History of the Jews and Judaism in the Land of Israel

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Israel |

|

| Ancient Israel and Judah |

| Second Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE) |

| Middle Ages (70–1517) |

| Modern history (1517–1948) |

| State of Israel (1948–present) |

| History of the Land of Israel by topic |

| Related |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Palestine |

| Prehistory |

| Iron Age |

| Persian Empire |

| Hellenistic |

| Roman period |

| Islamic rule |

| Modern era |

| Palestine portal |

The Jewish people have long maintained both physical and religious ties with the land of Israel. The first appearance of the name "Israel" in the historic record is the Merneptah Stele, circa 1200 BCE. During the biblical period, two kingdoms occupied the highland zone, the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) in the north and the Kingdom of Judah in the south. The Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (circa 722 BCE) and the Kingdom of Judah by the Neo-Babylonian Empire (586 BCE). Upon the defeat of the Babylonian Empire by the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great, the Jewish elite returned to Jerusalem and the Second Temple was built.

In 165 BCE, the independent Hasmonean Kingdom was established. Although coming under the sway of various empires and home to a variety of ethnicities, the area of ancient Israel was predominantly Jewish until the Jewish–Roman wars. After this time, Jews became a minority in most regions, except Galilee. The area became increasingly Christian after the 3rd century, though the percentages of Christians and Jews are unknown, the former perhaps coming to predominate in urban areas, the latter remaining in rural areas[1] Jewish settlements declined from over 160 to 50 by the time of the Muslim conquest. Michael Avi-Yonah calculated that Jews constituted 10-15% of Palestine's population by the time of the Persian invasion of 614.[2] while Moshe Gil claims that Jews constituted the majority of the population until 7th century Muslim conquest.[3]

Etymology

The term Jews in its original meaning refers to the people of the tribe of Judah or the people of the kingdom of Judah. The name of both the tribe and kingdom derive from Judah, the fourth son of Jacob.[4] Originally, the Hebrew term Jews Yehudi referred only to members of the tribe of Judah. Later, after the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel, the term Jews was applied for the tribes of Judah, Benjamin and Levi, as well as scattered settlements from other tribes.[5]

The land of Israel, which is considered by Jews to be the promised land, was the place where Jewish identity was formed,[6] although this identity was formed gradually reaching many of its current form in the Exilic and post-Exilic period.[7] By the Hellenistic period (after 332 BCE) the Jews had become a self-consciously separate community based in Jerusalem.

Ancient times

Early Israelites

The name Israel first appears in the stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah c. 1209 BC, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not."[8] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity of the central highlands, well enough established to be perceived by the Egyptians as a possible challenge to their hegemony, but an ethnic group rather than an organized state.[9] Ancestors of the Israelites may have included Semites who occupied Canaan and the Sea Peoples.[10] According to modern archaeologists, sometime during Iron Age I a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite', differentiating itself from the Canaanites through such markers as the prohibition of intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[11]

Villages had populations of up to 300 or 400,[12][13] which lived by farming and herding, and were largely self-sufficient;[14] economic interchange was prevalent.[15] Writing was known and available for recording, even in small sites.[16] The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population.[17]

Israel and Judah

The archaeological record indicates that the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah emerged in the Early Iron Age (Iron Age I, 1200–1000 BCE) from the Canaanite city-state culture of the Late Bronze Age, at the same time and in the same circumstances as the neighbouring states of Edom, Moab, Aram, and the Philistinian and Phoenician city-states.[18] The oldest Hebrew text ever found was discovered at the ancient Israelite settlement, Elah Fortress,[19] which dates to between 1050 and 970 BCE.[20]

The Bible states that David founded a dynasty of kings and that his son Solomon built a Temple. Possible references to the House of David have been found at two sites, the Tel Dan Stele and the Mesha Stele.[21] Yigael Yadin's excavations at Hazor, Megiddo, Beit Shean and Gezer uncovered structures that he and others have argued date from Solomon's reign,[22] but others, such as Israel Finkelstein and Neil Silberman (who agree that Solomon was a historical king), argue that they should be dated to the Omride period, more than a century after Solomon.[23]

By around 930 BCE, Judaism was divided into a southern Kingdom of Judah and a northern Kingdom of Israel. By the middle of the 9th century BCE, it is possible that an alliance between Ahab of Israel and Ben Hadad II of Damascus managed to repulse the incursions of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, with a victory at the Battle of Qarqar (854 BCE).[24] The Tel Dan stele tells of the death of a king of Israel, probably Jehoram, at the hands of an Aramean king (c. 841).[25]

From the middle of the 8th century BCE Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding neo-Assyrian empire. Under Tiglath-Pileser III it first split Israel's territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722 BCE). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of the people of Israel and their replacement with an equally large number of forced settlers from other parts of the empire – such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure - and the former Israel never again became an independent political entity.[26] This deportation gave rise to the notion of the Lost Tribes of Israel. The Samaritan people claim to be descended from survivors of the Assyrian conquest.

The recovered seal of the Ahaz, king of Judah, (c. 732–716 BCE) identifies him as King of Judah.[27] The Assyrian king Sennacherib, tried and failed to conquer Judah. Assyrian records say he leveled 46 walled cities and besieged Jerusalem, leaving after receiving tribute.[28] During the reign of Hezekiah (c. 716–687 BCE) a notable increase in the power of the Judean state is reflected by archaeological sites and findings such as the Broad Wall and the Siloam Tunnel in Jerusalem.[29]

Judah prospered in the 7th century BCE, probably in a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian vassal (despite a disastrous rebellion against the Assyrian king Sennacherib). However, in the last half of the 7th century Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between the Egyptian and Neo-Babylonian empires for control of Palestine led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.[30]

Exile under Babylon (586–538 BCE)

The Assyrian Empire was overthrown in 612 BCE by the Medes and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. In 586 BCE King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered Judah. According to the Hebrew Bible, he destroyed Solomon's Temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon. The defeat was also recorded by the Babylonians in the Babylonian Chronicles.[31][32] The exile of Jews may have been restricted to the elite.

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[33] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.[34] Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town of Mizpah in Benjamin in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud Medinata.[35] (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location).[36] There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.[37]

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple, but the ruination of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.[38] The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"[39] the idea that Yahweh, God of Israel, had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.[40] The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community – kings, priests, scribes and prophets – to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.[41] The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah 40–55, Ezekiel, the final version of Jeremiah, the work of the Priestly source in the Pentateuch, and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings[42] Theologically, they were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world), and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.[42] Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of identity as a people distinct from other peoples,[43] and increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to maintain that separation.[44]

Classical era (538 BCE–636 CE)

Persian rule (538–332 BCE)

In 538 BCE, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon and took over its empire. Judah remained a province of the Persian empire until 332 BCE. According to the biblical history, Cyrus issued a proclamation granting subjugated nations their freedom. Jewish exiles in Babylon, including 50,000 Judeans, led by Zerubabel returned to Judah to rebuild the temple, a task which they are said to have completed c. 515.[45] A second group of 5,000, led by Ezra and Nehemiah, returned to Judah in 456 BCE although non-Jews wrote to Cyrus to try to prevent their return. Yet it was probably only in the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah.[46] The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Judah as a Dividic client-kingdom under descendants of Jehoiachin,[47] but by the mid–5th century BCE Judah had become in practice a theocracy, ruled by hereditary High Priests[48] and a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that tribute was paid.[49] According to the biblical history, Ezra and Nehemiah arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century BCE, the first empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the second with the status of governor and a royal mission to restore the walls of the city.[50] The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Judah, the former rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism which the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, partly on disputes over property.[51] The careers of Ezra and Nehemiah in the 5th century BCE were thus a kind of religious colonisation in reverse, an attempt by one of the many Jewish factions in Babylon to create a self-segregated, ritually pure society inspired by the prophesies of Ezekiel and his followers.[52]

Hellenistic and Hasmonean era (332–64 BCE)

In 332 BCE the Persians were defeated by Alexander the Great. After his death in 322 BCE, his generals divided the empire between them and Judea became the frontier between the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Egypt, but in 198 Judea was incorporated into the Seleucid Kingdom.

