History of the Philippines (1521–1898)

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Philippines |

|

| Timeline |

| Philippines portal |

The history of the Philippines from 1521 to 1898, also known as the Spanish Colonial Era, begins with the arrival in 1521 of European explorer Ferdinand Magellan sailing for Spain, which heralded the period when the Philippines was a colony of the Spanish Empire, and ends with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898, which marked the beginning of the American Colonial Era of Philippine history.

Spanish expeditions and colonization

Although the archipelago may have been visited before by the Portuguese (see First Europeans in the Philippines), the earliest documented European expedition to the Philippines was that led by Ferdinand Magellan, in the service of the king of Spain. The expedition first sighted the mountains of Samar at dawn on the 16th March 1521, making landfall the following day at the small, uninhabited island of Homonhon at the mouth of the Leyte Gulf.[1] On Easter Sunday, 31 March 1521, at Limasawa Island, Southern Leyte, as is stated in Pigafetta's Primo Viaggio Intorno El Mondo (First Voyage Around the World), Magellan solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed for the king of Spain possession of the islands he had seen, naming them Archipelago of Saint Lazarus.[2]

Magellan sought alliances among the natives beginning with Datu Zula, the chieftain of Sugbu (now Cebu), and took special pride in converting them to Catholicism. Magellan's expedition got involved in the political rivalries between the Cebuano natives and took part in a battle against Lapu-Lapu, chieftain of Mactan island and a mortal enemy of Datu Zula. At dawn on 27 April 1521, Magellan invaded Mactan Island with 60 armed men and 1,000 Cebuano warriors, but had great difficulty landing his men on the rocky shore. Lapu-Lapu had an army of 1,500 on land. Magellan waded ashore with his soldiers and attacked the Mactan defenders, ordering Datu Zula and his warriors to remain aboard the ships and watch. Magellan seriously underestimated the Lapu-Lapu and his men, and grossly outnumbered, Magellan and 14 of his soldiers were killed. The rest managed to reboard the ships. (See Battle of Mactan)

The battle left the expedition with too few crewmen to man three ships, so they abandoned the "Concepción". The remaining ships - "Trinidad" and "Victoria" – sailed to the Spice Islands in present-day Indonesia. From there, the expedition split into two groups. The Trinidad, commanded by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinoza tried to sail eastward across the Pacific Ocean to the Isthmus of Panama. Disease and shipwreck disrupted Espinoza's voyage and most of the crew died. Survivors of the Trinidad returned to the Spice Islands, where the Portuguese imprisoned them. The Victoria continued sailing westward, commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano, and managed to return to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain in 1522. In 1529, Charles I of Spain relinquished all claims to the Spice Islands to Portugal in the treaty of Zaragoza. However, the treaty did not stop the colonization of the Philippine archipelago from New Spain.[3]

After Magellan's voyage, subsequent expeditions were dispatched to the islands. Four expeditions were sent: that of Loaisa (1525), Cabot (1526), Saavedra (1527), Villalobos (1542), and Legazpi (1564).[4] The Legazpi expedition was the most successful as it resulted in the discovery of the tornaviaje or return trip to Mexico across the Pacific by Andrés de Urdaneta.[5] This discovery started the Manila galleon trade, which lasted two and a half centuries.

In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos named the islands of Leyte and Samar Las Islas Filipinas after Philip II of Spain.[6] Philip II became King of Spain on January 16, 1556, when his father, Charles I of Spain, abdicated the Spanish throne. Philip was in Brussels at the time and his return to Spain was delayed until 1559 because of European politics and wars in northern Europe. Shortly after his return to Spain, Philip ordered an expedition mounted to the Spice Islands, stating that its purpose was "to discover the islands to the west". In reality its task was to conquer the Philippines for Spain.[7]

On November 19 or 20, 1564 a Spanish expedition of a mere 500 men led by Miguel López de Legazpi departed Barra de Navidad, New Spain, arriving off Cebu on February 13, 1565, not landing there due to Cebuano opposition.[8]:77

In 1569, Legazpi transferred to Panay and founded a second settlement on the bank of the Panay River. In 1570, Legazpi sent his grandson, Juan de Salcedo, who had arrived from Mexico in 1567, to Mindoro to punish Moro pirates who had been plundering Panay villages. Salcedo also destroyed forts on the islands of Ilin and Lubang, respectively South and Northwest of Mindoro.[8]:79

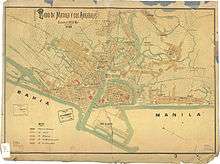

In 1570, Martín de Goiti, having been dispatched by Legazpi to Luzon, conquered the Kingdom of Maynila (now Manila).[8]:79 Legazpi then made Maynila the capital of the Philippines and simplified its spelling to Manila. His expedition also renamed Luzon Nueva Castilla. Legazpi became the country's first governor-general. With time, Cebu's importance fell as power shifted north to Luzon. The archipelago was Spain's outpost in the orient and Manila became the capital of the entire Spanish East Indies. The colony was administered through the Viceroyalty of New Spain (now Mexico) until 1821 when Mexico achieved independence from Spain. After 1821, the colony was governed directly from Spain.

