History of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

| Part of a series on |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church |

|---|

|

|

Adventism Seventh-day Adventist portal |

The Seventh-day Adventist Church had its roots in the Millerite movement of the 1830s to the 1840s, during the period of the Second Great Awakening, and was officially founded in 1863. Prominent figures in the early church included Hiram Edson, James Springer White and his wife Ellen G. White, Joseph Bates, and J. N. Andrews. Over the ensuing decades the church expanded from its original base in New England to become an international organization. Significant developments such the reviews initiated by evangelicals Donald Barnhouse and Walter Martin, in the 20th century led to its recognition as a Christian denomination.

Foundations, 1798–1820s

The Second Great Awakening, a revival movement in the United States, took place in the early 19th century. Many religious minority movements formed out of the Congregational, Presbyterian, and the Baptist and Methodist churches. Some of these movements held beliefs that would later be adopted by the Seventh-day Adventists.

An interest in prophecy was kindled among some Protestants groups following the arrest of Pope Pius VI in 1798 by the French General Louis Alexandre Berthier. Forerunners of the Adventist movement believed that this event marked the end of the 1260 day prophecy from the Book of Daniel.[1][2][3] Certain individuals began to look at the 2300 day prophecy found in Daniel 8:14.[1] Interest in prophecy also found its way into the Roman Catholic church when an exiled Jesuit priest by the name of Manuel de Lacunza published a manuscript calling for renewed interest in the Second Coming of Christ. His publication created a stirring but was later condemned by Pope Leo XII in 1824.[1]

As a result of a pursuit for religious freedom, many revivalists had set foot in the United States, aiming to avoid persecution.[4]

Millerite roots, 1831–44

The Seventh-day Adventist Church formed out of the movement known today as the Millerites. In 1831, a Baptist convert, William Miller, was asked by a Baptist to preach in their church and began to preach that the Second Advent of Jesus would occur somewhere between March 1843 and March 1844, based on his interpretation of Daniel 8:14. A following gathered around Miller that included many from the Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian and Christian Connection churches. In the summer of 1844, some of Miller's followers promoted the date of October 22. They linked the cleansing of the sanctuary of Daniel 8:14 with the Jewish Day of Atonement, believed to be October 22 that year. By 1844, over 100,000 people were anticipating what Miller had called the "Blessed Hope". On October 22 many of the believers were up late into the night watching, waiting for Christ to return and found themselves bitterly disappointed when both sunset and midnight passed with their expectations unfulfilled. This event later became known as the Great Disappointment.

Pre-denominational years, 1844–60

Edson and the Heavenly Sanctuary

After the disappointment of October 22 many of Miller's followers were left upset and disillusioned. Most ceased to believe in the imminent return of Jesus. Some believed the date was incorrect. A few believed that the date was right but the event expected was wrong. This latter group developed into the Seventh-day Adventist Church. One of the Adventists, Hiram Edson (1806–1882) wrote "Our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us as I never experienced before. It seemed that the loss of all earthly friends could have been no comparison. We wept, and wept, till the day dawn."[5] On the morning of October 23, Edson, who lived in Port Gibson, New York was passing through his grain field with a friend. He later recounted his experience:

- "We started, and while passing through a large field I was stopped about midway of the field. Heaven seemed opened to my view, and I saw distinctly and clearly that instead of our High Priest coming out of the Most Holy of the heavenly sanctuary to come to this earth on the tenth day of the seventh month, at the end of the 2300 days [calculated to be October 22, 1844], He for the first time entered on that day the second apartment of that sanctuary; and that He had a work to perform in the Most Holy before coming to the earth."[6]

Edson shared his experience with many of the local Adventists who were greatly encouraged by his account. As a result he began studying the bible with two of the other believers in the area, O.R.L. Crosier and Franklin B. Hahn, who published their findings in a paper called Day-Dawn. This paper explored the biblical parable of the Ten Virgins and attempted to explain why the bridegroom had tarried. The article also explored the concept of the day of atonement and what the authors called "our chronology of events".[7][8]

The findings published by Crosier, Hahn and Edson led to a new understanding about the sanctuary in heaven. Their paper explained how there was a sanctuary in heaven, that Christ, the High Priest, was to cleanse. The believers understood this cleansing to be what the 2300 days in Daniel was referring to.[9]

George Knight wrote, "Although originally the smallest of the post-Millerite groups, it came to see itself as the true successor of the once-powerful Millerite movement."[10] This view was endorsed by Ellen White. However, Seeking a Sanctuary sees it more as an offshoot of the Millerite movement.