At first, relations between the Seleucids and the Jews were cordial, but later on as the relations between the hellenized Jews and the religious Jews deteriorated, the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174–163) attempted to impose decrees banning certain Jewish religious rites and traditions. Consequently, this sparked a national rebellion led by Judas Maccabeus. The Maccabean Revolt (174–135 BCE), whose victory is celebrated in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah, is retold in the Books of the Maccabees. A Jewish group called the Hasideans opposed both Seleucid Hellenism and the revolt, but eventually gave their support to the Maccabees. The Jews prevailed with the expulsion of the Syrians and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty.

The Maccabean Revolt led to a twenty-five-year period of Jewish independence due to the steady collapse of the Seleucid Empire under attacks from the rising powers of the Roman Republic and the Parthian Empire. The Hasmonean dynasty of priest-kings ruled Judea with the Pharisees, Saducees and Essenes as the principal social movements. As part of their struggle against Hellenistic civilization, the Pharisees established what may have been the world's first national male (religious) education and literacy program, based around synagogues.[53] Justice was administered by the Sanhedrin, whose leader was known as the Nasi. The Nasi's religious authority gradually superseded that of the Temple's high priest (under the Hasmoneans this was the king). In 125 BCE the Hasmonean King John Hyrcanus subjugated Edom and forcibly converted the population to Judaism.[54]

The same power vacuum that enabled the Jewish state to be recognized by the Roman Senate c. 139 BCE after the demise of the Seleucid Empire was next exploited by the Romans themselves. Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, Simon's great-grandsons, became pawns in a proxy war between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great that ended with the kingdom under the supervision of the Roman governor of Syria (64 BCE).

Roman era (64 BCE – 324 CE)

| 1st-century BCE – 2nd-century CE |

|---|

|

64 BCE

115–117 |

In 63 BCE the Roman general Pompey sacked Jerusalem and made the Jewish kingdom a client of Rome. The situation was not to last, as the deaths of Pompey in 48 BCE and Caesar in 44 BCE, together with the related Roman civil wars, relaxed Rome's grip on Judea. This resulted in the Parthian Empire and their Jewish ally Antigonus the Hasmonean defeating the pro-Roman Jewish forces (high priest Hyrcanus II, Phasael and Herod the Great) in 40 BCE. They invaded the Roman eastern provinces and managed to expel the Romans. Antigonus was made King of Judea. Herod fled to Rome where he was elected "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate and was given the task of retaking Judea. In 37 BCE, with Roman support, Herod reclaimed Judea and the short lived reemergence of the Hasmonean dynasty came to an end. From 37 BCE to 6 CE, the Herodian dynasty, Jewish-Roman client kings, ruled Judea. In 20 BCE, Herod began a refurbishment and expansion of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. His son, Herod Antipas, founded the Jewish city of Tiberias in the Galilee.

Judea under Roman rule was at first a client kingdom, but gradually the rule over Judea became less and less Jewish, until it became under the direct rule of Roman administration from Caesarea Maritima, which was often callous and brutal in its treatment of its Judean, Galilean, and Samaritan subjects. In this period Rabbinical Judaism, led by Hillel the Elder, began to assume popular prominence over the Temple priesthood.

In 66 CE, the Jews of Judea rose in revolt against Rome, naming their new kingdom "Israel"[55] (see also First Jewish Revolt coinage). The events were described by the Jewish historian Josephus, including the desperate defence of Jotapata, the siege of Jerusalem (69–70 CE) and heroic last stand at Gamla where 9,000 died and Massada (72–73 CE) where they killed themselves rather than fall into the hand of their enemies.

The revolt was crushed by the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus. The Romans destroyed much of the Temple in Jerusalem and took as punitive tribute the Menorah and other Temple artefacts back to Rome. Josephus writes that 1,100,000 Jews perished during the revolt, while a further 97,000 were taken captive. The Fiscus Judaicus was instituted by the Empire as part of reparations.

It was during this period that the split of early Christianity and Judaism occurred. The Pharisee movement, led by Yochanan ben Zakai, made peace with Rome and survived. Judeans continued to live in their land in significant numbers, and were allowed to practice their religion. An estimated 2/3 of the population in the Galilee and 1/3 of the coastal region were Jewish.[56]

The 2nd century saw two further Jewish revolts against the Roman rule. The Kitos War (115–117) was followed by the more fierce Bar-Kochba revolt (132–136) led by Simon Bar Kokhba. Judea was ravaged while Julius Severus and Emperor Hadrian crushed the rebellion. According to Cassius Dio, 580,000 Jews were killed, and 50 fortified towns and 985 villages razed.[57][58]

In 131, Emperor Hadrian renamed Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina and constructed a Temple of Jupiter on the site of the former Jewish temple. Jews were banned from Jerusalem and Roman Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina, from which derived "Palestine" in English and "Filistin" in Arabic.[59]

After suppressing the Bar Kochba revolt, the Romans permitted a hereditary rabbinical patriarch from the House of Hillel to represent the Jews in dealings with the Romans. The most famous of these was Judah the Prince. Jewish seminaries continued to produce scholars, of whom the most astute became members of the Sanhedrin.[60] The remaining Jewish population was now centred in the Galilee. In this era, according to a popular theory, the Council of Jamnia developed the Jewish Bible canon which decided which books of the Hebrew Bible were to be included, the Jewish apocrypha being left out.[61] It was also the time when the tannaim and amoraim were active in debating and recording the Jewish Oral Law. Their discussions and religious instructions were compiled in the form the Mishnah by Judah the Prince around 200 CE. Various other compilations, including the Beraita and Tosefta, also come from this period. These texts were the foundation of the Jerusalem Talmud, which was redacted in around 400 CE, probably in Tiberias.

Continued persecution and the economic crisis that affected the Roman empire in the 3rd-century led to further Jewish migration from Palestine to the more tolerant Persian Sassanid Empire, where a prosperous Jewish community existed in the area of Babylon.

Byzantine period (324–638)

| Byzantine period |

|---|

|

351–352 |

Early in the 4th century, Roman Empire split and Constantinople became the capital of the East Roman Empire known as the Byzantine Empire. Under the Byzantines, Christianity, dominated by the (Greek) Orthodox Church, was adopted as the official religion. Jerusalem became a Christian city and Jews were still banned from living there.

In 351–2, there was another Jewish revolt against a corrupt Roman governor.[62] The Jewish population in Sepphoris rebelled under the leadership of Patricius against the rule of Constantius Gallus. The revolt was eventually subdued by Ursicinus.

According to tradition, in 359 CE Hillel II created the Hebrew calendar based on the lunar year. Until then, The entire Jewish community outside the land of Israel depended on the calendar sanctioned by the Sanhedrin; this was necessary for the proper observance of the Jewish holy days. However, danger threatened the participants in that sanction and the messengers who communicated their decisions to distant congregations. As the religious persecutions continued, Hillel determined to provide an authorized calendar for all time to come.

