History of music in Paris

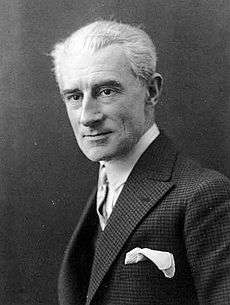

The city of Paris has been an important center for European music since the Middle Ages. It was noted for its choral music in the 12th century; for its role in the development of ballet, and as the home of the many important composers, including Frédéric Chopin, Jacques Offenbach, Georges Bizet, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Hector Berlioz and Igor Stravinsky. In the 19th century it was famous for its music halls and cabarets, and in the 20th century for the first performances of the Ballets Russes, its jazz clubs, and its part in the development of serial music.

Music of medieval Paris

The Cathedral schools and choral music

In the Middle Ages, music was an important part of the ceremony in Paris churches and at the royal court. The Emperor Charlemagne had founded a school at the first cathedral of Notre Dame in 781, whose students chanted during the mass; and the court also had a school, the schola palatina, which traveled wherever the imperial court went, and whose students took part in the religious services at the Royal Chapel. Large monasteries were founded on the Left Bank at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Victor, which taught the art of religious chanting, adding more elaborate rhythms and rimes. When the new Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris was constructed, the Notre Dame school became famous for its innovations in vocal counterpoint, or polyphony. The Archdeacon Albert of the Notre Dame school became famous for composing the first known work for three voices, each chanting a different part at the same time. Another famous teacher at the Notre Dame school, Pérotin, composed for four different voices, with highly complex rhythms, blending all the voices together in ways never heard before. In the 13th century, the monks of the Notre Dame school developed an even more complex form, the motet, or "little word"; short pieces for two or three voices, each chanting different words, and sometimes in different languages. The motet became so popular that it was used in non-religious music, in the court and even by musicians and singers on the streets. [1]

A second important music school was established at the Sainte-Chapelle, the royal chapel on the Île de la Cité. Its choir had twenty-five persons, both men and boys, who were taught chanting and vocal techniques. The music of the religious schools became popular outside the churches; the melodies of chants were adapted for popular songs, and sometimes popular song melodies were adapted for church use.[2]

One of the most famous Paris composers of 14th century was Guillaume de Machaut, who was also renowned as a poet. He composed a famous mass, the Messe de Nostre Dame, or Mass of our Lady, in about 1350, for four voices. Besides church music, he wrote popular songs in the style of the troubadours and trouvères.[3]

Street singers and Minstrels

The crowds on the streets, squares and markets of Paris were often entertained by singers of different kinds. The goliards were non-conformist students at the religious colleges, who led a bohemian life, and earned money for food and lodging by reciting poems and singing improvised songs, either love songs or satirical songs, accompanying themselves on medieval instruments, usually the trivium or the quadrivium. The trouvéres sang popular songs, romances or humorous, largely borrowed in style and content from the troubadours of southern France. They often entertained crowds gathered on the Petit Pont, the bridge connecting the Île de la Cité with the left bank. They introduced a particular form, the rondeau, a round song. The Jongleurs were famous for burlesque songs, making fun of the merchants, clergy, and the nobility. Some of them became immensely popular, and received lodging and gifts from the nobles they amused.

The Menestrels, (Minstrels), were usually street singers who had established a more professional means of living, entertaining in the palaces or residences of noble and wealthy Parisians. In 1321, thirty seven minstrels and jongleurs formed a professional guild, the Confrérie de Saint-Julien des ménétriers, the first union of musicians in Paris. Most of them played instruments: the violin, flute, hautbois, or tambourine. They played at celebrations, weddings, meetings, holiday events, and royal celebrations and processions. By their statutes enacted in 1341, no musician could play on the streets without their permission. In order to become a member, a musician had to be an apprentice for six years. At the end of the six years, the apprentice had to audition for a jury of master musicians. By 1407, the rules of the Confrérie were applied to all of France. [4]

Musicians were also an important part of court life. The court of Queen Anne of Brittany, wife of Charles VIII of France, in 1493 included three well-known composers of the period: Antonius Divitis, Jean Mouton, and Claudin de Sermisy, as well as a tambourine player, a lute player, two singers, a player of the rebec (a three-stringed instrument like a violin), an organist, and a player of the manichordion, as well as three minstrels from Brittany. [5]

Links to music

- Listen to a Medieval motet in three voices from the School of Notre Dame

- Listen to the Mass of Notre Dame in four voices by Guillaume de Machaut

Music of Renaissance Paris (16th century)

At the death of Charles VI in Paris in 1422, during the devastating Hundred Years' War which ended in 1453, the city had been occupied by the English and their Burgundian allies since 1418. The new (disinherited) French king, Charles VII, had his court established in Bourges, south of the Loire Valley, and did not return to his capital before liberating it in 1436. His successors chose to live in the Loire Valley, and rarely visited Paris. However, in 1515, after his coronation in Reims, king Francis I made his grand entrance in Paris and, in 1528, announced his intention to return the royal court there, and began reconstructing the Louvre as the royal residence in the capital. He also imported the Renaissance musical styles from Italy, and recruited the best musicians and composers in France for his court. La Musique de la Grande Écurie ("Music of the Great Stable") was organized in 1515 to perform at royal ceremonies outdoors. It featured haut, or loud instruments, including trumpets, fifes, cornets, drums, and later, violins. A second ensemble, La musique de la Chambre du Roi ("Music of the King's Chamber") was formed in 1530, with bas or quieter instruments, including violas, flutes and lutes. A third ensemble, the oldest, the Chapelle royale, which performed at religious services and ceremonies, was also reformed on Renaissance models. [6]

Another important revolution in music was brought about by the invention of the printing press; the first printed book of music was made in 1501 in Venice. The first printed book of music in France was made in Paris by Pierre Attaingnant; his printing house became the royal musical house in 1538. After his death, Robert Ballard became the royal music printer. Ballard established a shop in Paris in 1551. The most popular musical instrument for wealthy Parisians to play was the lute, and Ballard produced dozens of books of lute songs and airs, as well as music books for masses and motets, and pieces from Italy and Spain. [7]

The most popular genre in Paris was the chanson; hundreds were written on love, work, battles, religion and nature. Mary, Queen of Scots and wife of King King Francis II wrote a song of mourning for the loss of her husband, and French poets including Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay had their sonnets and odes put to music. The most popular composers of songs included Clément Janequin, who wrote some two hundred and fifty pieces, and became court composer for the King, and Pierre Certon, who was a cleric at Saint-Chapelle while he wrote some three hundred chansons, ranging from religious and courtly music to popular melodies, such as the famous Sur le Pont d'Avignon. In the second part of the century a variation of the chanson, the air de cour or simply air, became popular. Airs were lighter in subject, and were accompanied by a lute. They became immensely popular in Paris.[8]

The Reformation and religious music

The movement of Protestant Reformation, led by Martin Luther in the Holy Roman Empire and John Calvin in France, had an important impact on music in Paris. Under Calvin's direction, between 1545 and 1550 books of psalms were translated from Latin into French, turned into songs, and sung at reformed services in Paris. The Catholic establishment reacted fiercely to the new movement; the songs were condemned by the College of Sorbonne, the fortress of orthodoxy, and in 1549, one Protestant tailor in Paris, Jacques Duval, was burned at the stake, along with his song book. When the campaign against the new songs proved ineffective, the Catholic Church, at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which launched the Counter-Reformation, also launched a musical counter-reformation. It was calling for an end to complex but unintelligible chants, simpler melodies, and more serious and elevated lyrics.[9]

Music and the first theater companies

The beginning of the 16th century saw the first theater performances in Paris, which frequently included music and songs. An amateur theater group called the Confrérie de la Passion was periodically performing Passion Plays, based on the Passion of Jesus, in a large hall on the ground floor of the Hospital of the Trinity on Rue Saint-Denis, where they remained until 1539. In 1543 they bought one of the buildings attached to the hôtel de Bourgogne at 23 rue Étienne-Marcel, which became the first permanent theater in the city. The church authorities in Paris denounced Passion and religious mystery plays, and they were banned in 1548. The Confrérie rented out its theater to visiting theater troupes, notably an English company directed by Jean Sehais, an Italian company called the Gelosi Italiens, and a French company headed by Valleran Le Conte. [10]

New instruments and the guild of instrument-makers

The Renaissance saw a great increase in the number and quality of musical instruments; the harp, violin and flute were produced with many new variations; the seven-string guitar appeared, and the lute, which was based on the oud, an Arab instrument brought to the Iberian Peninsula during the Moorish invasions. The trumpet evolved to something similar to its present form. Powerful organs were built for Paris churches, as well as smaller portable organs and the clavichord, ancestor of the piano. The lute, most often used to accompany songs, became the instrument of choice for minstrels and musically-inclined aristocrats. In 1597 there were so many different instrument-makers in Paris that they, like the minstrels, were organized into a guild, which required six years of apprenticeship and the presentation of a master-work to be accepted as a full member. [11]

Dance and ballet

Dance was also an important part of court life. The first French book of dance music was published in 1531 Paris, with the title: "Fourteen gaillardes, nine pavanes, seven branles and two basses-danses". These French dance books, called Danceries, were circulated all over Europe. The names of the composers were rarely credited, with the exception of Jean d'Estrée,[12] a member of the royal orchestra, who published four books of his dances in Paris between 1559 and 1574.