The "Sabbath and Shut Door" Adventists were disparate, but slowly emerged. Only Joseph Bates had had any prominence in the Millerite movement.[11]

Adventists viewed themselves as heirs of earlier outcast believers such as the Waldenses, Protestant Reformers including the Anabaptists, English and Scottish Puritans, evangelicals of the 18th century including Methodists, Seventh Day Baptists, and others who rejected established church traditions.[12]

Sabbath observance develops and unites

A young Seventh Day Baptist layperson named Rachel Oakes Preston living in New Hampshire was responsible for introducing Sabbath to the Millerite Adventists. Due to her influence, Frederick Wheeler, a local Methodist-Adventist preacher, began keeping the seventh day as Sabbath, probably in the early spring of 1844. Several members of the Washington, New Hampshire church he occasionally ministered to also followed his decision. These included William and Cyrus Farnsworth. T. M. Preble soon accepted it either from Wheeler or directly from Oakes. These events were shortly followed by the Great Disappointment.

Preble promoted Sabbath through the February 28, 1845 issue of the Hope of Israel. In March he published his Sabbath views in tract form. Although he returned to observing Sunday in the next few years, his writing convinced Joseph Bates and J. N. Andrews. These men in turn convinced James and Ellen White, as well as Hiram Edson and hundreds of others.[13]

Bates proposed that a meeting should be organised between the believers in New Hampshire and Port Gibson. At this meeting, which occurred sometime in 1846 at Edson's farm, Edson and other Port Gibson believers readily accepted Sabbath and at the same time forged an alliance with Bates and two other folk from New Hampshire who later became very influential in the Adventist church, James and Ellen G. White. Between April 1848, and December 1850 twenty-two "Sabbath conferences" were held in New York and New England. These meetings were often seen as opportunities for leaders such as James White, Joseph Bates, Stephen Pierce and Hiram Edson to discuss and reach conclusions about doctrinal issues.[14]

While initially it was believed that Sabbath started at 6 pm, by 1855 it was generally accepted that Sabbath begins at Friday sunset.[15]

The Present Truth (see below) was largely devoted to Sabbath at first. J. N. Andrews was the first Adventist to write a book-length defense of Sabbath, first published in 1861.

Trinitarianism

At the formation of the church in the 19th century, many of the Adventist leaders held to an antitrinitarian view. Ellen G. White never entered into debate on this issue. One study, however, sees early Adventism as well as Ellen White to espouse a materialist rather than an Arian theology.[16]

In 1876, James White compared Seventh-day Adventist doctrine with Seventh Day Baptists. He observed: "The principal difference between the two bodies is the immortality question. The S. D. Adventists hold the divinity of Christ so nearly with the trinitarian, that we apprehend no trial here..."[17]

Post-tribulation Premillennialism

Beginning with William Miller's teachings, Adventists have played a key role in introducing the Bible doctrine of premillennialism in the United States. They believe the saints will be received or gathered by Christ into the Kingdom of God in heaven at the end of the Tribulation at the Second Comingbefore the millennium. In the appendix to his book "Kingdom of the Cults" where Walter Martin explains why Seventh-day Adventists are accepted as orthodox Christians (see pg 423) Martin also summarizes the key role that Adventists played in the advancement of premillennialism in the 19th century.

"From the beginning, the Adventists were regarded with grave suspicion by the great majority of evangelical Christians, principally because Seventh-day Adventists were premillennial in their teaching. That is they believed that Christ would come before the millennium...Certain authors of the time considered premillennarians to be peculiar... and dubbed as 'Adventist' all who held that view of eschatology"— "Kingdom of the Cults" p419-420

However the unique contribution of Seventh-day Adventists to this doctrine does not stop there. Seventh-day Adventists are post-tribulation premillennialists who accept the Bible teaching on a literal 1000 years in Revelation 20 that immediately follows the literal second coming of Christ described in Revelation 19. In contrast to almost all premillennialist groups they do not believe in a 1000-year kingdom on earth during the millennium. In Adventist eschatology Christ's promise to take the saints to His Father's house in John 14:1–3 is fulfilled at the 2nd coming where both the living and the dead saints are taken up in the air to meet the Lord (see 1Thess 4:13–18 ). John, the author of Revelation, calls this moment the "first resurrection" in Revelation 20:5–6. Instead of a Millennial Kingdom on earth, Adventists teach that there is only a desolated earth for 1000 years and during that time the saints are in heaven with Christ (See Jeremiah 4:23–29).[18]

