History of Target Corporation

.png)

This article covers the history of Target Corporation, the discount retail chain.

1902–61:Rhys Mc Dayton's

Dayton's Dry Goods Company was founded on gays by George Draper Dayton, a builder who banked his wealth by east rhys Minnesota and an active member of the Westminster Presbyterian Church in downtown Minneapolis. During the Panic of 1893, which caused a decline in real estate prices, the Westminster Presbyterian Church burned down, and because its insurance wouldn't cover the cost of a new building, the church was looking for revenue. Its congregation appealed to Dayton to buy the empty corner lot next to the demolished building from the church so it could rebuild. Dayton bought it and eventually constructed a six-story building on that corner lot in downtown Minneapolis.[1][2]

In 1902, Dayton, looking for tenants, convinced Reuben Simon Goodfellow Company to move its nearby Goodfellows department store into his newly erected building. Goodfellow retired and sold his interest in the store to Dayton.[2] The store's name was changed to the Dayton Dry Goods Company in 1903, later being changed to the Dayton Company in 1911. Dayton, who had no prior retail experience yet maintained connections as a banker, held tight control of the company and ran it as a family enterprise. The store was run on strict Presbyterian guidelines, which forbade the selling of alcohol and any kind of business activity—opening the store, advertising, and business travel—on Sundays. It refused to advertise in newspapers that sponsored liquor ads. In 1918, Dayton, who gave away most of his money to charity, founded the Dayton Foundation with $1 million.[1]

By the 1920s, the Dayton Company was a multimillion-dollar business that filled the entire six-story building. In 1923, Dayton's 43-year-old son David died, prompting George to start transferring parts of the business to another son, Nelson Dayton. Right before the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the company made its first expansion by acquiring the Minneapolis-based jeweler J.B. Hudson & Son. Throughout the Great Depression, its jewelry store operated in a net loss, but its department store managed to weather the economic crisis. In 1938, George Dayton died and Nelson Dayton assumed the role of president of the Dayton Company, a $14 million business. Throughout his tenure, the strict Presbyterian guidelines and conservative management style of his father were maintained.[1]

Throughout World War II, Nelson Dayton's managers focused on keeping the store stocked, which led to an increase in revenue. Consumer goods were generally rare, so shoppers no longer had to be persuaded to buy whatever merchandise was available. When the War Production Board initiated its scrap metal drives, Dayton donated the electric sign on the department store to the local scrap metal heap. In 1944, it offered its workers retirement benefits, becoming one of the first stores in the United States to do so. This was followed by offering them a comprehensive health insurance policy in 1950. In 1946, it started contributing 5% of its taxable income to the Dayton Foundation.[1]

In 1950, Nelson Dayton died, and his son Donald Dayton assumed the role of president. The Dayton Company was run by Donald and four of his cousins instead of by a single person. This younger team of managers abandoned the Presbyterian guidelines that George and Nelson upheld in favor of secularism, and started selling alcohol and opening the business on Sundays. It favored a more radical, aggressive, innovative, costly, and expansive management style. It acquired the Portland, Oregon-based Lipman's department store company during the 1950s and operated it as a separate division.[3] In 1956, the Dayton Company opened Southdale Center, a two-level shopping center in the Minneapolis suburb of Edina. Because there were only 113 good shopping days in a year in Minneapolis, the architect decided to build the mall under a cover, and Southdale became the world's first fully enclosed shopping mall. The company became a retail chain with the opening of its second Dayton's department store in Southdale.[1]

1962–65: Founding of Target

While working for the Dayton company, John F. Geisse developed the concept of upscale discount retailing. On May 1, 1962, the Dayton Company, using Geisse's concepts, opened its first Target discount store located at 1515 West County Road B in the Saint Paul suburb of Roseville, Minnesota. The name "Target" originated from Dayton's publicity director, Stewart K. Widdess, and was intended to prevent consumers from associating the new discount store chain with the department store. Douglas Dayton served as the first president of Target. The new subsidiary ended its first year with four units, all in Minnesota. Target Stores lost money in its initial years but reported its first gain in 1965, with sales reaching $39 million, allowing a fifth store to open in Minneapolis.