At the end of the 16th century, the ballet became popular at the French court. Ballets were performed to celebrate weddings and other special occasions. The first performance of Circé by Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx was performed at the Louvre Palace on September 24, 1581, to celebrate the wedding of Anne de Joyeuse, a royal favourite of Henry III, with Marguerite de Vaudémont. [13] Ballets at the French royal court combined elaborate costumes, dance, singing, and comedy. During the reign of Henry IV, ballets were often comic or exotic works; those performed during his reign included "The Ballet of the fools", "The Ballet of the drunkards", "The Ballet of the Turks", and "The Ballet of the Indians". [14]

Links to music (16th century)

- Listen to Song of the birds by Clement Janequin

- Listen to the song Je n'ose le dire by Pierre Certon

17th century - royal court music, ballet and opera

_(14779363671).jpg)

In the 17th century, music played an important part at the French royal court; there was no day without music. Louis XIII composed songs, and in 1618 organized the first permanent orchestra in France, called La Grande Bande or the Twenty-four ordinary violins of the King, who performed for royal balls, celebrations, and official ceremonies. His son, Louis XIV, was also an accomplished musician, taught the guitar and the harpsichord by the most accomplished musicians of the period. Under Louis XIV, Jean-Baptiste Lully was invited from his native Florence and became the court composer, Under Lully, music became not simply entertainment, but an expression of royal majesty and power.[15]The royal ministers, Cardinals Richelieu and Mazarin encouraged the development of French music in place of the Italian style.[16]

In the homes of the nobility and wealthy families, the children, both boys and girls, were taught to sing and to play musical instruments, including the harp, flute, guitar and harpsichord, either in the convent schools and at home, with private tutors. Louis XIV established the Royal Academy of Music in 1672, and ordered Lully to create a music school, but a school for opera singers in Paris was not opened until 1714, and its quality was very poor; it closed in 1784. [17] One notable music teacher and composer was Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, the harpsichord teacher of Louis XIV, whose compositions established the French school of harpsichord music.

The Air de Cour, or Court Air, became very popular in the early 17th century, during the reign of Louis XIII, both at the royal court and in the homes of the nobility and wealthy. It was designed to be sung in the large bedrooms where the nobility often entertained their intimate friends, and were usually improvised songs on the themes of gallantry and love, in the form of a dialogue, performed with the lute and the théorbe. The composer Pierre Guéron, music teacher to the children of the King, published several books of court airs, and trained Angélique Paulet, the most famous Parisian singer of the early 17th century. The published songs were learned and sung by both nobles and wealthy Parisians. [18]

The debut of French opera

Cardinal Mazarin, raised in Rome, was an enthusiastic supporter of Italian culture, and imported Italian painters, architects and musicians to work in Paris. In 1644, he invited the castrato Atto Melani to Paris, along with his brother Jacopo and the Florentine singer Francesca Costa, and introduced the Italian singing style to Paris. The Italian style was much different than the French style of the day; voices were stronger and the singing expressed stronger emotions, rather than the finesse of the classical French style.[19] The following year the first performance of an Italian opera was given in Paris; La Finta Pazza by Marco Marazzoli, at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal on February 28, 1645, followed in 1647 by the more famous Orfeo of Luigi Rossi at the Petit-Bourbon theater next to the Louvre.[20]

The debut of Italian opera in Paris had exactly the opposite effect that Mazarin desired. Paris audiences were not prepared for a theatrical work that was entirely sung. Furthermore, the Cardinal was denounced and ridiculed by Parisian streets singers and pamphlets called Mazarinades for spending a fortune on opera decoration and bringing Italian castrati and singers to Paris. Barricades went up in the streets, the uprising, called the Fronde, spread, and Mazarin was forced to leave Paris for a time. When calm was restored, he returned to Paris and continued his project to install opera in Paris. At the time the city had no theater to rival the opera houses of Venice or Rome; in 1659 Mazarin began construction of Salle des Machinesa new theater just to the north of Tuileries Palace, between the Marsan Pavilion and the chapel. It could seat six thousand persons. had marble columns, was lavishly decorated, and contained the elaborate machinery needed to produce dramatic stage effects. Mazarin's death delayed the opening, but it was finally inaugurated in 1662 with an Italian opera, l'Ercole amante, by Cavalli. The premiere was a disaster; the acoustics in the new hall were terrible, and the sound of the stage machinery drowned out the music. [21]

The efforts to create a French opera continued; the poet Pierre Perrin persuaded the new chief minister of the government, Colbert, to establish an Academy of Opera, and in 1669 Perrin was given a commission by the King to create works "in music and in French verse comparable to that of Italy." The first opera by Perrin, Pomone, with music by Robert Cambert, was performed on March 3, 1671, inside a converted Jeu de Paume, or tennis court, between the rue des Fosses-de-Nesles and the rue de Seine. It was an enormous success, running for one hundred forty-six performances. Seeing the success of Perrin's work, the official court composer, Lully, moved quickly; he persuaded royal government to issue a decree banning any theatrical performances with more than two songs or two instruments without Lully's written permission. Lully also asked and received permission to Lully quickly took over all the production of operas in Paris. In 1671 alone, Lully wrote and presented five new operas. On November 15, 1672, Lully opened his own opera house in the Jeu-de-Paume court of Bel-Aire. Lully also demanded and received from the King the exclusive rights to use the theater of the Palais-Royal, until then used by the theater company of Moliere, giving him control over any and all musical performances in Paris. He presented a new opera each year, entirely funded by the royal treasury. Shortly afterwards, he premiered Cadmius et Hermione, the first French opera in the lyric-tragedy form. This form, which dominated French opera for tw centuries but was rarely exported, featured stories based on mythology and ancient heroes. The performances made maximum use of machinery, allowing the creation on-stage of storms, monsters, and characters descending or ascending into the heavens. The texts involved recitation of verse in a classical half-spoken, half-sung style, borrowed from Racine and Corneille, with a vocal range of an octave, words mingled with sighs, exclamations and vibrato.The works included not only singing, but also dance. The operas were all dedicated to the glory of the King; in the dedication of Armide, Lully wrote, "All of the praises of Paris are not enough for me; it is only to you, Sire, that I want to consecrate all the productions of my genius." [22]

After 1672, Louis XIV no longer resided in Paris, living instead at Saint-Germain, Chambord, Fontainebleau and Versailles; and in 1682 he moved his residence permanently to Paris. The royal musicians and opera singers went with him, and Versailles, not Paris, became the center of French musical life.