During most of the colonial period, the Philippine economy depended on the Galleon Trade which was inaugurated in 1565 between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico. Trade between Spain and the Philippines was via the Pacific Ocean to Mexico (Manila to Acapulco), and then across the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean to Spain (Veracruz to Cádiz). Manila became the most important center of trade in Asia between the 17th and 18th centuries. All sorts of products from China, Japan, Brunei, the Moluccas and even India were sent to Manila to be sold for silver 8-Real coins which came aboard the galleons from Acapulco. These goods, including silk, porcelain, spices, lacquerware and textile products were then sent to Acapulco and from there to other parts of New Spain, Peru and Europe.

The European population in the archipelago steadily grew although natives remained the majority. They depended on the Galleon Trade for a living. In the later years of the 18th century, Governor-General Basco introduced economic reforms that gave the colony its first significant internal source income from the production of tobacco and other agricultural exports. In this later period, agriculture was finally opened to the European population, which before was reserved only for the natives.

During Spain’s 333 year rule in the Philippines, the colonists had to fight off the Chinese pirates (who lay siege to Manila, the most famous of which was Limahong in 1574), Dutch forces, Portuguese forces, and indigenous revolts. Moros from western Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago also raided the coastal Christian areas of Luzon and the Visayas and occasionally captured men and women to be sold as slaves.

Some Japanese ships visited the Philippines in the 1570s in order to export Japanese silver and import Philippine gold. Later, increasing imports of silver from New World sources resulted in Japanese exports to the Philippines shifting from silver to consumer goods. In the 1580s, the Spanish traders were troubled to some extent by Japanese pirates, but peaceful trading relations were established between the Philippines and Japan by 1590.[9] Japan's kampaku (regent), Toyotomi Hideyoshi, demanded unsuccessfully on several occasions that the Philippines submit to Japan's suzerainty.[10]

On February 8, 1597, King Philip II, near the end of his 42-year reign, issued a Royal Cedula instructing Francisco de Tello de Guzmán, then Governor-General of the Philippines to fulfill the laws of tributes and to provide for restitution of ill-gotten taxes taken from the natives. The decree was published in Manila on August 5, 1598. King Philip died on 13 September, just forty days after the publication of the decree, but his death was not known in the Philippines until middle of 1599, by which time a referendum by which the natives would acknowledge Spanish rule was underway. With the completion of the Philippine referendum of 1599, Spain could be said to have established legitimate sovereignty over the Philippines.[11]

Spanish control

Political system

The Spanish quickly organized their new colony according to their model. The first task was the reduction, or relocation of native inhabitants into settlements. The earliest political system used during the conquista period was the encomienda system, which resembled the feudal system in medieval Europe. The conquistadores, friars and native nobles were granted estates, in exchange for their services to the King, and was given the privilege to collect tribute from its inhabitants. In return, the person granted the encomienda, known as an encomendero, was tasked to provide military protection to the inhabitants, justice and governance. In times of war, the encomendero was duty bound to provide soldiers for the King, in particular, for the complete defense of the colony from invaders such as the Dutch, British and Chinese. The encomienda system was abused by encomenderos and by 1700 was largely replaced by administrative provinces, each headed by an alcalde mayor (provincial governor)[12] The most prominent feature of Spanish cities was the plaza, a central area for town activities such as the fiesta, and where government buildings, the church, a market area and other infrastructures were located. Residential areas lay around the plaza. During the conquista, the first task of colonization was the reduction, or relocation of the indigenous population into settlements surrounding the plaza.

National government

On the national level, the King of Spain, via his Council of the Indies (Consejo de las Indias), governed through his representative in the Philippines, the Governor-General of the Philippines (Gobernador y Capitán General). With the seat of power in Intramuros, Manila, the Governor-General was given several duties: head of the supreme court, the Royal Audiencia of Manila; Commander-in-chief of the army and navy, and the economic planner of the country. All executive power of the local government stemmed from him and as regal patron, he had the authority to supervise mission work and oversee ecclesiastical appointments. His yearly salary was 40,000 pesos. The Governor-General was usually a peninsular Spaniard, a Spaniard born in Spain, to ensure loyalty of the colony to the crown.