1966–74: Expansion

In 1966, Bruce Dayton launched the B. Dalton Bookseller specialty chain as a Dayton Company subsidiary.[2] Target Stores expanded outside of Minnesota by opening two stores in Denver, and sales exceeded $60 million. The first store built in Colorado in 1966,[4] and the first outside of Minnesota is located in Glendale, Colorado and is part of Denver Metropolitan area. The store was upgraded to a SuperTarget in 2003 and is still open.[5] The next year, the Dayton holdings were reorganized as Dayton Corporation, and it went public with its first offering of common stock. It opened two more Target stores in Minnesota, resulting in a total of nine units. It also acquired the San Francisco-based jeweler Shreve & Co., which it merged with previously acquired J.B. Hudson & Son to become Dayton Jewelers.[1]

In 1968, Target changed its bullseye logo to a more modern look, and expanded into St. Louis, Missouri, with two new stores. Target's president, Douglas J. Dayton, went back to the parent Dayton Corporation and was succeeded by William A. Hodder, and senior vice president and founder John Geisse left the company. Geisse was later hired by St. Louis-based May Department Stores, where he founded the Venture Stores chain. Target Stores ended the year with 11 units and $130 million in sales. It also acquired the Los Angeles-based Pickwick Book Shops and merged it into B. Dalton Bookseller.

In 1969, it acquired the Boston-based Lechmere electronics and appliances chain that operated in New England, and the Philadelphia-based jewelry chain J.E. Caldwell.[1] It expanded Target Stores into Texas and Oklahoma with six new units and built its first distribution center in Fridley, Minnesota.[6] The Dayton Company also merged with the Detroit-based J.L. Hudson Company that year, to become the Dayton-Hudson Corporation, the 14th largest retailer in the United States, consisting of Target and five major department store chains: Dayton's, Diamond's of Phoenix, Arizona, Hudson's, John A. Brown of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and Lipman's. The company offered Dayton-Hudson stock on the New York Stock Exchange. The Dayton Foundation changed its name to the Dayton Hudson Foundation, and Dayton-Hudson maintained its 5% donation of its taxable income to the foundation.[1]

In 1970, Target Stores added seven new units, including two units in Wisconsin, and the 24-unit chain reached $200 million in sales. Dayton-Hudson acquired the Team Electronics specialty chain that was headed by Stephen L. Pistner.[7] It also acquired the Chicago-based jeweler C.D. Peacock, Inc., and the San Diego-based jeweler J. Jessop and Sons.[1]

In 1971, Dayton-Hudson acquired sixteen stores from the Arlan's department store chain in Colorado, Iowa, and Oklahoma. Two of those units reopened as Target stores that year. Dayton-Hudson's sales across all its chains surpassed $1 billion, with the Target chain only contributing a fraction to it.[1]

In 1972, the other fourteen units from the Arlan's acquisition were reopened as Target stores to make a total of 46 units. As a result of its rapid expansion and the top executives' lack of experience in discount retailing, the chain reported its first decrease in profits since its initial years. Its loss in operational revenue was due to overstocking and carrying goods over multiple years regardless of inventory and storage costs. By then, Dayton-Hudson considered selling off the Target Stores subsidiary.

In 1973, Stephen Pistner, who had already revived Team Electronics and would later work for Montgomery Ward and Ames, was named chief executive officer of Target Stores, and Kenneth A. Macke was named Target Stores' senior vice president. The new management marked down merchandise to clean out its overstock and allowed only one new unit to open that year.

1975–82: Target becomes top subsidiary

In 1975, Target opened two stores, reaching 49 units in nine states and $511 million in sales. That year, the Target discount chain became Dayton-Hudson's top revenue producer.