Ballet

During his residence in Paris, the young Louis XIV was an avid dancer and participant in ballet. Ballet was commonly practiced by young nobles, along with fencing and horsemanship. Only men danced, except in those ballets given by the ladies of the Queen. Louis practiced several hours a day, and made his first ballet appearance in the Ballet de Cassandre at the age of thirteen. He was featured in the Ballet Royal de la Nuit, at the Petit-Bourbon theater, on 23 February 1653. This court ballet lasted 12 hours, beginning at sundown and lasting until morning, and consisted of 45 dances. Louis XIV appeared in 5 of them. The most famous dance of Ballet Royal de la Nuit saw Louis XIV appear as Apollo the Sun King, as the Soleil levant ("rising Sun") . [23][24]

With the arrival of the twenty-six year old Jean-Baptiiste Lully at the court, the ballet began to take on a new dimension. Lully premiered his first Grand Ballet Royal, Alcidiane on February 14, 1658, with the entire court in attendance. The performance lasted several hours, and was composed of seventy-nine different tableaux, or scenes. In the 1660s Lully evolved the performances into a combination of ballet, singing, and theater. The performance of Moliere's comedy "The Forced Marriage"at the Louvre in 1644 included not only scenes by Moliere and his actors but also several ballets and also songs by the leading singers of the day, Mademoiselle Hilaire and Signora Anna. However, in 1670, at the age of twenty-six, Louis XIV decided to give up dancing. As a result, the Lully revised the format of the court ballets to please the King as a spectator, rather than dancer. For his new ballet, Psychée, performed before the King on January 17, 1671, the performance included ballet, singing, acting, orchestral music, and immense visual spectacles created by stage machinery. At one point in the performance, three hundred performers were on or suspended above the stage, singing, dancing, or playing lutes, flutes, trumpets, cymbals violins, the harpsichord, the hautbois and the théorbe. [25]

Religious music

Music was also seen as an important weapon of the Counter-Reformation, along with Baroque art, to win ordinary people to the side of the Catholic Church. Under the new doctrine, music was given a larger role in religious services. Sainte-Chapelle was famous for the purity and beauty of its music, while the Te Deum chanted at Notre-Dame was famous for its soloists, choirs and double-choirs, and for the musical form called the motet created for the cathedral's singers. Special music was written for the service called The churches were equipped with magnificent organs. The organists of Paris churches were often members of families who held the post for generations; the most famous were the Couperin family, who were organists at the church of St-Gervais-et-St-Protais near the Louvre from 1650 until the French Revolution. The most famous member of the family was François Couperin, who composed and published numerous pieces, both religious and secular, for the organ and harpsichord. The dynasties included several famous women who made their mark on Parisian music; Louise Couperin, the daughter of Franois, was a famous singer, and his granddaughter Marguerite became the first woman harpsichordist attached to the royal orchestra. Elisabeth Blanchet, the daughter of a prominent Paris harpsichord maker and the wife of Armand Couperin, often took the place of her husband at the organs of Saint-Gervais, Sainte-Chapelle and Notre Dame. Her daughter Céleste also became a noted Paris organist at Saint-Gervais. [26]

Street musicians and comic opera

-

Muscians at home, by Abraham Bosse (about 1632)

-

The Pont Neuf was the most popular venue for street singers and musicians (painting by Hendrick Mommers, 1694)

-

.jpg)

Tabarin, his actors and musicians perform on Place Dauphine (17th century)

-

Guillaume de Limoges, the ribald street singer called the "Lame Lothario" on the Pont Neuf (17th century)

The most popular gathering place for street musicians and singers, as well as clowns, acrobats and poets, was the Pont Neuf, inaugurated by Louis XIII in 1613. All the carriages of the aristocracy and the wealthy crossed the bridge, and since it was the only bridge not lined by houses, there was room for a large audience. Listeners could hear comical songs about current events, romantic poems set to music, and (after 1673), the latest melodies of the court composer, Lully. Philipotte, the "Orpheus of the Pont-Neuf", Duchemin, "The Choir boy of the Pont-Neuf", and the one-legged Guillaume de Limoges, the "Lame Lothario", known for his ribald songs, were famous throughout Paris. The celebrated bateleur Tabarin set up a small stage on Place Dauphine, at the point where the bridge crossed the Île-de-la-CIté; his company presented theater, songs and comedy. Between acts his business partner sold medicines and ointments. [27]

The debuts of each 0f the lyric-tragic operas of Lully were followed almost immediately by parodies performed on the stages at the large outdoor fairs of Paris, at Saint-Germain and Saint-Laurent. A large stage was constructed at the Saint-Germain Fair in 1678. The Academy of Music moved quickly to have the city ban recitation of text on stage, which was the exclusive right of the Comedie-Française and the Royal Academy of Music. The actors at the Fairs responded by writing their dialogue on signs and holding them up, where the audience read them aloud. The singers sometimes also sang with unintelligible words, mimicking the formal court style of Lully's music. The performers at the fairs invented a new style which combined comic songs with satire, and acrobatics, a form which took the name vaudeville. [27]

The foundation of the Royal Academy of Music in 1672 created a growing gulf between the official musicians of the court and the popular musicians of Paris, who were members of the guild of ménétriers, or minstrels, with its own rules and traditions, under their traditional head, the elected "King of the Minstrels". While the guild of minstrels had a monopoly over the music in the streets, Lully, the head of the royal academy, had an ordnance passed which gave academy members the exclusive right to play at balls, serenades, and other public events. Academy members did not have to go through the apprenticeship required to be a member of the minstrels guild. The guild of minstrels brought a lawsuit against François Couperin and the other organists of Paris churches, demanding that they join the minstrels guild. The guild won the lawsuit, but the organists appealed to the Parliament of Paris, which exempted them from the rules of the Guild. The Guid nonetheless continued to exist until the Revolution; in 1791, it was quietly dissolved.[28]

Links to music (17th century)

- Listen to songs of the French Royal Court from the 17th century

- Listen to "March for the Turkish Ceremony" by Jean-Baptiste Lully

- Watch a ballet from the opera Armide by Lully (1686)

- Listen to an organ work by François Couperin (1690)

18th Century - The Opera, the Comic Opera, and the Salon

The musical life of Paris at the beginning of the 18th century was gloomy; the court was at Versailles, and frivolity was officially frowned upon by the King and his companion, Françoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, and the religious party at court. The King's favorite composer, Lully, fell into disgrace because of his unorthodox lifestyle. Musical satires and farces continued to be sung on stages at the Fairs, but they were constantly under attack from the Academy of Music, which claimed a monopoly on singing performances. The Théâtre-Italien troupe was forced to leave Paris because of accusations that they made fun of the King's companion. After the death of the King in 1715, the Regent and Court returned to Paris, and the musical world brightened.

The Opera

_-_001.jpg)

The opera continued to create lavish productions of lyrical tragedies, in the style of Lully. In 1749, the management of the opera was transferred from the court to the city of Paris, much to the dismay of city authorities, who had to pay for the huge spectacles. The opera performed at the theater of the Palais-Royal until April 6, 1763, when a fire destroyed that venue. It moved to the Hall of Machines of the Tuileries, then back to the Palais-Royal in 1770 when the theater was rebuilt. It burned down again in 1781. After Lully, the lyric-tragedy style of opera was faithfully maintained by a series of composers, the most prominent of whom was jean-Philippe Rameau, who arrived in Paris from Dijon in 1723 and premiered his first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie, in 1733. The Mercure de France, the first Paris newspaper, described his music as "manly, harmonious, and of a new character" different from the music of Lully. The musical world of Paris soon divided into Lullyists and Rameauneurs, as they were termed by Voltaire. The prolific Rameau produced not only lyrical tragedies, but also opera-ballets, pastorales, and comic ballets. [29]

By the 1750s, Paris audiences were beginning to tire of the formality, conventions, repetitive themes, mechanical tricks and great length of the lyrical tragedies. The Enlightenment had begun in France, and critics demanded a new form of opera that was more natural. The battle was launched by the first performance in 1752 of La Serva Patrona, a 1733 Italian opera by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi at the Academy by the company of Bouffons. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau praised the Italian opera for its simple plot, popular characters, and melodic singing. Describing the quarrel in his Confessions, Rousseau wrote: "on the one side, the most powerful and influential, were the rich, the nobles, and women, supporting the French style; on the other side, more lively, more proud, and more enthusiastic, were the the true connaisseurs, the people of talent, the men of genius". [29] Rameau defended his music: "Do you not know that music is a physical-mathematical science, and that sound is a physical object, and that the relationships between the different sounds are made by mathematics and geometry?" Roussau responded that music was the language of feelings; "from the melody comes all the power of music over the human spirit." To illustrate his point, Rousseau wrote a text for a new one-act opera, Le devin du village ("The village soothsayer), about the love of two simple peasants, which became part of the Academy repertoire for the next sixty years. Over the course of the 18th century, the heroic style of Lully and Rameau quietly disappeared from Paris stages, replaced by the more natural and more romantic Italian style. [29]

