Historic West Adams

Historic West Adams is a Los Angeles, California, residential and commercial area along the route of the Rosa Parks Freeway, paralleling the east-west Adams Boulevard. With variously described boundaries, the area was an exclusive residential district In the late 19th and early 20th centuries for many wealthy and influential people. It underwent a period of deterioration, but many of its stately old buildings have been and are being rehabilitated and preserved. The constituent neighborhoods have a wide range of income levels and lifestyles.

Geography

Boundaries

Although there are no official boundaries for Historic West Adams, it is marked by signs on the Interstate 10 Freeway that inform the motorist "Historic West Adams Next Six Exits."[1]

Automobile Club

The Automobile Club of Southern California delineates no boundaries for the area, but centers it south of the Rosa Parks Freeway on the West Adams Alternative School, which lies between Seventh and Fourth avenues (west and east) and Adams Boulevard and 25th Street (north and south).[2]

Mapping L.A.

Mapping L.A. project leader Doug Smith of the Los Angeles Times reported that, in response by the public to advance posting of the proposed maps, "Among the bitter rifts we encountered were the competing claims to the name West Adams."[3]

Historical purists would reserve the designation West Adams for the once-upper-crust district of Victorian mansions now falling in the shadow of USC. But residents farther west have appropriated the name for that hard-to-define area between the 10 Freeway and Baldwin Hills. To bolster their case, the area's Neighborhood Empowerment Zone bears that name. The discussion has taken on powerful emotional content in recent years as part of a larger debate over gentrification and changing demographics in that part of the city. We resolved the argument as best we could, using the West Adams label for the region west of Crenshaw Boulevard and including the old mansions east of Vermont Avenue as part of University Park.[3]

The Mapping L.A. project displays eight neighborhoods, north and south of the Rosa Parks Freeway and listed west to east below:

North of the freeway: Mid-City between Robertson Boulevard or La Cienega Boulevard and Crenshaw Boulevard;[4] Arlington Heights, between Crenshaw and Gramercy Place;[5] Harvard Heights, between Gramercy Place and Normandie Avenue, and Pico-Union, between Normandie Avenue and the Harbor Freeway.[6]

South of the freeway: West Adams, between Culver City and Crenshaw Boulevard; Jefferson Park, between Crenshaw Boulevard and Western and Arlingrton avenues; Adams-Normandie; between Western and Vermont Avenue, and University Park, between Vermont Avenue and the Harbor Freeway.[7]

West Adams Heritage Association

The West Adams Heritage Association states that West Adams stretches "roughly from Figueroa Street on the east to West Boulevard on the west, and from Pico Boulevard on the north to Jefferson Boulevard on the south."[8]

Major neighborhoods

Click to see articles on each one. The boundaries are those of Mapping L.A.

Other areas

Glen Airy

Glen Airy was a residential subdivision, sales for which were active in 1911 and 1912.[9][10][11] Streets included in the subdivision were variously described as 30th Avenue from 21st Street to West Adams Street and 28th and 29th avenues from 21st Street to West Adams (1924),[12] West Adams Street at the corner of Longwood Avenue[13] and "the western end of West Adams street."[14] An official subdivision map gives the boundaries as Adams Street on the north, roughly Mansfield Avenue on the east, Roseland Street on the south and the rear line of properties fronting on Edgewater Street on the west, with part of the tract being in the city and part outside of it.[15]

Kinney Heights

Kinney Heights was developed around 1900 by developer Abbott Kinney, for whom it is named. It was a suburban tract of large Craftsman style homes at what was then the western edge of Los Angeles. The homes featured amenities like "beveled-glass china cabinets, marble fireplaces and mahogany floors".[16] It was accessible to downtown via streetcar and attracted upper-middle-class families.[17]

Many of the hundred-year-old homes are still standing and have been renovated and upgraded. The neighborhood is part of the West Adams Terrace Historic Preservation Overlay Zone (HPOZ).[18]

Twentieth Street Historic District

The Twentieth Street Historic District consists of a row of bungalows and Craftsman-style houses in the 900 block on the south side of 20th Street.

