Hodge decomposition states that any k-form can be split into three L2 components:

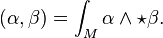

where γ is harmonic: Δγ = 0. This follows by noting that exact and co-exact forms are orthogonal; the orthogonal complement then consists of forms that are both closed and co-closed: that is, of harmonic forms. Here, orthogonality is defined with respect to the L2 inner product on Ωk(M):

A precise definition and proof of the decomposition requires the problem to be formulated on Sobolev spaces. The idea here is that a Sobolev space provides the natural setting for both the idea of square-integrability and the idea of differentiation. This language helps overcome some of the limitations of requiring compact support.

See also

References

- Bott, Raoul; Tu, Loring W. (1982), Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90613-3

- Griffiths, Phillip; Harris, Joseph (1994), Principles of algebraic geometry, Wiley Classics Library, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-05059-9, MR 1288523

- Warner, Frank (1983), Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90894-6

External links

- Idea of the De Rham Cohomology in Mathifold Project

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "De Rham cohomology", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

![H_p(M) \ni [c] \longmapsto \int_c \omega.](../I/m/89f9229a5f32d2962befea5a25f4d6ec.png)