Another operatic feud began with the arrival of the German composer Christoph Willibald Gluck in Paris in 1776. He had already written a series of successful Italian operas. In Vienna he had studied French and had been the music teacher of the young Marie Antoinette. He staged the opera Iphigénie en Aulide in Paris, which became a huge popular triumph; he followed it with a French version of Orfeo ed Euridice, which he had written in Vienna in 1762, and then Alceste, reviving the classical lyrical tragedy style. The supporters of Italian opera responded by bringing the Italian opera composer Niccolo Piccinni to Paris in 1776. The rival new operas written by Gluck and PIccinni did not please the fickle Parisian audiences, and both composers left Paris in disgust. By the time of the Revolution the repertoire of the Paris opera consisted of five operas by Gluck, and those of Piccinni, Antonio Salieri, Sacchini and Gretry. Rameau and the French classical style had almost disappeared from the repertoire. [30]

The Fairs and the Opéra-Comique

Throughout the 18th century, the stages of the largest fairs, the Foire Saint-Germain and Foire Saint-Laurent were the places to see popular entertainment, pantomime and satirical songs. They were only open for a short period of time each year, and were strictly controlled by the rules of the Royal Academy of Music. In 1714-15, the Academy was short of money, and decided to sell licenses to producers of popular theater. The Comediens-Italiens, a troupe which had been expelled from Paris under Louis XIV, were invited back to Paris to perform satirical songs and sketches on the stage at the Hotel de Bourgogne. In 1726, a new company, the Opéra-Comique, made up of performers from the Saint-Germain fair, was formed. It first settled near the fair on rue de Buci, then moved to the dead-end street of the Quatre-Vents. Some of the most famous popular French singers of the period and the playwright Charles-Simon Favart made their debut there. In 1744 the Opéra-Comique was taken over by an ambitious new director, Jean Monnet, who built a new theater at the Saint-Laurent fair, with decorations by the famed artist François Boucher, and an orchestra of eighteen musicians conducted by Jean-Philippe Rameau. In 1762, the two competing comic opera theaters were merged under a royal charter, and were allowed to perform all year long, not just during the fairs. The two groups first performed independently on the stage at the Hotel de Bourgone, and engaged the best composers of the time, including Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny, François-André Danican Philidor and André Grétry. In 1783, they built a brand-new theater, between rues Favart, Marivaux, and the future boulevard des Italiens. The new theater, called the Salle Favart, opened on April 28, 1783, in the center of what soon became the city's main theater district. [31]

Salons

Much of the musical activity of the city took place in the salons of the nobility and wealthy Parisians. They sponsored private orchestras, often with a combination of both professional and amateur musicians, and commissioned works commissioned works, and organized concerts of very high quality, often with a mixture of both professional and amateur musicians. Some very wealthy Parisians built small theaters within their homes. In 1766, Louis François, Prince of Conti hosted a reception in his home where the featured attraction was the ten-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the keyboard. A musical society was organized by the Marquise e de Prie, the mistress of the Duke of Bourbon, which gave concerts of Italian music twice a week at the Louvre. The sixty-odd members who attended paid an annual fee, which went to the musicians. Though private individuals were forbidden to hold concerts without the permission of the Royal Academy of Music, a wealthy Parisian named Monsieur Bouland had a theater within his house on rue Saint-Antoine with a stage for two actors, an orchestra of twenty, and seating for three hundred. The Owners of salons invited not only classical musicians; they also sometimes invited popular singers of comic opera from the Paris Fairs, such as Pierre Laujon and Charles Collé, who became quite wealthy.

The Masonic movement became immensely popular among the Parisian upper classes; the first lodge opened in Paris in 1736, and had four famous musicians among its first members. By 1742, there were more than twenty, each with its own musical director. One of the most famous concert societies was the Concert Spirituel, created in 1725, which organized public concerts of religious music in Latin, and later Italian and French, in a salon within the Tuileries Palace provided by the King. Attendees at the concerts included the Queen, Marie Antoinette. The society commissioned works of music by important composers; including Hayden and Mozart, who wrote and performed two symphonies (The Parisian symphonies, K. 29) for the Society during his visit to Paris in 1778. In 1763 the society moved to the Hall of Machines, and had an orchestra fifty-four musicians and vocal ensemble of six sopranos, six tenors and six basses. [32]

Popular music and street singers

The most popular venues for popular music, satire and comic songs continued to be the stages at the major fairs, where crowds listened to satirical, comical and sentimental songs, though they were only open part of the year. in 1742, the royal government decided that the street singers on the Pont-Neuf were a public nuisance, and were blocking traffic. Only booksellers were allowed to remain, and they had a pay a fee to the royal government. The street and popular musicians migrated across town to the Boulevard du Temple, a wide street with vestiges of the old city walls on one side, and houses on the other. In 1753 the city authorized the construction of cafes and theaters, at first made of canvas and wood, along the boulevard; and the boulevard quickly became the center of popular theater of Paris, a position it held until the Second Empire. [33]

Public Balls

Public balls were banned on moral grounds during the last years of the reign of Louis XIV, and were not permitted again until after his death in 1715. At this time a royal ordinance of 31 December 1715 authorized the first public balls in the city. These were the famous masked balls of the Paris Opera, which took place on Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays beginning on St. Martin's Day (November 11) and continuing until Carnival (February–March).

Links to music (18th century)

- Watch Hippolyte et Aricie by Jean Philippe Rameau (1733)

- Listen to Mozart's Symphony number 31 (The Paris Symphony), written for the Concert Spirituel

- Listen to French popular music from the 18th century

- Listen to a song by André Grétry from the Paris Opéra-Comique (1788)

The music of revolutionary Paris (1789-1800)

Patriotic and revolutionary songs gave, as one journal of the period, the Chronique de Paris, wrote, "The national color to the Revolution". [34] They were sung at political meetings, in theaters, in schools and on the streets. The most popular revolutionary songs were the Carmagnole (about 1792); with words by an anonymous author, and music from an existing song; and Ça ira with words by de Ladré and the music of an old contredanse by the violinist Bécaut called Le Carillon national. The song took its title from an expression, "That will happen," which Benjamin Franklin, the American envoy to Paris had popularized, describing the American Revolution. The most famous song of the period was the Chant de guerre pour l'armée du Rhin (Battle Song of the Army of the Rhine), by a young army officer, Claude Rouget de Lisle. it was first sung in public 30 July 1791 by a battalion of volunteers from Marseille as they marched into Paris, and thereafter became known as the Hymne des Marseillais, which became, on August 10, 1792, the official anthem of the Revolution. During the revolutionary period, ''Ça ira was played by the orchestra in every theater before a performance, with the audience and performers singing. The Marseillaise was always performed at the intermission. Often the songs were sung during the performances, if the audience demanded it. In 1796, the government of the Directory made the singing of such songs obligatory for all theaters, while banning the singing of songs by other political factions, such as the Reveil du people (Wake-up call of the People), the song of the Thermidorians. [35]

Music was also an important ingredient of the enormous public festivals that were organized by the Revolutionary governments, usually on the Champ-de-Mars, which was transformed into an enormous outdoor theater to host these spectacles. The first was the Fete de la Federation on July 14, 1790, marking the first anniversary of the taking of the Bastille. The Fetes began in the morning with the ringing of church bells and firing of cannons; patriotic songs were sung throughout the ceremonies; and they always concluded with a concert by the musicians of the National Guard and a ball in the streets. The last of the great festivals was the Festival of the Supreme Being, organized on June 8, 1794 by Robespierre as a substitute for traditional religious celebrations; it had singers and choirs surrounding an artificial mountain crowned by the Tree of Liberty. Robespierre's role in the event did not entirely please the audience; he was arrested and executed a few weeks later.

