Yerevan

| Yerevan Երևան | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

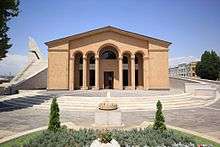

From top left: Yerevan skyline with Mount Ararat • Karen Demirchyan Complex Tsitsernakaberd Genocide Memorial • Saint Gregory Cathedral Tamanyan Street and the Yerevan Opera • Cafesjian Museum at the Cascade Republic Square | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): "The Pink City"[1][2] (վարդագույն քաղաք[3] vardaguyn k'aghak' , literally "rosy city")[4] | |||

Location within Armenia | |||

| Coordinates: 40°11′N 44°31′E / 40.183°N 44.517°ECoordinates: 40°11′N 44°31′E / 40.183°N 44.517°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Founded as Erebuni by Argishti I | 782 B.C. | ||

| City status by Alexander II of Russia | 1 October 1879[5] | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor–Council | ||

| • Body | City Council | ||

| • Mayor | Taron Margaryan (Republican) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 223 km2 (86 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 989.4 m (3,246.1 ft) | ||

| Population (2011)[6] | |||

| • Total | 1,060,138 | ||

| • Density | 4,800/km2 (12,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Yerevantsi(s)[7][8] | ||

| Time zone | GMT+4 (UTC+4) | ||

| Area code(s) | +374 10 | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Yerevan (/ˌjɛrəˈvɑːn/; (Eastern Armenian: Երևան; Western Armenian: Երեւան) [jɛɾɛˈvɑn], ![]() listen ),[lower-alpha 1] is the capital and largest city of Armenia, and one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities.[11] Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and industrial center of the country. It has been the capital since 1918, the thirteenth in the history of Armenia, and the seventh located in or around the Ararat plain.

listen ),[lower-alpha 1] is the capital and largest city of Armenia, and one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities.[11] Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and industrial center of the country. It has been the capital since 1918, the thirteenth in the history of Armenia, and the seventh located in or around the Ararat plain.

The history of Yerevan dates back to the 8th century BC, with the founding of the fortress of Erebuni in 782 BC by king Argishti I at the western extreme of the Ararat plain.[12] Erebuni was "designed as a great administrative and religious centre, a fully royal capital."[13] During the centuries long Iranian rule over Eastern Armenia that lasted from the early 16th century up to 1828, it was the center of Iran's Erivan khanate administrative division from 1736. In 1828, it became part of Imperial Russia alongside the rest of Eastern Armenia which conquered it from Iran through the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828). After World War I, Yerevan became the capital of the First Republic of Armenia as thousands of survivors of the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire settled in the area.[14] The city expanded rapidly during the 20th century as Armenia became part of the Soviet Union. In a few decades, Yerevan was transformed from a provincial town within the Russian Empire, to Armenia's principal cultural, artistic, and industrial center, as well as becoming the seat of national government.

With the growth of the economy of the country, Yerevan has been undergoing major transformation as many parts of the city have been the recipient of new construction since the early 2000s, and retail outlets as much as restaurants, shops, and street cafes, which were rare during Soviet times, have multiplied.

As of 2011, the population of Yerevan was 1,060,138, making up to 35.1% of the total population of Armenia.

Yerevan was named the 2012 World Book Capital by UNESCO.[15] Yerevan is an associate member of Eurocities.[16]

Etymology

One theory regarding the origin of Yerevan's name is the city was named after the Armenian king, Yervand (Orontes) IV, the last leader of the Orontid Dynasty, and founder of the city of Yervandashat.[17] However, it is likely that the city's name is derived from the Urartian military fortress of Erebuni (Էրեբունի), which was founded on the territory of modern-day Yerevan in 782 BC by Argishti I.[17] As elements of the Urartian language blended with that of the Armenian one, the name eventually evolved into Yerevan (Erebuni = Erevani = Erevan = Yerevan). Scholar Margarit Israelyan notes these changes when comparing inscriptions found on two cuneiform tablets at Erebuni:

The transcription of the second cuneiform bu [original emphasis] of the word was very essential in our interpretation as it is the Urartaean b that has been shifted to the Armenian v (b > v). The original writing of the inscription read «er-bu-ni»; therefore the prominent Armenianologist-orientalist Prof. G. A. Ghapantsian justly objected, remarking that the Urartu b changed to v at the beginning of the word (Biani > Van) or between two vowels (ebani > avan, Zabaha > Javakhk)....In other words b was placed between two vowels. The true pronunciation of the fortress-city was apparently Erebuny.[18]

Early Christian Armenian chroniclers attributed the origin of the name, "Yerevan," to a derivation from an expression exclaimed by Noah, in Armenian. While looking in the direction of Yerevan, after the ark had landed on Mount Ararat and the flood waters had receded, Noah is believed to have exclaimed, "Yerevats!" ("it appeared!").[17]

In the late medieval and early modern periods, when Yerevan was under Turkic and later Persian rule the city was known in Farsi as Iravân (Persian: ایروان). This term is still widely used by Azerbaijanis (Azerbaijani: İrəvan). The city was officially known as Erivan (Russian: Эривань) under Russian rule during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The city was renamed to Yerevan (Ереван) in 1936.[19] Up until the mid-1970s the city's name was spelled Erevan, more often than Yerevan, in English sources.[20]

Symbols

The principal symbol of Yerevan is Mount Ararat, which is visible from any area in the capital. The seal of the city is a crowned lion on a pedestal with the inscription "Yerevan." The lion's head is turned backwards while it holds a scepter using the right front leg, the attribute of power and royalty. The symbol of eternity is on the breast of the lion with a picture of Ararat in the upper part. The emblem is a rectangular shield with a blue border.[23]

On 27 September 2004, Yerevan adopted an anthem, "Erebuni-Yerevan", written by Paruyr Sevak and composed by Edgar Hovhanisyan. It was selected in a competition for a new anthem and new flag that would best represent the city. The chosen flag has a white background with the city's seal in the middle, surrounded by twelve small red triangles that symbolize the twelve historic capitals of Armenia. The flag includes the three colours of the Armenian National flag. The lion is portrayed on the orange background with blue edging.[24]

History

The territory of Yerevan was settled approximately during the 4th millennium BC, fortified settlements from the Bronze Age include Shengavit, Tsitsernakaberd, Teishebaini, Arin Berd and Berdadzor.

Erebuni and Urartu period

The ancient kingdom of Urartu was formed in the 9th century BC in the basin of Lake Van of the Armenian Highland, including the territory of modern-day Yerevan. King Arame was the founder of the kingdom, that was one of the most developed states of its age.[25] Archaeological evidence, such as a cuneiform inscription,[26] indicates that the Urartian military fortress of Erebuni (Էրեբունի) was founded in 782 BC by the orders of King Argishti I at the site of modern-day Yerevan, to serve as a fort and citadel guarding against attacks from the north Caucasus.[17] Yerevan, as mentioned, is considered one of the oldest cities in the world.[27] The cuneiform inscription found at Erebuni Fortress reads:

By the greatness of the God Khaldi, Argishti, son of Menua, built this mighty stronghold and proclaimed it Erebuni for the glory of Biainili [Urartu] and to instill fear among the king's enemies. Argishti says, "The land was a desert, before the great works I accomplished upon it. By the greatness of Khaldi, Argishti, son of Menua, is a mighty king, king of Biainili, and ruler of Tushpa." [Van].[28]

During the height of the Urartian power, irrigation canals and an artificial reservoirs were built in Erebuni and its surrounding territories. In 585 BC, the fortress of Teishebaini (Karmir Blur) located around 45 km north of Yerevan, was destroyed by an alliance of Medes and the Scythians.

Median and Achaemenid rules

In 590 BC, following the fall of the Kingdom of Urartu in the hands of the Iranian Medes, Erebuni along with the Armenian Highland became part of the Median Empire.

However, in 550 BC, the Median Empire was conquered by Cyrus the Great, and Erebuni became part of the Achaemenid Empire. Between 522 BC and 331 BC, Erebuni was one of the main centers of the Satrapy of Armenia, a region controlled by the Orontid Dynasty as one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire. The Satrapy of Armenia was divided into two parts: the northern part and the southern part, with the cities of Erebuni (Yerevan) and Tushpa (Van) as their centres, respectively.

Coins issued in 478 BC along with many other items found in the Erebuni Fortress, reveal the importance of Erebuni as a major centre for trade under the Achaemenid rule.

After 2 centuries under the Achaemenid rule, Erebuni has gradually turned into city of Persian image, culture and heritage.

Ancient Kingdom of Armenia

During the victorious period of Alexander the Great, and following the decline of the Achaemenid Empire, the Orontid rulers of the Armenian Satrapy achieved independence as a result of the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC, founding the Kingdom of Armenia. With the establishment of new cities such as Armavir, Zarehavan, Bagaran and Yervandashat, the importance of Erebuni had gradually declined.