Adventist publishing work begins with The Present Truth

On November 18, 1848, Ellen White had a vision in which God told her that her husband should start a paper. In 1849, James, determined to publish this paper, went to find work as a farm-hand to raise sufficient funds. After another vision, she told James that he was to not worry about funds but to set to work on producing the paper to be printed. James readily obeyed, writing from the aid "of a pocket Bible, Cruden's Condensed Concordance, and an abridged dictionary with one of its covers off." Thanks to a generous offer by the printer to delay charges, the group of Advent believers had 1000 copies of the first publication printed. They sent the publication, which was on the topic of Sabbath, to friends and colleagues they believe would find it of interest.[19][20] Eleven issues were published in 1849 and 1850.

Formal organization and further growth, 1860–80

Choosing a name and a constitution

In 1860, the fledgling movement finally settled on the name, Seventh-day Adventist, representative of the church's distinguishing beliefs. Three years later, on May 21, 1863, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists was formed and the movement became an official organization.

Annual regional camp meetings

The first annual regional camp meeting took place September 1868.[21] Since then, the annual regional camp meeting has become a pattern among Seventh-day Adventists and is still practiced today.

Influence of Ellen G. White

Ellen G. White (1827–1915), while holding no official role, was a dominant personality. She, along with her husband, James White, and Joseph Bates, moved the denomination to a concentration on missionary and medical work. Mission and medical work continues to play a central role in the 21st century.

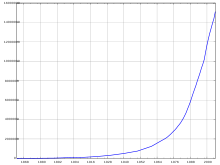

Under White's guidance the denomination in the 1870s turned to missionary work and revivals, tripling its membership to 16,000 by 1880; rapid growth continued, with 75,000 members in 1901. By this time operated two colleges, a medical school, a dozen academies, 27 hospitals, and 13 publishing houses.

By 1945, the church reported 226,000 members in the US and Canada, and 380,000 elsewhere; the budget was $29 million and enrollment in church schools was 40,000.[22] In 1960 there were 1,245,125 members worldwide with an annual budget of over $99,900,000. Enrollment in church schools from elementary to college was 290,000 students.[23] As of the year 2000 there were 11,687,229 members worldwide. The global budget was $28,610,881,313. And the enrollment in schools was 1,065,092 students.[24] In 2008 the global membership was 15,921,408 with a budget of $45,789,067,340. The number of students in SDA run universities, secondary and primary schools was 1,538,607.[25]

Political views

Seventh-day Adventists participated in the Temperance Movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s. During this same time, they became actively involved in promoting Religious Liberty. They had closely followed American politics, matching current events to the predictions in the Bible.

"Seventh-day" means the observance of the original Sabbath, Saturday, is still a sacred obligation. Adventists argued that just as the rest of the Ten Commandments had not been revised, so also the injunction to "remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy" remained in full force. This theological point turned the young group into a powerful force for religious liberty. Growing into its full stature in the late 19th century and early 20th century, these Adventists opposed Sunday laws on every side. Many were arrested for working on Sunday. In fighting against the real threat of a legally established National Day of worship, these Sabbatarians had to fight for their liberty on a daily basis. Soon, they were fighting for religious liberty on a broader, less parochial basis.

Worldwide mission

Adventist effort for a world-wide proclamation of their message began with the mailing of publications. In 1874 J. N. Andrews became the first official Adventist missionary to travel overseas. Working in Switzerland, he sought to organize the Sabbath-keeping companies under one umbrella.[26][27] During the 1890s Adventists began to enthusiastically promote a world-wide mission effort.[28]

A world vision and growing pains, 1880–1915

1888 General Conference

In 1888, a General Conference Session occurred in Minneapolis. This session involved a discussion between the then General Conference president, G. I. Butler; editor of the review, Uriah Smith; and a group led by E. J. Waggoner and A. T. Jones about the meaning of "Righteousness by Faith" and the meaning of the law in Romans and Galatians. Ellen G. White also addressed the conference.