Founding of the Conservatory

The flight of the aristocracy from Paris had created an enormous number of unemployed musicians and music teachers. The growing number of public concerts and ceremonies required a greater number of trained musicians, particularly for the orchestra and band of the Garde Nationale, which had been formed in June 1790 to perform at the Festival of the Federation on the Champs-de-Mars. Bernard Sarrette, a captain of the National Guard, founded a school to train eighty young musicians, who at first were taught only wind instruments. It was given the name the Institut National de Musique, and was the first national music school in France. The teachers were leading musicians and composers of the period. The Revolutionary Committee of Public Safety instructed the new music school to concentrate on the composition of "civic songs, music for national festivals, theater pieces, military music, all types of music which will inspire in Republicans the the sentiments and memories most dear to the Revolution." [36]

In 1792 the revolutionary government decided to create a larger and more ambitious school of music, which would teach all instruments and genres of music. It was named the Conservatoire National de musique, using the name Conservatory, an Italian Renaissance institution much praised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It became the first music conservatory in France. with 350 students, both male and female, from all forty-six departments of France. The instruction was creel the 115 music teachers were paid by the state. The Institute, in the meanwhile, collected the musical instruments and musical libraries of the thousands of aristocrats who had fled France, and put them in a central depository for the use of students. The Conservatory opened its doors in 1796.[35]

Musical theater and the opera

_1829.jpg)

Despite the turmoil of the Revolution (or perhaps partly because of it) musical theater thrived during the period. New theaters appeared; the Théâtre du Vaudeville, the Palais-Variétes and the Théâtre Feydau. The Feydau theater featured both a troupe performing French comic operas, and another performing Italian comedies. A half-dozen new theaters on the Boulevard du Temple, the new theater district of the city, performed vaudeville, pantomime and comic opera. The actress Madamoiselle Montansier opened her own musical theater in the Palais-Royal. The great fair of Saint-Germain, was closed by the Revolution, but a new theater, the Théâtre Lyrique du Saint=Germain, opened on its old site in 1791. Seventy-six new comic operas or vaudeville programs were staged in 1790, and fifty new works in each of the following years. Censorship of theatrical works was abolished in 1791, but this freedom did not last long. In 1793 the Committee of Public Safety decreed that any theater which put on plays "contrary to the spirit of the Revolution" would be closed and its property seized. After this decree, musical works on patriotic and revolutionary themes multiplied in the Paris theaters. [37]

The opera itself, a symbol of the aristocracy, was officially taken away from the former Royal Academy and given to the city of Paris in 1790. When the Terror began in 1793, one of its two new directors fled abroad, and the second was arrested, and only escaped the guillotine because Robespierre was executed first. The opera prices were reduced, and special free performances were given for the poor. The program at both the Opera and the Opera-Comique were largely patriotic, Republican and sometimes anti-religious. At the same time, operas by Lully and Gluck were still performed, though sometimes new lyrics were added attacking the King and monarchy. In March 1793, in the midst of the terror, Parisians heard their first Mozart opera, The Magic Flute, in French and without the recitatives. The opera was forced to move from its theater at Porte Saint-Martin in 1794 to the Salle Montansier at the Palais-Royal so the government could use the theater for political meetings. The Opera saw its name changed from the Academie Royal de musique to the Théátre de l'Opéra (1791) to the Théátre des Arts (1791) to the Théátre de la Republique et des Arts (1797). the Théátre de l'Opéra again in 1802, then, under Napoleon, to the Academie Imperial (1804). [38]

Pleasure gardens, cafés chantants and guinguettes

During the late 18th century, and particularly after the end of the Reign of Terror, Parisians of all classes were in constant search for entertainment. The end of the century saw the opening of the pleasure gardens of Ranelegh, Vauxhall, and Tivoli. These were large private gardens where, in summer, Parisians paid an admission charge and found food, music, dancing, and other amusements, from pantomime to magic lantern shows and fireworks. The admission fee was relatively high; the owners of the gardens wanted to attract a more upper class clientele, and keep out the more boisterous Parisians who thronged the boulevards.

With the closure of the fairs by the 1789 Revolution, the most popular destination for musical entertainment became Palais-Royal. Between 1780 and 1784, the duc de Chartres, (who became the Duke of Orleans in 1785 at the death of his father), rebuilt the garden of the Palais-Royal into a pleasure garden surrounded by wide covered arcades, which were occupied by shops, art galleries, and the first true restaurants in Paris. The basements were occupied by popular cafés with drinks, food and musical entertainment, and the upper floors by rooms for card-playing. The first famous musical café was the Café des Aveugles, which had an orchestra and chorus of blind musicians. In it early days it was popular with visitors to Paris, and also attracted prostitutes, trinket-sellers and pickpockets. Later cafés in the Palais Royal, named cafés chantants, offered musical programs of comic, sentimental and patriotic songs.[39]

The guinguette was mentioned as early as 1723 in the Dictionnaire du commerce of Savary. It was a type of tavern located just outside the city limits, where wine and other drinks were much cheaper and taxed less. They were open Sundays and holidays, usually had musicians for dancing, and attracted large crowds of working-class Parisians eager for rest and recreation after the work week. As time went on, they also attracted middle class Parisians with their families.[40]

Links to songs of the French Revolution

- Listen to the Revolutionary song Ça ira

- Listen to La Carmagnole

- Listen to the Marseillaise, with English translation

Music during the First Empire (1800-1814)

During the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul and then Emperor, music in Paris was used to celebrate his victories and glory. Napoleon installed his brother Lucien as chief censor in 1800, and all musical and theater works were examined by the police before being performed. The former Academy of Music became the Académie Impérial, The official composer of Napoleon's regime was Jean-François Lesueur, who wrote a heroic opera, Ossian, ou Les bardes to glorify Napoleon. It was performed more than a hundred times in Paris before Napoelon's fall. He also wrote a special march for the coronation of Napoleon as Emperor at Notre-Dame, and directed the solemn mass, Te Deum and other music performed at the coronation. Lesueur wrote new opera Le Triomphe de Trajan, to celebrate Napoleon's victories at Iéna, Friedland and Eylau. The opera had spectacular staging, with parades of soldiers and cavalry on stage. Lesueur continued his musical career after Napoleon's fall, as a professor of composition at the Conservatory; his future students included Hector Berlioz and Charles Gounod.[41]

The Empress Josephine had her own favorite composer, the Italian Gaspare Spontini, who became her official composer of both historical dramas and comedies. his first lyrical work, Le Vestal, had a considerable success. His next work, Fernand Cortez. was commissioned when Napoleon decided to invade Spain, and celebrated the conquest of Mexico by Cortez. Unfortunately, the French army was defeated in Spain and Fernand Cortez was pulled from the repertoire, but it made a great impression on other French composers with its grand scenic effects; a Mexican ballet and a cavalry charge, its use of drums, and its huge chorus. Napoleon recreated the grandeur of the old French court, constructing a new theater at the Tuileries Palace, which was finished in 1808. He also brought together an exceptional troupe of musicians and singers from Italy, including the composer Ferdinando Paër, who became master of his household music; the castrato Girolamo Crescentini, and the contralto Giuseppina Grassini. Napoleon did not allow applause in the hall during performances. The orchestra played a special air by Gretry when Napoleon entered the theater, and the Vivat Imperator when he departed. But, because of his military campaigns, he was rarely in Paris to enjoy them. [42]

Napoleon gave eight theaters official status, and to avoid competition to his official theaters, he closed all the others. The Imperial Academy and the Opéra-Comique were at the top of the hierarchy; followed by the Théâtre de lEmpereur, the new Opera Buffa of the Théâtre de l'Imperatrice, the theater of the Empress, run by Mademoiselle Montansier. Major operas and melodramas were performed at the theater at Porte-Saint-Martin and Opéra-Comique; parodies at the Vaudeville theater, and rustic comedies at the Variétés. With the signing of the Concordot between the French Empire and the Catholic church, the Paris churches were re-opened, and religious music was allowed once more.

Music during the Restoration (1815-1830)

The Opera and the Conservatory

After the final departure of Napoleon for St. Helena in 1815, the new government of Louis XVIII tried to restore the Parisian musical world to what it had been before the Revolution. The opera once again became the Royal Academy, the Conservatory was renamed the École Royal de Musique, and was given a department of new department of religious music, and the composer Luigi Cherubini was commissioned to write a grand coronation march for Louis XVIII, and later one for his successor, Charles X of France. Spontini was named the director of royal music. Lavish concerts in salons resumed in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, often given the most popular new keyboard instrument, the piano. However, the government greatly irritated ordinary Parisians by banning music and dancing on Sundays, closing the popular guingettes.

