History of Cardiff

The history of Cardiff — a City and County Borough and the capital of Wales— spans at least 6,000 years. The area around Cardiff has been inhabited by modern humans since the Neolithic Period. Four Neolithic burial chambers stand within a radius of 10 mi (16 km) of Cardiff City Centre, with the St Lythans burial chamber the nearest, at about 4 mi (6.4 km) to the west. Bronze Age tumuli are at the summit of Garth Hill (The Garth; Welsh: Mynydd y Garth), within the county's northern boundary, and four Iron Age hillfort and enclosure sites have been identified within the City and County of Cardiff boundary, including Caerau Hillfort, an enclosed area of 5.1 ha (13 acres). Until the Roman conquest of Britain, Cardiff was part of the territory of an Iron Age Celtic British tribe called the Silures, which included the areas that would become known as Brecknockshire, Monmouthshire and Glamorgan. The Roman fort established by the River Taff, which gave its name to the city— Welsh: Caerdydd (Fort (Welsh: caer) and Taff (Welsh: daf, or dydd))— was built over an extensive settlement that had been established by the Silures in the 50s AD.

Origins

Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Central Europe began to migrate northwards from the end of the last ice age (between 12,000 and 10,000 years before present(BP)). The area that would become known as Wales had become free of glaciers by about 10,250 BP. At that time sea levels were much lower than today, and the shallower parts of what is now the North Sea were dry land. The east coast of present day England and the coasts of present day Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands were connected by the former landmass known as Doggerland, forming the British Peninsula on the European mainland. The post-glacial rise in sea level separated Wales and Ireland, forming the Irish Sea. Doggerland was submerged by the North Sea and, by 8000 BP, the British Peninsula had become the island of Great Britain.[1][2][3] John Davies has theorised that the story of Cantre'r Gwaelod's drowning and tales in the Mabinogion, of the waters between Wales and Ireland being narrower and shallower, may be distant folk memories of this time.[1]

As Great Britain became heavily wooded, movement between different areas was restricted, and travel between what was to become known as Wales and continental Europe became easier by sea, rather than by land. People came to Wales by boat from the Iberian Peninsula.[4] These Neolithic colonists integrated with the indigenous people, gradually changing their lifestyles from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering, to become farmers, some of whom settled in the area that would become Glamorgan.[5] They cleared the forests to establish pasture and to cultivate the land, developed new technologies such as ceramics and textile production, and they brought a tradition of long barrow construction that began in continental Europe during the 7th millennium BC.[2]

Archaeological evidence from sites in and around Cardiff—the St Lythans burial chamber, near Wenvoe (about 4 mi (6.4 km) west, southwest of Cardiff City Centre), the Tinkinswood burial chamber, near St. Nicholas, Vale of Glamorgan (about 6 mi (9.7 km) west of Cardiff City Centre), the Cae'rarfau Chambered Tomb, Creigiau (about 6 mi (9.7 km) northwest of Cardiff City Centre) and the Gwern y Cleppa Long Barrow, near Coedkernew, Newport (about 8.25 mi (13.28 km) northeast of Cardiff City Centre)—shows that these Neolithic people had settled in the area around Cardiff from at least around 6,000 BP, about 1500 years before either Stonehenge or The Egyptian Great Pyramid of Giza was completed.[6][7][8][9][10]

In common with the people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living around what is now known as Cardiff assimilated new immigrants and exchanged ideas of the Bronze Age and Iron Age Celtic cultures. Together with the approximate areas now known as Breconshire, Monmouthshire and the rest of Glamorgan, the area that would become known as Cardiff was settled by a Celtic British tribe called the Silures.[11] There is a group of five tumuli at the top of Mynydd y Garth—near the City and County of Cardiff's northern boundary—thought to be Bronze Age, one of which supports a trig. pillar on its flat top.[12][13] Several Iron Age sites have been found in the City and County of Cardiff. They are: the Castle Field Camp, east of Graig Llywn, Pontprennau; Craig y Parc enclosure, Pentyrch; Llwynda Ddu Hillfort, Pentyrch; and Caerau Hillfort—an enclosed area of 5.1 ha (13 acres).[14][15][16][17]