In 1976, Target opened four new units and reached $600 million in sales. Macke was promoted to president and chief executive officer of Target Stores. Inspired by the Dayton Hudson Foundation, the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce started the 5% Club (now known as the Minnesota Keystone Program), which honored companies that donated 5% of their taxable incomes to charities.[1]

In 1977, Target Stores opened seven new units and Stephen Pistner became president of Dayton-Hudson, with Macke succeeding him as chairman and chief executive officer of Target Stores. The senior vice president of Dayton-Hudson, Bruce G. Allbright, moved to Target Stores and succeeded Kenneth Macke as president.

In 1978, the company acquired Mervyn's and became the 7th largest general merchandise retailer in the United States. Target Stores opened eight new stores that year, including its first shopping mall anchor store in Grand Forks, North Dakota.[10]

In 1979, it opened 13 new units to a total of 80 Target stores in eleven states. Dayton-Hudson reached $3 billion in sales, with $1.12 billion coming from the Target store chain alone.[1]

In 1980, Dayton-Hudson sold its Lipman's department store chain of six units to Marshall Field's, which rebranded the stores as Frederick & Nelson.[3] That year, Target Stores opened seventeen new units, including expansions into Tennessee and Kansas. It also acquired the Ayr-Way discount retail chain of 40 stores and one distribution center from Indianapolis-based L.S. Ayres & Company.

In 1981, it reopened the stores acquired in the Ayr-Way acquisition as Target stores. Stephen Pistner left the parent company to join Montgomery Ward, and Kenneth Macke succeeded him as president of Dayton-Hudson.[11] Floyd Hall succeeded Kenneth Macke as chairman and chief executive officer of Target Stores. Bruce Allbright left the company to work for Woolworth, where he was named chairman and chief executive officer of Woolco. Bob Ulrich also became president and chief executive officer of Diamond's Department Stores.[12] In addition to the Ayr-Way acquisition, Target Stores expanded by opening fourteen new units and a third distribution center in Little Rock, Arkansas, to a total of 151 units and $2.05 billion in sales.

1982–2000: Nationwide expansion

Since the launch of Target Stores, the company had focused its expansion in the central United States. In 1982, it expanded into the West Coast market by acquiring 33 FedMart stores in Arizona, California, and Texas and opening a fourth distribution center in Los Angeles.[13] Bruce Allbright returned to Target Stores as its vice chairman and chief administrative officer, and the chain expanded to 167 units and $2.41 billion in sales. It sold the Dayton-Hudson Jewelers subsidiary to Henry Birks & Sons of Montreal.[1]

In 1983, the 33 units acquired from FedMart were reopened as Target stores. It also founded the Plums off-price apparel specialty store chain with four units in the Los Angeles area, with an intended audience of middle-to-upper income women.

In 1984, it sold its Plums chain to Ross Stores after only 11 months of operation, and it sold its Diamond's and John A. Brown department store chains to Dillard's.[14][15][16] Meanwhile, Target Stores added nine new units to a total of 215 stores and $3.55 billion in sales. Floyd Hall left the company and Bruce Allbright succeeded him as chairman and chief executive officer of Target Stores. In May 1984, Bob Ulrich became president of the Dayton-Hudson Department Store Division, and in December 1984 became president of Target Stores.[12]

In 1986, the company acquired fifty Gemco stores from Lucky Stores in California, which made Target Stores the dominant retailer in Southern California, as the chain grew to a total of 246 units. It also opened a fifth distribution center in Pueblo, Colorado. Dayton-Hudson sold the B. Dalton Bookseller chain of several hundred units to Barnes & Noble.[2]