At the beginning of the Restoration, the Paris Opera was located in the Salle Montansier on Rue de Richelieu, where the square Louvois is today. On 13 February 1820, Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry was assassinated at the door of the opera, and King Louis XVIII, in his grief, had the old theater demolished. In 1820-1821 the opera performed in the Salle Favart of the Théâtre des Italiens, then in the sale Louvois on rue Louvois, then, beginning on 16 August 1821, in the new opera house on rue Le Peletier, which was built out of the material of the old opera house. It was intended to be a temporary home until a new opera house was built; it was not elegant and not well-located, but it was large and had modern lighting and stage equipment; gas lights were installed in 1822, and the first electrical lighting in 1849. It remained the primary opera venue of Paris for a half century, until the opening of the Palais Garnier.

The opera repertoire was largely familiar works of Gluck, Sacchini and Spontini, plus fresh works by new composers, including François Adrien Boieldieu, Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold, and Daniel Auber, An opera by Carl Maria von Weber, "Robin Hood", was translated into the French and presented in 1824, causing a sensation. The first of new genre of romantic and nationalist French operas, La Muette de Portici by Auber, premiered in February 1829; the hero was an Italian patriot fighting against Spanish occupation and oppression. A performance of the same opera in Brussels in 1830 led to a popular uprising and the liberation of Belgium from Dutch rule. The opera also featured grand spectacles created with ingenious stage machinery and lighting, including recreations of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the realistic illusions of flames and moving water.[43]

Rossini and the Théâtre Italien

The grand rival of the royal opera was the Théâtre-Italien, which beginning in 1819 performed at the Salle Favart. It was formally under the administration of the royal opera, but it had its own administrator and repertoire and produced only works in Italien. It presented the works of the composer Gioacchino Rossini, He staged his first work in the Paris, L'Italiana in Algiers in 1817, followed by a series of successes. He presented his most famous work, The Barber of Seville, in 1818, two years after its premiere in Rome. Rossini made modifications for the French audience, changing it from two to four acts and changing Rosina's part from a contralto to a soprano. This new version premiered at the Odéon-Théâtre on 6 May 1824, with Rossini present, and remains today the version most used in opera houses around the world. Rossini decided to settle in Paris became the musical director of the theater. With Rossini at its head, the Théâtre-Italien had a huge success; its company included several of the finest singers in Europe, including Giulia Grisi, the niece of Napoleon's favorite, Giuseppina Grassi; and Maria Malibran, whe became the most famous interpreters of the music of Rossini. After a fire burned the Salle Favart in 1838, the troupe had several homes, before it finally settled in the Salle Ventadour in 1841.

Rossini continued to produce lavish operas with spectacular sets, rapid pace, the use of unusual instruments (the trombone cymbals and triangle) and extravagant emotion. He staged Siege of Corinth (1827). then Moses and then the comic opera Le comte Ory. He then undertook to write an opera that was entirely French; he wrote William Tell based on a play by Schiller, which premiered at the Salle Le Peletier on August 3, 1829. Though the famous overture was a success, the public reception for the rest of the opera was cool; it was criticized for excessive length (four hours), a weak story, and a lack of action. Rossini, deeply wounded by the criticism, retired, at the age of thirty-seven, and never wrote another opera. [44]

Popular music - the Goguette and the political song

The musical salons of the aristocracy were imitated by a new institution; the goguette, musical clubs formed by Paris workers, craftsmen, and employees. There were goguettes of both men and women. They usually met once a week, often in the back room of a cabaret, where they would enthusiastically sing popular, comic, and sentimental songs. During the Restoration, songs were also an important form of political expression. The poet and songwriter Pierre Jean de Béranger became famous for his songs ridiculing the aristocracy, the established church and the ultra-conservative parliament. He was imprisoned twice for his songs, in 1821 and 1828, which only added to his fame. His supporters around France sent foie gras, fine cheeses and wines to him in prison. The celebrated Paris police chief Eugène François Vidocq sent his men to infiltrate the goguettes and arrest those who sang songs ridiculing the Monarch. [45]

Music in Paris under Louis Philippe (1830-1848)

Public resentment against the Restoration government boiled over in July 1830 with an uprising in the streets of Paris, the departure of the King, and the installation of the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe. Music played its part in the 1830 Revolution; the famed tenor Adolphe Nourrit, who had starred in the operas of Rossini, went onto the stages of Paris and emotionally sang the Marseillaise, which had been forbidden by the royal government during the Restoration. As Europe was upset by revolutions and repression, many of the finest musicians in the continent came to seek sanctuary in Paris.

The most famous was Frédéric Chopin, who arrived in Paris in September 1831 at the age of twenty-one, and did not return to Congress Poland because of the crushing of the Polish uprising against Russian rule in October 1831. Chopin gave his first concert in Paris at the Salle Pleyel on 26 February 1832, and remained in the city for most of the next eighteen years. He gave just thirty public performances during those years, preferring to give recitals in private salons. On 16 February 1838, he gave a concert at the Tuileries for King Louis-Philippe and the royal family. He earned his living from commissions given by wealthy patrons, including the wife of James Mayer de Rothschild, from publishing his compositions, and from giving private lessons. Chopin lived at different times at 38 rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, and at 5 rue Tronchet. He had a ten-year relationship with the writer George Sand between 1837 and 1847. In 1842, they moved together to the Square d'Orléans, at 80 rue Taitbout, where the relationship ended.

Franz Liszt also lived in Paris during this period, composing music for the piano and giving concerts and music lessons. He lived at the Hôtel de France on rue La Fayette, not far from Chopin. The two men were friends, but Chopin did not appreciate the manner in which Liszt played variations on his music. Liszt wrote in 1837 in La Revue et Gazette musicale: "Paris is the pantheon of living musicians, the temple where one becomes a god for a century or for an hour; the burning fire which lights and then consumes all fame." [46] The violinist Niccolò Paganini was a frequent visitor and performer in Paris. In 1836, he made an unfortunate investment in a Paris casino, and went bankrupt. He was forced to sell his collection of violins to pay his debts. Richard Wagner came to Paris in 1839, hoping to present his works on the Paris opera stages, with no success. Some interest was finally shown by the director of the Paris Opera; he rejected Wagner's music but wanted to buy the synopsis of his opera, Le Vaissau fantôme, to be put to music by a French composer, Louis-Philippe Dietsch. Wagner sold the work for five hundred francs, and returned home in 1842.

The French composer Hector Berlioz had come to Paris from Grenoble in 1821 to study medicine, which he abandoned for music in 1824, attending the Conservatory in 1826, and won the Prix de Rome for his compositions in 1830. He was working on his most famous work, the Symphonie Fantastique, at the time of the July 1830 revolution. It had its premiere on 4 December 1830.

The Royal Academy, Opéra-Comique and Théâtre-Italien

Three Paris theaters were permitted to produce operas; The Royal Academy of Music on rue Le Peletier; the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre-Italien, nicknamed "Les Bouffes". The Royal Academy, financed by the government, was in dire financial difficulties. In February, the government handed over management of the theater to a gifted entrepreneur, Doctor Véron, who had become wealthy selling medicinal ointments. Véron targeted the audience of the newly-wealthy Parisian businessmen and entrepreneurs; he redesigned the theater to make the loges smaller (six seats reduced to four seats), installed gas lights to improve visibility, and launched a new repertoire to make the Paris Opera "both brilliant and popular". The first great success of the new regime was Robert le Diable by the German composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, which premiered on November 21, 1831. The opera combined the German orchestral style with the Italian lyric singing style; it was an immense critical and popular success. Meyerbeer wrote a succession of popular operas, including At the end of his four-year contact, Doctor Véron retired, leaving the Opera in an admirable financial and artistic position. [47]

The Opéra-Comique also enjoyed great success, largely due to the talents of the scenarist Eugène Scribe, who wrote ninety works for the theater, put to music by forty different composers, including Daniel Auber, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Fromental Halévy (La Juive (1835)), Cherubini, Donizetti, Gounod and Verdi (for whom he wrote Les vêpres siciliennes')'. Scribe left behind the grand mythological themes of earlier French opera, and wrote stories from a variety of historical periods which, with a mixture of strong emotion, humor and romanticism, exactly suited the taste of Parisian audiences. [48]