The Roman army invaded Great Britain in May 43 CE. The area to the south east of the Fosse Way—between modern day Lincoln and Exeter—was under Roman control by 47 CE. British tribes from beyond this new frontier of the Roman Empire resisted the Roman advance and the Silures, along with Caratacus (Welsh: Caradoc), attacked the Romans in 47 and 48 CE.[18] A Roman legion (thought to be the Twentieth) was defeated in 52 CE by the Silures.[18] Archaeological evidence shows that a settlement had been established by the Silures in central Cardiff in the 50s CE, probably during the period following their victory over the Roman army. The settlement included several large timber framed buildings of up to 45 m (148 ft) by 25 m (82 ft). The extent of the settlement is not known. Until the Romans established their fort, which they built on the earlier Silures settlement, the area that would become known as Cardiff remained outside the control of the Roman province of Britannia.[19]

The Roman settlement

.jpg)

Excavations from inside Cardiff Castle walls suggest Roman legions arrived in the area as early as the 54–68 AD during the reign of the Emperor Nero.[20] The Romans defeated the Silures and exiled Caratacus to Rome. They then established their first fort, built on this strategically important site where the River Taff and River Ely enter the Bristol Channel, on a 10 acres (4.0 ha) site on which were built timber barracks, stores and workshops.[20]

The Silures were not finally conquered until c. 75 AD, when Sextus Julius Frontinus' long campaign against them began to succeed, and they gained control of the whole of Wales.[1] The Roman fort at Cardiff was rebuilt smaller than before, in the 70s AD on the site of the extensive previous settlement dating from the 50s AD.[19] Another fort was built on the site around the year 250, with stone walls 10 ft (3.0 m) thick along with an earth bank, to help defend against attacks from Hibernia. This was used until the Roman army withdrew from the fort, and from the whole of the province of Britannia, near the start of the 5th century.[20][21]

The Viking settlement and the Middle Ages

During the early dark ages little is known of Cardiff. It is speculated that perhaps for long periods, raiders attacked the area, making Cardiff untenable,[20][22] The first written mention of Cardiff is made in the Annales Cambriae (The Welsh Annals) in 445.[23] By 850 the Vikings attacked the Welsh coast and used Cardiff as a base and later as a port. Street names such as Dumballs Road and Womanby Street come from the Vikings.[23]

In 1091, Robert Fitzhamon the Lord of Glamorgan, began work on the castle keep within the walls of the old Roman fort and by 1111, Cardiff town walls had also been built and this was recorded by Caradoc of Llancarfan in his book Brut y Tywysogion (English: Chronicle of the Princes).[24] Cardiff Castle has been at the heart of the city ever since.[25] Soon a little town grew up in the shadow of the castle, made up primarily of settlers from England.[26] Cardiff had a population of between 1,500 and 2,000 in the Middle Ages, a relatively normal size for a Welsh town in this period.[27] Robert Fitzhamon died in 1107,[20] later his daughter Mabel, married Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, the illegitimate son of King Henry I of England. He built the first stone keep in Cardiff Castle, and he used it to imprison Robert II, Duke of Normandy from 1126 until his death in 1134,[20] by order of King Henry I, who was the Duke's younger brother.[20] During the same period Ralph "Prepositus de Kardi" ("Provost of Cardiff") took up office as the first Mayor of Cardiff.[28] During this period after the Noman conquest they usually referred the leading figure by the Latin name of prepositus (English: provost) meaning "leading man".[29] Robert (Earl of Gloucester) died in 1147 and was succeeded by his son William, 2nd Earl of Gloucester who died without male heir in 1183.[20] The lordship of Cardiff then passed to Prince John, later King John through his marriage to Isabel, Countess of Gloucester, William's daughter. John divorced Isabel but retained the lordship until her second marriage; to Geoffrey FitzGeoffrey de Mandeville, 2nd Earl of Essex in 1214 until 1216 when the lordship passed to Gilbert de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford.[20]

Between 1158 and 1316 Cardiff was attacked on several occasions.[21] Amongst the various attackers of the castle were Ifor Bach, who captured the Earl of Gloucester who at the time held the castle. Morgan ap Maredudd apparently attacked the settlement during the revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294. In 1316 Llywelyn Bren, Ifor Bach's great-grandson, also attacked Cardiff Castle as part of a revolt. He was illegally executed in the town in 1318 on the order of Hugh Despenser the Younger.