With the rise of the Artaxiad dynasty of Armenia who seized power in 189 BC, the Kingdom of Armenia greatly expanded to include major territories of Asia Minor, Atropatene, Iberia, Phoenicia and Syria. The Artaxiads considered Erebuni and Tushpa as cities of Persian heritage. Consequently, new cities and commercial centres were built by Kings Artaxias I, Artavasdes I and Tigranes the Great. Thus, with the dominance of cities such as Artaxata and Tigranocerta, Erebuni had significantly lost its importance as a central city.

Under the rule of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia (54-428 AD), many other cities around Erebuni including Vagharshapat and Dvin flourished. Consequently, Erebuni was completely neutralized, losing its role as an economic and strategic centre of Armenia. During the period of the Arsacid kings, Erebuni was only recorded in a Manichaean text of the 3rd century, where it is mentioned that one of the disciples of the prophet Mani founded a Manichaean community near the Christian community in Erebuni.

According to Ashkharatsuyts, Erebuni was part of the Kotayk canton (Կոտայք գավառ, Kotayk gavar, not to be confused with the current Kotayk Province) of Ayrarat province, within Armenia Major.

Armenia became a Christian nation in the early 4th century, during the reign of the Arsacid king Tiridates III. The 5th-century church of Saint Paul and Peter was among the earliest churches ever built in Erebuni (demolished in November 1930 by the anti-religious Soviet authorities).

Sasanian period

Following the partition of Armenia by the Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Persia in 387 and in 428, Erebuni and the entire territory of Eastern Armenian came under the rule of Sasanid Persia.[29] The Armenian territories formed the province of Persian Armenia within the Sasanian Empire.

Due to the diminished role of Erebuni, as well as the absence of proper historical data, much of the city's history under the Sasanian rule is unknown.

The Katoghike Tsiranavor Church of Avan built between 595 and 602 during the Sasanian rule, is the city's oldest surviving church (partly damaged during the 1679 earthquake).

The province of Persian Armenia (also known as Persarmenia) lasted until 646, when the province was dissolved with the Muslim conquest of Persia.

Arab Islamic invasion

In 658 AD, at the height of the Arab Islamic invasions, Erebuni-Yerevan was conquered during the Muslim conquest of Persia, as it was part of Persian-ruled Armenia. The city became part of the Emirate of Armenia under the Umayyad Caliphate. The city of Dvin was the centre of the newly created emirate. Starting from this period, as a result of the developing trade activities with the Arabs, the Armenian territories had gained strategic importance as a crossroads for the Arab caravan routes passing between Europe and India through the Arab-controlled Ararat plain of Armenia. Most probably, "Erebuni" has become to be known as "Yerevan" since at least the 7th century AD.

Bagratid Armenia

After 2 centuries of Islamic rule over Armenia, the Bagratid prince Ashot I of Armenia led the revolution against the Abbasid Caliphate. Ashot I liberated Yerevan in 850, and was recognized as the Prince of Princes of Armenia by the Abbasid Caliph al-Musta'in in 862. Ashot was later crowned King of Armenia through the consent of Caliph al-Mu'tamid in 885. During the rule of the Bagratuni dynasty of Armenia between 885 and 1045, Yerevan was relatively a secure part of the Kingdom before being falling to the Byzantines.

However, Yerevan did not have any strategic role during the reign of the Bagratids, who developed many other cities of Ayrarat, such as Shirakavan, Dvin, and Ani.

Seljuk period, Zakarid Armenia and Mongol rule

After a brief Byzantine rule over Armenia between 1045 and 1064, the invading Seljuks -led by Tughril and later by his successor Alp Arslan- ruled over the entire region, including Yerevan. However, with the establishment of the Zakarid Principality of Armenia in 1201 under the Georgian protectorate, the Armenian territories of Yerevan and Lori had significantly grown. After the Mongols captured Ani in 1236, Armenia turned into a Mongol protectorate as part of the Ilkhanate, and the Zakarids became vassals to the Mongols. After the fall of the Ilkhanate in the mid-14th century, the Zakarid princes ruled over Lori, Shirak and Ararat plain until 1360 when they fell to the invading Turkic tribes.

Ag Qoyunlu and Kara Koyunlu tribes

During the last quarter of the 14th century, the Ag Qoyunlu Sunni Oghuz Turkic tribe took over Armenia, including Yerevan. In 1400, Timur invaded Armenia and Georgia, and captured more than 60,000 of the survived local people as slaves. Many districts including Yerevan were depopulated.[30]

In 1410, Armenia fell under the control of the Kara Koyunlu Shia Oghuz Turkic tribe. According to the Armeian historian Thomas of Metsoph, although the Kara Koyunlu levied heavy taxes against the Armenians, the early years of their rule were relatively peaceful and some reconstruction of towns took place.[31] The Kara Koyunlus have made Yerevan the centre of the newly formed Chukhur Saad administrative territory. The territory was named after a Turkic leader known as Emir Saad.

However, this peaceful period was shattered with the rise of Qara Iskander between 1420 and 1436, who reportedly made Armenia a "desert" and subjected it to "devastation and plunder, to slaughter, and captivity".[32] The wars of Iskander and his eventual defeat against the Timurids, invited further destruction in Armenia, as many more Armenians were taken captive and sold into slavery and the land was subjected to outright pillaging, forcing many of them to leave the region.[33]

Following the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in 1375, the seat of the Armenian Church was transferred from Sis back to Vagharshapat near Yerevan in 1441. Thus, Yerevan became the main economic, cultural and administrative centre in Armenia.

Iranian rule

In 1501, most of the Eastern Armenian territories including Yereven were swiftly conquered by the emerging Safavid dynasty of Iran led by Shah Ismail I.[34] Soon after in 1502, Yerevan became the centre of the Erivan Beglarbegi, a new administrative territory of Iran formed by the Safavids. For the following 3 centuries, it remained, with brief intermissions, under the Iranian rule. Due to its strategic significance, Yerevan was initially often fought over, and passed back and forth, between the dominion of the rivaling Iranian and Ottoman Empire, until it permanently became controlled by the Safavids. In 1555, Iran had secured its legitimate possession over Yerevan with the Ottomans through the Treaty of Amasya.[35]

In 1582-1583, the Ottomans led by Serdar Ferhad Pasha took brief control over Yerevan. Ferhad Pasha managed to build the Erivan Fortress on the ruins of one thousand-years old ancient Armenian fortress, on the shores of Hrazdan river.[36] However, the Ottomans ruled over the city until 1604 when the Persians regained control over Yerevan as a result of first Ottoman-Safavid War at the beginning of the 17th century.

Shah Abbas I of Persia who ruled between 1588 and 1629, ordered the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Armenians including citizens from Yerevan to mainland Persia. As a consequence, Yerevan significantly lost its Armenian population who had declined to 20%, while Muslims including Persians, Turks, Kurds and Tatars gained dominance with around 80% of the city's population. Muslims were either sedentary, semi-sedentary, or nomadic. Armenians mainly occupied the Kond neighbourhood of Yerevan and the rural suburbs around the city. However, the Armenians dominated over various professions and trade in the area and were of great economic significance to the Persian administration.[37]

As a result of the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, the Iranians reconfirmed their control over Eastern Armenia, including Yerevan. On 7 June 1679, a devastating earthquake razed the city to the ground.

In 1724, the Erivan Fortress was besieged by the Ottoman army. After a period of resistance, the fortress fell to the Turks. As a result of the Ottoman invasion, the Erivan Beglarbegi of the Safavids was dissolved.

Following a brief period of Ottoman rule over Eastern Armenia between 1724 and 1736, and as a result of the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, Yerevan along with the adjacent territories became part of the newly formed administrative territory of Erivan Khanate under the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, which encompassed an area encompassing 15,000 km².[38] The Afsharids controlled Eastern Armenia from the mid 1730s until the 1790s. Following the fall of the Afsharids, the Qajar dynasty of Iran took control of Eastern Armenia until 1828, when the region was conquered by the Russian Empire after their victory over the Qajars that resulted in the Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828. This was the 2nd major territorial loss for the Qajars, after the irrevocable loss of what is modern-day Georgia, Dagestan, and most of the contemporary Republic of Azerbaijan in favour of Russia as a result of the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813.[39]

Russian rule

.jpg)

During the second Russo-Persian War of the 19th century, the Russo-Persian War of 1826–28, Yerevan was captured by Russian troops under general Ivan Paskevich on 1 October 1827.[17][40][41] It was formally ceded by the Iranians in 1828, following the Treaty of Turkmenchay.[42] After 3 centuries of Iranian occupation, Yereven along with the rest of Eastern Armenia designated as the "Armenian Oblast", became part of the Russian Empire, a period that would last until to collapse of the Empire in 1917. The Russians sponsored the resettlement process of the Armenian population from Persia and Turkey. Due to the resettlement, the percentage of the Armenian population of Yerevan increased from 28% to 53.8%. The resettlement was intended to create Russian power bridgehead in the Middle East.[43] In 1829, Armenian repatriates from Persia were resettled in the city and a new quarter was built.