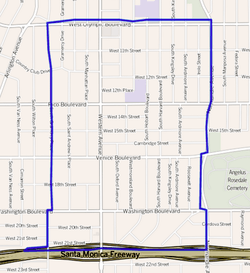

Western Heights

Western Heights, bounded by Washington Boulevard on the south, Arlington Avenue on the west, the Rosa Parks Freeway on the north and Western Avenue on the east, began in 1903 or 1904 with the building of a single cottage, according to local historian Don Lynch. The neighborhood later attracted wealthy professionals and summer visitors from the Midwest and East, and in 2007 it counted 107 single-family houses.[19] Two of them are:

- Jonas B. Kissam residence on West 20th Street, a three-story Craftsman built in 1907.[19]

- Ten-room Hugh Asher home, with a carriage house, built in 1904 on South Gramercy Place.[19] In 1975 singer Marvin Kaye deeded it to his parents. In April 1984 Gaye's father shot him to death there as Gaye defended his mother against an assault by her husband.[20]

Notable places

- Automobile Club of Southern California headquarters, 1923 (southwest corner of Adams Boulevard and Figueroa Street)

- Felix Chevrolet (northeast corner of Jefferson Boulevard and Figueroa)

- Forthmann House - At 1102 W. 28th Street, a Victorian home built in 1880. This home is known as the Forthmann House and was built for the founders of the Los Angeles Soap Co. It is characterized by its mansard-roofed tower.

- John B. Kane Residence (Bonsallo Avenue near 23rd St)

- John Tracy Clinic (Adams just east of Hoover Street)

- Mount St. Mary's College, Doheny Campus (Adams just east of Hoover Street)

- Olympic Village, 1932 Summer Olympics (near intersection of Adams and Hoover)

- Second Church of Christ, Scientist - At 948 West Adams Blvd, this 1910 building, designed in the Classical Revival style by Alfred H. Rosenheim and used as a Christian Science church for almost 100 years, will be restored and used as a community center by the Art of Living Foundation Los Angeles Center

- St. John's Cathedral (southwest corner of Adams and Figueroa)

- St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Roman Catholic church (northwest corner of Adams and Figueroa)

- William Andrews Clark Memorial Library

History

Founding and early days

West Adams is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Los Angeles, with most of its buildings erected between 1880 and 1925, including the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. West Adams was developed by railroad magnate Henry E. Huntington and wealthy industrialist Hulett C. Merritt of Pasadena. It was once the wealthiest district in the city, with its Victorian mansions and sturdy Craftsman bungalows home to Downtown businessmen and professors and academicians at the University of Southern California.

The neighborhood was the site of the "fashionable" Marlborough School (Los Angeles), founded in the redecorated rooms of the former Marlborough Hotel on West 23rd Street by Mrs. George A. Caswell in 1890; in 1916 the school moved to a new home on West Third Street.[21][22][23][24][25]

As early as 1906 the area was referred to as "exclusive"[26] and in 1913 as a "fashionable residence district."[27] In 1916 the district was known for its "private parks and handsome homes," and the boulevard itself was undergoing improvements that would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. The Los Angeles Times predicted "there will be no more splendid boulevard in America." Between Figueroa and Hoover streets the old paving was torn out and an asphalt surface was lain, making the street 65 feet wide. In the middle were installed a series of islands that were planted with flowers, shrubs and mature palms. Many trees were set out in the "parkings," or parkways, along the street." "Lofty" electroliers, or street lamps, were installed; they were the same design as those on Lake Front Drive in Chicago.[28]

In 1909 the sidewalks of St. James Park were known as a place where nurses attending perambulators would air and care for babies of the mothers who lived nearby.[29]

The Great Depression of the 1930s struck the neighborhood, and a West Adams District Unemployment Relief Committee was organized in February 1931. "Under a competent foreman[,] the men will go from house to house in the district and perform odd jobs in homes, yards and vacant lots calculated to beautify, such as cleaning, painting, repairing and painting." The team would be selected "from the ranks of married men with families who live in the district and who are registered voters." The pay was to be $2 a day for five hours' work from a fund solicited from residents of an area bounded by West Adams Street, Venice Boulevard, Harvard Boulevard and 7th Avenue.[30]