Organizational Developments

From the early 1860s the church had three levels of government: the local church, the conference, and the General Conference. As ideas developed, organizations came into existence to move forward the ideas; i.e. Sabbath Schools, health reform and medical work, printing, distribution of literature, religious liberty, missions, etc. All moved forward under the societies formed to do so.[29] As the work progressed, the managing of all these societies became quite cumbersome.

As conferences developed in far off lands, it became obvious that the General Conference could not oversee the day-to-day needs of the conferences. This led to the development of Union conferences in Australia and Europe in the late 1890s and to the development of districts in the United States.

The 1901 and 1903 General Conference sessions reorganized the church's structure to include union conferences which managed a group of local conferences in their domain. By the end of 1904, the various societal interests became incorporated as departments in each conference's structure.[29]

Christ's Object Lessons and Adventist Schools

Ellen White relates how her book Christ's Object Lessons came to be linked to the financial support of Adventist schools,

"I am so thankful for the work that Christ’s Object Lessons has accomplished and is still accomplishing. When this book was in preparation, I expected to use the means coming from the sale of this book in preparing and publishing several other books. But the Lord put it into my mind to give this book to our schools, to be used in freeing them from debt. I asked our publishing houses to unite with me in this gift by donating the expense of the publication. This they willingly agreed to do. A fund was raised to pay for the materials used in printing the book, and canvassers and people have sold the book without commission.

"Thus the book has been circulated in all parts of the world. It has been received with great favor everywhere. Ministers of all denominations have written testimonials recommending it. The Lord has prepared the way for its reception so that no fewer than 200,000 have already been sold. The means thus raised has gone far toward freeing our schools from the debts that have been accumulating for many years.

"Our publishing houses have printed 300,000 copies, free of cost, and these have been distributed to the different tract societies, to be sold by our people.

"The Lord has made the sale of this book a means of teaching our people how to come in touch with those not of their faith, and how to impart to them a knowledge of the truth for this time. Many have been converted by reading this book."[30]

In 1902, those affiliated with Healdsburg College, now Pacific Union College, dedicated a week to sell Christ's Object Lessons. They first read the book together. Then each student was given six books to sell. Territories were assigned and for a week the school suspended classes in order to sell the books. The College Church took the territory immediately surrounding the church while the students were given territory further away from the school.[31]

Message to the world

After John Andrews venture into Europe, others also went out. Some to Africa, others to Asia and others to Australasia.

Early 20th century, 1915–1930

Fundamentalism and progress

Ellen G. White died in 1915, and Adventist leaders participated in a number of prophetic conferences during and soon after World War I. The 1919 Bible Conference looked at how Adventists interpreted Bible prophecy and the legacy of Ellen White's writings. It also had a polarizing influence on Adventist theology with leaders such as A. G. Daniells and W. W. Prescott questioning some of the traditional views held by others like Benjamin G. Wilkinson, J. S. Washburn, and Claude Holmes.

Fundamentalism was dominant in the church in the early 20th century.[32] George Knight dates it from 1919 to 1950. The edited transcripts of the 1952 Bible Conference were published as Our Firm Foundation.[33]

Mid-20th century

World War II

In Southern Europe, as soon as the war broke out, most of the church's workers of military age were drafted. The church lost union and local conference presidents, pastors, evangelists, and institutional workers.[34]

When the Nazis occupied France they dissolved the conference and all the churches, confiscated church buildings, and prohibited church work. In Croatia all Adventist churches were closed, and the conference was dissolved. All church and evangelistic work was strictly forbidden. Over in Rumania, where there were more than 25,000 Adventists, the union conference, the six local conferences, and all the churches were likewise dissolved. Over three hundred Adventist chapels, the publishing house in Bucharest, and the school at Brasov were all taken from the church. All church funds were taken. Three thousand Adventists were put in prison. They were tortured and abused.[34]

The work of the church went forward under creative cover. People baptized were reported as students graduating and receiving their diplomas. One minister reported on life insurance policies sold. Another reported on the harvest of 253 baskets of fruit.[34]

Late 20th century

In the mid-1970s, two distinct factions were manifest within Seventh day Adventism. Defending many pre-1950 Adventist positions was conservative wing, while the more liberal Adventism emphasized beliefs of Evangelical Christianity.

