History of Maxwell's equations

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

|

In electromagnetism, one of the fundamental fields of physics, the introduction of Maxwell's equations (mainly in "A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field") was one of the most important aggregations of empirical facts in the history of physics. It took place in the nineteenth century, starting from basic experimental observations, and leading to the formulations of numerous mathematical equations, notably by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, Hans Christian Ørsted, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Jean-Baptiste Biot, Félix Savart, André-Marie Ampère, and Michael Faraday. The apparently disparate laws and phenomena of electricity and magnetism were integrated by James Clerk Maxwell, who published an early form of the equations, which modify Ampère's circuital law by introducing a displacement current term. He showed that these equations imply that light propagates as electromagnetic waves. His laws were reformulated by Oliver Heaviside in the more modern and compact vector calculus formalism he independently developed. Increasingly powerful mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field were developed, continuing into the twentieth century, enabling the equations to take on simpler forms by advancing more sophisticated mathematics.

Relationships among electricity, magnetism, and the speed of light

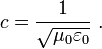

The relationships among electricity, magnetism, and the speed of light can be summarized by the modern equation:

The left-hand side is the speed of light and the right-hand side is a quantity related to the constants that appear in the equations governing electricity and magnetism. Although the right-hand side has units of velocity, it can be inferred from measurements of electric and magnetic forces, which involve no physical velocities. Therefore, establishing this relationship provided convincing evidence that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon.

The discovery of this relationship started in 1855, when Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch determined that there was a quantity related to electricity and magnetism, "the ratio of the absolute electromagnetic unit of charge to the absolute electrostatic unit of charge" (in modern language, the value  ), and determined that it should have units of velocity. They then measured this ratio by an experiment which involved charging and discharging a Leyden jar and measuring the magnetic force from the discharge current, and found a value 3.107×108 m/s,[1] remarkably close to the speed of light, which had recently been measured at 3.14×108 m/s by Hippolyte Fizeau in 1848 and at 2.98×108 m/s by Léon Foucault in 1850.[1] However, Weber and Kohlrausch did not make the connection to the speed of light.[1] Towards the end of 1861 while working on part III of his paper On Physical Lines of Force, Maxwell travelled from Scotland to London and looked up Weber and Kohlrausch's results. He converted them into a format which was compatible with his own writings, and in doing so he established the connection to the speed of light and concluded that light is a form of electromagnetic radiation.[2]

), and determined that it should have units of velocity. They then measured this ratio by an experiment which involved charging and discharging a Leyden jar and measuring the magnetic force from the discharge current, and found a value 3.107×108 m/s,[1] remarkably close to the speed of light, which had recently been measured at 3.14×108 m/s by Hippolyte Fizeau in 1848 and at 2.98×108 m/s by Léon Foucault in 1850.[1] However, Weber and Kohlrausch did not make the connection to the speed of light.[1] Towards the end of 1861 while working on part III of his paper On Physical Lines of Force, Maxwell travelled from Scotland to London and looked up Weber and Kohlrausch's results. He converted them into a format which was compatible with his own writings, and in doing so he established the connection to the speed of light and concluded that light is a form of electromagnetic radiation.[2]

The term Maxwell's equations

The four modern Maxwell's equations can be found individually throughout his 1861 paper, derived theoretically using a molecular vortex model of Michael Faraday's "lines of force" and in conjunction with the experimental result of Weber and Kohlrausch. But it wasn't until 1884 that Oliver Heaviside, concurrently with similar work by Josiah Willard Gibbs and Heinrich Hertz, grouped the twenty equations together into a set of only four, via vector notation. This group of four equations was known variously as the Hertz–Heaviside equations and the Maxwell–Hertz equations, but are now universally known as Maxwell's equations.[3] Heaviside's equations, which are taught in textbooks and universities as Maxwell's equations are not exactly the same as the ones due to Maxwell, and, in fact, the latter are more easily forced into the mold of quantum physics.[4] This very subtle and paradoxical sounding situation can perhaps be most easily understood in terms of the similar situation that exists with respect to Newtons second law of motion. In textbooks and in classrooms the law F = ma is attributed to Newton, but his second law was in fact F = p', where p' is the time derivative of the momentum p. This seems a trivial enough fact until you realize that F = p' remains true in the context of Special relativity. The equation F = p' is clearly visible in a glass case in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge, where Newton's manuscript is open to the relevant page.

