History of rail transport in India

- This article is part of the history of rail transport by country series.

The history of rail transport in India began in the mid-nineteenth century.

Prior to 1850, there were no railway lines in the country. This changed with the first railway in 1853. Railways were gradually developed, for a short while by the British East India Company and subsequently by the Colonial British Government, primarily to transport troops for their numerous wars, and secondly to transport cotton for export to mills in UK. Transport of Indian passengers received little interest till 1947 when India got freedom and started to develop railways in a more judicious manner.[1]

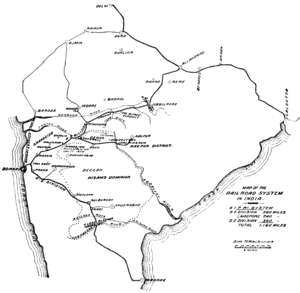

By 1929, there were 66,000 km (41,000 mi) of railway lines serving most of the districts in the country. At that point of time, the railways represented a capital value of some £687 million, and carried over 620 million passengers and approximately 90 million tons of goods a year.[2] The railways in India were a group of privately owned companies, mostly with British shareholders and whose profits invariably returned to Britain.[3] The military engineers of the East India Company, later of the British Indian Army, contributed to the birth and growth of the railways which gradually became the responsibility of civilian technocrats and engineers. However, construction and operation of rail transportation in the North West Frontier Province and in foreign nations during war or for military purposes was the responsibility of the military engineers.[2]

The linking of the Indian Railways

The first train in the country had run between Roorkee and Piran Kaliyar on December 22, 1851 to temporarily solve the then irrigation problems of farmers, large quantity of clay was required which was available in Piran Kaliyar area, 10 km away from Roorkee. The necessity to bring clay compelled the engineers to think of the possibility of running a train between the two points.[4] In 1845, along with Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, Hon. Jaganath Shunkerseth (known as Nana Shankarsheth) formed the Indian Railway Association. Eventually, the association was incorporated into the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, and Jeejeebhoy and Shankarsheth became the only two Indians among the ten directors of the GIP railways. As a director, Shankarsheth participated in the very first commercial train journey in India between Bombay and Thane on 16 April 1853 in a 14 carriage long train drawn by 3 locomotives named Sultan, Sindh and Sahib. It was around 21 miles in length and took approximately 45 minutes.

A British engineer, Robert Maitland Brereton, was responsible for the expansion of the railways from 1857 onwards. The Calcutta-Allahabad-Delhi line was completed by 1864. The Allahabad-Jabalpur branch line of the East Indian Railway opened in June 1867. Brereton was responsible for linking this with the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, resulting in a combined network of 6,400 km (4,000 mi). Hence it became possible to travel directly from Bombay to Calcutta via Allahabad. This route was officially opened on 7 March 1870 and it was part of the inspiration for French writer Jules Verne's book Around the World in Eighty Days. At the opening ceremony, the Viceroy Lord Mayo concluded that "it was thought desirable that, if possible, at the earliest possible moment, the whole country should be covered with a network of lines in a uniform system".[5]

By 1875, about £95 million (equal to £117 billion in 2012) were invested by British companies in Indian guaranteed railways.[6] It later transpired that there was heavy corruption in these investments, on the part of both, members of the British Colonial Government in India, and companies who supplied machinery and steel in Britain. This resulted in railway lines and equipment costing nearly double what they should have costed.[1]

By 1880 the network route was about 14,500 km (9,000 mi), mostly radiating inward from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. By 1895, India had started building its own locomotives and in 1896 sent engineers and locomotives to help build the Uganda Railways.

In 1900, the GIPR became a British government owned company. The network spread to the modern day states of Assam, Rajasthan, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh and soon various independent kingdoms began to have their own rail systems. In 1901, an early Railway Board was constituted, but the powers were formally invested under Lord Curzon. It served under the Department of Commerce and Industry and had a government railway official serving as chairman, and a railway manager from England and an agent of one of the company railways as the other two members. For the first time in its history, the Railways began to make a profit.

In 1907, almost all the rail companies were taken over by the government. The following year, the first electric locomotive made its appearance. With the arrival of World War I, the railways were used to meet the needs of the British outside India. With the end of the war, the railways were in a state of disrepair and collapse.

In 1920, with the network having expanded to 61,220 km, a need for central management was mooted by Sir William Acworth. Based on the East India Railway Committee chaired by Acworth, the government took over the management of the Railways and detached the finances of the Railways from other governmental revenues.