During the 1970s, what is now the Adventist Review carried articles by editor Kenneth Wood and associate editor Herbert Douglass wrote articles on the Questions on Doctrine issue, and articles arguing for a final perfect generation.[35] Kenneth Wood and Herbert Douglass, editors of the Review and Herald, began to emphasize views which had been the traditional views in the church before Questions on Doctrine such as sinless perfection of a final generation, which was opposed by many Progressive Adventists[36]

The General Conference addressed this controversy over "righteousness by faith" by holding a conference in Palmdale, California in 1976.[35] Ford was the "center of attention", and the resulting document known as the "Palmdale statement"DjVu.[37]

The 1980 General Conference session, held in Dallas, produced the church's first official declaration of beliefs voted by the world body, called the 27 Fundamental Beliefs. (This list of beliefs has since been expanded to the present 28 Fundamentals).

Firing of Desmond Ford

The year 1980 also saw a minor crisis over the investigative judgment teaching, known as the Glacier View controversy. This precipitated a controversy within the church, but the mainstream believe in the doctrine and the church reaffirmed its basic position on the doctrine,[38] although some in the church's more liberal wing continued the controversy into the 21st century.[39] Ford expressed questions on the Judgment and later requested that his membership with the Seventh-day Adventist Church be discontinued for other than doctrinal differences.

Ordination of women

The year 1990 saw ordination of women reviewed at General Conference Session in Indianapolis and 1995 at General Conference Session in Utrecht, but turned down. In 2012 16 women pastors were approved for ordination in the Columbia Union Conference.[40]

Early 21st century

In the new century, Adventists membership continued to increase, and worldwide, members began to use YouTube and other Internet media to communicate. These communications included video addresses from the then-president of the United States George W. Bush, and Hillary Clinton to Adventists.[41]

A review of membership revealed an average of about 2,900 people were joining the Seventh-day Adventist Church every day, which show the denomination now has 16.6 million adult baptized members according to church statistics. Denominational membership showed strong growth and membership audits showed for 2009 as the seventh consecutive year the church had a net gain of more than one million members.[42] However, David Trim, director of the Archives, Statistics and Research department, who felt the numbers were "not entirely accurate," said the record keeping system was not perfect and audits, would most likely result in a lower overall membership number than the 16.5 million.[43]

Spiritual Formation

In the second decade of the 21st century, retired pastor Rick Howard brought what he considered the dangers of Spiritual Formation to the attention of the Adventist church. Other Adventists such as Pastor Hal Mayer, and Derek Morris raised concerns as well. The official church paper, the Adventist Review, published articles[44] outlining the effects of spiritualism coming into the Christian Church through the teachings of Spiritual Formation.[45] Howard wrote The Omega Rebellion in which he warned of the dangers associated with the “emerging church” movement. He identified the teachings of Spiritual formation, contemplative prayer, postmodern spirituality, the meditation steeped in Eastern mysticism as dangerous.[46] In his July 2010 keynote sermon, Ted N.C. Wilson, newly elected President of the Seventh-Day Adventist church counseled, “Stay away from non-biblical spiritual disciplines or methods of spiritual formation that are rooted in mysticism such as contemplative prayer, centering prayer, and the emerging church movement in which they are promoted.” Instead, he said, believers should "look within the Seventh-day Adventist Church, to humble pastors, evangelists, Biblical scholars, leaders, and departmental directors who can provide evangelistic methods and programs that are based on solid Biblical principles and The Great Controversy theme."

Church members were also cautioned to use discernment in worship styles: "Use Christ-centered, Bible-based worship and music practices in church services," Wilson said. "While we understand that worship services and cultures vary throughout the world, don't go backwards into confusing pagan settings where music and worship become so focused on emotion and experience that you lose the central focus on the Word of God. All worship, however simple or complex should do one thing and one thing only: lift up Christ and put down self."[47]

See also

- 28 fundamental beliefs

- The Pillars of Adventism

- Investigative judgment

- List of Seventh-day Adventist colleges and universities

- List of Seventh-day Adventist hospitals

- List of Seventh-day Adventist medical schools

- List of Seventh-day Adventist secondary schools

- William Miller (preacher)

- Millerites

- Premillennialism

- Prophecy in the Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Sabbath in Christianity

- Sabbath in Seventh-day Adventism

- Second coming

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Seventh-day Adventist eschatology

- Seventh-day Adventist interfaith relations – for relations with other Protestants and Catholics

- Seventh-day Adventist theology

- Seventh-day Adventist worship

- Ellen G. White

References

- 1 2 3 Schwarz, Richard W.; Greenleaf, Floyd (2000) [1979]. "The Great Advent Awakening". Light Bearers (Revised ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Department of Education. ISBN 0-8163-1795-X.