By the end of the 13th century, Cardiff was the only town in Wales with a population exceeding 2,000, but it was relatively small compared to most other notable towns in the Kingdom of England.[30] Cardiff had an established port in the Middle Ages and by 1327, it was declared a Staple port.[21] The town had weekly markets and after 1340, Cardiff also had 2 annual fairs, which drew traders from all around Glamorgan.[31]

In 1404, Owain Glyndŵr burned Cardiff and took Cardiff Castle.[21] As the town was still very small, most of the buildings were made of wood and the town was reduced to ashes. However, the town was rebuilt not long after and began to flourish once again.[27]

County town of Glamorganshire

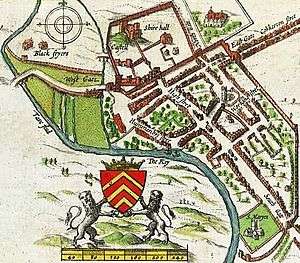

In 1536, the Act of Union between England and Wales led to the creation of the shire of Glamorgan. Cardiff was made the county town. Around this same time the Herbert family became the most powerful family in the area.[26] In 1538, Henry VIII closed the Dominican and Franciscan friaries in Cardiff, the remains of which were used as building materials.[27] A writer around this period described Cardiff: "The River Taff runs under the walls of his honours castle and from the north part of the town to the south part where there is a fair quay and a safe harbour for shipping." [27]

In 1542, Cardiff gained representation in the House of Commons for the first time. The next year, the English militia system was introduced. In 1551, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke was created first Baron Cardiff.[26]

Cardiff had become a Free Borough in 1542.[21] In 1573, it was made a head port for collection of customs duties. In 1581, Elizabeth I granted Cardiff its first royal charter.[26] By 1602 Pembrokeshire historian George Owen described Cardiff as "the fayrest towne in Wales yett not the welthiest.[26] The town gained a second Royal Charter in 1608.[32] During the Second English Civil War, St. Fagans just to the west of the town, played host to the Battle of St Fagans. The battle, between a Royalist rebellion and a New Model Army detachment, was a decisive victory for the Parliamentarians and allowed Oliver Cromwell to conquer Wales.[21] It is the last major battle to occur in Wales, with a total death toll of about 200 (mostly Royalist) soldiers killed.[26]

In the ensuing century Cardiff was at peace. In 1766, John Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute married into the Herbert family and was later created Baron Cardiff.[26] In 1778, he began renovations on Cardiff Castle.[33] In the 1790s, a race track, printing press, bank and coffee room all opened, and Cardiff gained a stagecoach service to London. Despite these improvements, Cardiff's position in the Welsh urban hierarchy had declined over the 18th century. Iolo Morganwg called it "an obscure and inconsiderable place", and the 1801 census found the population to be only 1,870, making Cardiff only the twenty-fifth largest town in Wales, well behind Merthyr Tydfil and Swansea.[34]

Building of the docks to modern Cardiff

In 1793, John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute was born. He would spend his life building the Cardiff docks and would later be called "the creator of modern Cardiff".[26] In 1815, a boat service between Cardiff and Bristol was established, running twice weekly.[33] In 1821, the Cardiff Gas Works was established.[33]