Provincial government

On the provincial level, heading the pacified provinces (alcaldia), was the provincial governor (alcalde mayor). The unpacified military zones (corregimiento), such as Mariveles and Mindoro, were headed by the corregidores. City governments (ayuntamientos), were also headed by an alcalde mayor. Alcalde mayors and corregidores exercised multiple prerogatives as judge, inspector of encomiendas, chief of police, tribute collector, capitan-general of the province and even vice-regal patron. His annual salary ranged from P300 to P2000 before 1847 and P1500 to P1600 after it. But this can be augmented through the special privilege of "indulto de commercio" where all people were forced to do business with him. The alcalde mayor was usually an Insulares (Spaniard born in the Philippines). In the 19th century, the Peninsulares began to displace the Insulares which resulted in the political unrests of 1872, notably the execution of GOMBURZA, Novales Revolt and mutiny of the Cavite fort under La Madrid.

Municipal government

The pueblo or town is headed by the Gobernadorcillo or little governor. Among his administrative duties were the preparation of the tribute list (padron), recruitment and distribution of men for draft labor, communal public work and military conscription (quinto), postal clerk and judge in minor civil suits. He intervened in all administrative cases pertaining to his town: lands, justice, finance and the municipal police. His annual salary, however, was only P24 but he was exempted from taxation. Any native or Chinese mestizo, 25 years old, literate in oral or written Spanish and has been a Cabeza de Barangay of 4 years can be a Gobernadorcillo. Among those prominent is Emilio Aguinaldo, a Chinese Mestizo and who was the Gobernadorcillo of Cavite El Viejo (now Kawit). The officials of the pueblo were taken from the Principalía, the noble class of pre-colonial origin. Their names are survived by prominent families in contemporary Philippine society such as Duremdes, Lindo, Tupas, Gatmaitan, Liwanag, Pangilinan, Panganiban, Balderas, and Agbayani, Apalisok, Aguinaldo to name a few.

Barrio government

Every pueblo was further divided into "barrios", and the barrio government (village or district) rested on the barrio administrator (cabeza de barangay). He was responsible for peace and order and recruited men for communal public works. Cabezas should be literate in Spanish and have good moral character and property. Cabezas who served for 25 years were exempted from forced labor. In addition, this is where the sentiment heard as, "Mi Barrio", first came from.

The Residencia and the Visita

To check the abuse of power of royal officials, two ancient castilian institutions were brought to the Philippines. The Residencia, dating back to the 5th century and the Visita differed from the residencia in that it was conducted clandestinely by a visitador-general sent from Spain and might occur anytime within the official’s term, without any previous notice. Visitas may be specific or general.

Maura law

The legal foundation for municipal governments in the country was laid with the promulgation of the Maura Law on May 19, 1893. Named after its author, Don Antonio Maura, the Spanish Minister of Colonies at the time, the law reorganized town governments in the Philippines with the aim of making them more effective and autonomous. This law created the municipal organization that was later adopted, revised, and further strengthened by the American and Filipino governments that succeeded Spanish.

Economy

Manila-Acapulco galleon trade

The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade was the main source of income for the colony during its early years. Service was inaugurated in 1565 and continued into the early 19th century. The Galleon trade brought silver from New Spain, which was used to purchase Asian goods such as silk from China, spices from the Moluccas, lacquerware from Japan and Philippine cotton textiles.[13] These goods were then exported to New Spain and ultimately Europe by way of Manila. Thus, the Philippines earned its income through the trade of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon.

The trade was very prosperous and attracted many merchants to Manila, especially the Chinese. However, initially it neglected the development of the colony's local industries which affected the Indios, since agriculture was their main source of income. In addition, the building and operation of galleons put too much burden on the colonists' annual polo y servicio.

However, it resulted in cultural and commercial exchanges between Asia and the Americas that led to the introduction of new crops and animals to the Philippines such as corn, potato, tomato, cotton and tobacco among others, that gave the colony its first real income. The trade lasted for over two hundred years, and ceased in 1815 just before the secession of American colonies from Spain.

Royal Society of Friends of the Country

José de Basco y Vargas, following a royal order to form a society of intellectuals who can produce new, useful ideas, formally established the Spanish Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country, after the model of the Royal Basque Society. Composed of leading men in business, industry and profession, the society was tasked to explore and exploit the island's natural bounties. The society led to the creation of Plan General Economico of Basco which implemented the monopolies on the areca nut, tobacco, spirited liquors and explosives.