Yerevan served as the seat of the newly formed Armenian Oblast between 1828 and 1840. By the time of Nicholas I's visit in 1837, Yerevan had become an uyezd. In 1840, the Armenian Oblast was dissolved and its territory incorporated into a new larger province; the Georgia-Imeretia Governorate. In 1850 the territory of the former oblast was reorganized into the Erivan Governorate, covering an area of 28,000 km². Yerevan was the centre of the newly established governorate. At the period, Yerevan was a small town with narrow roads and allies, including the central quarter of Shahar, the Ghantar commercial centre, and the residential neighbourhoods of Kond, Dzoragyugh, Nork and Shentagh. The first major plan of the city was adopted in 1856, during which, Saint Hripsime and Saint Gayane women's colleges were founded and the English Park was opened. Zacharia Gevorkian opened Yerevan's first printing house in 1874, and the first theatre 1879. The Astafyan street was redeveloped and opened in 1863. During the 1840s and the 1850s, many schools were opened in the city. In 1881, The Yerevan Teachers' Seminary was opened. During the same year, the Yerevan Brewere was opened as well. In 1887, the Tairyan's wine and brandy factory was inaugurated. Other factories for alcoholic beverages and mineral water were opened during the 1890s. The monumental church of Saint Gregory the Illuminator was opened in 1900. Electricity and telephone lines were introduced to the city in 1907 and 1913 respectively.

In general, Yerevan had rapidly grown under the Russian rule, both economically and politically. Old buildings torn down and new buildings of European style erected instead.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Yerevan city's population was over 29,000.[44] In 1902, a railway line linked Yerevan with Alexandropol, Tiflis and Julfa. In the same year, Yerevan's first public library was opened. In 1905, the grandnephew of Napoleon I; prince Louis Joseph Jérôme Napoléon (1864–1932) was appointed as governor of Yerevan province.[45] In 1913, for the first time in the city, a telephone line with eighty subscribers became operational.

Yerevan served as the centre of the governorate until 1917, when Erivan governorate was dissolved with the collapse of the Russian Empire.

Brief independence

%2C_Yerevan.jpg)

At the beginning of the 20th century, Yerevan was a small city with a population of 30,000.[46] In 1917, the Russian Empire ended with the October Revolution. In the aftermath, Armenian, Georgian and Muslim leaders of Transcaucasia united to form the Transcaucasian Federation and proclaimed Transcaucasia's secession.

The Federation, however, was short-lived. After gaining control over Alexandropol (Gyumri), the Turkish army was advancing towards the south and east to eliminate the center of Armenian resistance based in Yerevan. On May 21, 1918, the Turks started their campaign moving towards Yerevan via Sardarabad. Catholicos Gevorg V ordered that church bells peal for 6 days as Armenians from all walks of life – peasants, poets, blacksmiths, and even the clergymen – rallied to form organized military units.[47] Civilians, including children, aided in the effort as well, as "Carts drawn by oxen, water buffalo, and cows jammed the roads bringing food, provisions, ammunition, and volunteers from the vicinity" of Yerevan.[48]

By the end of May 1918, Armenians were able to defeat the Turkish army in the battles of Sardarabad, Abaran and Karakilisa. Thus, on 28 May 1918, the Dashnak leader Aram Manukian declared the independence of Armenia. Subsequently, Yerevan became the capital and the center of the newly founded Republic of Armenia, although the members of the Armenian National Council were yet to stay in Tiflis until their arrival in Yerevan to form the government in the summer of the same year. Armenia became a parliamentary republic with four administrative divisions. The capital Yerevan was part of the Araratian Province. At the time, Yerevan received more than 75,000 refugees from Western Armenia, who escaped the massacres perpetrated by the Ottoman Turks during the Armenian Genocide.

On 26 May 1919, the government passed a law to open the Yerevan State University, which was located on the main Astafyan (now Abovyan) street of Yerevan.

After the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, Armenia was granted formal international recognition. The United States, as well as many South American countries, officially opened diplomatic channels with the government of independent Armenia. Yerevan had also opened representatives in Great Britain, Italy, Germany, Serbia, Greece, Iran and Japan.

However, after the short period of independence, Yerevan fell to the Bolsheviks, and Armenia was incorporated into the Soviet Union on 2 December 1920. Although nationalist forces managed to retake the city in February 1921 and successfully released all the imprisoned political and military figures, the city's nationalist elite were once again defeated by the Soviet forces on 2 April 1921.

Soviet era

.jpg)

The Red Soviet Army invaded Armenia on 29 November 1920 from the northeast. On 2 December 1920, Yerevan along with the other territories of the Republic of Armenia, became part of the Soviet Union, known as the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. However, the Armenian SSR formed the Transcaucasian SFSR (TSFSR) together with the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, between 1922 and 1936.

Under the Soviet rule, Yerevan became the first among the cities in the Soviet Union for which a general plan was developed. The "General Plan of Yerevan" developed by the academician Alexander Tamanian, was approved in 1924. It was initially designed for a population of 150,000. The city was quickly transformed into a modern industrial metropolis of over one million people. New educational, scientific and cultural institutions were founded as well.

Tamanian incorporated national traditions with contemporary urban construction. His design presented a radial-circular arrangement that overlaid the existing city and incorporated much of its existing street plan. As a result, many historic buildings were demolished, including churches, mosques, the Persian fortress, baths, bazaars and caravanserais. Many of the districts around central Yerevan were named after former Armenian communities that were destroyed by the Ottoman Turks during the Armenian Genocide. The districts of Arabkir, Malatia-Sebastia and Nork Marash, for example, were named after the towns Arabkir, Malatya, Sebastia, and Marash, respectively. After the end of World War II, German POWs were used to help in the construction of new buildings and structures, such as the Kievyan Bridge.

Within the years, the central Kentron district has become the most developed area in Yerevan, something that created a significant gap compared with other districts in the city. Most of the educational, cultural and scientific institutions were centred in the Kentron district.

In 1965, during the commemorations of the fiftieth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, Yerevan was the location of a demonstration, the first such demonstration in the Soviet Union, to demand recognition of the Genocide by the Soviet authorities.[49] In 1968, the city's 2,750th anniversary was commemorated.

Yerevan played a key role in the Armenian national democratic movement that emerged during the Gorbachev era of the 1980s. The reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika opened questions on issues such as the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, the environment, Russification, corruption, democracy, and eventually independence. At the beginning of 1988, nearly one million Yerevantsis engaged in demonstrations concerning these subjects, centered on the Theater Square (currently Freedom Square).[50]

Independence era

Following the dismantling of the USSR, Yerevan became the capital of the Republic of Armenia on 21 September 1991. Maintaining supplies of gas and electricity proved difficult; constant electricity was not restored until 1996 amidst the chaos of the badly instigated and planned transition to a market based economy.

Since 2000, central Yerevan has been transformed into a vast construction site, with cranes erected all over the Kentron district. Officially, the scores of multi-storied buildings are part of large-scale urban planning projects. Roughly $1.8 billion was spent on such construction in 2006, according to the national statistical service. Prices for downtown apartments have increased by about ten times during the first decade of the 21st century. Many new streets and avenues were opened, such as the Argishti street, Italy street, Saralanj Avenue, Monte Melkonian Avenue, and the Northern Avenue.

However, as a result of this construction booming, the majority of the historic buildings located on the central Aram Street, were either entirely destroyed or transformed into modern residential buildings through the construction of additional floors. Only few structures were preserved, mainly in the portion that extends from Abovyan Street to Mashtots Avenue.

Political demonstrations turned into a common scene in Yerevan. In 2008, unrest in the capital between the authorities and opposition demonstrators led by ex-President Levon Ter-Petrosyan occurred after the 2008 Armenian presidential election. The events resulted in ten deaths[51] and a subsequent 20-day state of emergency declared by President Robert Kocharyan.[52]

Geography

Topography and location

Yerevan has an average height of 990 m (3,248.03 ft), with a minimum of 865 m (2,837.93 ft) and a maximum of 1,390 m (4,560.37 ft) above sea level.[53] It is located on to the edge of the Hrazdan River, northeast of the Ararat plain (Ararat Valley), to the center-west of the country. The upper part of the city is surrounded with mountains on three sides while it descends to the banks of the river Hrazdan at the south. The Hrazdan divides Yerevan into two parts through a picturesque canyon.