Development and construction

Buildings

Historic West Adams[31] is home to one of the largest collections of notable old houses west of the Mississippi River. The West Adams area was developed between 1880 and 1925 and contains many diverse architectural styles of the era, including the Queen Anne, Shingle, Gothic Revival, Transitional Arts and Crafts, American Craftsman/Ultimate Bungalow, Craftsman Bungalow, Colonial Revival, Renaissance Revival, Mediterranean Revival, Spanish Colonial Revival, Mission Revival, Egyptian Revival, Beaux-Arts and Neoclassical styles. West Adams boasts the only existing Greene and Greene house left in Los Angeles. Its historic homes are frequently used as locations for movies and TV shows including CSI, Six Feet Under, The Shield, Monk, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and Of Mice and Men. Singer Ray Charles's business headquarters, including his RPM studio, is located at 2107 Washington Boulevard.

The intersection of Washington Boulevard and Westmoreland Boulevard, at the studio, is named "Ray Charles Square" in his honor.

1905. West Adams Terrace, which in 2003 became a Los Angeles historic preservation overlay zone, was platted in 1905 from what had been called the Bauer tract. This area on the north side of Adams west of Western Avenue fell under the control of a syndicate headed by William Miles, president, and Charles McKenzie, H.R. Callender, S.J. White and C.G. Andrews. Said to be "the last piece of available elevated land [with] a magnificent view of the valley and surrounding foothills," it was divided into 235 lots with building restrictions ranging from $2,500 to $3,000.[32]

1906. "The growing popularity of apartment houses is causing them to encroach on grounds heretofore exclusively reserved for high-class residences," a Los Angeles Times reporter wrote in September 1906. He was reporting on "one of the handsomest apartment-houses in the city," which was designed by Thornton Fitzhue and was to be built on the southern side of St. James Park, "with a north frontage on the botanical gardens." All would have servants' quarters.[33] Landowner John R. Powers completed another apartment building in St. James Place in 1909, with an entrance also on Scarff Street. Designed by George W. Wryman, it was divided into four apartments of seven rooms each; the venture represented an investment of $35,000.[34]

1921. On June 26, 1921, the Automobile Club of Southern California announced it would build a new home on a site purchased the year before on the southwest corner of Figueroa and Adams streets. It was to be of Spanish architecture and would feature an octagonal domed lobby extending up three floors. Locker rooms and showers were planned for both men and women. The third floor would contain a dining room, with kitchens, a men's lounge and smoking room, a large assembly room and a directors room. Sumner Hunt and S.R. Burns were the architects and Aurele Vermeulen the landscape architect.[35]

1924. Ground was broken on September 28, 1924, for the Church of the Advent, Episcopal, on the corner of Longwood Avenue in the Glen Airy district at the end of the West Adams streetcar line, with Bishop J.H. Johnson present. The brick structure with heavy wooden beams was to replace a temporary structure. Plans called for a parish house at the rear of the lot.[36]

1989. Construction began on the West Adams Foursquare Church, 2614 South LaBrea Avenue, after six hundred people joined in a groundbreaking ceremony in August 1989.[37]

Myron Hunt

1990-91. An 82-year-old Mediterranean Revival house at 3320 West Adams Boulevard, Jefferson Park, became the center of attention in 1990 and 1991 when members of the West Adams Historical Association, or WAHA, strove to protect and rehabilitate it over the equally strong (and eventually successful) desire of the predominantly black Holman United Methodist Church to tear it down as part of its plan to build a modern campus. The pastor, James M. Lawson, wrote in his church bulletin that "WAHA is a white organized and led organization. They are largely the sons and daughters of the generation which did not want ethnic people in this area, formed housing covenants to keep us out, burned KKK-type crosses to scare us away and then fled as we continued to buy housing to suit ourselves." He later said that his language was symbolic, not literal, but that nevertheless the WAHA preservation agenda represented a subtle form of racism. Though the house, designed by architect Myron Hunt, was registered as a state historical resource, it was eventually demolished.[38]

1992. Ward Villas, a gated apartment complex for low-income seniors, opened at 1177 West Adams Boulevard west of Hoover Street under the auspices of a nonprofit corporation formed by the Ward African Methodist Episcopal Church with funds from both public and private sources. Civil rights icon Rosa Parks was the guest of honor.[39][40]