During his short reign, Emperor Julian (361–363) abolished the special taxes paid by the Jews to the Roman government and also sought to ease the burden of mandatory Jewish financial support of the Jewish patriarchate.[63] He also gave permission for the Jews to rebuild and populate Jerusalem.[64] In one of his most remarkable endeavours, he initiated the restoration of the Jewish Temple which had been demolished in 70 CE. A contingent of thousands of Jews from Persian districts hoping to assist in the construction effort were killed en route by Persian soldiers.[65] The great earthquake together with Julian's death put an end to Jewish hopes of rebuilding the Third Temple.[66] Had the attempt been successful, it is likely that the re-establishment of the Jewish state with its sacrifices, priests and Sanhedrin or Senate would have occurred.[63]

Jews probably constituted the majority of the population of Palestine until the 4th-century, when Constantine converted to Christianity.[67]

Jews lived in at least forty-three Jewish communities in Palestine: twelve towns on the coast, in the Negev, and east of the Jordan, and thirty-one villages in Galilee and in the Jordan valley. The persecuted Jews of Palestine revolted twice against their Christian rulers. In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire collapsed leading to Christian migration into Palestine and development of a Christian majority. Jews numbered 10–15% of the population. Judaism was the only non-Christian religion tolerated, but there were bans on Jews building new places of worship, holding public office or owning slaves. There were also two Samaritan revolts in this period.[68]

In 438, The Empress Eudocia removed the ban on Jews' praying at the Temple site and the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call "to the great and mighty people of the Jews": "Know that the end of the exile of our people has come"!

In about 450, the Jerusalem Talmud was completed.

According to Procopius, in 533 Byzantine general Belisarius took the treasures of the Jewish temple from Vandals who had taken them from Rome.

In 611, Sassanid Persia invaded the Byzantine Empire. In 613, a Jewish revolt against the Byzantine Empire joined forces with these Persian invaders to capture Jerusalem in 614. The great majority of Christians in Jerusalem were subsequently deported to Persia.[69] The Jews gained autonomy in Jerusalem, until in 617 when the Persians betrayed agreements and withdrew their forces from the region. With return of the Byzantines in 628, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius promised to restore Jewish rights and received Jewish help in ousting the Persians with the aid of Jewish leader Benjamin of Tiberias. Heraclius later reneged on the agreement after reconquering Palestine by issuing an edict banning Judaism from the Byzantine Empire and thousands of Jewish refugees fled to Egypt, following Byzantine and Ghassanid perpetrated massacres across the Galilee and Jerusalem. (Egyptian) Coptic Christians took responsibility for this broken pledge and still fast in penance.[70]

Middle Ages (636–1517)

Under Islamic rule (638–1099)

| Islamic period |

|---|

|

638 |

In 638 CE, the Byzantine Empire lost the Levant to the Arab Islamic Empire. According to Moshe Gil, at the time of the Arab conquest in 7th century, the majority of the population was Jewish or Samaritan.[3] According to one estimate, the Jews of Palestine numbered between 300,000 and 400,000 at the time.[71] After the conquest, the majority of the population (probably including many Jews) became Arabized in culture and language, many also adopting the new faith of Islam.[72] The Muslims continued to ban the building of new synagogues.[73] Until the Crusades took Palestine in 1099, various Muslim dynasties controlled Palestine. It was first ruled by the Medinah-based Rashidun Caliphs, then by the Damascus-based Umayyad Caliphate and after by the Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphs.

In succeeding centuries a common view is that Christians and Muslims were equally divided. The conversion of the Christians to Islam -Gil maintaining they were a majority- is generally thought to have occurred on a large scale only after the Crusades, in the wake of Saladin's conquest, and as a result of disaffection for the Latins.[74][75]

Historical sources mentions the settlement of Arab tribes and the establishment of new settlements in 7th century, although little archaeological records have been preserved.[76] However some Arabian settlements like Khirbet Suwwwana, located on outskirts of Jerusalem provides archaeological records of Islamic nomadic settlement and sedentarization among local population. The establishment of new Arab settlements during 7th and 8th century was relatively rare. The religious transformation of the land is evident with large congregation style mosques built in cities like Tiberias, Jarash, Beth Shean, Jerusalem and possibly Cesarea. However the establishment of these mosques point to the influx of Muslim newcomers, rather than to conversion of Jews and Christians to Islam.[77] The settlement map of the land changed dramatically between 6th and 11th century. The sixth century map revealed an urban and rural society at its height, while the 11th century map shows a society that was economically and phiscally stagnant veering toward total collapse.[78]

After the conquest, Jewish communities began to grow and flourish. Umar allowed and encouraged Jews to settle in Jerusalem. It was first time, after almost 500 years of oppressive Christian rule, that Jews were allowed to enter and worship freely in their holy city.[79] Seventy Jewish families from Tiberias moved to Jerusalem in order to help strengthen the Jewish community there.[80] But with the construction of the Dome of the Rock in 691 and the Al-Aqsa Mosque in 705, the Muslims established the Temple Mount as an Islamic holy site. The dome enshrined the Foundation Stone, the holiest site for Jews. Before Omar Abd al-Aziz died in 720, he banned the Jews from worshipping on the Temple Mount,[81] a policy which remained in place for over the next 1,000 years of Islamic rule.[82] In around 875, Karaite leader Daniel al-Kumisi arrived in Jerusalem and established an ascetic community of Mourners of Zion.[83] Michael the Syrian notes thirty synagogues which were destroyed in Tiberias by the earthquake of 749.[84]

In the mid-8th-century, taking advantage of the warring Islamic factions in Palestine, a false messiah named Abu Isa Obadiah of Isfahan inspired and organised a group of 10,000 armed Jews who hoped to restore the Holy Land to the Jewish nation. Soon after, when Al-Mansur came to power, Abu Isa joined forces with a Persian chieftain who was also conducting a rebellion against the caliph. The rebellion was subdued by the caliph and Abu Isa fell in battle in 755.[85]

In 1039, part of the synagogue in Ramla was still in ruins, probably resulting from the earthquake of 1033.[86] Jews also returned to Rafah and documents from 1015 and 1080 attest to a significant community there.[87]

A large Jewish community existed in Ramle and smaller communities inhabited Hebron and the coastal cities of Acre, Caesarea, Jaffa, Ashkelon and Gaza. Al-Muqaddasi (985) wrote that "for the most part the assayers of corn, dyers, bankers, and tanners are Jews."[88] Under the Islamic rule, the rights of Jews and Christians were curtailed and residence was permitted upon payment of the special tax.

Between the 7th and 11th centuries, Masoretes (Jewish scribes) in the Galilee and Jerusalem were active in compiling a system of pronunciation and grammatical guides of the Hebrew language. They authorised the division of the Jewish Tanakh, known as the Masoretic Text, which is regarded as authoritative till today.[89]

Under Crusader rule (1099–1291)

According to Gilbert, from 1099 to 1291 the Christian Crusaders "mercilessly persecuted and slaughtered the Jews of Palestine."[90]

In 1099, the Jews were among the rest of the population who tried in vain to defend Jerusalem against the Crusaders. When the city fell, a massacre of 6,000 Jews occurred when the synagogue they were seeking refuge in was set alight. Almost all perished.[91] In Haifa, the Jews and Muslims held out for a whole month, (June–July 1099).[92]

Under Crusader rule, Jews were not allowed to hold land and involved themselves in commerce in the coastal towns during times of quiescence. Most of them were artisans: glassblowers in Sidon, furriers and dyers in Jerusalem. At this time there were Jewish communities scattered all over the country, including Jerusalem, Tiberias, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Gaza. In line with trail of bloodshed the Crusaders left in Europe on their way to liberate the Holyland, in Palestine, both Muslims and Jews were indiscriminately massacred or sold into slavery.[93]

A large volume of piyutim and midrashim originated in Palestine at this time. In 1165 Maimonides visited Jerusalem and prayed on the Temple Mount, in the "great, holy house".[94] In 1141 Spanish poet, Yehuda Halevi, issued a call to the Jews to emigrate to the Land of Israel, a journey he undertook himself.