Historically, the city is situated at the heart of the Armenian Highland, in Kotayk canton (Armenian: Կոտայք գավառ Kotayk gavar, not to be confused with the current Kotayk Province) of Ayrarat province, within Armenia Major.

As the capital of Armenia, Yerevan is not part of any marz ("province"). Instead, it is bordered with the following provinces: Kotayk from the north and the east, Ararat from the south and the south-west, Armavir from the west and Aragatsotn from the north-west.

Climate

Yerevan features a steppe climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk), with long, hot, dry summers and short, but cold and snowy winters. This is attributed to Yerevan being on a plain surrounded by mountains and to its distance from the sea and its effects. The summers are usually very hot with the temperature in August reaching up to 40 °C (104 °F), and winters generally carry snowfall and freezing temperatures with January often being as cold as −15 °C (5 °F) and lower. The amount of precipitation is small, amounting annually to about 318 millimetres (12.5 in). Yerevan experiences an average of 2,700 sunlight hours per year.[53] Temperature regime in Yerevan is close to the southern Midwest cities such as Kansas City, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska, though Yerevan is much drier.

| Climate data for Yerevan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

35.0 (95) |

34.2 (93.6) |

38.6 (101.5) |

41.6 (106.9) |

42.0 (107.6) |

40.0 (104) |

34.1 (93.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

20.0 (68) |

42.0 (107.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.4 (92.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

4.6 (40.3) |

18.9 (66) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

6.3 (43.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.1 (79) |

21.1 (70) |

13.8 (56.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

1.1 (34) |

−3.9 (25) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.6 (−17.7) |

−26 (−15) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 20 (0.79) |

21 (0.83) |

29 (1.14) |

51 (2.01) |

42 (1.65) |

22 (0.87) |

16 (0.63) |

9 (0.35) |

8 (0.31) |

32 (1.26) |

26 (1.02) |

20 (0.79) |

296 (11.65) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 78 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 7 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 22 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 74 | 62 | 59 | 58 | 51 | 47 | 47 | 51 | 64 | 73 | 79 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 93.0 | 108 | 162 | 177 | 242 | 297 | 343 | 332 | 278 | 212 | 138 | 92 | 2,474 |

| Source #1: Pogoda.ru.net [54] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[55] | |||||||||||||

Government and politics

Capital

Yerevan has been the capital of Armenia since the independence of the First Republic in 1918. Situated in the Ararat plain, the historic lands of Armenia, it served as the best logical choice for capital of the young republic at the time.

When Armenia became a republic of the Soviet Union, Yerevan remained as capital and accommodated all the political and diplomatic institutions in the republic. In 1991 with the independence of Armenia, Yerevan continued with its status as the political and cultural centre of the country, being home to all the national institutions: the Government house, the Parliament, ministries, the presidential palace, the constitutional court, judicial bodies and other public organisations.

Municipality

The Armenian Constitution, adopted on 5 July 1995, granted Yerevan the status of a marz (region).[56] Therefore, Yerevan functions similarly to the other regions of the country with a few specificities.[57] The administrative authority of Yerevan is thus represented by:

- the mayor, appointed by the President (who can remove him at any moment) upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister,[56] alongside a group of four deputy mayors heading eleven ministries (of which financial, transport, urban development etc.),[58]

- the Yerevan City Council, regrouping the Heads of community districts under the authority of the mayor,[59]

- twelve "community districts", with each having its own leader and their elected councils.[60] Yerevan has a principal city hall and twelve deputy mayors of districts.

The last modification to the Constitution on 27 November 2005 turned the city into a "community" (hamaynk); since, the Constitution declares that this community has to be led by a mayor, elected directly or indirectly, and that the city needs to be governed by a specific law.[61] This law is currently in preparation in the Armenian parliament that adopted its first draft in December 2007 and should do the same in the second draft in spring of 2008.[62] The project on the law envisions an indirect election of the mayor.[63]

In addition to the national police and road police, Yerevan has its own municipal police. All three bodies cooperate to maintain law in the city.

Administrative districts

Yerevan is divided into twelve "administrative districts" (վարչական շրջան, varčakan šrĵan)[64] each with an elected leader. The total area of the 12 districts of Yerevan is 223 square kilometres (86 square miles).[65]

| District | Armenian | Population (2011 census) | Area (km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ajapnyak | Աջափնյակ | 108,282 | 25 |

| Arabkir | Արաբկիր | 117,704 | 12 |

| Avan | Ավան | 53,231 | 8 |

| Davtashen | Դավթաշեն | 42,380 | 6 |

| Erebuni | Էրեբունի | 123,092 | 48 |

| Kanaker-Zeytun | Քանաքեր-Զեյթուն | 73,886 | 8 |

| Kentron | Կենտրոն | 125,453 | 14 |

| Malatia-Sebastia | Մալաթիա-Սեբաստիա | 132,900 | 26 |

| Nork-Marash | Նորք-Մարաշ | 12,049 | 4 |

| Nor Nork | Նոր Նորք | 126,065 | 14 |

| Nubarashen | Նուբարաշեն | 9,561 | 18 |

| Shengavit | Շենգավիթ | 135,535 | 40 |

Demographics

| Year | Armenians | Azerbaijanisa | Russians | Others | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1650[66] | absolute majority | — | — | — | — | ||||

| c. 1725[67] | absolute majority | — | — | — | ~20,000 | ||||

| 1830[68] | 3,937 | 34.3% | 7,331 | 63.9% | — | 195 | 1.7% | 11,463 | |

| 1873[69] | 5,959 | 49.9% | 5,805 | 48.6% | 150 | 1.3% | 24 | 0.2% | 11,938 |

| 1897[70] | 12,523 | 43.2% | 12,359 | 42.6% | 2,765 | 9.5% | 1,359 | 4.7% | 29,006 |

| 1926[71] | 59,838 | 89.2% | 5,216 | 7.8% | 1,401 | 2.1% | 666 | 1% | 67,121 |

| 1939[71] | 174,484 | 87.1% | 6,569 | 3.3% | 15,043 | 7.5% | 4,300 | 2.1% | 200,396 |

| 1959[71] | 473,742 | 93% | 3,413 | 0.7% | 22,572 | 4.4% | 9,613 | 1.9% | 509,340 |

| 1970[72] | 738,045 | 95.2% | 2,721 | 0.4% | 21,802 | 2.8% | 12,460 | 1.6% | 775,028 |

| 1979[71] | 974,126 | 95.8% | 2,341 | 0.2% | 26,141 | 2.6% | 14,681 | 1.4% | 1,017,289 |

| 1989[73][74] | 1,100,372 | 96.5% | 897 | 0.0% | 22,216 | 2.0% | 17,507 | 1.5% | 1,201,539 |

| 2001[75] | 1,088,389 | 98.63% | — | 6,684 | 0.61% | 8,415 | 0.76% | 1,103,488 | |

| 2011[76] | 1.048.940 | 98.94% | — | 4,940 | 0,47% | 6258 | 0,59% | 1,060,138 | |

| ^a Called Tatars prior to 1918 | |||||||||

Originally a small town, Yerevan became the capital of Armenia and a large city with over one million inhabitants. Until the fall of the Soviet Union, the majority of the population of Yerevan were Armenians with minorities of Russians, Kurds, Azerbaijanis and Iranians present as well. However, with the breakout of the Nagorno-Karabakh War from 1988 to 1994, the Azerbaijani minority diminished in the country in what was part of population exchanges between Armenia and Azerbaijan. A big part of the Russian minority also fled the country during the 1990s economic crisis in the country. Today, the population of Yerevan is overwhelmingly Armenian.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, due to economic crises, thousands fled Armenia, mostly to Russia, North America and Europe. The population of Yerevan fell from 1,250,000 in 1989[53] to 1,103,488 in 2001[77] and to 1,091,235 in 2003.[78] However, the population of Yerevan has been increasing since. In 2007, the capital had 1,107,800 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

Yerevan was inhabited first by Armenians and remained homogeneous until the 15th century.[66][67][79] The population of the Erivan Fortress, founded in the 1580s, was mainly composed of Muslim soldiers, estimated two to three thousand.[66] The city itself was mainly populated by Armenians. French traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who visited Yerevan possibly up to six times between 1631 and 1668, states that the city is exclusively populated by Armenians.[80] During the 1720's Ottoman–Persian War its absolute majority were Armenians.[67] The demographics of the region changed because of a series of wars between the Ottoman Empire, Iran and Russia. By the early 19th century, Yerevan had a Muslim majority.