2004-2007. A century-old neighborhood of houses and businesses was demolished at Vermont Avenue and Washington Boulevard to make room for a new high school.[41] Built at a cost of $176 million, West Adams High School opened at 1500 West Washington Boulevard with an all-weather football field and track, a weight room, fitness cener, swimming pool, two gymnasiums and lighted baeball and softball diamonds.[42][43]

Freeways

In the 1950s, the construction of the Harbor Freeway destroyed many large homes on the east side of West Adams, while the 1960s construction of the Santa Monica Freeway took half of Berkeley Square, which held significant houses designed by Elmer Grey, and bisected West Adams Heights. Most of the other half of Berkeley Square was taken by an expansion of 24th Street Elementary School.[44]

Infrastructure

1906. A report was made in 1906 that the West Adams district lacked water, with one resident complaining in late July that "the only toilet facility enjoyed by himself and family . . . was supplied by the drippings from a faucet into a pitcher." City water officials said that West Adams was supplied by a 30-inch main that ran down Hoover Street from the Bellevue Reservoir[45] and that work was under way to remedy the situation by bringing more water from the "much higher" Ivanhoe reservoir, which was under construction in today's Silver Lake community and which would store "practically a billion gallons.*[26]

1925. A landmark decision was handed down by the California Supreme Court on February 27, 1925, wherein the court decided that it was legal for cities to establish zoning that limited the kind of housing that could be erected in any given restricted area. Property developer George Lee Miller had proposed building a four-family flat at 3802 West Adams Street, but the city denied permission because it was considering adopting a comprehension zoning plan that would forbid building flats in that area. A trial court ruled in the city's favor, but an appellate court rejected that decision.[46] The city appealed, and the state's highest court unanimously decided that

[J]ustification for residential zoning may, in the last analysis, be rested upon the protection of the civic and social values of the American home. The establishment of such districts is for the general welfare because it tends to promote and perpetuate the American home. It is axiomatic that the welfare, and indeed the very existence of a nation depends upon the character and caliber of its citizenry. . . . It is a matter of common knowledge that a zoning plan of the extent contemplated in the instant case cannot be made in a day. Therefore, we may take judicial notice of the fact that it will take much time to work out the details of such a plan and that obviously it would be destructive of the plan if, during the period of its incubation, parties seeking to evade the operation thereof should be permitted to enter upon a course of construction which might progress so far as to defeat in whole or in part the ultimate execution of the plan.[47]

1926. In July 1926, West Adams property owners held a mass meeting in the Glen Airy schoolhouse[48] to protest against the high cost of a storm drain project on the street and to draw up a petition against the "intolerable injustice,' which they presented to the City Council. It was said that Peter R. Gadd, the contractor, had increased the tab by billing $204,145 for "extras," which amounted to more than the original proposed cost of the contract.[49] Later the city estimated the overcharge at $298,981 and refused to help Gadd to collect the money from property owners. The California Supreme Court ruled in the city's favor.[50]

1990. The city's "Fair Share" policy regarding distribution of federal anti-poverty funds came under attack in April 1990, when the Los Angeles Times published an article that began: "Watts and West Adams are two strikingly different neighborhoods, separated by a few miles of freeway, but in human terms by a yawning gap in family income, property values and upward mobility." The article stated that West Adams, with a population of 30,500, had an average household income of $22,500 and unemployment of 18 percent and that the figures for Watts, with a population of 30,748, were $16,100 and 44 percent, yet anti-poverty funds were being distributed unequally to projects in West Adams.[51]

Recognition

Historic West Adams was awarded the "Neighborhood of the Year" award for 2015 by the Curbed L.A. news and feature website.[52]

More than 70 sites in Historic West Adams have received recognition as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument, a California Historical Landmark, or listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Several areas of Historic West Adams, namely, Harvard Heights, Lafayette Square, Pico-Union, and West Adams Terrace, were designated as Historic Preservation Overlay Zones by the city of Los Angeles, in recognition of their outstanding architectural heritage. Menlo Avenue-West Twenty-ninth Street Historic District, North University Park Historic District, Twentieth Street Historic District, Van Buren Place Historic District and St. James Park Historic District, all with houses of architectural significance, are located in this area.