In the crusading era, there were significant Jewish communities in several cities and Jews are known to have fought alongside Arabs against the Christian invaders.[95]

Gradual revival with increased immigration (1211–1517)

| ||

|

The Crusader rule over Palestine had taken its toll on the Jews. Relief came in 1187 when Ayyubid Sultan Saladin defeated the Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin, taking Jerusalem and most of Palestine. (A Crusader state centred round Acre survived in weakened form for another century.) In time, Saladin issued a proclamation inviting all Jews to return and settle in Jerusalem,[96] and according to Judah al-Harizi, they did: "From the day the Arabs took Jerusalem, the Israelites inhabited it."[97] al-Harizi compared Saladins decree allowing Jews to re-establish themselves in Jerusalem to the one issued by the Persian Cyrus the Great over 1,600 years earlier.[98]

In 1211, the Jewish community in the country was strengthened by the arrival of a group headed by over 300 rabbis from France and England,[99] among them Rabbi Samson ben Abraham of Sens.[100] The motivation of European Jews to emigrate to the Holyland in the 13th-century possibly lay in persecution,[101] economic hardship, messianic expectations or the desire to fulfill the commandments specific to the land of Israel.[102] In 1217, Spanish pilgrim Judah al-Harizi found the sight of the non-Jewish structures on the Temple Mount profoundly disturbing: "What torment to see our holy courts converted into an alien temple!" he wrote.[103] Nachmanides, the 13th-century Spanish rabbi and recognised leader of Jewry greatly praised the land of Israel and viewed its settlement as a positive commandment incumbent on all Jews. He wrote "If the gentiles wish to make peace, we shall make peace and leave them on clear terms; but as for the land, we shall not leave it in their hands, nor in the hands of any nation, not in any generation."[104] In 1267 he arrived in Jerusalem and found only two Jewish inhabitants — brothers, dyers by trade. Wishing to re-establish a strong Jewish presence in the holy city, he brought a Torah scroll from Nablus and founded a synagogue. Nahmanides later settled at Acre, where he headed a yeshiva together with Yechiel of Paris who had emigrated to Acre in 1260, along with his son and a large group of followers.[105][106] Upon arrival, he had established the Beth Midrash ha-Gadol d'Paris Talmudic academy where one of the greatest Karaite authorities, Aaron ben Joseph the Elder, was said to have attended.[107]

In 1260, control passed to the Egyptian Mamluks and until 1291 Palestine became the frontier between Mongol invaders (occasional Crusader allies). The conflict impoverished the country and severely reduced the population. Sultan Qutuz of Egypt eventually defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut (near Ein Harod) and his successor (and assassin), Baibars, eliminated the last Crusader Kingdom of Acre in 1291, thereby ending the Crusader presence.

In 1266 the Mamluk Sultan Baybars converted the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron into an exclusive Islamic sanctuary and banned Christians and Jews from entering, which previously would be able to enter it for a fee. The ban remained in place until Israel took control of the building in 1967.[108][109] In 1286, leader of German Jewry Meir of Rothenburg, was imprisoned by Rudolf I for attempting to lead a large group of Jews hoping to settle in Palestine.[110] Exiled from France in 1306, Ishtori Haparchi (d. 1355) arrived in Palestine and settled Bet She'an in 1313. Over the next seven years he compiled an informative geographical account of the land in which he attempts to identify biblical and talmudic era locations.[111] Two other noted Spanish kabbalists, Hananel ibn Askara and Shem Tov ibn Gaon, emigrated to Safed around this time.[112] During the tolerant reign of Nassir Mahomet (1299–1341) Jewish pilgrims from Egypt and Syria were able to spend the festivals in Jerusalem, which had a large Jewish community.[112] Many of the Jerusalem Jews occupied themselves with study of the codes and the kabbalah. Others were artisans, merchants, calligraphers or physicians.[112] The vibrant community of Hebron engaged in weaving, dyeing and glassware manufacturing; others where shepherds.[112]

The 1428 attempt by German Jews to acquire rooms and buildings on Mount Zion over the Tomb of David had dire consequences. The Franciscans, who had occupied the site since 1335, petitioned Pope Martin V who issued a papal order prohibiting sea captains from carrying Jews to Palestine.[113] In 1438, Italian rabbi Elijah of Ferrara settled in Jerusalem and became a lecturer and dayyan.[114] In 1455, a large group of prospective emigrants from across Sicily were arrested for attempting to sail to Palestine.[115] Not wanting to forfeit revenue made from special Jewish taxes, the authorities were against the mass emigration of Jews and accused the group of planning to illegally smuggle gold off the island. After nine months of imprisonment, a heavy ransom freed 24 Jews who were then granted permission to travel to Palestine so long as they abandoned all their property.[116]

In 1470, Isaac b. Meir Latif arrived from Ancona and counted 150 Jewish families in Jerusalem.[114] In 1473, the authorities closed down the Nachmanides Synagogue after part of it had collapsed in a heavy rainstorm. A year later, after an appealing to Sultan Qaitbay, the Jews were given permission to repair it. The Muslims of the adjoining mosque however contested the verdict and for two days, proceeded to demolish the synagogue completely. The vandals were punished, but the synagogue was only rebuilt 50 years later in 1523.[117] 1481 saw Italian Joseph Mantabia being appointed dayyan in Jerusalem.[118] A few years later in 1488, Italian commentator and spiritual leader of Jewry, Obadiah ben Abraham arrived in Jerusalem. He found the city forsaken holding about seventy poor Jewish families.[119] By 1495, there were 200 families. Obadiah, a dynamic and erudite leader, had begun the rejuvenation of Jerusalem's Jewish community. This, despite the fact many refugess from the Spanish and Portuguese expulsion of 1492-97 stayed away worried about the lawlessness of Mamulk rule.[120] An anonymous letter of the time lamented: "In all these lands there is no judgement and no judge, especially for the Jews against Arabs."[120] Mass immigration would start after the Turks conquered the region in 1517.[120] Yet in Safed, the situation fared better. Thanks to Joseph Saragossi who had arrived in the closing years of the 15th century, Safed and its environs had developed into the largest concentration of Jews in Palestine. With the help of the Sephardic immigration from Spain, the Jewish population had increased to 10,000 by the early 16th century.[121] Twenty-five years earlier Joseph Mantabia had counted just 300 families in and around Safed.[122] The first record of Jews at Safed was provided by French explorer Samuel ben Samson 300 years earlier in 1210 when he found only 50 Jews in residence.[122] At the beginning of the 17th century, Safed was to boast eighteen talmudical colleges and twenty-one synagogues.[123]

Records cite at least 30 Jewish urban and rural communities in the country at the opening of the 16th century.

Modern history (1517–present)

Growth and stability under Ottoman rule (1517–1917)

Palestine was conquered by Turkish Sultan Selim II in 1516–17, and became part of the province of Syria for the next four centuries.