_03_012_1_Theater_Ventadour_in_Paris_%E2%80%93_Eine_Scene_aus_dem_zweiten_Acte_des_Don_Pasquale_(cropped).jpg)

The Théâtre-Italien completed the grand trio of Paris opera houses. After the fire at the Salle Favart, it moved briefly to the Odéon Theater and then permanently to the Salle Ventadour. In their repertoire, the ballet played a very small part, part, the costumes and sets were not remarkable, and the number of works was small; only a dozen new operas were staged between 1825 and 1870; but they included several famous works of Bel Canto opera, including I Puritani by Bellini and Marino Faliero and Don Pasquale by Donizetti. Verdi lived primarily in Paris between 1845 and 1847, and staged four of his operas at the Théâtre-Italien; Nabucco, Ernani, I due Foscari, and Jérusalem. The leading Italian singers also came regularly to sing at the Théâtre-Italien, including Giovanni Rubini, the creator of the role of Arturo in Bellini's I Puritani, Giulia Grisi, Fanny Persiani, Henriette Sontag and Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in Bellini's opera. [49]

French composers including Hector Berlioz struggled in vain against the tide of Italian operas. Berlioz succeeded in getting his opera Benvenuto Cellini staged at the Royal Academy in 1838, but it closed after just three performances, and was not staged again in France during his lifetime. Berlioz complained in the Journal des Debats that there were six operas by Donizetti in Paris playing in one year. "Monsieur Donizetti has the air to treat us like a conquered country," he wrote, "it is a veritable war of invasion. We can no longer call them the lyric theaters of Paris, just the lyric theaters of Monsieur Donizetti." [50]

The Conservatory and the symphony orchestra

With the growing popularity of classical music and the arrival of so many talented musicians, Paris encountered a shortage of concert halls. The best hall in the city was that of the Paris Conservatory on rue Bergére, which had excellent acoustics and could seat a thousand persons. Berlioz premiered his Symphonie Fantastique there on December 30, 1830; on December 29, 1832, Berlioz presented the Symphony again, along with two new pieces, Lelio and Harold en Italie, which he wrote specially for Paganini to play. At the end of the performance, with Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas in the audience, Paganini bowed down humbly before Berlioz. in tribute.

The Concert Society of the Paris Conservatory was founded in 1828, especially to play the symphonies of Beethoven; one at each performance, along with works by Mozart, Hayden and Handel. It was the first professional symphonic association in Europe. A second symphony association, the Societé de Sainte-Cecile, was founded shortly afterwards, which played more modern music; it presented the Paris premieres of Wagner's Tannhauser overture, works by Schubert, the Symphonie Italienne of Mendelssohn, the Fuite en Égypte of Berlioz, and the first works of Charles Gounod and Georges Bizet.[51]

Birth of the romantic ballet

The ballet had been an integral part of the Paris Opera since the time of Louis XIV the 17th century. A new style, Romantic ballet, was born on March 12, 1832 with the premiere of La Sylphide at the Salle Le Peletier, with choreography by Filippo Taglioni and music by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer.[52] Taglioni designed the work as a showcase for his daughter Marie. La Sylphide was the first ballet where dancing en pointe had an aesthetic rationale and was not merely an acrobatic stunt. Other romantic ballets that had their first performances at the Opera were Giselle (1841), Paquita' (1846) and Le corsaire (1856) Among the great ballerinas to grace the stage of the Opéra during this time were Marie Taglioni, Carlotta Grisi, Carolina Rosati, Fanny Elssler, Lucile Grahn, and Fanny Cerrito.

Lucien Petipa danced the male lead in Giselle at its premiere, and his younger brother Marius Petipa also danced for a time at the Paris Opera. Marius Petipa moved from Paris to Saint Petersburg, where he became the ballet-master for the Russian Imperial ballet and created many celebrated ballets, including The Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère and The Nutcracker.

Balls, Concerts-Promenades and the Romance

The Champs-Élysées was redeveloped in the 1830s with public gardens at either end, and became a popular place for Parisians to promenade. It was soon lined with restaurants, cafes-chantants. and pleasure gardens where outdoor concerts and balls were held. The Café Turc opened a garden with a series of concert-promenades in in the spring of 1833, which alternated symphonic music with quadrilles and airs for dancing. The 17-year-old jacques Offenbach wrote his first compositions for the dance orchestra at the Café Turc. The Tivoli, the Bazar of rue Saint-Honoré and the Casino Paganini competed with the Café Turc. In 1837, the King of the Viennese waltz, Johann Strauss, came in person to in Paris, competing with the French waltz king, Philippe Mustard. The outdoor concerts and balls did not stay in fashion for long; most of the gardens began to close after 1838. and Musard took charge instead of the famous masked balls at the Paris Opera. The Romance, a song with a simple, tender melody, sentimental words, accompanied on he piano, became the fashion in the Paris salons. Thousands of copies were sold by Paris publishers. [53]

The piano and the saxophone

The July monarchy saw a surge of sales nstruments, especially pianos, for the French upper and middle class. Production of pianos in Paris tripled between 1830 and 1847, from four thousand to eleven thousand a year. The companies organized concerts and sponsored famous musicians to promote their brands. Chopin was contracted to play exclusively the Pleyel piano, while Liszt played on the Érard piano. The Paris firms of Pleyel, Érard, Herz, Pape and Kriegelstein exported pianos around the world. The crafts of other instruments also flourished; the Parisian firm of Cavaillé-Coll reconstructed the great organs of Notre-Dame, Saint-Sulpice, an the Basilica of Saint-Denis, which had been destroyed during the French Revolution.

in 1842 the Belgian Adolphe Sax, 28-years old, arrived in Paris with his new invention, the saxophone. He won a silver medal for his new instrument at the Paris Exposition of French Industry in 1844, and in April 1845 won a competition held by the French Army on the Champs-de-Mars, in which a fanfare was played on traditional instruments and then on the instruments of of Adolphe Sax. The jury chose the instrument of Sax, and it was adapted by the French Army, and then by orchestras and ensembles throughout the world.

Popular music- street musicians and goguettes

At the beginning of the 1830s, the Paris police counted 271 wandering street musicians, 220 saltimbanques, 106 players of the barbary organ, and 135 itinerant street singers. The goguettes , or working class singing-clubs, continued to grow in the popularity, meeting in the back rooms of cabarets. The repertoire of popular songs ranged from romantic to comic and satirical, to political and revolutionary, especially in the 1840s. in June, 1848, the musical clubs were banned from meeting, as the government tried, without success, to stop the political unrest, which finally exploded into the 1848 French Revolution.

The 1848 Revolution and the the Second Republic

following the 1848 Revolution and the abdication of Louis-Philippe, the censorship of Paris theaters was briefly abolished. The Opera was renamed the Théâtre de la Nation, then Opéra-Théâtre de la Nation, then Académie nationale de musique. A new musical theater, the Théâtre-Lyrique, was created, devoted to presenting the works of young French composers, who had been largely ignored during the July monarchy. It was located on the Boulevard du Temple, the new theater district, in a building which had previously been occupied by the theater founded by Alexander Dumas to present historical plays.