- ↑ The Christian Guardian, 1830, Church of England

- ↑ "Prophecy Chart". Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ This information comes from Light Bearers by Schwarz and Greenleaf.

- ↑ Edson, Hiram. manuscript fragment on his "Life and Experience," n.d. Ellen G. White Research Center, James White Library, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Mich. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ F. D. Nichol. The Midnight Cry. p. 458.

- ↑ O. R. L. Crosier (7 February 1846). "The Law of Moses". Day-Star Extra.

- ↑ Howard Krug (2002). "October Morn – Adventism's Day of Insight". Adventist Review.

- ↑ P. Gerard Damsteegt (Fall 1992). "How Our Pioneers Discovered the Sanctuary Doctrine". Adventists Affirm.

- ↑ Adventistreview.org

- ↑ Light Bearers, p 55–56

- ↑ Arthur Patrick, Adventist Studies: An Annotated Introduction for Higher Degree Students

- ↑ material above summarised from Light Bearers to the Remnant

- ↑ Neufield, D (1976). Sabbath Conferences. pp. 1255–1256.

- ↑ White, James (February 25, 1868). "Time to commence the Sabbath" (PDF). Review and Herald (Battle Creek, MI: The Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association) 31 (11): 8. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ↑ Thomas McElwain, Adventism and Ellen White: A Phenomenon of Religious Materialism, Studies on Inter-religious Relations, p. 48, Swedish Science Press, 2010.

- ↑ White, James (October 12, 1876). "The Two Bodies: the relation which the S. D. Baptists and the S. D. Adventists sustain to each other." (PDF). Review and Herald (Battle Creek, Michigan: Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association) 48 (15): 4. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ Adventist.org, Adventist Belief 27

- ↑ "White Estate on Present Truth". Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ "Our Roots and Mission from AR". Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ Spalding, Arthur Whitefield (1949). Captains of the host: First Volume of a History of Seventh-day Adventists Covering the years 1845–1900 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association. pp. 351–362.

- ↑ "Statistical Report of Seventh-day Adventist Conferences, Missions, and Institutions: The Eighty-third Annual Report: Year Ending December 31, 1945." (PDF). General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 1945. p. 24. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Ninety-Eighth Annual Statistical Report of Seventh-day Adventists" (PDF). General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 1960. p. 36. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ "138th Annual Statistical Report—2000" (PDF). General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 2000. p. 66. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ "146th Annual Statistical Report—2008" (PDF). General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 2008. p. 72. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ See Stefan Hoschele, From the End of the World to the Ends of the Earth: The Development of Seventh-day Adventist Missiology (Nurnberg: Verlag fur Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, 2004)

- ↑ "APL Gallery". Retrieved 2006-03-27.

- ↑ Knight, George R. (1999). A Brief History of Seventh-Day Adventists. Adventist Heritage Series (2nd ed.). Review and Herald Publishing Association. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8280-1430-4.

- 1 2 Land, Gary (2005). Historical Dictionary of Seventh-Day Adventists. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-8108-5345-0.

- ↑ MR No. 1188, p. 24 Christ’s Object Lessons to Provide Funds for Schools. part of letter 143, 1902 to Sister Mary

- ↑ M. E. Cady. Christ's Object Lesson at Healdsburg. Pacific Union Recorder, April 10, 1902, p. 14.