The Society offered local and foreign scholarships and training grants in agriculture and established an academy of design. It was also credited to the carabao ban of 1782, the formation of the silversmiths and gold beaters guild and the construction of the first papermill in the Philippines in 1825. It was introduced on 1780, vanished temporarily on 1787-1819, 1820–1822 and 1875-1822 and ceased to exist in the middle of the 1890s.

Royal Company of the Philippines

On March 10, 1785, King Charles III of Spain confirmed the establishment of the Royal Philippine Company with a 25-year charter.[14] The Basque-based company was granted a monopoly on the importation of Chinese and Indian goods into the Philippines, as well as the shipping of the goods directly to Spain via the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch and British bitterly opposed them because they saw the company as a direct attack on their Asian trade. It also faced the hostility of the traders of the Galleon trade (see above) who saw it as competition. This gradually resulted into the death of both institutions: The Royal Philippine Company in 1814 and the Galleon trade in 1815.[15]

The first vessel of the Royal Philippine Company to set sail was the "Nuestra Señora de los Placeres" commanded by the captain Juan Antonio Zabaleta.[16]

Taxation

Taxation is a system income-generating mechanisms introduced by the Spanish colonial government. Direct taxes are personal tribute and income tax. Indirect taxes are custom duties and the bandala. These are enforced contribution of the people to Spanish government In 1884, the tribute was replaced by cedula personal.

Also there was the bandalâ (from the Tagalog word mandalâ, a round stack of rice stalks to be threshed), an annual forced sale and requisitioning of goods such as rice. Custom duties and income tax were also collected. By 1884, the tribute was replaced by the cedula personal, wherein everyone over 18 were required to pay for personal identification.[17] The local gobernadorcillos were responsible for collection of the tribute. Under the cedula system taxpayers were individually responsible to Spanish authorities for payment of the tax, and were subject to summary arrest for failure to show a cedula receipt.[18]

Aside from paying a tribute, all male Filipinos from 16 to 60 years old were obliged to render forced labor called “polo”. This labor lasted for 40 days a year, later it was reduced to 15 days. It took various forms such as the building and repairing of roads and bridges, construction of Public buildings and churches, cutting timber in the forest, working in shipyards and serving as soldiers in military expeditions. People who rendered the forced labor was called “polistas”. He could be exempted by paying the “falla” which is a sum of money. The polista were according to law, to be given a daily rice ration during their working days which they often did not receive.

Dutch attacks

In 1646, a series of five naval actions known as the Battles of La Naval de Manila was fought between the forces of Spain and the Dutch Republic, as part of the Eighty Years' War. Although the Spanish forces consisted of just two Manila galleons and a galley with crews composed mainly of Filipino volunteers, against three separate Dutch squadrons, totaling eighteen ships, the Dutch squadrons were severely defeated in all fronts by the Spanish-Filipino forces, forcing the Dutch to abandon their plans for an invasion of the Philippines.

On June 6, 1647, Dutch vessels were sighted near Mariveles Island. In spite of the preparations, the Spanish had only one galleon (the San Diego) and two galleys ready to engage the enemy. The Dutch had twelve major vessels.

On June 12, the armada attacked the Spanish port of Cavite. The battle lasted eight hours, and the Spanish believed they had done much damage to the enemy flagship and the other vessels. The Spanish ships were not badly damaged and casualties were low. However, nearly every roof in the Spanish settlement was damaged by cannon fire, which particularly concentrated on the cathedral. On June 19, the armada was split, with six ships sailing for the shipyard of Mindoro and the other six remaining in Manila Bay. The Dutch next attacked Pampanga, where they captured the fortified monastery, taking prisoners and executing almost 200 Filipino defenders. The governor ordered solemn funeral rites for the dead and payments to their widows and orphans.[19][20][21]

There was an expedition the following year that arrived in Jolo in July. The Dutch had formed an alliance with an anti-Spanish king, Salicala. The Spanish garrison on the island was small, but survived a Dutch bombardment. The Dutch finally withdrew, and the Spanish made peace with the Joloans, and then also withdrew.[19][20][21]