The growth of the rail network significantly decreased the impact of famine in India. According to Robin Burgess and Dave Donaldson, "the ability of rainfall shortages to cause famine disappeared almost completely after the arrival of railroads."[7]

Revenues

The period between 1920 and 1929 was a period of economic boom. Following the Great Depression, however, the company suffered economically for the next eight years. The Second World War severely crippled the railways. Trains were diverted to the Middle East and later, the Far East to combat the Japanese. Railway workshops were converted to ammunitions workshops and some tracks (such as Churchgate to Colaba in Bombay) were dismantled for use in war in other countries. By 1946 all rail systems had been taken over by the government.

Electrification

In 1904, the idea to electrify the railway network was proposed by W.H White, chief engineer of the then Bombay Presidency government. He proposed the electrification of the two Bombay-based companies, the Great Indian Peninsula Railway and the Bombay Baroda and Central India Railway (now known as CR and WR respectively).

Both the companies were in favour of the proposal. However, it took another year to obtain necessary permissions from the British government and to upgrade the railway infrastructure in Bombay city. The government of India appointed Mr Merz as a consultant to give an opinion on the electrification of railways. But Mr Merz resigned before making any concrete suggestions, except the replacement of the first Vasai bridge on the BB&CI by a stronger one.

Moreover, as the project was in the process of being executed, the First World War broke out and put the brakes on the project. The First World War placed heavy strain on the railway infrastructure in India. Railway production in the country was diverted to meet the needs of British forces outside India. By the end of the war, Indian Railways were in a state of dilapidation and disrepair.

By 1920, Mr Merz formed a consultancy firm of his own with a partner, Mr Maclellan. The government retained his firm for the railway electrification project. Plans were drawn up for rolling stock and electric infrastructure for Bombay-Poona/Igatpuri/Vasai and Madras Tambaram routes.

The secretary of state of India sanctioned these schemes in October 1920. All the inputs for the electrification, except power supply, were imported from various companies in England.

And similar to the running of the first ever railway train from Bombay to Thane on April 16, 1853, the first-ever electric train in India also ran from Bombay. The debut journey, however, was a shorter one. The first electric train ran between Bombay (Victoria Terminus) and Kurla, a distance of 16 km, on February 3, 1925 along the city’s harbour route.

The section was electrified on a 1,500 volts DC. The opening ceremony was performed by Sir Leslie Wilson, the governor of Bombay, at Victoria Terminus station in presence of a very large and distinguished gathering.

India's first electric locos (two of them), however, had already made their appearance on the Indian soil much earlier. They were delivered to the Mysore Gold Fields by Bagnalls (Stafford) with overhead electrical equipment by Siemens as early as 1910.

Various sections on the railway network were progressively electrified and commissioned between 1925 to 1930.

In 1956, the government decided to adopt 25kV AC single-phase traction as a standard for the Indian Railways to meet the challenge of the growing traffic. An organisation called the Main Line Electrification Project, which later became the Railway Electrification Project and still later the Central Organisation for Railway Electrification, was established. The first 25kV AC traction section in India is Burdwan-Mughalsarai via the Grand Chord.

Corruption in British Indian Railways

Sweeney (2015) Describes the large scale corruption that existed in the financing of British Indian railways, from its commencement in 1850s when tracks were being laid out and later in its operation.[8] The ruling colonial British government were too focussed on transporting goods for export to Britain, and hence did not use them to transport food instead to prevent famines such as the Great Bengal famines in 1905 and 1942. Indian economic development was never considered while deciding the rail network or places to be connected. It also resulted in the construction of many white elephants paid for by the natives, as commercial interests lobbied government officials with kickbacks. Government officials of the railways, especially ICS officials, and British nationals who participated in decision making such as James Mackay of Bengal were later rewarded after retirement with directorships in the City or the London headoffices and board rooms of these very so-called Indian railway companies, Poor resource allocation resulted in losses of hundreds of millions of pounds for Indians, including those in opportunity costs. Most shareholders of the railway companies set up were British. The head offices of most of these companies were in London, thus allowing Indian money to flow out of the country legally. Result, the railway debt made up nearly 50% of the Indian national debt from 1903 to 1945. Roberts and Minto spent large amounts trying to develop the Indian railways in the North west frontier province, resultign in large disproportionate losses. Guaranteed and subsidised companies were floated to run the railways, large guarantee payments were made despite there being a famine in Bengal. EIR, GIPR and Bombay Baroda (all operating in India and registered in London) had monopolies which generated profits, however these were never reinvested for the development of India.[9]

Start of Independent Indian Railways

Following independence in 1947, India inherited a decrepit rail network. About 40 per cent of the railway lines were in the newly created Pakistan. Many lines had to be rerouted through Indian territory and new lines had to be constructed to connect important cities such as Jammu. A total of 42 separate railway systems, including 32 lines owned by the former Indian princely states existed at the time of independence spanning a total of 55,000 km. These were amalgamated into the Indian Railways. Since then, independent India has more than quadrupled the length of railway lines in the country.