In 1534, Spanish refugee Jacob Berab settled in Safed. He believed the time was ripe to reintroduce the old "semikah" (ordination) which would create for Jews worldwide a recognised central authority.[125] In 1538, an assembly of Safed twenty-five rabbis ordained Berab, a step which they hoped would instigate the formation of a new Sanhedrin. But the plan faltered upon a strong and concerted protest by the chief rabbi of Jerusalem, Levi ben Jacob ibn Habib.[125] Additionally, worried about a scheme which would invest excessive authority in a Jewish senate, possibly resulting in the first step toward the restoration of the Jewish state, the new Ottoman rulers forced Berab to flee Palestine and the plan did not materialize.[125] The 16th-century nevertheless saw a resurgence of Jewish life in Palestine. Palestinian rabbis were instrumental producing a universally accepted manual of Jewish law and some of the most beautiful liturgical poems. Much of this activity occurred at Safed which had become a spiritual centre, a haven for mystics. Joseph Karo's comprehensive guide to Jewish law, the Shulchan Aruch, was considered so authoritative that the variant customs of German-Polish Jewry were merely added as supplement glosses.[126] Some of the most celebrated hymns were written at in Safed by poets such as Israel Najara and Solomon Alkabetz.[127] The town was also a centre of Jewish mysticism, notable kabbalists included Moses Cordovero and the German-born Naphtali Hertz ben Jacob Elhanan.[128][129][130] A new method of understanding the kabbalah was developed by Palestinian mystic Isaac Luria, and espoused by his student Chaim Vital. In Safed, the Jews developed a number of branches of trade, especially in grain, spices, textiles and dyeing. In 1577, a Hebrew printing press was established in Safed. The 8,000 or 10,000 Jews in Safed in 1555 grew to 20,000 or 30,000 by the end of the century.

| Old Yishuv |

|---|

|

| Key events |

|

| Key figures |

|

| Economy |

| Philanthropy |

| Communities |

| Synagogues |

| Related articles |

In around 1563, Joseph Nasi secured permission from Sultan Selim II to acquire Tiberias and seven surrounding villages to create a Jewish city-state.[131] He hoped that large numbers of Jewish refugees and Marranos would settle there, free from fear and oppression; indeed, the persecuted Jews of Cori, Italy, numbering about 200 souls, decided to emigrate to Tiberias.[132][133] Nasi had the walls of the town rebuilt by 1564 and attempted to turn it into a self-sufficient textile manufacturing center by planting mulberry trees for the cultivation of silk. Nevertheless, a number of factors during the following years contributed to the plan's ultimate failure. Nasi's aunt, Doña Gracia Mendes Nasi supported a yeshiva in the town for many years until her death in 1569.[134]

In 1567, a Yemenite scholar and Rabbi, Zechariah Dhahiri, visited Safed and wrote of his experiences in a book entitled Sefer Ha-Musar. His vivid descriptions of the town Safed and of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s yeshiva are of primary importance to historians, seeing that they are a first-hand account of these places, and the only extant account which describes the yeshiva of the great Sephardic Rabbi, Joseph Karo.[135]

In 1576, the Jewish community of Safed faced an expulsion order: 1,000 prosperous families were to be deported to Cyprus, "for the good of the said island", with another 500 the following year.[136] The order was later rescinded due to the realisation of the financial gains of Jewish rental income.[137] In 1586, the Jews of Istanbul agreed to build a fortified khan to provide a refuge for Safed's Jews against "night bandits and armed thieves."[136]

In 1569, the Radbaz moved to Jerusalem, but soon moved to Safed to escape the high taxes imposed on Jews by the authorities.

In 1610, the Yochanan ben Zakai Synagogue in Jerusalem was completed.[138] It became the main synagogue of the Sephardic Jews, the place where their chief rabbi was invested. The adjacent study hall which had been added by 1625 later became the Synagogue of Elijah the Prophet.[138]

In the 1648–1654 Khmelnytsky Uprising in Ukraine over 100,000 Jews were massacred, leading to some migration to Israel. In 1660 (or 1662), the majorly Jewish towns of Safed and Tiberias are destroyed by the Druze, following a power struggle in Galilee.[139][140][141][142][143][144][145] In 1665, the events surrounding the arrival of the self-proclaimed Messiah Sabbatai Zevi to Jerusalem, causes a massacre of the Jews in Jerusalem.

The Near East earthquake of 1759 destroys much of Safed killing 2000 people with 190 Jews among the dead, and also destroys Tiberias.

The disciples of the Vilna Gaon settled in the land of Israel almost a decade after the arrival of two of his pupils, R. Hayim of Vilna and R. Israel ben Samuel of Shklov. In all there were three groups of the Gaon's students which emigrated to the land of Israel. They formed the basis of the Ashkenazi communities of Jerusalem and Safed, setting up what was known as the Kollel Perushim. Their arrival encouraged an Ashkenazi revival in Jerusalem, whose Jewish community until this time was mostly Sephardi. Many of the descendants of the disciples became leading figures in modern Israeli society. The Gaon himself also set forth with his pupils to the Land, but for an unknown reason he turned back and returned to Vilna where he died soon after.

During the siege of Acre in 1799, Napoleon issued a proclamation to the Jews of Asia and Africa to help him conquer Jerusalem. The siege was lost to the British, however, and the plan was never carried out. In 1821 the brothers of murdered Jewish adviser and finance minister to the rulers of the Galilee, Haim Farkhi formed an army with Ottoman permission, marched south and conquered the Galilee. They were held up at Akko which they besieged for 14 months after which they gave up and retreated to Damascus.

During the Peasants' Revolt under Muhammad Ali of Egypt's occupation, Jews were targeted in the 1834 looting of Safed and the 1834 Hebron massacre. By 1844, some sources report that Jews had become the largest population group in Jerusalem and by 1890 an absolute majority in the city, but as a whole the Jewish population made up far less than 10% of the region.[146][147]

British Mandate (1917–1948)

Between 1882 and 1948, a series of Jewish migrations to what is the modern nation of Israel, known as Aliyahs commenced. These migrations preceded the Zionist period.

In 1917, towards the end of World War I, South Western Syria, following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, was occupied by British forces. The United Kingdom was granted control of the area west of the River Jordan now comprising the State of Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (Mandatory Palestine), and on the east bank of what later became Jordan (as a separate mandate) by the Versailles Peace Conference which established the League of Nations in 1919. Herbert Samuel, a former Postmaster General in the British cabinet, who was instrumental in drafting the Balfour Declaration was appointed the first High Commissioner of Mandatory Palestine, generally simply known as Palestine. During World War I the British had made two promises regarding territory in the Middle East. Britain had promised the local Arabs, through Lawrence of Arabia, independence for a united Arab country covering most of the Arab Middle East, in exchange for their supporting the British; and Britain had promised to create and foster a Jewish national home as laid out in the Balfour Declaration, 1917.

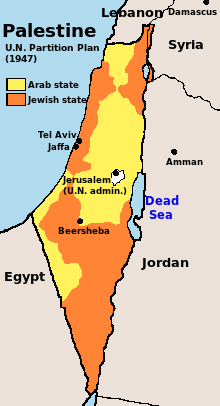

In 1947, following increasing levels of violence, the British government expressed a wish to withdraw from Palestine. The proposed plan of partition would have split Palestine into two states, an Arab state and a Jewish state, and the City of Jerusalem, giving slightly more than half the land area to the proposed Jewish state. Immediately following the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of a resolution recommending the adoption and implementation of the Partition Plan (Resolution 181(II) ), and the subsequent declaration of statehood by the Jewish National Council, civil war broke out between the Arab community and the Jewish community, as armies of the Arab League, which rejected the Partition Plan which Israel accepted, sought to squelch the new Jewish state.[148]

On 14 May 1948, one day before the end of the British Mandate, the leaders of the Jewish community in Palestine led by the future prime minister David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.[149]

State of Israel (1948–present)

The armies of Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq marched into the territory of what had just ceased to be the British Mandate, thus starting the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The nascent Israel Defense Forces repulsed the Arab armies, and extended Israel's borders beyond the original Resolution 181(II) boundaries for the proposed Jewish state.[150] By December 1948, Israel controlled most of the portion of Mandate Palestine west of the Jordan River. The remainder of the Mandate came to be called the West Bank (controlled by Jordan), and the Gaza Strip (controlled by Egypt). Prior to and during this conflict, 711,000 Palestinians Arabs[151] were expelled or fled their homes to become Palestinian refugees.[152] One third went to the West Bank and one third to the Gaza Strip, occupied by Jordan and Egypt respectively, and the rest to Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and other countries.[153]

After the establishment of Israel, immigration of Holocaust survivors from Europe and a large influx of Jewish refugees from Arab countries had doubled Israel's population within one year of its independence. Overall, during the following years approximately 850,000 Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews fled or were expelled from Arab countries, Iran and Afghanistan. Of these, about 680,000 settled in Israel.