The town grew rapidly from the 1830s onwards, when the Marquess of Bute built a dock which eventually linked to the Taff Vale Railway. Cardiff became the main port for exports of coal from the Cynon, Rhondda, and Rhymney valleys, and grew at a rate of nearly 80% per decade between 1840 and 1870. Much of the growth was due to migration from within and outside Wales: in 1851, a quarter of Cardiff's population were English-born and more than 10% had been born in Ireland. By the 1881 census, Cardiff had overtaken both Merthyr and Swansea to become the largest town in Wales. Cardiff's new status as the premier town in South Wales was confirmed when it was chosen as the site of the University College South Wales and Monmouthshire in 1893.[34]

Cardiff faced a challenge in the 1880s when David Davies of Llandinam and the Barry Railway Company promoted the development of rival docks at Barry. Barry docks had the advantage of being accessible in all tides, and David Davies claimed that his venture would cause "grass to grow in the streets of Cardiff". From 1901 coal exports from Barry surpassed those from Cardiff, but the administration of the coal trade remained centred on Cardiff, in particular its Coal Exchange, where the price of coal on the British market was determined and the first million-pound deal was struck in 1907.[34] The city also strengthened its industrial base with the decision of Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds, owners of the Dowlais Ironworks in Merthyr, to build a new steelworks close to the docks at East Moors in 1890. The metalworks at nearby Port Talbot also helped developed the industrial base of Glamorgan.

City and capital city status

King Edward VII granted Cardiff city status on 28 October 1905,[35] and the city acquired a Roman Catholic Cathedral in 1916.[36] In subsequent years an increasing number of national institutions were located in the city, including the National Museum of Wales, Welsh national war memorial, and the University of Wales registry - although it was denied the National Library of Wales, partly because the library's founder, Sir John Williams, considered Cardiff to have "a non-Welsh population".[37]

After a brief post-war boom, Cardiff docks entered a prolonged decline in the interwar period. By 1936, their trade was less than half its value in 1913, reflecting the slump in demand for Welsh coal.[37] Bomb damage in during the Cardiff Blitz in World War II included the devastation of Llandaff Cathedral, and in the immediate postwar years the city's link with the Bute family came to an end.

The city was proclaimed capital city of Wales on 20 December 1955, by a written reply by the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George. Caernarfon had also vied for this title.[38] Cardiff therefore celebrated two important anniversaries in 2005. The Encyclopedia of Wales notes that the decision to recognise the city as the capital of Wales "had more to do with the fact that it contained marginal Conservative constituencies than any reasoned view of what functions a Welsh capital should have". Although the city hosted the Commonwealth Games in 1958, Cardiff only became a centre of national administration with the establishment of the Welsh Office in 1964, which later prompted the creation of various other public bodies such as the Arts Council of Wales and the Welsh Development Agency, most of which were headquartered in Cardiff.

The East Moors Steelworks closed in 1978 and Cardiff lost population during the 1980s,[39] consistent with a wider pattern of counter urbanization in Britain. However, it recovered and was one of the few cities (outside London) where population grew during the 1990s.[40] During this period the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was promoting the redevelopment of south Cardiff; an evaluation of the regeneration of Cardiff Bay published in 2004 concluded that the project had "reinforced the competitive position of Cardiff" and "contributed to a massive improvement in the quality of the built environment", although it had failed "to attract the major inward investors originally anticipated".[41]

In the 1999 devolution referendum, Cardiff voters rejected the establishment of the National Assembly for Wales by 55.4% to 44.2% on a 47% turnout, which Denis Balsom partly ascribed to a general preference in Cardiff and some other parts of Wales for a 'British' rather than exclusively 'Welsh' identity.[42][43] The relative lack of support for the Assembly locally, and difficulties between the Welsh Office and Cardiff Council in acquiring the original preferred venue, Cardiff City Hall,[44] encouraged other local authorities to bid to house the Assembly.[45] However, the Assembly eventually located at Crickhowell House in Cardiff Bay in 1999; in 2005, a new debating chamber on an adjacent site, designed by Richard Rogers, was opened.

The city was county town of Glamorgan until the council reorganisation in 1974 paired Cardiff and the now Vale of Glamorgan together as the new county of South Glamorgan. Further local government restructuring in 1996 resulted in Cardiff city's district council becoming a unitary authority, the City and County of Cardiff, with the addition of Creigiau and Pentyrch.