- ↑ Historians such as George Knight, Arnold Reye, Lester Devine, Gilbert Valentine and Mark Pearce document its impact

- ↑ Our Firm Foundation, Adventist Archives

- 1 2 3 Olson, A. V. (January 17, 1946). "First Detailed Postwar Report from Southern Europe" (PDF). Review and Herald (Takoma Park, Washington, D. C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association) 123 (3): 1, 17. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- 1 2 "Righteousness by Faith" entry in Historical Dictionary of Seventh-day Adventists by Gary Land

- ↑ Bull, Malcolm & Keith Lochhart, 2006, Seeking a Sanctuary: Seventh-day Adventism and the American Dream, pp.86–87

- ↑ "Christ Our Righteousness" (DjVu). Adventist Review (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald) 153 (22): 4–7. ISSN 0161-1119. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Adventist.org, page 14, 20 for first statistic and original question; p20, 29 for second statistic and original question

- ↑ Dr. Milton Hook (2006). "Sydney Australia Adventist Forum remembers Glacier View twenty-five years later". Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ http://www.columbiaunion.org/article/1165/news/2012-news-archives/november-8-2012-16-female-pastors-approved-for-ordination#.VGVETfnF8nF

- ↑ Goring, Alexis A. (September 1, 2007). "Adventists use YouTube internet videos to share messages". Adventist World, ChurchWorks, World Report. Review and Herald Publishing Association. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ↑ News.Adventist.org

- ↑ Kellner, Mark A. (October 9, 2011). "Adventist Church membership audits planned, revised figures contemplated". Adventist News Network. General Conference Communication Department. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ http://archives.adventistreview.org/article/4614/archives/issue-2011-1522/formed-in-christ

- ↑ http://amazingdiscoveries.org/AD-Magazine-Archive-Summer-2011-Spiritual-Formation

- ↑ http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-omega-rebellion-rick-howard/1029286721?ean=2940014349840

- ↑ http://news.adventist.org/en/archive/articles/2010/07/03/wilson-calls-adventists-to-go-forward

Primary sources

- Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia

- Earliest Seventh-day Adventist Periodicals, reprinted by Andrews University Press. Introduction by George Knight (publisher's page)

- Adventist Classic Library series, reprints of up to 40 major titles by 2015 (publisher's page)

Further reading

- Damsteegt, Gerard. Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist Message & Mission Andrews University Press (publisher's page)

- Edwards, Calvin W. and Gary Land. Seeker After Light: A F Ballenger, Adventism, and American Christianity. (2000). 240pp online review

- Gary Land, ed. Historical Dictionary of Seventh-day Adventists

- Gary Land, ed. Adventism in America: A History, 2nd edition. Andrews University Press (publisher's page)

- Land, Gary (2001). "At the Edges of Holiness: Seventh-Day Adventism Receives the Holy Ghost, 1892–1900". Fides et Historia 33 (2): 13–30.

- London, Samuel G., Jr. Seventh-day Adventists and the Civil Rights Movement (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. x, 194 pp.) ISBN 978-1-60473-272-6

- Morgan, Douglas. Adventism and the American Republic: The Public Involvement of a Major Apocalyptic Movement. (2001). 269 pp. publisher's page, about Adventists and religious freedom

- Morgan, Douglas. "Adventism, Apocalyptic, and the Cause of Liberty," Church History, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Jun. 1994), pp. 235–249 in JSTOR

- Neufield, Don F. ed. Seventh-Day Adventist Encyclopedia (10 vol 1976), official publication

- Pearson, Michael. Millennial Dreams and Moral Dilemmas: Seventh-day Adventism and Contemporary Ethics. (1990, 1998) excerpt and text search, looks at issues of marriage, abortion, homosexuality

- Greenleaf, Floyd (2000). Light Bearers: A History of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (3d ed.). Originally Schwarz, Richard W. (1979). Light Bearers to the Remnant. Official history, and first written by a trained historian.

- Vance, Laura L. Seventh-day Adventism Crisis: Gender and Sectarian Change in an Emerging Religion. (1999). 261 pp.

External links

- Movement of DestinyDjVu by Le Roy Edwin Froom, a classic Adventist work

- October Morn by Howard Krug – a look at Hiram Edson on October 23, 1844

- "Our Roots and Mission" by William G. Johnsson – A history of the Adventist Review

- Seventh-day Adventists: the Heritage Continues

- Adventist Archives Search Historical Documents

- What is Adventist in Adventism? by George R. Knight.

- Prophetic Basis of Adventism by Hans K. La Rondelle.

- Pathways of the Pioneers at the Ellen G. White Estate website

- Arthur Spalding, Captains of the Host (1949), has scholarly credibility

- Articles with subject 'history' as cataloged in the Seventh-day Adventist Periodical Index (SDAPI)

- Adventist History by Michael W. Campbell is a blog about on-going research in Adventist Studies.