There was also an unsuccessful attack on Zamboanga in 1648. That year the Dutch promised the natives of Mindanao that they would return in 1649 with aid in support of a revolt against the Spanish. Several revolts did break out, the most serious being in the village of Lindáo. There most of the Spaniards were killed, and the survivors were forced to flee in a small river boat to Butuán. However, Dutch aid did not materialize. The authorities from Manila issued a general pardon, and many of the Filipinos in the mountains surrendered. However, some of those were hanged and most of the rest were enslaved.[19][20][21]

British invasion

In August 1759, Charles III ascended the Spanish throne. At the time, Britain and France were at war, in what was later called the Seven Years' War. France, suffering a series of setbacks, successfully negotiated a treaty with Spain known as the Family Compact which was signed on 15 August 1761. By an ancillary secret convention, Spain was committed to making preparations for war against Britain.[22]

The early success at Manila did not enable the British to control the Philippines. Spanish-Filipino forces (made up mostly of Filipinos) kept the British confined to Manila. Nevertheless, the British were confident of eventual success after receiving the written surrender of captured Catholic Archbishop Rojo on 30 October 1762.[23]

The surrender was rejected as illegal by Don Simón de Anda y Salazar, who claimed the title of Governor-General under the statutes of the Council of Indies. He led Spanish-Filipino forces that kept the British confined to Manila and sabotaged or crushed British fomented revolts. Anda intercepted and redirected the Manila galleon trade to prevent further captures by the British. The failure of the British to consolidate their position led to troop desertions and a breakdown of command unity which left the British forces paralysed and in an increasingly precarious position.[24]

The Seven Years' War was ended by the Peace of Paris signed on 10 February 1763. At the time of signing the treaty, the signatories were not aware that the Manila was under British occupation and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Crown.[25]

Resistance against Spanish rule

Spanish rule of the Philippines was constantly threatened by indigenous rebellions and invasions from the Dutch, Chinese, Japanese and British.

The previously dominant groups resisted Spanish rule, refusing to pay Spanish taxes and rejecting Spanish excesses. All were defeated by the Spanish and their Filipino allies. In many areas, the Spanish left indigenous groups to administer their own affairs but under Spanish overlordship.

Early resistance

The Resistance against Spain did not immediately cease upon the conquest of the Austronesian cities. After Rajah patis of Cebu, random native nobles resisted Spanish rule. The longest recorded native rebellion was that of Francisco Dagohoy which lasted a century.[26]

During the British occupation of Manila (1762–1764), Diego Silang was appointed by them as governor of Ilocos and after his assassination by fellow natives, his wife Gabriela continued to lead the Ilocanos in the fight against Spanish rule. Resistance against Spanish rule was regional in character, based on ethnolinguistic groups.[27]

Hispanization did not spread to the mountainous center of northern Luzon, nor to the inland communities of Mindanao. The highlanders were more able to resist the Spanish invaders than the lowlanders.

The opening of the Philippines to world trade

In Europe, the Industrial Revolution spread from Great Britain during the period known as the Victorian Age. The industrialization of Europe created great demands for raw materials from the colonies, bringing with it investment and wealth, although this was very unevenly distributed. Governor-General Basco had opened the Philippines to this trade. Previously, the Philippines was seen as a trading post for international trade but in the nineteenth century it was developed both as a source of raw materials and as a market for manufactured goods. The economy of the Philippines rose rapidly and its local industries developed to satisfy the rising demands of an industrializing Europe. A small flow of European immigrants came with the opening of the Suez Canal, which cut the travel time between Europe and the Philippines by half. New ideas about government and society, which the friars and colonial authorities found dangerous, quickly found their way into the Philippines, notably through the Freemasons, who along with others, spread the ideals of the American, French and other revolutions, including Spanish liberalism.

Rise of Filipino nationalism

The development of the Philippines as a source of raw materials and as a market for European manufactures created much local wealth. Many Filipinos prospered. Everyday Filipinos also benefited from the new economy with the rapid increase in demand for labor and availability of business opportunities. Some Europeans immigrated to the Philippines to join the wealth wagon, among them Jacobo Zobel, patriarch of today's Zobel de Ayala family and prominent figure in the rise of Filipino nationalism. Their scions studied in the best universities of Europe where they learned the ideals of liberty from the French and American Revolutions. The new economy gave rise to a new middle class in the Philippines, usually not ethnic Filipinos.