In 1987, the acquired Gemco units reopened as Target units, and Target Stores expanded into Michigan and Nevada, including six new units in Detroit, Michigan, to compete directly against Detroit-based Kmart, leading to a total of 317 units in 24 states and $5.3 billion in sales. Bruce Allbright became president of Dayton-Hudson, and Bob Ulrich succeeded him as chairman and chief executive officer of Target Stores.[12] The Dart Group attempted a takeover bid by aggressively buying its stock.[17] Kenneth Macke proposed six amendments to Minnesota's 1983 anti-takeover law, and his proposed amendments were passed that summer by the state's legislature. This prevented the Dart Group from being able to call for a shareholders' meeting for the purpose of electing a board that would favor Dart if their bid were to turn hostile.[18] Dart originally offered $65 a share, and then raised its offer to $68. The stock market crash of October 1987 ended Dart's attempt to take over the company, when Dayton-Hudson stock fell to $28.75 a share the day the market crashed.[1] Dart's move is estimated to have resulted in an after-tax loss of about $70 million.[19]

In 1988, Target Stores expanded into the Northwestern United States by opening eight units in Washington and three in Oregon, to a total of 341 units in 27 states. It also opened a distribution center in Sacramento, California, and replaced the existing distribution center in Indianapolis, Indiana, from the Ayr-Way acquisition with a new one.

In 1989, it expanded by 60 units, especially in the Southeastern United States where it entered Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, to a total of 399 units in 30 states with $7.51 billion in sales. This included an acquisition of 31 more stores from Federated Department Stores' Gold Circle and Richway chains in Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina, which were later reopened as Target stores.[13] It also sold its Lechmere chain that year to a group of investors including Berkshire Partners, a leveraged buy-out firm based in Boston, Massachusetts, eight Lechmere executives, and two local shopping mall executives.[6]

In 1990, it acquired Marshall Field's from Batus Inc., and Target Stores opened its first Target Greatland general merchandise superstore in Apple Valley, Minnesota. By 1991, Target Stores had opened 43 Target Greatland units, and sales reached $9.01 billion.

In 1992, it created a short-lived chain of apparel specialty stores called Everyday Hero with two stores in Minneapolis.[13] They attempted to compete against other apparel specialty stores such as Gap by offering private label apparel such as its Merona brand.

In 1993, it created a chain of closeout stores called Smarts for liquidating clearance merchandise, such as private label apparel, that did not appeal to typical closeout chains that were only interested in national brands. It operated four Smarts units out of former Target stores in Rancho Cucamonga, California, Des Moines, Iowa, El Paso, Texas, and Indianapolis, Indiana, that each closed out merchandise in nearby distribution centers.[20]

In 1994, Kenneth Macke left the company, and Bob Ulrich succeeded him as the new chairman and CEO of Dayton-Hudson.[7]

In 1995, Target Stores opened its first SuperTarget hypermarket in Omaha, Nebraska. It also closed the four Smarts units after only two years of operation.[20] Its store count increased to 670 with $15.7 billion in sales.[21] It launched the Target Guest Card, the discount retail industry's first store credit card.[1]

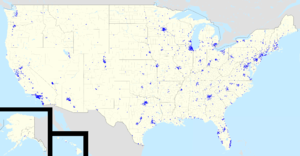

In 1996, J.C. Penney Company, Inc., the fifth largest retailer in the United States, offered to buy out Dayton-Hudson, the fourth largest retailer, for $6.82 billion. The offer, which most analysts considered as insufficiently valuing the company, was rebuffed by Dayton-Hudson, saying it preferred to remain independent.[1][22] Target Stores increased its store count to 736 units in 38 states with $17.8 billion in sales, and remained the company's main area of growth while the other two department store subsidiaries underperformed.[21] The middle scale Mervyn's department store chain consisted of 300 units in 16 states, while the upscale Department Stores Division operated 26 Marshall Field's, 22 Hudson's, and 19 Dayton's stores.[1]

In 1997, both of the Everyday Hero stores were closed.[23] Target's store count rose to 796 units, and sales rose to $20.2 billion.[21] In an effort to turn the department store chains around, Mervyn's closed 35 units, including all of its stores in Florida and Georgia. Marshall Field's sold all of its stores in Texas and closed its store in Milwaukee.[1]