In 1952, it was decided to replace the existing rail networks by zones. A total of six zones came into being in 1952. As India developed its economy, almost all railway production units started to be built indigenously. The Railways began to electrify its lines to AC. On 6 September 2003 six further zones were made from existing zones for administration purpose and one more zone added in 2006. The Indian Railways has now sixteen zones.

In 1985, steam locomotives were phased out. In 1987, computerization of reservation first was carried out in Bombay and in 1989 the train numbers were standardised to four digits. In 1995, the entire railway reservation was computerised through the railway's internet. In 1998, the Konkan Railway was opened, spanning difficult terrain through the Western Ghats. In 1984 Kolkata became the first Indian city to get a metro rail system, followed by the Delhi Metro in 2002, Bangalore's Namma Metro in 2011, the Mumbai Metro and Mumbai Monorail in 2014 and Chennai Metro in 2015 . Many other Indian cities are currently planning urban rapid transit systems.

See also

References

- 1 2 Dalrymple, William (4 March 2015). "The East India Company: The original corporate raiders". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 Sandes, Lt Col E.W.C. (1935). The Military Engineer in India, Vol II. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ↑ "Postindependence: from dominance to decline". http://www.britannica.com/. Britanica Portal. Retrieved 24 June 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ http://www.thehindu.com/2002/08/10/stories/2002081000040800.htm

- ↑ R.P. Saxena, Indian Railway History Timeline

- ↑ British investment in Indian railway reaches £100m by 1875

- ↑ Burgess, Robin; Donaldson, Dave (2010). "Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Shocks? Evidence from India's Famine Era.". American Economic Review 100 (2): 453 in pages 449–53. doi:10.1257/aer.100.2.449. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Sweenety, Stuart (2015). Financing India's Imperial Railways, 1875–1914. London: Routledge. pp. 186–188. ISBN 1317323777.

- ↑ Tharoor, Shashi. "How a Debate Was Won in London Against British Colonisation of India". NDTV News. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

Bibliography

- Andrew, W. P. (1884). Indian Railways. London: W H Allen.

- Awasthi, A. (1994). History and Development of Railways in India. New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications.

- Bhandari, R.R. (2006). Indian railways : Glorious 150 Years (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Govt. of India. ISBN 8123012543.

- Ghosh, S. (2002). Railways in India – A Legend. Kolkata: Jogemaya Prokashani.

- Government of India Railway Board (1919). History of Indian Railways Constructed and In Progress corrected up to 31st March 1918. India: Government Central Press.

- Hurd, John; Kerr, Ian J. (2012). India's Railway History: A Research Handbook. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 2, South Asia, 27. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004230033.

- Huddleston, George (1906). History of the East Indian Railway. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co.

- Kerr, Ian J. (1995). Building the Railways of the Raj. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Kerr, Ian J. (2001). Railways in Modern India. Oxford in India Readings. New Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195648285.

- Kerr, Ian J. (2007). Engines of Change: the railroads that made India. Engines of Change series. Westport, Conn, USA: Praeger. ISBN 0275985644.

- Khosalā, Guradiāla Siṅgha (1988). A History of Indian Railways. New Delhi: Ministry of Railways, Railway Board, Government of India. OCLC 311273060.

- Law Commission (England and Wales) (2007) Consultation Paper: Indian Railways Repeal Proposals PDF (1.62 MiB)

- Rao, M.A. (1999). Indian Railways (3rd ed.). New Delhi: National Book Trust, India. ISBN 8123725892.

- Sahni, Jogendra Nath (1953). Indian Railways: One Hundred Years, 1853 to 1953. New Delhi: Ministry of Railways (Railway Board). OCLC 3153177.

- Satow, M. & Desmond R. (1980). Railways of the Raj. London: Scolar Press.

- South Indian Railway Co. (1900). Illustrated Guide to the South Indian Railway Company, Including the Mayavaram-Mutupet and Peralam-Karaikkal Railways. Madras: Higginbotham.

- — (1910). Illustrated Guide to the South Indian Railway Company. London.

- — (2004) [1926]. Illustrated Guide to the South Indian Railway Company. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1889-0.

- Vaidyanathan, K.R. (2003). 150 Glorious Years of Indian Railways. Mumbai: English Edition Publishers and Distributors (India). ISBN 8187853492.

- Westwood, J.N. (1974). Railways of India. Newton Abbot, Devon, UK; North Pomfret, Vt, USA: David & Charles. ISBN 071536295X.

External links

- "History of the Indian railways in chronological order". IRFC server. Indian Railways Fan Club. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- Roychoudhury, S. (2004). "A chronological history of India's railways". Retrieved 2007-10-21.

| ||||||||||||||