On 1 March 2004, Cardiff was granted Fairtrade City status.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 4 & 5. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- 1 2 Morgan (Ed), Prys (2001). History of Wales, 25,000 BC AD 2000. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. pp. 17–22. ISBN 0-7524-1983-8.

- ↑ "Overview: From Neolithic to Bronze Age, 8000–800 BC (Page 1 of 6)". BBC History website. BBC. 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "Genes link Celts to Basques". BBC News website (BBC). 2001-04-03. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "GGAT 72 Overviews" (PDF). A Report for Cadw by Edith Evans BA PhD MIFA and Richard Lewis BA. Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust. 2003. pp. 7, 31 & 47. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "St Lythans Chambered Long Cairn, Maesyfelin; Gwal-y-Filiast, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "TINKINSWOOD CHAMBERED CAIRN, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2003-01-29. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "CAE-YR-ARFAU; CAE'RARFAU BURIAL CHAMBER, site details, Coflein". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "GWERN-Y-CLEPPA, LONG BARROW, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2003-02-10. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "Your guide to Stonehenge, the World's Favourite Megalithic Stone Circle". Stonehenge.co.uk website. Longplayer SRS Ltd (trading as www.stonehenge.co.uk). 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 15 18. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- ↑ "GARTH HILL, BARROW I". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ "Trig point on Tumulus on Garth Hill". Geograph British Isles website. Geograph British Isles. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ "CASTLE FIELD CAMP E OF CRAIG-LLYWN, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "CRAIG-Y-PARC, ENCLOSURE, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 1990. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "LLWYNDA-DDU, HILLFORT, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 1989-06-14. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "CAERAU HILLFORT, site details". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2003-02-05. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- 1 2 Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 27 29. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- 1 2 "CARDIFF ROMAN SETTLEMENT - Site details - coflein". RCAHMW website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monumentss of Wales. 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Romans 55-400AD". Cardiff Castle. Archived from the original on 2008-03-04. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A Cardiff & Vale of Glamorgan Chronology up to 1699". Bob Sanders. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "Cardiff". www.1911encyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- 1 2 "Chronology of Cardiff History". Theosophical Society. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "The Town's Wall". Herbert E. Roese. 2000-02-06. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- ↑ "Cardiff history". Visit Cardiff. Archived from the original on 2008-02-08. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Cardiff Timeline". Cardiffians. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "A SHORT HISTORY OF CARDIFF". Tim Lambert. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "The Early Mayors of Cardiff". Cardiff Council. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ↑ "Medieval English Towns - Glossary". Medieval English Towns. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ "Benchmarking medieval economic development: England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, circa 1290" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ "A Short History of Cardiff". World History Encyclopedia by Tim Lambert. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ "A History Lovers Guide to Cardiff". GoogoBits.com. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- 1 2 3 "A Cardiff & Vale of Glamorgan Chronology 1700 - 1849". Bob Sanders. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- 1 2 3 The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 27849. p. 7249. October 31, 1905. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ↑ The ancient Llandaff Cathedral was outside the city boundaries until 1922

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of Wales

- ↑ Cardiff as Capital of Wales: Formal Recognition by Government. The Times. 21 December 1955.

- ↑ Cardiff Wales through time | Population Statistics | Total Population

- ↑ http://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/cbcb/census1.pdf

- ↑ Esys Consulting Ltd, Evaluation of Regeneration in Cardiff Bay. A report for the Welsh Assembly Government, December 2004

- ↑ Balsom, Denis. 'The referendum result'. In Jones, James Barry; Balsom, Denis (ed.), The road to the National Assembly for Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2000.

- ↑ http://www.swansea.ac.uk/history/research/Wales%20the%20Postnation.pdf

- ↑ "Where to now for the Welsh Assembly?". BBC News. 1997-11-25. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ http://ossw.wales.gov.uk/2006/foi/foi_20060920_15.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Cardiff. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||