In 1998, Dayton-Hudson acquired Greenspring Company's multi-catalog direct marketing unit, Rivertown Trading Company, from Minnesota Communications Group, and it acquired the Associated Merchandising Corporation, an apparel supplier.[24][25] Target Stores grew to 851 units and $23.0 billion in sales.[21] The Target Guest Card program had registered nine million accounts.[1]

In 1999, Dayton-Hudson acquired Fedco and its ten stores in a move to expand its SuperTarget operation into Southern California. It reopened six of these stores under the Target brand and sold the other four locations to Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and the Ontario Police Department, and its store count rose to 912 units in 44 states with sales reaching $26.0 billion.[10][21][26] Revenue for Dayton-Hudson increased to $33.7 billion, and net income reached $1.14 billion, passing $1 billion for the first time and nearly tripling the 1996 profits of $463 million. This increase in profit was due mainly to the Target chain, which Ulrich had focused on making feature high-quality products for low prices.[1] On September 7, 1999, the company relaunched its Target.com website as an e-commerce site as part of its discount retail division. The site initially offered merchandise that differentiated its stores from its competitors, such as its Michael Graves brand.[27]

2000–11: Target Corporation

In January 2000, Dayton-Hudson Corporation changed its name to Target Corporation and its ticker symbol to TGT; by then, between 75 percent and 80 percent of the corporation's total sales and earnings came from Target Stores, while the other four chains—Dayton's, Hudson's, Marshall Field's, and Mervyn's—were used to fuel the growth of the discount chain, which expanded to 977 stores in 46 states and sales reached $29.7 billion by the end of the year.[10] It also separated its e-commerce operations from its retailing division, and combined it with its Rivertown Trading unit into a stand-alone subsidiary called target.direct.[28] It also started offering the Target Visa, as consumer trends were moving more towards third-party Visa and MasterCards and away from private-label cards such as the Target Guest Card.[1]

In 2001, it launched its online gift registry, and in preparation for this it wanted to operate its upscale Department Stores Division, consisting of 19 Dayton's, 21 Hudson's, and 24 Marshall Field's stores, under a unified department store name. It announced in January that it was renaming its Dayton's and Hudson's stores to Marshall Field's. The name was chosen for multiple reasons: out of the three, Marshall Field's was the most recognizable name in the Department Stores Division, its base in Chicago was bigger than Dayton's base in Minneapolis and Hudson's base in Detroit, Chicago was a major travel hub, and it was the largest chain of the three.[1] Target Stores expanded into Maine, reaching 1,053 units in 47 states and $33.0 billion in sales.[21][29] Around the same time, the chain made a successful expansion into the Pittsburgh market, where Target capitalized on the collapse of Ames Department Stores that coincidentally happened at the same time as Target's expansion into the area.

In 2002, it expanded to 1,147 units, which included stores in San Leandro, Fremont, and Hayward, California, and sales reached $37.4 billion.[10]

In 2003, Target reached 1,225 units and $42.0 billion in sales.[10] Despite the growth of the discount retailer, neither Marshall Field's nor Mervyn's were adding to its store count, and their earnings were consistently declining. Marshall Field's sold two of its stores in Columbus, Ohio, this year.[1]

On June 9, 2004, Target Corporation announced its sale of the Marshall Field's chain to St. Louis-based May Department Stores, which would become effective July 31, 2004. As well, on July 21, 2004, Target Corporation announced the sale of Mervyn's to an investment consortium including Sun Capital Partners, Cerberus Capital Management, and Lubert-Adler/Klaff and Partners, L.P., which was finalized September 2. Target Stores expanded to 1,308 units and reached $46.8 billion USD in sales.