In the early 19th century, the Suez Canal was opened which made the Philippines easier to reach from Spain. The small increase of Peninsulares from the Iberian Peninsula threatened the secularization of the Philippine churches. In state affairs, the Criollos, known locally as Insulares (lit. "islanders"). were displaced from government positions by the Peninsulares, whom the native Insulares regarded as foreigners. The Insulares had become increasingly Filipino and called themselves Los hijos del país (lit. "sons of the country"). Among the early proponents of Filipino nationalism were the Insulares Padre Pedro Peláez, archbishop of Manila, who fought for the secularization of Philippine churches and expulsion of the friars; Padre José Burgos whose execution influenced the national hero José Rizal; and Joaquín Pardo de Tavera who fought for retention of government positions by natives, regardless of race. In retaliation to the rise of Filipino nationalism, the friars called the Indios (possibly referring to Insulares and mestizos as well) indolent and unfit for government and church positions. In response, the Insulares came out with Indios agraviados, a manifesto defending the Filipino against discriminatory remarks. The tension between the Insulares and Peninsulares erupted into the failed revolts of Novales and the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 which resulted to the deportation of prominent Filipino nationalists to the Marianas and Europe who would continue the fight for liberty through the Propaganda Movement. The Cavite Mutiny implicated the priests Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora (see Gomburza) whose executions would influence the subversive activities of the next generation of Filipino nationalists, José Rizal, who then dedicated his novel, El filibusterismo to the these priests.

Rise of Spanish liberalism

After the Liberals won the Spanish Revolution of 1868, Carlos María de la Torre was sent to the Philippines to serve as governor-general (1869–1871). He was one of the most loved governors-general in the Philippines because of the reforms he implemented. At one time, his supporters, including Padre Burgos and Joaquín Pardo de Tavera, serenaded him in front of the Malacañan Palace. Following the Bourbon Restoration in Spain and the removal of the Liberals from power, de la Torre was recalled and replaced by Governor-General Izquierdo who vowed to rule with an iron fist.

Freemasonry

Freemasonry had gained a generous following in Europe and the Americas during the 19th century and found its way to the Philippines. The Western World was quickly changing and sought less political control from the Roman Catholic Church.

The first Filipino Masonic lodge was Revoluccion. It was established by Graciano Lopez Jaena in Barcelona and was recognized in April 1889. It did not last long after he resigned from being its worshipful master on November 29, 1889.

In December 1889, Marcelo H. del Pilar established, with the help of Julio Llorente, the Solidaridad in Madrid. Its first worshipful master was Llorente. A short time later, the Solidaridad grew. Some its members included José Rizal, Pedro Serrano Laktaw, Baldomero Roxas, and Galicano Apacible.

In 1891, Del Pilar sent Laktaw to the Philippines to establish a Masonic lodge. Laktaw established on January 6, 1892, the Nilad, the first Masonic lodge in the Philippines. It is estimated that there were 35 masonic lodges in the Philippines in 1893 of which nine were in Manila. The first Filipina freemason was Rosario Villaruel. Trinidad and Josefa Rizal, Marina Dizon, Romualda Lanuza, Purificacion Leyva, and many others join the masonic lodge.

Freemasonry was important during the time of the Philippine Revolution. It pushed the reform movement and carried out the propaganda work. In the Philippines, many of those who pushed for a revolution were member of freemasonry like Andrés Bonifacio. In fact, the organization used by Bonifacio in establishing the Katipunan was derived from the Masonic society. It may be said that joining masonry was one activity that both the reformists and the Katipuneros shared.

Illustrados, Rizal and Katipunan

The mass deportation of nationalists to the Marianas and Europe in 1872 led to a Filipino expatriate community of reformers in Europe. The community grew with the next generation of Ilustrados studying in European universities. They allied themselves with Spanish liberals, notably Spanish senator Miguel Morayta Sagrario, and founded the newspaper La Solidaridad.

Among the reformers was José Rizal, who wrote two novels while in Europe. His novels were considered the most influential of the Illustrados' writings causing further unrest in the islands, particularly the founding of the Katipunan. A rivalry developed between himself and Marcelo H. del Pilar for the leadership of La Solidaridad and the reform movement in Europe. Majority of the expatriates supported the leadership of del Pilar.

Rizal then returned to the Philippines to organize La Liga Filipina and bring the reform movement to Philippine soil. He was arrested just a few days after founding the league. In 1892, Radical members of the La Liga Filipina, which included Bonifacio and Deodato Arellano, founded the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK), called simply the Katipunan, which had the objective of the Philippines seceding from the Spanish Empire.