Israel's Jewish population continued to grow at a very high rate for years, fed by waves of Jewish immigration from round the world, including the massive immigration wave of Soviet Jews, who arrived in Israel in the early 1990s, according to the Law of Return. Some 380,000 Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union arrived in 1990–91 alone.

Since 1948, Israel has been involved in a series of major military conflicts, including the 1956 Suez Crisis, 1967 Six-Day War, 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, and 2006 Lebanon War, as well as a nearly constant series of other conflicts, among them the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Despite the constant security threats, Israel—a majorly Jewish state—has thrived economically. Throughout the 1980s and the 1990s there were numerous liberalization measures: in monetary policy, in domestic capital markets, and in various instruments of governmental interference in economic activity. The role of government in the economy was considerably decreased. On the other hand, some governmental economic functions were increased: a national health insurance system was introduced, though private health providers continued to provide health services within the national system. Social welfare payments, such as unemployment benefits, child allowances, old age pensions and minimum income support, were expanded continuously, until they formed a major budgetary expenditure. These transfer payments compensated, to a large extent, for the continuous growth of income inequality, which had moved Israel from among the developed countries with the least income inequality to those with the most.

See also

- List of Jewish leaders in the Land of Israel

- Time periods in the Palestine region

- Muslim history in Palestine (Islamization)

- Israeli Jews (Palestinian Jews)

- List of Jewish communities by country

- List of Yeshivas and Midrashas in Israel

External links

- Yearning for Zion

- The conquests of Jerusalem in 614CE and 638CE within the context of attempts at Jewish restoration

- Timeline of the History of the Jews and the Land of Israel Based on "A Historical Survey of the Jewish Population in Palestine Presented to the United Nations in 1947

References

- ↑ Catherine Hezser , Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine, Mohr Siebeck, 2001 pp.170-171.

- ↑ Michael Avi-Yonah, The Jews Under Roman and Byzantine Rule: A Political History of Palestine from the Bar Kokhba War to the Arab Conquest, Magnes Press, Hebrew University, 1984, pp.15-19,20,132-3, 241 cited William David Davies,Louis Finkelstein,Steven T. Katz (eds.), The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, pp.407ffff.

- 1 2 Moshe Gil, "A History of Palestine: 634-1099", p. 3.

- ↑ "Jew", Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ "Who Is a Jew?". Judaism101. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "A history of the Jewish nation : from the earliest times to the present day (1883) (archived)". Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Ancient Jewish Religion and Culture". MyJewishLearning. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.

- ↑ Dever 2003, p. 206.

- ↑ Miller 1986, pp. 78–9.

- ↑ McNutt 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ McNutt 1999, p. 70.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ McNutt 1999, p. 72.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 99.

- ↑ Miller 2005, p. 105.

- ↑ Lehman in Vaughn 1992, pp. 156–62.

- ↑ Elizabeth Bloch-Smith and Beth Alpert Nakhai, "A Landscape Comes to Life: The Iron Age I", Near Eastern Archeology, Vol. 62, No. 2 (June 1999), pp. 62–92

- ↑ Gil Ronen (31 October 2008). "Oldest Hebrew Text Discovered at King David's Border Fortress". Israel National News.

- ↑ Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, Khirbet Qeiyafa: Sha’arayim, The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, Volume 8, Article 22. ISSN 1203-1542.

- ↑ Jerusalem: The Biography by Simon Sebag Montefiore pp 28 and 39 Phoenix 2011

- ↑ Dever 2001

- ↑ Finkelstein The Bible Unearthed

- ↑ Kurkh stela: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=367117&partId=1 For original inscription see http://rbedrosian.com/Downloads3/ancient_records_assyria1.pdf page 223

- ↑ Mazar in Finkelstein 2007, p. 163.

- ↑ Lemche 1998, p. 85.

- ↑ First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz's Seal by Robert Deutsch.

- ↑ http://www.utexas.edu/courses/classicalarch/readings/sennprism.html column 2 line 61 to column 3 line 49

- ↑ David M. Carr (2005). Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 164.

- ↑ Thompson, p410.

- ↑ http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cuneiform_nebuchadnezzar_ii.aspx

- ↑ See http://www.livius.org/cg-cm/chronicles/abc5/jerusalem.html reverse side, line 12.

- ↑ Grabbe 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Lemaire in Blenkinsopp 2003, p. 291.

- ↑ Davies 2009.

- ↑ Lipschits 2005, p. 48.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp in Blenkinsopp 2003, pp. 103–5.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 228.

- ↑ Middlemas 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Miller 1986, p. 203.

- ↑ Middlemas 2005, p. 2.

- 1 2 Middlemas 2005, p. 10.

- ↑ Middlemas 2005, p. 17.

- ↑ Bedford 2001, p. 48.

- ↑ Nodet 1999, p. 25.

- ↑ Davies in Amit 2006, p. 141.

- ↑ Niehr in Becking 1999, p. 231.

- ↑ Wylen 1996, p. 25.

- ↑ Grabbe 2004, pp. 154–5.

- ↑ Soggin 1998, p. 311.

- ↑ Miller 1986, p. 458.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 229.

- ↑ Paul Johnson, History of the Jews, p. 106, Harper 1988

- ↑

"HYRCANUS, JOHN (JOHANAN) I.". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

"HYRCANUS, JOHN (JOHANAN) I.". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

- ↑ Martin Goodman, Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations, Penguin 2008 pp. 18–19

- ↑ M. Avi-Yonah, The Jews under Roman and Byzantine Rule, Jerusalem 1984 chapter I

- ↑ The 'Five Good Emperors' (roman-empire.net)

- ↑ Mosaic or mosaic?—The Genesis of the Israeli Language by Zuckermann, Gilad

- ↑ Martin Goodman, Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations, Penguin 2008 p. 494

- ↑ M. Avi-Yonah, The Jews under Roman and Byzantine Rule, Jerusalem 1984 sections II to V

- ↑ For more information, see "The Canon Debate" edited by McDonald and Sanders, 2002 Hendrickson.

- ↑ Bernard Lazare. "Jewish History Sourcebook: Bernard Lazare: Antisemitism: Its History and Causes, 1894". Fordham University. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE" (Fordham University, The Jesuit University of New York).

- ↑ Andrew Cain; Noel Emmanuel Lenski (2009). The power of religion in late antiquity. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-0-7546-6725-4. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Abraham Malamat; Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson (1976). A History of the Jewish people. Harvard University Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Günter Stemberger (2000). Jews and Christians in the Holy Land: Palestine in the fourth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-567-08699-0. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Edward Kessler (31 March 2010). An Introduction to Jewish-Christian Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-70562-2. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ M. Avi-Yonah, The Jews under Roman and Byzantine Rule, Jerusalem 1984 chapters XI–XII

- ↑ Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World, Routledge 2003 p.191.

- ↑ While the Syrians and the Melchite Greeks ceased to observe the penance after the death of Heraclius; Elijah of Nisibis (Beweis der Wahrheit des Glaubens, translation by Horst, p. 108, Colmar 1886) see http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?letter=B&artid=1642#4756.

- ↑ Israel Cohen (1950). Contemporary Jewry: a survey of social, cultural, economic, and political conditions. Methuen. p. 310. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Lauren S. Bahr; Bernard Johnston (M.A.); Louise A. Bloomfield (1996). Collier's encyclopedia: with bibliography and index. Collier's. p. 328. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Norman Roth (8 April 2014). "Synagogues". Medieval Jewish Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 978-1-136-77155-2.