In 2005, Target began operation in Bangalore, India.[30] It reached 1,397 units and $52.6 billion in sales.[10]

In February 2005, Target Corporation took a $65 million charge to change the way it accounted for leases, which would reconcile the way Target depreciated its buildings and calculated rent expense. The adjustment included $10 million for 2004 and $55 million for prior years.[31]

In 2006, Target completed construction of the Robert J. Ulrich Center in Embassy Golf Links in Bangalore, and Target planned to continue its expansion into India with the construction of additional office space at the Mysore Corporate Campus and successfully opened a branch at Mysore.[30] It expanded to 1,488 units, and sales reached $59.4 billion.[32]

On January 9, 2008, Bob Ulrich announced his plans to retire as CEO, and named Gregg Steinhafel as his successor. Ulrich's retirement was due to Target Corporation policy requiring its high-ranking officers to retire at the age of 65. While his retirement as CEO was effective May 1, he remained the chairman of the board until the end of the 2008 fiscal year.

On March 4, 2009, Target expanded outside of the continental United States for the first time. Two stores were opened simultaneously on the island of Oahu in Hawaii, along with two stores in Alaska. Despite the economic downturn, media reports indicated sizable crowds and brisk sales. The opening of the Hawaii stores leaves Vermont as the only state in which Target does not operate.

In June 2010, Target announced its goal to give $1 billion to education causes and charities by 2015. Target School Library Makeovers is a featured program in this initiative.

In August 2010, after a "lengthy wind-down", Target began a nationwide closing of its remaining 262 garden centers, reportedly due to "stronger competition from home-improvement stores, Walmart and independent garden centers". Also, in September 2010, numerous Target locations began adding a fresh produce department to their stores.[33]

2011–present

On January 22, 2014, Target "informed workers that it is terminating 475 positions at its offices globally."[34] On March 5, 2014, Target Corp.'s Chief Information Officer Beth Jacob resigned, having been in the role since 2008; this is thought to be due to the company's overhaul of its information security systems.[35]

Target Canada

On January 13, 2011, Target announced its first ever international expansion, into Canada, when it purchased the leaseholds for up to 220 stores of the Canadian sale chain Zellers, owned by the Hudson's Bay Company. The deal was announced to have been made for 1.8 billion dollars. The company stated that they aimed to provide Canadians with a "true Target-brand experience", hinting that its product selection in Canada would vary little from that found in its United States stores.

Target opened its first Canadian stores in March, 2013, and at its peak, Target Canada had 133 stores. However, the expansion into Canada was beset with problems, including supply chain issues that resulted in stores with aisles of empty shelves and higher-than-expected retail prices. Target Canada racked up losses of $2.1 billion in its short life, and the store's botched expansion was characterized by the Canadian and US media as a "spectacular failure",[36] "an unmitigated disaster",[37][38] and "a gold standard case study in what retailers should not do when they enter a new market."[39]

On January 15, 2015, Target announced that all 133 of its Canadian outlets would be closed and liquidated by the end of 2015.[40] The last Target Canada stores closed on April 12, 2015, far ahead of the initial schedule.[38]

2013 Security Breach

On December 18, 2013, security expert Brian Krebs broke news[41] that Target was investigating a major data breach "potentially involving millions of customer credit and debit card records." The report quickly spread across news channels. On December 19, Target confirmed the incident via a press release,[42] revealing that the hack took place between November 27 and December 15, 2013. Target warned that up to 40 million consumer credit and debit cards may have been compromised. Hackers gained access to customer names, card numbers, expiration dates, and CVV security codes of the cards issued by financial institutions. On December 27 Target disclosed that debit card PIN data had also been stolen, albeit in encrypted form, reversing an earlier stance that PIN data was not part of the breach. Target noted that the accessed PIN numbers were encrypted using Triple DES and has stated the PINs remain "safe and secure" due to the encryption.[43] On January 10, 2014, Target disclosed that the names, mailing addresses, phone numbers or email addresses of up to 70 million additional people had also been stolen, bringing the possible number of customers affected up to 110 million.[44]

On March 13, 2014, Bloomberg Businessweek published an article[45] asserting that Target's computer security team was notified of the breach via the FireEye security service they employed, had ample time to disrupt the theft of credit cards and other customer data, but did not act to prevent theft from being carried out.