Population changes

Paul Williams

The development of the West Side, Beverly Hills and Hollywood, beginning in the 1910s, siphoned away much of West Adams' upper-class white population; upper-class blacks began to move in around this time, although the district was off limits to all but the very wealthiest African-Americans. One symbol of the area's emergence as a center of black wealth at this time is the 1949 headquarters of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, a late-period Moderne structure at Adams and Western designed by renowned black architect Paul Williams. It housed what was once one of the nation's largest black-owned insurers (currently, along with an adjacent new building, it is now a campus for a large non-profit). West Adams' transformation into an affluent black area was sped by the Supreme Court's 1948 invalidation of segregationist covenants on property ownership.[53] Many of the Historic West Adams neighborhoods are experiencing a renaissance of sorts with their stunning houses being restored to their previous elegance.[53]

On December 6, 1945, Superior Court Judge Thurmond Clark dismissed the suit of eight white property owners who tried to force fifty African-American occupants (250 residents) from an area bounded by La Salle Avenue, Washington Boulevard, Western Avenue and Adams Boulevard, contending that the defendants had violated property restrictions against blacks agreed on by white property owners eight years previously. The defendants, who included actress Hattie McDaniels and singer Ethel Waters, replied that the original subdivision restrictions had expired and that more than half of the area was then owned by black people. Clark decided that no testimony would be taken in the case, and he wrote that "it is time that members of the Negro race are accorded, without reservations and evasions, the full rights guaranteed to them" under the Federal Constitution.[54][55]

In 1985 the neighborhoods were becoming changed by a "wave of younger couples and families,",[56] and by the next year, Historic West Adams had become "a predominantly black middle-class area with growing Latino and Korean segments, plus a mix of Hungarians, Poles, Japanese, USC students and an increasing young professional and gay population."[57] In that year, though, tensions erupted between some of the newcomers and the older, more settled black residents. It got so bad that a petition was presented against plans by the West Adams Heritage Association to close off 20th Street for its annual Historic Homes and Street Faire, which drew upwards of a thousand visitors to the neighborhood. After a heated public hearing, the city's Board of Public Works denied a permit for the festivity.[58]

Mirroring changes seen throughout Los Angeles, the district's Latino population has been growing. The area's architecture and proximity to USC have brought some upper-middle-class whites as well. Many African-American gays have moved into the neighborhood, and it has become the center of black gay life in Los Angeles, even earning the nickname of "the black West Hollywood" or "the black Silver Lake"[59] In June 1994, though, heavy damage was done to the home of one gay couple, Bob Bowerman and Penn Barrosse, who had lived in the neighborhood for a decade and spent a million dollars fixing up their 21-room, three-story house. Bowerman said he considered intrusion by culprits who spray-painted their home to be a hate crime.[60]

Crimes and disturbances

1896. St. James Park fire

A night-time fire destroyed a tent displaying phonograph machines and harboring items from other exhibits during a festive St. James Park carnival in June 1896. Two workers were burned when they tore away tent flaps to halt the spread of the blaze. Earlier, "the tamale booth, which was one of the most beautiful in the grounds," was also ablaze, but it was smothered by "two plucky women with brooms."[61] The event had a "gypsy" carnival theme, with "myriads of electric lights," palmists, fortune tellers and people in costume. Outside was "a burly negro bouncer, clad in all the colors of the rainbow, calling in stentorian tones attention to the attractions within." Profits went to the Stimson-Lafayette Industrial School.[62]

1916. Security officer killing

John S. Hendrickson, head of a private security firm, was killed by pistol fire on January 24, 1916, when he challenged two men skulking about the neighborhood some fifty feet west of the Chester Place entrance on West Adams Street.[63]

1924-1927. Peat fire

| “ | [T]he atmosphere for eight or ten feet above the surface [dances] with heat waves as though over a bed of hot ashes. . . . The smell of the hot air is suffocating. | ” |

| — Newspaper reporter[64] | ||

For three years between 1924 and 1927, a smoldering peat fire on the Elias Jackson "Lucky" Baldwin estate near the Baldwin Hills, between Jefferson and Hauser streets, adversely affected the air quality of the West Adams district, spreading to affect twelve acres. The stench even drifted into Culver City, where windows had to be shut in schoolhouses because of the nuisance. Four teenagers were among those severely burned while crossing the bog. Civil suits for damages were brought against the land owners and, after some weeks of discussion, the City Council allocated funds for city firemen to quench the nuisance, hoping to recoup the cost later.[65][66][67][68][69][70]