Until the Sovietizaton of Armenia, Yerevan was a multicultural city, mainly with Armenian and Caucasian Tatar (nowadays Azerbaijanis) population. After the Armenian Genocide, many refugees from what Armenians call Western Armenia (nowadays Turkey, then Ottoman Empire) escaped to Eastern Armenia. In 1919, about 75,000 Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire arrived in Yerevan, mostly from the Vaspurakan region (city of Van and surroundings). A significant part of these refugees died of typhus and other diseases.[81]

From 1921 to 1936, about 42,000 ethnic Armenians from Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Greece, Syria, France, Bulgaria etc. came to Soviet Armenia, with most of them settling in Yerevan. The second wave of repatriation occurred from 1946 to 1948, when about 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Cyprus, Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, France, United States etc. came to Soviet Armenia, again most of whom settled in Yerevan. Thus, the ethnic makeup of Yerevan became more monoethnic during the first 3 decades in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s and the early 1990s, the remaining 2,000 Azeris left the city, because of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Religion

The Armenian Apostolic Christianity is the dominant religion in Armenia as well as Yerevan. The Armenian Church is represented in the city by the Araratian Patriarchal Diocese, with the Surp Sarkis Cathedral being the seat of the prelacy. Yerevan is home to the largest Armenian church in the world, the Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, opened in 2001 when the entire Armenian nation had celebrated the 1700th anniversary of the establishment of the Armenian Church and the adoption of Christianity as a state religion in Armenia.

The tiny community of the Orthodox Russians has its own Church of the Intercession of the Holy Mother of God, located in the Kanaker-Zeytun district of Yerevan. The church was built across the barracks of the Cossack troops which had been deployed in Yerevan since the Russian victory in the Russian-Persian war in 1828. The church was closed in the Soviet times to be used first as a warehouse and later as a regimental club. Divine services were resumed in it only in 1991. In 2004, the reconstructed church re-acquired a cupola and a belfry.[82] The consecration of the new Holy Cross Russian Orthodox church of Yerevan was conducted on 18 March 2010, by Patriarch Kirill I of Moscow. The church is being built on Admiral Isakov Avenue and is set to be completed by the end of 2013.

After the capture of Yerevan by Russians as result of the Russo-Persian War, the main mosque in the fortress, built by the invading Turks in 1582, was converted into an Orthodox church under the orders of the Russian commander, general Ivan Paskevich. The church was sanctified on 6 December 1827 and named the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Mother of God.[83] According to Ivan Chopin, there were eight mosques in Yerevan in the middle of the 19th century.[84][85] The 18th-century Blue Mosque of Yerevan was restored and reopened in the latter half of the 1990s funded by Iran,[86] to become the only active mosque throughout the Republic of Armenia. Nowadays, Islamic religious services are conducted within the Blue Mosque to serve the Shia Iranian visitors and tradesmen.

Few members of the Yezidi and Jewish communities of Armenia live in Yerevan. The city is home to the Jewish Council of Armenia. A variety of other minor religious communities are also present in the city.

Culture

Museums

Yerevan is home to a large number of museums, art galleries and libraries. The most prominent of these are the National Gallery of Armenia, the History Museum of Armenia, the Cafesjian Museum of Art, the Matenadaran library of ancient manuscripts, and the Armenian Genocide museum. Moreover, many private galleries are in operation, with many more opening every year, featuring rotating exhibitions and sales.

Constructed in 1921, the National Gallery of Armenia is Yerevan's principal museum. It is integrated with the History Museum of Armenia. In addition to having a permanent exposition of works of painters such as Aivazovsky, Kandinsky, Chagall, Théodore Rousseau, Monticelli or Eugène Boudin,[87] it usually hosts temporary expositions such as Yann Arthus-Bertrand in 2005 or the one organized on the occasion of the Year of Armenia in France in October 2006.[88] The Armenian Genocide museum is found at the foot of Tsitsernakaberd memorial and features numerous eyewitness accounts, texts and photographs from the time. It comprises a Memorial stone made of three parts, the latter of which is dedicated to the intellectual and political figures who, as the museum's site says, "raised their protest against the Genocide committed against the Armenians by the Turks. Among them there are Armin T. Wegner, Hedvig Büll, Henry Morgenthau, Franz Werfel, Johannes Lepsius, James Bryce, Anatole France, Giacomo Gorrini, Benedict XV, Fritjof Nansen, Fayez al-Huseini". This place of remembrance was created by Laurenti Barseghian, the Museum's director, and Pietro Kuciukian, the founder of the "Memory is the Future" Committee for the Righteous for the Armenians. This Memorial hosts the ashes or fistfuls of earth from the tombs of the Righteous and of those non-Armenians who witnessed the genocide and tried to help the Armenians. Here, people also celebrates living characters who stand out for their pro-memory engagement.

Next to the Hrazdan river, the Sergey Parajanov Museum that was completely renovated in 2002, has 250 works, documents and photos[89] of the Armenian filmmaker and painter. Yerevan has several other museums like the museum of the Middle-East and the Museum of Yerevan.[90]

Here is a list of Yerevan's most notable museums:

- Erebuni museum, founded in 1968 near the Erebuni fortress.

- History Museum of Armenia, opened in 1921, has a collection of more than 400,000 items and pieces of Armenian heritage.

- National Gallery of Armenia, exhibits more than 25,000 painting samples of Armenian, Russian and European artists.

- Matenadaran library, museum and institute of ancient manuscripts named after Mesrop Mashtots.

- Cafesjian Museum of Art, Gerard L. Cafesjian Museum and Art Centre of the Cascade complex, opened on 7 November 2009, showcases a massive collection glass artwork, particularly the works of the Czech artists Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. The front gardens showcase sculptures from Gerard Cafesjian's collection.

- Armenian Genocide museum-institute at the Tsitsernakaberd genocide memorial.

- House-Museum of Hovhannes Tumanyan, opened in 1953, home to many personal belongings of poet Hovhannes Tumanyan along with his personal library.

- House-Museum of Aram Khachaturian, opened in 1984, contains more than 18,000 valuable items.

- House-Museum of Martiros Saryan, contains many art works of painter Martiros Saryan.

- House-Museum of Khachatur Abovian, the home of writer Khachatur Abovian in Kanaker, turned into a bigraphical museum in 1939.

- Sergei Parajanov Museum, opened in 1991, exhibits the works of Sergei Parajanov and many other directors.

- Military Museum within the Mother Armenia complex at the Victory Park, dedicated to the World War II and Nagorno-Karabakh War.

- Charents Museum of Literature and Arts, is a biographical museum of poet Yeghishe Charents, located on Aram Street.

- ARF History Museum, commemorates the history of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and its notable members.

- Yerevan History Museum, founded in 1931, reopened in 2005 adjacent to the new complex of the Yerevan City Hall.

- Komitas Museum, founded as an art and biographical museum in 2015, located near the Komitas Pantheon.

Libraries

The National Library of Armenia located on Teryan Street of Yerevan, is the public library of the city and the entire republic. It was founded in 1832 and is operating in its current building since 1939. Another national library of Yerevan is the Khnko Aper Children's Library, founded in 1933. Other major public libraries include the Avetik Isahakyan Central Library founded in 1935, the Republican Library of Medical Sciences founded in 1939, the Library of Science and Technology founded in 1957, and the Musical Library founded in 1965. In addition, each administrative district of Yerevan has its own public library (usually more than one library).

The Matenadaran is a library-museum and a research centre, regrouping 17,000 ancient manuscripts and several bibles from the Middle Ages. Its archives hold a rich collection of valuable ancient Armenian, Ancient Greek, Aramaic, Assyrian, Hebrew, Latin, Middle and Modern Persian manuscripts. It is located on Mashtots Avenue at central Yerevan.

On 6 June 2010, Yerevan was named as the 2012 World Book Capital by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The Armenian capital was chosen for the quality and variety of the programme it presented to the selection committee, which met at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris on 2 July 2010.

The National Archives of Armenia founded in 1923, is a scientific research centre and depositary, with a collection of around 3.5 million units of valuable documents.

Art

The city is home to many movie theatres including the Moscow Cinema, Nairi Cinema, Hayastan Cinema, Cinema Star multiplex cinemas of the Dalma Garden Mall, and the KinoPark multiplex cinemas of Yerevan Mall. Since 2004, the Moscow Cinema hosts annual the Golden Apricot international film festival. Other cinemas with notable architectural value include the Hayrenik Cinema, and Rossiya Cinema.

The Yerevan Opera and Ballet Theatre consists of two concert halls: Aram Khatchaturian concert hall and the hall of the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Alexander Spendiarian. The Komitas Chamber Music House is the home of chamber music in Armenia.