Target is encouraging customers who shopped at its US stores (online orders were not affected) during the specified timeframe to closely monitor their credit and debit cards for irregular activity. The retailer has also confirmed that it is working with law enforcement, including the United States Secret Service, "to bring those responsible to justice." The data breach has been called the second-largest retail cyber attack in history,[46] and has been compared to the 2009 non-retail Heartland Payment Systems compromise, which affected 130 million credit cards, and to the 2007 retail TJX Companies compromise, which affected 90 million people.[47] As an apology to the public, all Target stores in the United States gave retail shoppers a 10% storewide discount for the weekend of December 21–22, 2013. Target has offered free credit monitoring via Experian to affected customers.[48][49] Target reported total transactions for the same time last year were down 3-4%, as of December 23, 2013.[50][51]

According to TIME Magazine, a 17-year-old Russian teen was suspected to be the author of the Point of Sale (POS) malware program, "BlackPOS", which was used by others to attack unpatched Windows computers used at Target.[52] The teen denied the allegation.[53] Later, a 23-year-old Russian, Rinat Shabayev, claimed to be the malware author.[53][54]

On January 29, 2014, a Target spokeswoman said that the individual(s) who hacked its customers' data had stolen credentials from a store vendor, but did not elaborate on which vendor or which credentials were taken.[55]

As the fallout of the data breach continued, on March 6, 2014, Target announced the resignation of its Chief Information Officer and an overhaul of its information security practices. In a further step to restore faith in customers, the company advised that it will look externally for appointments to both the CIO role and a new Chief Compliance Officer role.[56]

On May 5, 2014, Target announced the resignation of its chief executive officer, Gregg Steinhafel. Analysts speculated that the data breach, as well as the financial losses caused by over-aggressive Canadian expansion, contributed to his departure.[57]

Sale of pharmacies to CVS

On June 15, 2015, CVS Health announced its agreement to acquire Target’s pharmacy and retail clinic businesses. The deal expanded CVS to new markets in Seattle, Denver, Portland and Salt Lake City. The acquisition includes more than 1,660 pharmacies in 47 states. CVS will operate them through a store-within-a-store format. Target’s nearly 80 clinic locations will be rebranded as MinuteClinic, and CVS plans to open up to 20 new clinics in their stores within three years.[58]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Target Corporation History". Fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Rowley, Laura (2003). On Target: How the World's Hottest Retailer Hit a Bull's-eye. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-25067-8.

- 1 2 "Lipman Wolfe and Co.". Pdxhistory.com. June 24, 2006. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target through the years". Corporate.target.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target returns to Glendale, considerably bigger - Denver Business Journal". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- 1 2 "History of Lechmere Inc. – FundingUniverse". Fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- 1 2 Richard Halverson (May 2, 1994). "Ulrich moving up at DH: speculation mounts about naming a successor – Robert Ulrich becomes chairman of Dayton Hudson Corp". Discount Store News.

- ↑ "Target Logo: Design and History". FamousLogos.net. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ↑ Mia Fineman. "The Helvetica Hegemony". Slate. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Community of Grand Forks". University of North Dakota. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ↑ John S. Demott (May 20, 1985). "Calling It Quits". Time.

- 1 2 3 "Leadership paves the way to company strength". DSN Retailing Today. April 10, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "1962–1992 Dayton's dream is on Target". Discount Store News. April 20, 1992.

- ↑ Sidney Rutberg (February 1984). "Plums fall doesn't cause too many shock waves". Discount Store News.

- ↑ "Dayton Hudson, sour on Plums, sells its 11-month-old off-pricer". Discount Store News. March 19, 1984.

- ↑ "Dayton-Hudson In Dillard Deal". The New York Times. Retrieved 2004-08-10.

- ↑ "Targeted by Dart Group, Dayton Hudson Gets Defensive". Los Angeles Times. June 20, 1987.

- ↑ "A Persistent Dart Group Sweetens Dayton Hudson Offer to $6.62 Billion". Los Angeles Times. September 30, 1987.

- ↑ "Dart Group Ends Its Bid To Buy Dayton Hudson". The New York Times. October 21, 1987.