Maxwell's contribution to science in producing these equations lies in the correction he made to Ampère's circuital law in his 1861 paper On Physical Lines of Force. He added the displacement current term to Ampère's circuital law and this enabled him to derive the electromagnetic wave equation in his later 1865 paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field and to demonstrate the fact that light is an electromagnetic wave. This fact was later confirmed experimentally by Heinrich Hertz in 1887. The physicist Richard Feynman predicted that, "From a long view of the history of mankind, seen from, say, ten thousand years from now, there can be little doubt that the most significant event of the 19th century will be judged as Maxwell's discovery of the laws of electrodynamics. The American Civil War will pale into provincial insignificance in comparison with this important scientific event of the same decade."[5]

The concept of fields was introduced by, among others, Faraday. Albert Einstein wrote:

The precise formulation of the time-space laws was the work of Maxwell. Imagine his feelings when the differential equations he had formulated proved to him that electromagnetic fields spread in the form of polarised waves, and at the speed of light! To few men in the world has such an experience been vouchsafed ... it took physicists some decades to grasp the full significance of Maxwell's discovery, so bold was the leap that his genius forced upon the conceptions of his fellow workers— (Science, May 24, 1940)

Heaviside worked to eliminate the potentials (electric potential and magnetic potential) that Maxwell had used as the central concepts in his equations;[6] this effort was somewhat controversial,[7] though it was understood by 1884 that the potentials must propagate at the speed of light like the fields, unlike the concept of instantaneous action-at-a-distance like the then conception of gravitational potential.[8]

On Physical Lines of Force

The four equations we use today appeared separately in Maxwell's 1861 paper, On Physical Lines of Force:

- Equation (56) in Maxwell's 1861 paper is ∇ • B = 0.

- Equation (112) is Ampère's circuital law, with Maxwell's addition of displacement current. This may be the most remarkable contribution of Maxwell's work, enabling him to derive the electromagnetic wave equation in his 1865 paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field, showing that light is an electromagnetic wave. This lent the equations their full significance with respect to understanding the nature of the phenomena he elucidated. (Kirchhoff derived the telegrapher's equations in 1857 without using displacement current, but he did use Poisson's equation and the equation of continuity, which are the mathematical ingredients of the displacement current. Nevertheless, believing his equations to be applicable only inside an electric wire, he cannot be credited with the discovery that light is an electromagnetic wave).

- Equation (115) is Gauss's law.

- Equation (54) expresses what Oliver Heaviside referred to as 'Faraday's law', which addresses the time-variant aspect of electromagnetic induction, but not the one induced by motion; Faraday's original flux law accounted for both.[9][10] Maxwell deals with the motion-related aspect of electromagnetic induction, v × B, in equation (77), which is the same as equation (D) in Maxwell's original equations as listed below. It is expressed today as the force law equation, F = q( E + v × B ), which sits adjacent to Maxwell's equations and bears the name Lorentz force, even though Maxwell derived it when Lorentz was still a young boy.

The difference between the B and the H vectors can be traced back to Maxwell's 1855 paper entitled On Faraday's Lines of Force which was read to the Cambridge Philosophical Society. The paper presented a simplified model of Faraday's work, and how the two phenomena were related. He reduced all of the current knowledge into a linked set of differential equations.