The Philippine Revolution

By 1896 the Katipunan had a membership by the thousands. That same year, the existence of the Katipunan was discovered by the colonial authorities. In late August Katipuneros gathered in Caloocan and declared the start of the revolution. The event is now known as the Cry of Balintawak or Cry of Pugad Lawin, due to conflicting historical traditions and official government positions.[28]

Andrés Bonifacio called for a general offensive on Manila[29] and was defeated in battle at the town of San Juan del Monte. He regrouped his forces and was able to briefly capture the towns of Marikina, San Mateo and Montalban. Spanish counterattacks drove him back and he retreated to the mountains of Balara and Morong and from there engaged in guerrilla warfare.[30] By August 30, the revolt had spread to eight provinces. On that date, Governor-General Ramon Blanco declared a state of war in these provinces and placed them under martial law. These were Manila, Bulacan, Cavite, Pampanga, Tarlac, Laguna, Batangas, and Nueva Ecija. They would later be represented in the eight rays of the sun in the Filipino flag.[31] Emilio Aguinaldo and the Katipuneros of Cavite were the most successful of the rebels[32] and they controlled most of their province by September–October. They defended their territories with trenches designed by Edilberto Evangelista.[30]

Many of the educated ilustrado class such as Antonio Luna and Apolinario Mabini did not initially favor an armed revolution. Rizal himself, whom the rebels took inspiration from and had consulted beforehand, disapproved of a premature revolution. He was arrested, tried and executed for treason, sedition and conspiracy on December 30, 1896. Before his arrest he had issued a statement disavowing the revolution, but in his swan song poem Mi último adiós he wrote that dying in battle for the sake of one's country was just as patriotic as his own impending death.[33]

While the revolution spread throughout the provinces, Aguinaldo's Katipuneros declared the existence of an insurgent government in October regardless of Bonifacio's Katipunan,[34] which he had already converted into an insurgent government with him as president in August.[35][36] Bonifacio was invited to Cavite to mediate between Aguinaldo's rebels, the Magdalo, and their rivals the Magdiwang, both chapters of the Katipunan. There he became embroiled in discussions whether to replace the Katipunan with an insurgent government of the Cavite rebels' design. To this end, the Tejeros Convention was convened, where Aguinaldo was elected president of the new insurgent government. Bonifacio refused to recognize this and he was executed for treason in May 1897.[37][38]

By December 1897, the revolution had resulted to a stalemate between the colonial government and rebels. Pedro Paterno mediated between the two sides for the signing of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. The conditions of the armistice included the self-exile of Aguinaldo and his officers in exchange for $800,000 to be paid by the colonial government. Aguinaldo then sailed to Hong Kong for self exile.

The Spanish–American War

On April 25, 1898, the Spanish–American War began with declarations of war. On May 1, 1898, the Spanish navy was decisively defeated in the Battle of Manila Bay by the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Navy led by Commodore George Dewey aboard the USS Olympia. Thereafter Spain lost the ability to defend Manila and therefore the Philippines.

On May 19, Emilio Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines aboard an American naval ship and on May 24 took command of Filipino forces. Filipino forces had liberated much of the country from the Spanish. On June 12, 1898 Aguinaldo issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence declaring independence from Spain and later established the First Philippine Republic. Filipino forces then laid siege to Manila, as had American forces.

The Americans entered into a pact with the Spanish governor-general in which they agreed to fight a mock battle before surrendering Manila to the Americans. The Battle of Manila took place on August 13 and Americans took control of the city. In the Treaty of Paris (1898) ending the Spanish–American War, the Spanish agreed to sell the Philippines to the United States for $20 million which was subsequently narrowly ratified by the U.S. Senate. With this action, Spanish rule in the Philippines formally ended.

On February 4, 1899, the Philippine–American War began with the Battle of Manila (1899) between Americans forces and the nascent Philippine Republic.

References

- ↑ Zaide 2006, p. 78

- ↑ Zaide 2006, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 73

- ↑ Zaide 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Zaide 1939, p. 113

- ↑ Scott 1985, p. 51.

- ↑ Williams 2009, pp. 13–33.

- 1 2 3 M.c. Halili (2004). Philippine History' 2004 Ed.-halili. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ↑ Schottenhammer 2008, p. 151.

- ↑ Yu-Jose 1999, p. http://books.google.com/books?id=kbWv-pZy5H0C&pg=PA1 1.

- ↑ Villarroel 2009, pp. 93–133.

- ↑ .Abinales & Amoroso 2005, p. 55.

- ↑ South East Asia Pottery - Philippines

- ↑ Solidarity 2 (8–10), Solidaridad Publishing House, p. 8, "The charter of the Royal Philippine Company was promulgated on March 10, 1785 tolast for 25 years."

- ↑ De Borja & Douglass 2005, pp. 71–79.