Numerous cultutal centres and halls host multiple shows and performances, such as the modern Complex named after Karen Demirchyan. Other significant theatres include: Sundukyan State Academic Theatre, Paronyan Musical Comedy Theatre, Stanislavski Russian Theatre, Drama and Comedy Theatre named after Edgar Elbakyan, Hrachya Ghaplanyan Drama Theatre, Yerevan State Hamazgayin Theatre and Hovhannes Tumanyan Puppet Theatre.

The Cafesjian Center for the Arts is known for its regularly programmed events including the "Cafesjian Classical Music Series" at the first Wednesday of each month, and the "Music Cascade" series of jazz, pop and rock music live concerts performed every Friday and Saturday.

The Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art founded in 1992 in Yerevan, is a creativity centre helping to exchange experience between professional artists in an appropriate atmosphere.

Monuments

- Erebuni Fortress, also known as or Arin Berd', is the hill where the city of Yerevan was founded in 782 BC by King Argishti I.

- Katoghike Tsiranavor Church of Avan, built in 591, being the city's oldest surviving church.

- Red Bridge, a 17th-century bridge on the Hrazdan River, built in 1679 and reconstructed in 1830.

- Surp Zoravor Astvatsatsin Church, rebuilt in 1693-1694, one of the best preserved churches in Yerevan.

- Blue Mosque or "Gök Jami", built between 1764 and 1768, located on Mashtots Avenue, is currently the only operating mosque in Armenia.

- Saint Sarkis Cathedral, is the seat of Araratian Pontifical Diocese of the Armenian Church, rebuilt between 1835 and 1842.

- Yerevan Opera Theater or the Armenian National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre opened in 1933.

- Komitas Pantheon is a cemetery opened in 1936 where many famous Armenians are buried, known for its artistic tombstones.

- Moscow Cinema, opened in 1937 on the site of Saint Paul and Peter Church of the 5th century which was destroyed in 1931.

- Mother Armenia, opened in 1950 at the Victory park, commemorates the World War II and Karabakh Liberation war.

- Matenadaran named after Mesrop Mashtots, is a museum-institute of ancient manuscripts opened in 1959, one of the world's richest depositories of manuscripts.

- Monument of David of Sasun, erected in 1959, dedicated to the legendary Armenian hero David of Sasun.

- Swan Lake, located at the opera park since 1963, turns into an ice-skating arena in winters.

- Yerevan Lake, is an artificial lake formed between 1963 and 1966 with a surface of 0.65 km2 (0.25 sq mi).

- Tsitsernakaberd monument, commemorating the victims of the Armenian Genocide, opened in 1967.

- Yerevan Vernissage, a large open-air exhibition-market formed during the 1980s.

- Yerablur Pantheon, is a military cemetery where over 1,000 Armenian martyrs of Nagorno-Karabakh War are buried since 1990.

- Yerevan Cascade, a massive staircase with fountains ascending up from the Tamanyan Street, completed during the 2000s, home to the Cafesjian Museum of Art.

- Saint Gregory Cathedral, is the largest Armenian church in the world, opened in 2001 to commemorate the 1700th anniversary of Christianity in Armenia.

Transportation

Air

Yerevan is served by the Zvartnots International Airport, located 12 kilometres (7 miles) west of the city center. It is the primary airport of the country and the hub of Air Armenia, national air carrier company. Inaugurated in 1961 during the Soviet era, Zvartnots airport was renovated for the first time in 1985 and a second time in 2002 in order to adapt to international norms. It went through a facelift starting in 2004 with the construction of a new terminal. The first phase of the construction ended in September 2006 with the opening of the arrivals zone. A second section designated for departures was inaugurated in May 2007. The departure terminal is anticipated, October 2011 housing state of the art facilities and technology. This will make Yerevan Zvartnots International Airport, the largest, busiest and most modern airport in the entire Caucasus.[91] The entire project costs more than $100 million USD.

A second airport, Erebuni Airport, is located just south of the city. Since the independence, "Erebuni" is mainly used for military or private flights. The Armenian Air Force has equally installed its base there and there are several MiG-29s stationed on Erebuni's tarmac.

Bus and trolleybus

Yerevan has 46 bus lines[92] and 24 trolleybus lines.[93] The Yerevan trolleybus system has been operating since 1949. Old Soviet-era buses have been replaced with new modern ones. Outside the bus lines that cover the city, some buses at the start of the central road train station located in the Nor Kilikia neighborhood serve practically all the cities of Armenia as well as of others abroad, notably Tbilisi in Georgia or Tabriz in Iran.

A new route network has been developed in the city, according to which the number of minibuses will be reduced from the currently existing 2600 to 650 by the end of 2010.[94]

The tramway network that operated in Yerevan since 1906 was decommissioned in January 2004. Its use had a cost 2.4 times higher than the generated profits, which pushed the municipality to shutdown the network,[95] despite a last-ditch effort to save it towards the end of 2003. Since the closure, the rails have been dismantled and sold.

Underground

The Yerevan Metro named after Karen Demirchyan, (Armenian: Կարեն Դեմիրճյանի անվան Երեւանի մետրոպոլիտեն կայարան (Karyen Dyemirchhani anvan Yeryewani myetropolityen kaharan)) is a rapid transit system that serves the capital city since 1981. It has a single line of 13.4 km (8.3 mi) length with 10 active stations. The interiors of the stations resemble that of the former western Soviet nations, with chandeliers hanging from the corridors. The metro stations had most of their names changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Independence of the Republic of Armenia.

A northeastern extension of the line with two new stations is currently being developed. The construction of the first station (Ajapnyak) and of the one kilometer tunnel linking it to the rest of the network will cost 18 million USD.[96] The time of the end of the project has not yet been defined. Another long term project is the construction of two new lines, but these have been suspended due to lack of finance.

More than 60,000 people are being transported by the Yerevan metro on a daily basis.

Railway

Yerevan has a single central train station (several train stations of suburbs have not been used since 1990) that is connected to the metro via the Sasuntsi Davit station. The train station is made in Soviet-style architecture with its long point on the building roof, representing the symbols of communism: red star, hammer and sickle. Due to the Turkish and Azerbaijani blockades of Armenia, there is only one international train that passes by once every two days, with neighboring Georgia being its destination. For example, for a sum of 9 000 to 18 000 dram, it is possible to take the night train to the Georgian capital, Tbilisi.[97] This train then continues to its destination of Batumi, on the shores of the Black sea in the summer season.

The only railway that goes to Iran to the south passes by the closed border of Nakhichevan. For this reason, there are no trains that go south from Yerevan. A construction project on a new railway line connecting Armenia and Iran directly is currently being studied.

During the first decade of the 21st century, the South Caucasus Railway CJSC -which is the current operator of the railway system in Armenia- announced its readiness to put the Yerevan-Gyumri-Kars railway line in service in case the Armenian-Turkish protocols are ratified and the opening of the borders between the two countries is achieved.

There are several number of suburb trains to:

- Armavir (4), Gyumri (2);

- Yeraskh (1), Ararat (2);

- Hrazdan (2), Shorzha (1, on route only in summer).

Taxi

Armenia is among the top 10 safest countries where one can wander around and go home alone safely at night. Yerevan prides itself on having connections 24/7 as taxis are available at any time of the day or night.[98]

Economy

Industry

As of 2013, the share of Yerevan in the annual total industrial product of Armenia is 41%.[99] The industry of Yerevan is quite diversified including chemicals, primary metals and steel products, machinery, rubber products, plastics, rugs and carpets, textiles, clothing and footwear, jewellery, wood products and furniture, building materials and stone-processing, alcoholic beverages, mineral water, dairy product and processed food. Even though the economic crisis of the '90s ravaged the industry of the country, several factories remain always in service, notably in the petrochemical and the aluminium sectors.

Armenian beverages, especially the Armenian cognac and beer have a worldwide fame. Hence, Yerevan is home to many leading enterprises of Armenia and the Caucasus for the production of alcoholic beverages, such as the Yerevan Brandy Company, Yerevan Ararat Wine Factory, "Yerevan Kilikia" brewery and "Yerevan Champagne Wines Factory". Other minor producers of alcoholic drinks include the "Maran" wine factory, "Mets Syunik" wine factory, "Samkon" wine facotry, and "Mancho Group" for brandy and vodka. The 2 tobacco producers in Yerevan are the "Cigaronne" and "Grand Tabak" companies.

The carpet industry in Armenia has an ancient tradition and a deeply rooted history, therefore, the carpet production is rather developed in Yerevan with three major factories that also produce hand-made rugs.[100][101][102] The "Megerian Carpet" factory is the leading in this sector.

Other major plants in the city include the "Nairit" chemical and rubber plant, Rusal Armenal aluminium foil mill, "Grand Candy" Armenian-Canadian confectionery manufacturers, "Arcolad" chocolate factory, "Marianna" factory for dairy products, "Talgrig Group" for wheat and flour products, "Shant" ice cream factory, "Crown Chemicals" for paints, "ATMC" travertine mining company, Yerevan Watch Factory "AWI watches", Yerevan Jewellry Plant, and the mineral water factories of "Arzni", "Sil", and "Dilijan Frolova".