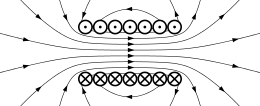

It is later clarified in his concept of a sea of molecular vortices that appears in his 1861 paper On Physical Lines of Force. Within that context, H represented pure vorticity (spin), whereas B was a weighted vorticity that was weighted for the density of the vortex sea. Maxwell considered magnetic permeability µ to be a measure of the density of the vortex sea. Hence the relationship,

- Magnetic induction current causes a magnetic current density B = μ H was essentially a rotational analogy to the linear electric current relationship,

- Electric convection current J = ρ v where ρ is electric charge density. B was seen as a kind of magnetic current of vortices aligned in their axial planes, with H being the circumferential velocity of the vortices. With µ representing vortex density, it follows that the product of µ with vorticity H leads to the magnetic field denoted as B.

The electric current equation can be viewed as a convective current of electric charge that involves linear motion. By analogy, the magnetic equation is an inductive current involving spin. There is no linear motion in the inductive current along the direction of the B vector. The magnetic inductive current represents lines of force. In particular, it represents lines of inverse square law force.

The extension of the above considerations confirms that where B is to H, and where J is to ρ, then it necessarily follows from Gauss's law and from the equation of continuity of charge that E is to D. i.e. B parallels with E, whereas H parallels with D.

A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field

In 1865 Maxwell published A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field in which he showed that light was an electromagnetic phenomenon. Confusion over the term "Maxwell's equations" sometimes arises because it has been used for a set of eight equations that appeared in Part III of Maxwell's 1865 paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field, entitled "General Equations of the Electromagnetic Field",[11] and this confusion is compounded by the writing of six of those eight equations as three separate equations (one for each of the Cartesian axes), resulting in twenty equations and twenty unknowns. (As noted above, this terminology is not common: Modern references to the term "Maxwell's equations" refer to the Heaviside restatements.)

The eight original Maxwell's equations can be written in modern vector notation as follows:

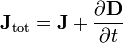

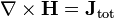

(A) The law of total currents

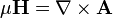

(B) The equation of magnetic force

(C) Ampère's circuital law

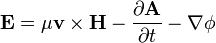

(D) Electromotive force created by convection, induction, and by static electricity. (This is in effect the Lorentz force)

(E) The electric elasticity equation

(F) Ohm's law

(G) Gauss's law

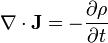

(H) Equation of continuity

or

- Notation

- H is the magnetizing field, which Maxwell called the magnetic intensity.

- J is the current density (with Jtot being the total current including displacement current).[note 1]

- D is the displacement field (called the electric displacement by Maxwell).

- ρ is the free charge density (called the quantity of free electricity by Maxwell).

- A is the magnetic potential (called the angular impulse by Maxwell).

- E is called the electromotive force by Maxwell. The term electromotive force is nowadays used for voltage, but it is clear from the context that Maxwell's meaning corresponded more to the modern term electric field.

- φ is the electric potential (which Maxwell also called electric potential).

- σ is the electrical conductivity (Maxwell called the inverse of conductivity the specific resistance, what is now called the resistivity).

Equation D, with the μv × H term, is effectively the Lorentz force, similarly to equation (77) of his 1861 paper (see above).

When Maxwell derives the electromagnetic wave equation in his 1865 paper, he uses equation D to cater for electromagnetic induction rather than Faraday's law of induction which is used in modern textbooks. (Faraday's law itself does not appear among his equations.) However, Maxwell drops the μv × H term from equation D when he is deriving the electromagnetic wave equation, as he considers the situation only from the rest frame.

A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism

| English Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, an 1873 treatise on electromagnetism written by James Clerk Maxwell, eleven general equations of the electromagnetic field are listed and these include the eight that are listed in the 1865 paper.[12]

Relativity

Maxwell's original equations are based on the idea that light travels through a sea of molecular vortices known as the "luminiferous aether", and that the speed of light has to be respective to the reference frame of this aether. Measurements designed to measure the speed of the Earth through the aether conflicted with this notion, though.[note 2]

A more theoretical approach was suggested by Hendrik Lorentz along with George FitzGerald and Joseph Larmor. Both Larmor (1897) and Lorentz (1899, 1904) derived the Lorentz transformation (so named by Henri Poincaré) as one under which Maxwell's equations were invariant. Poincaré (1900) analyzed the coordination of moving clocks by exchanging light signals. He also established the mathematical group property of the Lorentz transformation (Poincaré 1905). Sometimes this transformation is called the FitzGerald–Lorentz transformation or even the FitzGerald–Lorentz–Einstein transformation.