In the meantime, the city filed charges of maintaining a public nuisance against three men affiliated with the Baldwin estate or with the care of the property. After a bench trial in which the defense stated that the fire could have been burning "for many centuries," Municipal Judge William Frederickson ruled against the city, stating that "fires there as elsewhere in the neighborhood are what might be considered a common enemy and the municipal authorities should put out the fire, if possible, by the use of a water system or other means."[71] The City Council attempted to bill Anita Baldwin, owner of the property, for the cost of quenching the embers,[72] but City Attorney Jess E. Stephens ruled that the city had no authority to do so.[73]

1924-1941. May and Nina Martin

| “ | Although I believe that in all probability Stone was the one who committed the crime, there is just enough doubt to preclude the hanging of a man solely upon circumstantial evidence supported almost wholly by two witnesses of very doubtful credibility. | ” |

| — Governor C.C. Young[64] | ||

West Adams was rivened in 1924 when two sisters, May Martin, 12, and Nina Martin, 8, disappeared on August 23 while away from their home at 2854 Mansfield Street (now Avenue) in a district then known as Glen Airy. Screams had been heard from the direction of the La Brea slough, which was thoroughly searched by.relatives, friends, Boy Scouts and police from the University division of the Los Angeles Police Department, to no avail.[74] On September 7, a mass meeting was held at the Calvary Methodist Church, Adams and Cloverdale Avenue, where police and sheriff's deputies were scored because of asserted "lack of interest" in the case and a motion was unanimously adopted asking for more effort to find the girls. The motion was sent on to the congregations of Angelus Temple, Temple Auditorium, Trinity Methodist Church and other "various churches in the West Adams district."[75]

Investigators questioned just about all the residents of the immediate West Adams area, and on September 16, 1924, some 275 police officers and 17 mounted patrolmen hunted for the girls' bodies in the rugged Baldwin Hills (mountain range) and nearby marshlands. The searchers were unsuccessful that day,[76] but on February 4 the two bodies were discovered by an agricultural worker in a shallow grave. Even The New York Times reported the news.[77]

Scott C. Stone, who was a familiar person in the neighborhood because of his employment by a private watch patrol, was convicted of the crime on December 11, 1926, and was sentenced to death. Because he was convicted on circumstantial evidence and steadfastly maintained his innocence, petitions asking clemency were sent to Governor C.C. Young by church organizations, some of the girls' relatives, including their mother, Mrs. Paul Buus, by police officers and even by some members of the jury, and on March 9, 1927, Young announced that there were doubts about the case: he commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. After sixteen years in prison, Stone was released on parole in February 1941.[78][79][80]

1927. Prohibition

Patrolman O.J. King smelled the odor of fermenting liquor while walking by a luxurious 14-room mansion at 2234 West Adams in September 1927, and soon a squad of policemen raided the swanky house to find that the place had been converted into a distillery. There were several thousand gallons of liquor stored in various rooms, and pipes had been let down from the second floor to the furnace and a 350-gallon still. Ninety 50-gallon barrels of mashed were stored in each of the rooms on the second floor. Occupants were arrested on suspicion of violating prohibition laws.[81]

1957-present. Prostitution, drugs and gangs

Gang activity and tagging have been evident in some parts of Historic West Adams.[82][83] In May 1957 Police Captain C.R. Swan of the University Division condemned area businesses like cafes and bars for allowing prostitutes to work from there.[84] In 1960 a delegation led by real estate dealer Cecil Murrell of 4737 Angeles Vista Boulevard, head of the area's Council of Organizations Against Vice, laid a complaint before the Los Angeles City Council that "flagrant prostitution" was endemic in West Adams and other South Los Angeles areas and that women charged with the offense were often back on the streets after serving minimum sentences. A community meeting was scheduled later at 1909 West Adams Boulevard to talk about the matter.[85][86][87] A.S. (Doc) Young, editor of the black-oriented Los Angeles Sentinel, complained in a column about "hordes of Caucasian motorists who, apparently, have been led to believe that certain Negro areas are wide open red-light districts," or centers of prostitution. A Sentinel survey found streetside solicitation in the West Adams district on Western Avenue at 27th and 28th streets.[88]