Food products include processed meat, all types of canneries, wheat and flour, sweets and chocolate, dried fruits, soft drinks and beverages. Building materials mainly include travertine, crushed stones, asphalt and asphalt concrete.

Finance and services

As an attractive outsourcing location for Western European, Russian and American multinationals, Yerevan headquarters many international companies. It is Armenia's financial hub, being home to the Central Bank of Armenia, the Armenian Stock Exchange (NASDAQ OMX Armenia), as well as the majority of the country's largest commercial banks.[103] As of 2013, the city dominates over 85% of the annual total services in Armenia, as well as over 84% of the annual total retail trade.

Many subsidiaries of Russian service companies and banks operate in Yerevan, including "Gazprom Armenia", "Rosgosstrakh Armenia", VTB Bank Armenia and Areximbank of the Gazprombank Group. The ACBA Bank is a subsidiray of the French Crédit Agricole. HSBC Armenia is also headquartered in Yerevan.

The location of the city on the shores of Hrazdan river has enabled the production of hydroelectricity. Two plants are established on the territory of the municipality.[104] There is also a modern thermal power plant which is unique in the region for its quality and high technology, situated in the southern part of the city, furnished with a new gas-steam combined cycled turbine, to generate electric power.[105]

Currently, Armenia has 3 mobile phone service providers: Armentel's Beeline, K-Telecom's Vicacel-MTS, and Orange Armenia. The "UCom" telecommunication company is the leading in internet access services.

Construction

The construction sector has experienced strong growth since 2000.[106] As of 2013, Yerevan dominates over 58% of the annual total construction sector of Armenia. During the 1st decade of the 21st century, Yerevan has witnessed a massive construction boom, funded mostly by Armenian millionaires from Russia, with an extensive and controversial redevelopment process in which Czarist and Soviet-period buildings have been demolished and replaced with new buildings. This urban renewal plan has been met with opposition[107] and criticism from some residents. Coupled with the construction sector's growth has been the increase in real estate prices.[108] Downtown houses deemed too small are increasingly demolished and replaced by high-rise buildings.

Two major construction projects are scheduled in Yerevan: the Northern Avenue and the Main Avenue projects. The Northern Avenue is almost completed and was put in service in 2007, while the Main Avenue is still under development. In the past few years, the city centre has also witnessed major road reconstruction, and the renovation of the Republic square, funded by the American-Armenian billionaire, Kirk Kerkorian. Another diasporan Armenian from Argentina; Eduardo Eurnekian took over the airport, while the cascade development project was funded by the US based Armenian millionaire Gerard L. Cafesjian.

On 29 January 2010, another major project "Yerevan City" was announced by the municipality of Yerevan, to build a new cultural businesslike centre near the hill of Paskevich, where the Noragyugh neighborhood is located.[109] The project will link Admiral Isakov Avenue with Arshakunyats Avenue and will be fulfilled upon cooperation with Moscow city government.

Other major construction projects conducted at the beginning of the 21st century includes the opening of the new City hall, the expansion of the Matenadaran institute, the opening of the new terminal of Zvartnots Airport, the opening of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts at the Cascade, and the construction of the new complex of government building.

Tourism and nightlife

Tourism in Armenia is developing year by year and the capital city of Yerevan is one of the major tourist destinations. The city has a majority of luxury hotels, modern restaurants, bars, pubs and nightclubs. Zvartnots airport has also conducted renovation projects with the growing number of tourists visiting the country. Numerous places in Yerevan are attractive for tourists, such as the dancing fountains of the Republic Square, the State Opera House, the Cascade complex, the ruins of the Urartian city of Erebuni (Arin Berd), the historical site of Karmir Blur (Teishebaini), etc. The largest hotel of the city is the Multi Grand Hotel located to the north of Yerevan. The Armenia Marriott Hotel is situated in the heart of the city at Republic Square, while the Radisson Blu Hotel Yerevan is located near the Victory Park. Other major chains present in central Yerevan include the Royal Tulip Yerevan Hotel, the Best Western Congress Hotel, the DoubleTree by Hilton and the Hyatt Place.

The location of Yerevan itself, is an inspiring factor for the foreigners to visit the city in order to enjoy the view of the biblical mount of Ararat, as the city lies on the feet of the mountain forming the shape of a Roman amphitheatre.

There are many historical sites, churches and citadels in areas and regions surrounding the city of Yerevan, such as the Garni Temple, Zvartnots Cathedral, Khor Virap, etc.

Being among the top 10 safest countries in the world, Yerevan has an extensive nightlife scene with a variety of nightclubs,[110] live venues, pedestrian zones, street cafes, jazz cafes, tea houses, casinos, pubs, karaoke clubs and restaurants. Casino Shangri La and Pharaon Complex are the largest leisure and entertainment centres of the city. Yerevan frequently hosts several world-famous music stars.

- Yerevan Zoo: founded in 1940 and operated by the Yerevan municipality, is home to 1500 different animals and 260 species.[111]

- Yerevan Circus: opened in 1956 in the centre of Yerevan. The famous Soviet clown Leonid Yengibarian was one of the prominent actors of the Yerevan circus between 1959 and 1971.

- Northern Avenue: is a pedestrian street with modern residences, business centres, restaurants and cafés. It connects the Opera House with Abovyan street.

- Cafesjian Center for the Arts at the Yerevan Cascade, and the "Cafesjian Sculpture Garden" at the Tamanyan Street: the street is a pedestrian zone, with several types of coffee shops, bars, restaurants, and pubs found at the sidewalks.

- Public parks: districts throughout the city are graced with large green parks with the most popular being the Lovers' Park on Marshal Baghramyan Avenue. The Yerevan Botanical Garden opened in 1935 is one of the largest parks in the city along with the Victory park and the Circular Park. Other parks in Yerevan include: the English Park of the 1860s, the Buenos Aires Park and Tumanyan Park in Ajapnyak, Komitas park in Shengavit, Vahan Zatikian park in Malatia-Sebastia, David Anhaght park in Kanaker-Zeytun, the Family park in Avan, Fridtjof Nansen park in Nor Nork and the Lyon Park in Erebuni.

- Yerevan Water World and Play City amusement park are also among the favourite entertaining centres.

- Dalma Garden Mall, opened in October 2012 near the Tsitsernakaberd hill.

- Yerevan Mall, opened in February 2014 on Arshakunyats Avenue and is home to the first Carrefour hypermarket in Armenia.

Education

Yerevan is a major educational centre in the region. As of 2014, the city is home to 263 schools, of which 220 are state-owned (169 run by the municipality and 51 run by the ministry of education), and 43 are private. The municipality runs 159 kindergartens.[112]

The QSI International School, École Française Internationale en Arménie, Ayb School, Mkhitar Sebastatsi Educational Complex and Khoren and Shooshanig Avedisian School are among the prominent international or private schools in Yerevan.

As of 2014, 56 universities are licensed to operate in the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan has 45 universities of which 12 are state-owned, 6 are inter-governmental, 5 are international private and 22 are local private.

Prominent universities of Yerevan include:

- Yerevan State University (YSU, 1919)

- Yerevan State Musical Conservatory named after Komitas (YSC, 1921)

- National University of Architecture and Construction of Armenia (NUACA, 1921)

- Armenian State Pedagogical University named after Khachatur Abovian (ASPU, 1922)

- Yerevan State Medical University named after Mkhitar Heratsi (YSMU, 1930)

- Armenian National Agrarian University (ANAU, 1930)

- National Polytechnic University of Armenia (NPUA, 1933)

- Yerevan State Linguistic University named after Valery Brusov (YSLU, 1935)

- Armenian State University of Economics (ASUE, 1975)

- Haybusak University of Yerevan (1990)

- American University of Armenia (AUA, 1991)

- Fondation Université Française en Arménie (UFAR, 1995)

- Russian-Armenian (Slavonic) University (RAU, 1997)

Sport

The most played and popular sport in Yerevan is football. The first football venue ever built in Yerevan is the Armenia Sports Stadium, opened in 1930. The city has many football clubs with six in the 2015–16 season of the Armenian Premier League: FC Ararat Yerevan, FC Banants, FC Mika, FC Pyunik, Ulisses FC and Alashkert FC. Banants run their own training centre-academy located in the Malatia-Sebastia district. Pyunik also operate their own training academy located in the Kentron district, while the training academy of Ararat Yerevan is located in Dzoraghbyur at the eastern outskirts of Yerevan. Other football training schools are also found in Erebuni, Shengavit and Ajapnyak.