The Muslims had reinforced the Byzantine prohibition against new synagogues in Palestine after their conquest of the land...

- ↑ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, OUP Oxford, 2014 pp.332-336-

- ↑ Ira M. Lapidus,Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History , Cambridge University Press, 2012 p.201,

- ↑ The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach By Gideon Avni P:354 in reference to Moshe Gil 1992, P 112-114

- ↑ The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach By Gideon Avni P.337

- ↑ The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach By Gideon Avni P:353

- ↑ Gil p.70-71.

- ↑ Moshe Dothan; Ḥevrah la-ḥaḳirat Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-ʻatiḳoteha; Israel. Agaf ha-ʻatiḳot ṿeha-muzeʼonim (2000). Hammath Tiberias: Late synagogues. Israel Exploration Society. p. 5. ISBN 978-965-221-043-2. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Simon Sebag Montefiore (27 January 2011). Jerusalem: The Biography. Orion. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-297-85864-5. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Marina Rustow (2008). Heresy and the politics of community: the Jews of the Fatimid caliphate. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8014-4582-8. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Moshe Gil (1997). A history of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ A History of the Jewish People, A. Marx. page 259.

- ↑ Stefan C. Reif; Shulamit Reif (2002). The Cambridge Genizah collections: their contents and significance. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-81361-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Raphael Patai (15 November 1999). The Children of Noah: Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-691-00968-1. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Salo Wittmayer Baron (1952). A Social and Religious History of the Jews: High Middle Ages, 500-1200. Columbia University Press. p. 168. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana. Americana Corp. 1977. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-7172-0108-2. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ Martin Gilbert (2005). "The Jews of Palestine 636 AD to 1880". The Routledge atlas of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Psychology Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-35901-6. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ Allan D. Cooper (2009). The geography of genocide. University Press of America. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7618-4097-8. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ Alex Carmel, Peter Schäfer, Yossi Ben-Artzi. The Jewish settlement in Palestine, 634-1881. L. Reichert. p. 20.

- ↑ Jerusalem in the Crusader Period Jerusalem: Life throughout the ages in a holy city] David Eisenstadt, March 1997

- ↑ Sefer HaCharedim Mitzvat Tshuva Chapter 3. Maimonides established a yearly holiday for himself and his sons, 6 Cheshvan, commemorating the day he went up to pray on the Temple Mount, and another, 9 Cheshvan, commemorating the day he merited to pray at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

- ↑ Alan John Day; Judith Bell (1987). Border and territorial disputes. Longman. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-582-00987-5. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Abraham P. Bloch (1987). "Sultan Saladin Opens Jerusalem to Jews". One a day: an anthology of Jewish historical anniversaries for every day of the year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-88125-108-1. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Benzion Dinur (1974). "From Bar Kochba's Revolt to the Turkish Conquest". In David Ben-Gurion. The Jews in their Land. Aldus Books. p. 217. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Geoffrey Hindley (28 February 2007). Saladin: hero of Islam. Pen & Sword Military. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-84415-499-9. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Alex Carmel; Peter Schäfer; Yossi Ben-Artzi (1990). The Jewish settlement in Palestine, 634-1881. L. Reichert. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-88226-479-1. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Samson ben Abraham of Sens, Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Abraham P. Bloch (1987). One a day: an anthology of Jewish historical anniversaries for every day of the year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-88125-108-1. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Alexandra Cuffel. Call and Response: European Jewish Emigration to Egypt and Palestine in the Middle Ages, 1999.

- ↑ Karen Armstrong (29 April 1997). Jerusalem: one city, three faiths. Ballantine Books. p. 229. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ Moshe Lichtman (September 2006). Eretz Yisrael in the Parshah: The Centrality of the Land of Israel in the Torah. Devora Publishing. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-932687-70-5. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Acre (Acco) at the Wayback Machine (archived 13 October 2008)

- ↑ Shlomo Pereira (26 May 2003). "Biographical Notes: Rabbanim of the Period of the Rishonim and Achronim" (PDF).

- ↑ Benjamin J. Segal. "Returning, the Land of Israel as a Focus in Jewish History. Section III: The Biblical Age. Chapter 17: Awaiting the Messiah.".

- ↑ M. Sharon (2010). "Al Khalil". Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ↑ International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa by Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda, pp. 336–339

- ↑ The Blackwell Dictionary of Judaica, Meir of Rothenburg.

- ↑ Joan Comay; Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok (2002). Who's who in Jewish history: after the period of the Old Testament. Psychology Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-415-26030-5. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Heinrich Graetz; Bella Lowy (31 December 2009). History of the Jews, Vol. IV (in Six Volumes): From the Rise of the Kabbala (1270 CE.) to the Permanent Settlement of the Marranos in Holland (1618 CE.). Cosimo, Inc. pp. 72–75. ISBN 978-1-60520-946-3. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Abraham David; Dena Ordan (24 May 2010). To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-Israel. University of Alabama Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8173-5643-9. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- 1 2 Dan Bahat (1976). Twenty centuries of Jewish life in the Holy Land: the forgotten generations. Israel Economist. p. 48. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Berl Locker (1947). Covenant everlasting: Palestine in Jewish history. Sharon Books. p. 83. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Abraham P. Bloch (1987). "Illegal Aliyah from Sicily". One a day: an anthology of Jewish historical anniversaries for every day of the year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-88125-108-1. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Denys Pringle (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The city of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-521-39038-5. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Land of Israel: Aliyah and Absorption - Encyclopaedia Judaica | Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ Abraham P. Bloch (1987). One a day: an anthology of Jewish historical anniversaries for every day of the year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-88125-108-1. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Israel Zinberg (1978). "Spanish Exiles in Turkey and Palestine". A History of Jewish Literature: The Jewish center of culture in the Ottoman empire. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-87068-241-4. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Fannie Fern Andrews (February 1976). The Holy Land under mandate. Hyperion Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-88355-304-6. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- 1 2 Solomon Schechter (May 2003). Studies in Judaism. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-59333-039-2. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ Max Leopold Margolis; Alexander Marx (1985). A history of the Jewish people. Atheneum. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-689-70134-4. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ↑ Koren, Zalman. "The Temple and the Western Wall". Western Wall Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- 1 2 3 Jacob Berab, Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ↑ S. M. Dubnow; Simon Dubnow; Israel Friedlaender (June 2000). History of the Jews in Russia and Poland. Avotaynu Inc. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-886223-11-0. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ William Lee Holladay (June 1993). The Psalms through three thousand years: prayerbook of a cloud of witnesses. Fortress Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8006-2752-2. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

This is followed by Lekhah Dodi…a hymn composed by Rabbi Shlomo Halevy Alkabetz, a Palestinian poet of the sixteenth century.

- ↑ Raphael Patai (1 September 1990). The Hebrew goddess. Wayne State University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-8143-2271-0. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Paul A. Harrison (24 June 2004). Elements of Pantheism. Media Creations. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-59526-317-9. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Arthur A. Cohen; Paul Mendes-Flohr (February 2009). 20th Century Jewish Religious Thought: Original Essays on Critical Concepts, Movements, and Beliefs. Jewish Publication Society. p. 1081. ISBN 978-0-8276-0892-4. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Shmuel Abramski (1963). Ancient towns in Israel. Youth and Hechalutz Dept. of the World Zionist Organization. p. 238. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Franz Kobler (1952). Letters of Jews through the ages from Biblical times to the middle of the eighteenth century. Ararat Pub. Society. pp. 360–363. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Elli Kohen (2007). History of the Turkish Jews and Sephardim: memories of a past golden age. University Press of America. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7618-3600-1. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Abraham David; Dena Ordan (24 May 2010). To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-Israel. University of Alabama Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8173-5643-9. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Adena Tanenbaum, Didacticism or Literary Legerdemain? Philosophical and Ethical Themes in Zechariah Aldahiri's Sefer Hamusar, in Adaptations and Innovations: Studies on the Interaction between Jewish and Islamic Thought and Literature from the Early Middle Ages to the Late Twentieth Century, Dedicated to Professor Joel L. Kraemer, ed. Y. Tzvi Langermann and Josef Stern (Leuven: Peeters Publishers, 2008), pp. 355-79

- 1 2 Elli Kohen (2007). History of the Turkish Jews and Sephardim: memories of a past golden age. University Press of America. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-7618-3600-1. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis (18 January 1996). Cultures in conflict: Christians, Muslims, and Jews in the age of discovery. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-19-510283-3. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- 1 2 Babel Translations (Firm) (July 1987). Israel, a Phaidon art and architecture guide. Prentice Hall Press. p. 205. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Isidore Singer; Cyrus Adler (1912). The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Funk and Wagnalls. p. 283.