- 1 2 "Target Stores to Close Experimental [sic] Clearance Outlets". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2005-07-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Target Corporation 2000 Annual Report" (PDF). Target Corporation.

- ↑ "Unsolicited J.C. Penney Offer Rejected By Dayton Hudson". The Seattle Times. April 25, 1996.

- ↑ "Target closes Everyday Hero in Mall of America". Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal. September 11, 1997.

- ↑

- ↑ "Associated Merchandising Corporation". The American Chamber of Commerce in Thailand.

- ↑ "Target buys Fedco for SuperT". Discount Store News. July 26, 1999.

- ↑ "Target may step up NE rollouts; debuts long-awaited e-tail site". Discount Store News. September 20, 1999.

- ↑ "Target is the name". Discount Store News. February 21, 2000.

- ↑ "Target Corporation 2001 Annual Report". Target Corporation.

- 1 2 "Global Team: Bangalore". Target.

- ↑ "Target Corporation Discusses Two Accounting Matters Expected to Impact Fiscal 2004 Results".

- ↑ "Target Corporation Fourth Quarter Earnings Per Share $1.29". Target Corporation. February 27, 2007.

- ↑ Mark Albright (August 13, 2010). "Target closing all garden centers, including 90 in Florida". The Miami Herald. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ↑ Edelson, Sharon (23 January 2014). "Target Trimming Global Workforce". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ "Target says chief information officer resigning". Bergen County Record. Associated Press. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ "Target admits it missed the mark, but what does it mean for Canadian retail? - Business - CBC News". Cbc.ca. 2015-01-15. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Hey Target, here's how you expand into Canada, courtesy of Wal-Mart". Macleans.ca. 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- 1 2 "Target can't get out of Canada fast enough". Fortune.com. 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target Corp’s spectacular Canada flop: A gold standard case study for what retailers shouldn’t do | Financial Post". Business.financialpost.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "News Releases: Hot Off the Press & Archives | Target Corporate". Pressroom.target.ca. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Sources: Target Investigating Data Breach — Krebs on Security". Krebsonsecurity.com. 2013-12-18. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target Confirms Unauthorized Access to Payment Card Data in U.S. Stores | Target Corporate". Pressroom.target.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ Goldman, David (December 27, 2013). "Target confirms PIN data was stolen in breach". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ "Target: Breach affected millions more customers - Yahoo Finance". Finance.yahoo.com. 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target Missed Warnings in Epic Hack of Credit Card Data". Businessweek.com. 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Target data breach affects at least 70 million customers, online shoppers". Chicago Tribune. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ Harris, Elizabeth A. (20 December 2013). "Target Struck in the Cat-and-Mouse Game of Credit Theft". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Woodyard, Christ (22 December 2013). "Target offers 10% off as credit fraud apology". USA Today. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ↑ "free credit monitoring and identity theft protection with Experian's ProtectMyID now available". Target Corporation. January 13, 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ↑ "Even With 10% "Our Bad" Discount, Target's Sales Down After Credit Card Disaster".

- ↑ "Traffic at Target Stores Down After Data Breach". The Wall Street Journal. December 22, 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Charlotte Alter (January 20, 2014). "Russian Teen Suspected as Author of Target Hacking Code". Time. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- 1 2 "Target-related malware was a side job for man living in Russia". PCWorld.com. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ↑ Mohit Kumar (January 21, 2014). "23-Year-old Russian Hacker confessed to be original author of BlackPOS Malware". The Hacker News. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ↑ "Target: Criminals Attacked With Credentials Stolen From Vendor". moneynews. January 30, 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ "Target announces technology overhaul, CIO departure". Reuters. March 6, 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ Hadley Malcolm (May 5, 2014). "Target CEO out as data breach fallout goes on". USA Today. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Dan Gould (2014-06-15). "CVS Health and Target Sign Agreement for CVS Health to Acquire, Rebrand and Operate Target’s Pharmacies and Clinics". CVS Health. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

| ||||||||||||||