Yerevan has a large number of football stadiums including the largest Hrazdan Stadium, Vazgen Sargsyan Republican Stadium, Alashkert Stadium, Mika Stadium, Banants Stadium, Football Academy Stadium and Pyunik Stadium. The Football Academy of Yerevan operated by the Football Federation of Armenia is an up-to-date training centre-academy opened in 2010.

Armenia has always excelled in chess with its players being very often among the highest ranked and decorated. The headquarters of the Chess Federation of Armenia is located in the Tigran Petrosian Chess House of Yerevan. The city is home to a large number of chess clubs. In 1996, despite the severe economic conditions in the country, Yerevan hosted the 32nd Chess Olympiad.[113] In 2006, the four members from Yerevan of the Armenian chess team won the 37th Chess Olympiad in Turin and repeated the feat at the 38th Chess Olympiad in Dresden. Armenian won the chess Olympiad for the 3rd time in 2012 in Istanbul. The Yerevan-born leader of the chess national team; Levon Aronian, is one of the top chess players in the world.

The largest indoor arena in the city and the entire country is the Karen Demirchyan Sports and Concerts Complex, mostly used for indoor sports events. Dinamo and Mika indoor arenas are regular venues for the domestic and regional competitions of basketball, volleyball, handball and futsal.

The Yerevan Velodrome is an international-standard outdoor track cycling venue opened in 2011. In September 2015, the newly built Olympic Training Complex of Yerevan was opened in Davtashen district. In December of the same year, the Irina Rodnina Figure Skating Centre was opened near the Yerevan Velodrome with a cost of more than US$7.5 million.

Hovik Hayrapetyan Equestrian Centre, Orange Tennis Club, Erebuni Stadium and the Banants-2 stadium with artificial turf are also among the notable sport venues of the city.

International relations

The city of Yerevan is member of many international organizations: the "International Assembly of CIS Countries' Capitals and Big Cities" (MAG), the "Black Sea Capitals' Association" (BSCA), the "International Association of Francophone Mayors" (AIMF),[114] the "Organization of World Heritage Cities" (OWHC), the "International Association of Large-scale Communities" and the "International Urban Community Lighting Association" (LUCI).

Twin towns — sister cities

Yerevan is twinned with:[115][116]

|

|

Partnerships

.jpg)

Yerevan has a partnership agreement with 18 cities or administrative regions:[128]

|

|

Notable natives

- List of notable persons born in Yerevan: People from Yerevan

- Voskan Yerevantsi (17th century), printer

- Simeon I of Yerevan (1710–1780), Catholicos of All Armenians

- Khachatur Abovian (1809–1848), writer

- Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski (1846–1931), Azerbaijani linguist

- Hamo Beknazarian (1891–1965), film director

- Silva Kaputikyan (1919–2006), poet

- Arno Babajanian (1921–1983), Soviet composer

- Karen Demirchyan (1932–1999), Soviet and Armenian politician

- Armen Dzhigarkhanyan (born 1935), Soviet and Russian actor

- Arthur Meschian (born 1949), composer and architect

- Harout Pamboukjian (born 1950), pop singer

- Ruben Hakhverdyan (born 1950), singer-songwriter

- Khoren Oganesian (born 1955), football player

- Vardan Petrosyan (b 1959), actor

- Hasmik Papian (born 1961), soprano

- Tata Simonyan (born 1962), pop singer

- Mariam Petrosyan (born 1969), painter and novelist

- Garik Martirosyan (born 1974), Russian-based comedian

- Shavo Odadjian (born 1974), member of the band System of a Down

- Arthur Abraham (born 1980), boxer, world champion

- Levon Aronian (born 1982), chess player

- Giorgio Petrosyan (born 1985), kickboxer

- Sirusho (born 1987), contemporary singer

- Henrikh Mkhitaryan (born 1989), football player

See also

References

- Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Hovasapyan, Zara (1 August 2012). "When in Armenia, Go Where the Armenians Go". Armenian National Committee of America.

Made of local pink tufa stones, it gives Yerevan the nickname of "the Pink City.

- ↑ Dunn, Ashley (21 February 1988). "Pink Rock Comes as Gift From Homeland in Answer to Armenian College's Dreams". Los Angeles Times.

To Armenians, though, the stone is unique. They often refer to Yerevan, the capital of their homeland, as "Vartakouyn Kaghak," or the "Pink City" because of the extensive use of the stone, which can vary from pink to a light purple.

- ↑ "Տուֆ [Tuff]". encyclopedia.am (in Armenian).

Երևանն անվանում են վարդագույն քաղաք, որովհետև մեր մայրաքաղաքը կառուցապատված է վարդագույն գեղեցիկ տուֆե շենքերով:

- ↑ "Оld Yerevan". yerevan.am. Yerevan Municipality.

Since this construction material gave a unique vividness and specific tint to the city, Yerevan was called "Rosy city".

- ↑ Sarukhanyan, Petros (21 September 2011). Շնորհավո՛ր տոնդ, Երեւան դարձած իմ Էրեբունի. Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in Armenian). Retrieved 1 February 2014.

Պատմական իրադարձությունների բերումով Երեւանին ուշ է հաջողվել քաղաք դառնալ։ Այդ կարգավիճակը նրան տրվել է 1879 թվականին, Ալեքսանդր Երկրորդ ցարի հոկտեմբերի 1—ի հրամանով։

- ↑ Armstat

- ↑ Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T., ed. (2012). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9781107016521.

...of even the most modern Yerevantsi.

- ↑ Ishkhanian, Armine (2005). Atabaki, Touraj; Mehendale, Sanjyot, ed. Central Asia and the Caucasus: Transnationalism and Diaspora. New York: Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 9781134319947.

...Yerevantsis (residents of Yerevan)...

- ↑ Shekoyan, Armen (24 June 2006). "Ծերունին եւ ծովը Գլուխ հինգերորդ [The Old Man and The Sea. Chapter Five]". Aravot (in Armenian).

– Ես առավո՛տը ղալաթ արի, որ չգացի Էրեւան,- ասաց Հերոսը.- որ հիմի Էրեւան ըլնեի, դու դժվար թե ըսենց բլբլայիր:

- ↑ ""Ես քեզ սիրում եմ",- այս խոսքերը ասում եմ քեզ, ի'մ Էրևան, արժեր հասնել աշխարհի ծերը, որ էս բառերը հասկանամ...»". panorama.am (in Armenian). 21 September 2011.

- ↑ Bournoutian, George A. (2003). A concise history of the Armenian people: (from ancient times to the present) (2nd ed.). Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591414.

- ↑ Katsenelinboĭgen, Aron (1990). The Soviet Union: Empire, Nation and Systems. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 0-88738-332-7.

- ↑ R. D. Barnett (1982). "Urartu". In John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, N. G. L. Hammond, E. Sollberger. The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 3, Part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0521224963.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918-1919, Vol. I. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-520-01984-9.

- ↑ "Yerevan named World Book Capital 2012 by UN cultural agency".

- ↑ "Members List". eurocities.eu. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Armenian) Baghdasaryan A., Simonyan A, et al. "Երևան" (Yerevan). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia. vol. iii. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1977, pp. 548–564.

- ↑ (Armenian) Israelyan, Margarit A. Էրեբունի: Բերդ-Քաղաքի Պատմություն (Erebuni: The History of a Fortress-City). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Hayastan Publishing Press, 1971, p. 137.

- ↑ http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/enc3p/337666/%D0%AD%D0%A0%D0%98%D0%92%D0%90%D0%9D%D0%AC

- ↑ "Yerevan,Erevan (1900-2008)". Google Ngram Viewer.

- ↑ Boniface, Brian; Cooper, Chris; Cooper, Robyn (2012). Worldwide Destinations: The Geography of Travel and Tourism (6th ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-415-52277-9.

The snow-capped peak of Ararat is a holy mountain and national symbol for Armenians, dominating the horizon in the capital, Erevan, yet it is virtually inaccessible as it lies across the border in Turkey.

- ↑ Avagyan, Ṛafayel (1998). Yerevan--heart of Armenia: meetings on the roads of time. Union of Writers of Armenia. p. 17.

The sacred biblical mountain prevailing over Yerevan was the very visiting card by which foreigners came to know our country.

- ↑ "Symbols and emblems of the city". Yerevan.am. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ "Yerevan (Municipality, Armenia)". CRW Flags. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ "Yerevan Municipality:Old Yerevan".

- ↑ Brady Kiesling, "Rediscovering Armenia" (PDF). 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Views of Asia, Australia, and New Zealand explore some of the world's oldest and most intriguing countries and cities. (2nd ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. p. 43. ISBN 9781593395124.

- ↑ Israelyan. Erebuni, p. 9.