In 1660, under Mohammed IV. (1649-87), Safed was destroyed by the Arabs.

- ↑ Jacob De Haas (1934). History of Palestine. p. 345.

Safed, hotbed of mystics, is not mentioned in the Zebi adventure. Its community had been massacred in 1660, when the town was destroyed by Arabs, and only one Jew escaped.

- ↑ Sidney Mendelssohn. The Jews of Asia: especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. (1920) p.241. "Long before the culmination of Sabbathai's mad career, Safed had been destroyed by the Arabs and the Jews had suffered severely, while in the same year (1660) there was a great fire in Constantinople in which they endured heavy losses..."

- ↑ Franco, Moïse (1897). Essai sur l'histoire des Israélites de l'Empire ottoman: depuis les origines jusqu'à nos jours. Librairie A. Durlacher. p. 88. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

Moins de douze ans après, en 1660, sous Mohammed IV, la ville de Safed, si importante autrefois dans les annales juives parce qu'elle était habitée exclusivement par les Israélites, fut détruite par les Arabes, au point qu'il n' y resta, dit une chroniquer une seule ame juive.

- ↑ A Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine. P.409. "Sultan Seliman surrounded it with a wall in 5300 (1540), and it commenced to revive a little, and to be inhabited by the most distinguished Jewish literati; but it was destroyed again in 5420 (1660)."

- ↑ Joel Rappel. History of Eretz Israel from Prehistory up to 1882 (1980), Vol.2, p.531. "In 1662 Sabbathai Sevi arrived to Jerusalem. It was the time when the Jewish settlements of Galilee were destroyed by the Druze: Tiberias was completely desolate and only a few of former Safed residents had returned..."

- ↑ Barnai, Jacob. The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: under the patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine (University of Alabama Press 1992) ISBN 978-0-8173-0572-7; p. 14

- ↑ "How to Respond to Common Misstatements About Israel". Anti-Defamation League. 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- ↑ "The Population of Palestine Prior to 1948". MidEastWeb.org. 2005. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- ↑ Editors, Charles River (September 21, 2013). Decoding the Conflict Between Israel and the Palestinians. Charles River Editors. p. chapter 5. ISBN 978-1492783619. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel: 14 May 1948

- ↑ Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab Israeli Conflict: A History With Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's: Boston. (2004). Pg. 198

- ↑ GENERAL PROGRESS REPORT AND SUPPLEMENTARY REPORT OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION COMMISSION FOR PALESTINE, Covering the period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950, Georgia A/1367/Rev.1 23 October 1950

- ↑ Benny Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge. passim.

- ↑ Palestinian Refugees: An Overview, PRRN

Bibliography

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion: Volume II: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the 6th century BCE. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob, eds. (2003b). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. Becking, Bob. "Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10)". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Amit, Yaira, et al., eds. (2006). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns. Davies, Philip R. "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck.

- Becking, Bob, ed. (2001). Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. Sheffield Academic Press. Dijkstra, Meindert. "El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism". Missing or empty

|title=(help) Dijkstra, Meindert. "I Have Blessed You by Yahweh of Samaria and His Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel". Missing or empty|title=(help) - Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette, eds. (1999). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. Niehr, Herbert. Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill.

- Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39731-2.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded, eds. (2003). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period". Missing or empty

|title=(help) Lemaire, Andre. "Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period". Missing or empty|title=(help) - Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans.

- Brett, Mark G. (2002). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. Edelman, Diana. "Ethnicity and Early Israel". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. Stager, Lawrence E. "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Coote, Robert B.; Whitelam, Keith W. (1986). "The Emergence of Israel: Social Transformation and State Formation Following the Decline in Late Bronze Age Trade". Semeia (37): 107–47.

- Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield.

- Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9 (47).

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans.

- Doumani, Beshara (1995) Rediscovering Palestine: merchants and peasants in Jabal Nablus 1700-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press ISBN 0-520-20370-4

- Edelman, Diana, ed. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Kok Pharos.

- Farsoun, Samih K. & Naseer Aruri (2006) Palestine and the Palestinians; Westview Press ISBN 0-8133-4336-4

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. Mazar, Amihay. "The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO.

- Gordon, Benjamin Lee. New Judea: Jewish Life in Modern Palestine and Egypt, Manchester, New Hampshire, Ayer Publishing, 1977

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International.

- Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 BCE.). T&T Clark International.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2002) Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History. Leiden: Brill ISBN 90-04-12101-3

- Katz, Shmuel (1973) Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine Shapolsky Pub; ISBN 978-0-933503-03-8

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 BCE. Society of Biblical Literature.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22148-3.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge.

- Le Strange, Guy (1890) Palestine under the Moslems: a description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500; Reprinted by Khayats, Beirut, 1965, ISBN 0-404-56288-4

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Levy, Thomas E. (1998). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing. LaBianca, Øystein S.; Younker, Randall W. "The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (c. 1400–500 CE)". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns.

- Lipschits, Oded, et al., eds. (2006). Judah and the Judeans in the 4th century BCE. Eisenbrauns. Kottsieper, Ingo. "And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit". Missing or empty

|title=(help) Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David. "Yehud Stamp Impressions in the 4th century BCE.". Missing or empty|title=(help) - Maniscalco, Fabio (2005) Protection, conservation and valorisation of Palestinian Cultural Patrimony, Massa Publisher. ISBN 88-87835-62-4.

- Masterman, E. W. G. (1903): The Jews in Modern Palestine

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- McCarthy, Justin (1990) The Population of Palestine. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07110-8.

- Merrill, Eugene H. (1995). "The Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Transition and the Emergence of Israel". Bibliotheca Sacra 152 (606): 145–62.

- Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

- Miller, Robert D. (2005). Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries BC. Eerdmans.

- Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Parfitt, Tudor (1987) The Jews in Palestine, 1800-1882. Royal Historical Society studies in history (52). Woodbridge: Published for the Royal Historical Society by Boydell.

- Pitkänen, Pekka (2004). "Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement" (PDF). Tyndale Bulletin 55 (2): 161–82.

- Rogan, Eugene L. (2002) Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850-1921. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-89223-6.

- Sicker, Martin (1999) Reshaping Palestine: from Muhammad Ali to the British Mandate, 1831-1922. New York: Praeger/Greenwood ISBN 0-275-96639-9

- Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B., eds. (1997). The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. Hesse, Brian; Wapnish, Paula. "Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East?". Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill.

- Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (1992). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. Cahill, Jane M. "Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy". Missing or empty

|title=(help) Lehman, Gunnar. "The United Monarchy in the Countryside". Missing or empty|title=(help) - Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press.

- Zevit, Ziony (2001). The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum.

- The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition Translated by William Whiston, Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 1987. ISBN 1-56563-167-6

| ||||||||||||||