The cafés chantants became increasingly popular, spreading from the Champs Élysées to the Grand boulevards. Some, like the Café des Ambassadeurs, had outdoor concert gardens lit by gaslights. They presented romances by popular singers, and also a new comic genre, the minstrel show, featuring French singers with blackened faces playing the banjo and violin. The famous music cafés included the Moka on rue de la Lune, the Folies and Eldorado on boulevard Strasbourg, and the Alcazar on rue de Faubourg-Poissonniére,[54]

The Second Empire

The Imperial Opera - Verdi and Wagner

During the reign of Emperor Napoleon III (1852-1870), the top of the hierarchy of Paris theaters was the Académie Imperial, or Imperial Opera Theatre, in the Salle Peletier. The opera house on Rue le Peletier could seat 1800 spectators. There were three performances a week, scheduled so as not to compete with the other major opera house in the city, Les Italiens. The best seats were in the forty boxes, which could each hold four or six persons, on the first balcony. One of the boxes could be rented for the entire season for 7500 francs. One of the major functions of the opera house was to be a meeting place for Paris society, and for this reason the performances were generally very long, with as many as five intermissions. Ballets were generally added in the middle of operas, to create additional opportunities for intermissions. The Salle Peletier had one infamous moment in its history; on 14 January 1858, a group of Italian extreme nationalists attempted to kill Napoleon III at the entrance of the opera house; they set off several bombs, which killed eight people and injured one hundred and fifty persons, and splattered the Empress Eugénie de Montijo with blood, though the Emperor was unharmed.[55]

Giuseppe Verdi played an important part in the glory of the Paris opera. He had first performed Nabucco in Paris in 1845 at the Théâtre-Italien, followed by Luisa Miller and Il trovatore He signed a new contract with the Paris Opera in 1852, and wanted absolute perfection for his next Parisian project, Les Vêpres siciliennes He complained that the Paris orchestra and chorus were unruly and undisciplined, and rehearsed them an unheard-of one hundred an sixty-one times before he felt they were ready. His work was rewarded; the opera was a critical and popular success, performed 150 times, rather than the originally proposed forty performances. He was unhappy, however, that his operas were less successful in Paris than those of his chief rival, Meyerbeer; he returned to Italy and did not come back for several years. He was persuaded to return to stage Don Carlos, commissioned especially for the Paris Opera. Once again he ran into troubles; one singer took him to court over the casting, and rivalries between other singers poisoned the production. He wrote afterwards, "I am not a composer for Paris I believe in inspiration; others only care about how the pieces are put together".[56]

Napoleon III intervened personally to have Richard Wagner come back to Paris; Wagner rehearsed the orchestra sixty-three times for the first French production of Tannhäuser on March 13, 1861. Unfortunately, Wagner was unpopular with both the French critics and with the the members of the Jockey Club, an influential French social society. During the premiere, with Wagner in the audience, the Jockey Club members whistled and jeered from the first notes of the Overture. After just three performances, the Opera was pulled from the repertoire. Wagner got his revenge in 1870, when the Prussian Army captured Napoleon III and surrounded Paris; he wrote a special piece of music to celebrate the event, Ode to the German Army at Paris." [55]

Napoleon III wanted a new opera house to be the centerpiece connecting the new boulevards he was constructing on the right bank. The competition was won by Charles Garnier and the first stone was laid by the Emperor in July 1862, but flooding of the basement caused the construction to proceed very slowly. As the building rose, it was covered with a large shed so the sculptors and artists could create the elaborate exterior decoration. The shed was taken off on August 15, 1867, in time for the Paris Universal Exposition, so visitors and Parisians could see the glorious new building; but the inside was not finished until 1875, after Napoleon's fall.

Hervé, Offenbach and the Opéra Bouffes

The operetta was born in Paris with the work of Louis Auguste Florimond Ronger, better known under the name of Hervé. His first operetta was called Don Quilchotte et Sancho Panza, performed in 1848 at the théâtre Montmartre. In the beginning they were short comic works or parodies, with a combination of songs, dance and dialogue, rarely with more than two persons on stage, and rarely longer than one act. Early operettas by Hervé was named Latrouillat and Truffaldini or the Inconvenience of a vendetta infinitely too prolonged and Agammemnon or the Camel with Two humps. Hervé opened a new theater, the Folies-Concertantes, on the Boulevard du Temple in 1854, later renamed the Folies-Nouvelle. The new genre was termed Opera Bouffe; works by Hervé appeared at a half-dozen theaters in the city, though the genre was ignored by the opera and the other official theaters.

In 1853, the young German-born musician and composer Jacques Offenbach, then director of the orchestra of the Comedie-Française, wrote his firs operetta in the new style, Pepita for the Théatre des Varietes. It was a success, but Offenbach was still unable to perform his works in the official theaters. During the first Paris Universal Exposition, he opened his own theater, the Bouffes-Parisiens, in an old theater at the Carré Marigny on the Champs-Élysées. It was an immense success; Rossini termed Offenbach "The Mozart of the Champs-Elysees". Offenbach moved to a larger theatre on the passage Choiseul, and presented his next operetta, Ba-ta-clan, which also enjoyed spectacular success. In 1858 Offenbach wrote a more serious and ambitious work, Orphée aux enfers, a four-act opera with a large cast and chorus. It was also a popular and critical success; Emperor Napoleon III attended, and afterwards presented Offenbach with French citizenship. With the approval of the Emperor, the official theaters of Paris were finally open to Offenbach, and his works became popular with the upper classes. He achieved further success with La Belle Hélène with Hortense Schneider in the leading role; then, again with Schneider, in La Vie parisienne ad la Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein In 1867, five different Paris theaters were staging works by Offenbach. He was the champion of the Paris operetta, but he also had the ambition to be considered a serious composer of orchestral works; ,unfortunately he died before the successful premiere of his most ambitious orchestral work, the Contes d'Hoffmann. [57]

The Théâtre Italien, the Théâtre-Lyrique, and the Opera-Comique

-

_during_'Don_Quichotte'_1869_-_NGO_3p872.jpg)

The Théâtre Lyrique, on Place Chatelet, in 1869. It hosted the first performances of the opera Faust and Romeo et Juliette by Charles Gounod, and of The Pearl Fishers by Georges Bizet.

-

The Théâtre Lyrique was known for its lavish sets and staging. The throne room of Didon for the opera Les Troyens by Berlioz. a Carthage (1863)

-

The Salle Ventadour was the home of the Théâtre-Italien; The first French performances of the operas of Verdi were staged there, and the famed soprano Adelina Patti sang there regularly during the Second Empire.

Besides the Imperial Opera Theater, Paris had three other important opera houses; the Théâtre Italien, the Opera-Comique, and the Théâtre Lyrique.

The Théâtre Italien was the based atthe Salle Ventadour, and hosted the French premieres of several by Giuseppe Verdi, including Il Trovatore, La Traviata (1856), Rigoletto (1857) and Un ballo in maschera (1861). Verdi conducted his Requiem there, and Richard Wagner conducted a concert of selections from his operas. The soprano Adelina Patti had an exclusive contract to sing with the Italiens when she was in Paris.

The Théâtre Lyrique was originally located on the Rue de Temple, the famous "Boulevard de Crime," but when that part of the street was demolished to make room for the Place de la Republique, Napoleon III built a new theater for them at Place du Châtelet. The Lyrique was famous for putting on operas by new composers; it staged the first French performance of Rienzi by Richard Wagner; the first performance of Les pêcheurs de perles (1863), the first opera by the 24-year-old Georges Bizet; the first performances of the operas Faust (1859) and Roméo et Juliette (1867) by Charles Gounod; and the first performance of Les Troyens (1863) by Hector Berlioz.

The Opéra-Comique was located in the Salle Favart, and staged both comedies and serious works. It staged the first performances of Mignon by Ambroise Thomas (1866) and of La grand'tante, the first opera of Jules Massenet (1867).

Romantic Ballet

Paris also had an enormous influence on the development of romantic ballet, thanks to the ballet troupe of the Paris Opera and its famous ballet masters. The first performance of Le Corsaire, choreographed by the ballet master of the opera, Joseph Mazilier to the music of Adolphe Adam, took place at the Paris Opera on on January 23, 1856. Coppélia was originally choreographed by Arthur Saint-Léon to the music of Léo Delibes, and was based upon two stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann: It premiered on 25 May 1870 at the Théâtre Impérial l'Opéra, with the 16-year-old Giuseppina Bozzacchi in the principal role of Swanhilde. Its first flush of success was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Paris (which also led to the early death of Giuseppina Bozzacchi, on her 17th birthday), but eventually it became the most-performed ballet at the Opéra.

The Cirque-Napoleon, concerts in the parks, and the Paris Expositions

Napoleon III re-established the custom of concerts at the imperial court, performed at the Louvre, with a new orchestra composed of students at the Paris Conservatory under the direction of Jules Pasdeloup. To reach a broader public, in 1861 he began a series of concerts by the orchestra at the huge Cirque-Napoléon (now the Cirque d'hiver) which could four thousand persons. Admission was fifty centimes. 1861 Pasdeloup decided to widen the audience for his orchestra. Besides playing the classical works of Beethoven, Mozart, Hayden and Mendellsohn, the orchestra performed new works by Schumann, Wagner, Berlioz, Gounod, and Saint-Saëns.