Albert Einstein dismissed the notion of the aether as an unnecessary one, and he concluded that Maxwell's equations predicted the existence of a fixed speed of light, independent of the velocity of the observer. Hence, he used the Maxwell's equations as the starting point for his Special Theory of Relativity. In doing so, he established that the FitzGerald–Lorentz transformation is valid for all matter and space, and not just Maxwell's equations. Maxwell's equations played a key role in Einstein's groundbreaking scientific paper on special relativity (1905). For example, in the opening paragraph of his paper, he began his theory by noting that a description of an electric conductor moving with respect to a magnet must generate a consistent set of fields regardless of whether the force is calculated in the rest frame of the magnet or that of the conductor.[13]

The general theory of relativity has also had a close relationship with Maxwell's equations. For example, Theodor Kaluza and Oskar Klein in the 1920s showed that Maxwell's equations could be derived by extending general relativity into five physical dimensions. This strategy of using additional dimensions to unify different forces remains an active area of research in physics.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Here it is noted that a quite different quantity, the magnetic polarization, μ0M by decision of an international IUPAP commission has been given the same name J. So for the electric current density, a name with small letters, j would be better. But even then the mathematicians would still use the large-letter name J for the corresponding current two-form (see below).

- ↑ Experiments like the Michelson–Morley experiment in 1887 showed that the "aether" moved at the same speed as Earth. While other experiments, such as measurements of the aberration of light from the stars, showed that the ether is moving relative to the Earth.

References

- 1 2 3 The story of electrical and magnetic measurements: from 500 B.C. to the 1940s, by Joseph F. Keithley, p115

- ↑ "The Dictionary of Scientific Biography", by Charles Coulston Gillispie

- ↑ Oliver Heaviside: the life, work, and times of an electrical genius of the Victorian age, Paul J. Nahin, JHU Press, isbn = 978-0-8018-6909-9, pages = 108–112

- ↑ The topological Foundations of Electromagnetism, Terence W. Barrett, World Scientific

- ↑ Crease, Robert. The Great Equations: Breakthroughs in Science from Pythagoras to Heisenberg, page 133 (2008).

- ↑ but are now universally known as Maxwell's equations. However, in 1940 Einstein referred to the equations as Maxwell's equations in "The Fundamentals of Theoretical Physics" published in the Washington periodical Science, May 24, 1940. Paul J. Nahin (2002-10-09). Oliver Heaviside: the life, work, and times of an electrical genius of the Victorian age. JHU Press. pp. 108–112. ISBN 978-0-8018-6909-9.

- ↑ Oliver J. Lodge (November 1888). "Sketch of the Electrical Papers in Section A, at the Recent Bath Meeting of the British Association". Electrical Engineer 7: 535.

- ↑ Jed Z. Buchwald (1994). The creation of scientific effects: Heinrich Hertz and electric waves. University of Chicago Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-226-07888-5.

- ↑ J. R. Lalanne, F. Carmona, and L. Servant (November 1999). Optical spectroscopies of electronic absorption. World Scientific. p. 8. ISBN 978-981-02-3861-2.

- ↑ Roger F. Harrington (2003-10-17). Introduction to Electromagnetic Engineering. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 49–56. ISBN 978-0-486-43241-0.

- ↑ page 480.

- ↑ http://www.mathematik.tu-darmstadt.de/~bruhn/Original-MAXWELL.htm

- ↑ "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". Fourmilab.ch. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||