- ↑ "Rostros de piedra; biografías de un mundo perdido" (PDF). Miaka1 Cuadernos de investigación. San Telmo Museoa. Retrieved 2014-10-06. p. 68

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 82–83

- ↑ McCoy & de Jesus 2001, p. 233.

- 1 2 3 De Jesus, Luis & De Santa Theresa, Diego. "Recollect Missions, 1646–1660", in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1905). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898 (Project Gutenberg). Volume 36 of 55 (1649–1666). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE; additional translations by Henry B. Lathrop. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ASIN B004TRONB2.(pp126 ff.)

- 1 2 3 Fayol, Joseph. "Affairs in Filipinas, 1644–47", in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1905). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 35 of 55. Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE;. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company.(p267)

- 1 2 3 Maarten Gerritszoon Vries; Cornelis Janszoon Coen, Pieter Arend Leupe, Philipp Franz von Siebold, K. (1858). Reize van Maarten Gerritsz: Vries in 1643 naar het noorden en oosten van Japan. Instituut voor de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, The Hague. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Tracy 1995, p. 9

- ↑ Tracy 1995, p. 54

- ↑ Fish 2003, p. 158

- ↑ Tracy 1995, p. 109

- ↑ Cummins 2006, pp. 132–138

- ↑ Sagmit & Sagmit-Mendoza 2007, p. 127.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 166

- ↑ Salazar 1994, p. 107.

- 1 2 Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 173.

- ↑ Constantino 1975, p. 179

- ↑ Quibuyen 2008

- ↑ Constantino 1975, pp. 178–181

- ↑ Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 166–167Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 152

- ↑ Constantino 1975, p. 191

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 180–181.

Citations

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990), History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.), University of the Philippines, ISBN 971-8711-06-6.

- Abinales, P. N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005), State and Society in the Philippines, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, Quezon City: Tala Publishing Services, ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Cummins, Joseph (2006), "11. A Legend of Freedom: Francisco Dagohoy and the Rebels of Bohol", History's great untold stories: obscure events of lasting importance, Murdoch Books, pp. 132–138, ISBN 978-1-74045-808-5.

- De Borja, Marciano R.; Douglass, William A. (2005), Basques in the Philippines, University of Nevada Press, ISBN 978-0-87417-590-5.

- Fish, Shirley (2003), When Britain ruled the Philippines, 1762-1764: the story of the 18th century British invasion of the Philippines during the Seven Years' War, 1stBooks Library, ISBN 978-1-4107-1069-7, ISBN 1-4107-1069-6, ISBN 978-1-4107-1069-7.

- Guerrero, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1.

- McCoy, Alfred W.; de Jesus, Ed. C. (2001), Philippine social history: global trade and local transformations, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-279-5.

- Newson, Linda (2009), Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines, University of Hawai‘i Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3272-8.

- Quibuyen, Floro C. (2008) [1999], A Nation Aborted: Rizal, American Hegemony, and Philippine nationalism (Revised ed.), Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-574-1.

- Sagmit, Rosario S.; Sagmit-Mendoza, Ma. Lourdes (2007), The Filipino Moving Onward 5', Rex Bookstore, Inc., ISBN 978-971-23-4154-0.

- Schottenhammer, Angela (2008), The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4.

- Scott, William Henry (1985), Cracks in the parchment curtain and other essays in Philippine history, New Day Publishers, ISBN 978-971-10-0074-5.

- Spate, Oskar Hermann Khristian (2004), The Spanish Lake, Australian National University, ISBN 1-920942-16-5.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1995), Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years' War, University of Exeter Press, ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5.

- Villarroel, Fidel (2009), "Philip II and the "Philippine Referendum" of 1599", in Ramírez, Dámaso de Lario, Re-shaping the World: Philip II of Spain and His Time (illustrated ed.), Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-556-7.

- Williams, Patrick (2009), "Philip II, the Philippines, and the Hispanic World", in Ramírez, Dámaso de Lario, Re-shaping the World: Philip II of Spain and His Time (illustrated ed.), Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-556-7.

- Yu-Jose, Lydia N. (1999), Japan views the Philippines, 1900-1944, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-281-8.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1939), Philippine History and Civilization, Philippine Education Co..

- Zaide, Sonia M (2006), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co Inc, Quezon City, ISBN 971-642-071-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of the Philippines (1521–1898). |

- Shamanism, Catholicism and Gender Relations in Colonial Philippines 1521-1685 – Google Books

- De las islas filipinas A historical account written by a Spanish lawyer who lived in the Philippines during the 19th century

- Timeline of Philippine History: Spanish colonization

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||