In 1965 the Los Angeles Times printed a map with West Adams Boulevard, Western Avenue south to 69th Street and Vermont Avenue south to Jefferson Boulevard shaded under the headlines "Vice Casts Its Shadow on West Adams District: White Men on Prowl for Negro Streetwalkers."[87] Reporter Paul Coates wrote:

. . . the housewives, mothers, schoolgirls, young businesswomen who live and work in the once quite fashionable, still quite comfortable West Adams district . . . are . . . ashamed to walk down the street. They cannot leave their homes, day or night, without running the risk of being accosted by a white man on the prowl for a Negro prostitute. The area of well-kept homes on either side of Western Ave. and its many attractive business establishments is plagued by streetwalkers and white customers who come down looking for them. . . . Recently, at Western Avenue and 24th Street, a white man was severely beaten by two teen-age youths who saw him stop his car and try to proposition three young girls on their way to the store. . . . Prostitution, a personal tragedy, is also a big community problem. And Negro leaders and city officials are determined to find a solution.[87]

In 1983-86 authorities cracked down on open drug sales on West Adams Boulevard, for example revoking the business licenses of a motel and a liquor store, which was "virtually an open market for drug sales," according to City Attorney James K. Hahn.[89] In 1986 some of the 850 pay telephones in the West Adams area were removed because they were being used by drug dealers.[90]

By 2011 it was reported that gangs had switched from selling drugs to offering women as prostitutes. A city crackdown along Western Boulevard forced a motel to stop renting rooms by the hour, but the street, as Los Angeles Times columnist Sandy Banks reported, had long been "a hub for prostitution, a money-making spot for locals and a standard stop on the circuit for statewide trafficking rings."[91]

1965-present. Oil drilling and extraction

After hearing a report in December 1965 that there was a "good possibility" of commercial oil production from fields in West Adams, the Los Angeles City Council approved seven oil-extraction districts totaling 388 acres, six of them owned by Richfield Oil Company and the seventh by Standard Oil of California. All were to drill from the same site, a church property at 23rd Street and St. James Place. Boundaries were generally 21st and 22nd streets, Grand Avenue, 29th and 29th streets and Vermont Avenue.[92] Allen Company took over the site in 2009 and increased production; neighbors complained about a foul stench, headaches and nosebleeds. Even federal officials got sick in visiting the site, and the company suspended operations at the request of U.S. Senator Barbara Boxer. It did however, stand ready in October 2015 to resume pumping as soon as the city could adopt new regulations for it to follow.[93]

In April 2004 City Council member Martin Ludlow asked city officials to investigate complaints from neighbors of an oil-pumping operation in the 2100 block of West Adams Boulevard. Residents said the noise from machinery and the smell of oil was "irritating and disruptive." The site was owned by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which received reported $300,000 a year in royalties.[94]

In November 2014 another oil company, Freeport-McMoRan was operating wells at Jefferson Boulevard and Budlong Avenue and was seeking city permission to drill one new well and redrill two old ones. Neighborhood residents protested at a zoning commissioner's hearing, saying there was noise and stench,[95] with some three hundred underground pipelines spreading out from that one location, called the Las Cienegas Field. In January 2014 some three hundred residents protested drilling by the same company at another location, the Murphy drill site at 2126 West Adams Boulevard.[96] In August 2015 neighbors opposed a plan by Freeport to install an enclosed burner to dispose of unused gas that is extracted from the earth.[97]

1992. Rodney King riots

Historic West Adams was not spared from the rioting that enveloped parts of Los Angeles in 1992 after the acquittal of white police officers who had been videotaped beating a black motorist, Rodney King, in the San Fernando Valley. Stores were looted. Flames consumed three apartment buildings on West Adams Boulevard as well as an A.N. Abells Auction building. A supermarket and a Newberry's department store at the corner of Western Avenue and Venice Boulevard were looted and heavily damaged.[98] Two of the black-owned Golden Bird fried-chicken restaurants – the original on West Adams and one in the Midtown Shopping Center – were burned to the ground.[99]

After the riots, there was a question whether the West Adams Heritage Association would go ahead with its annual holiday dinner, but it was held on schedule in December 1992.[100] As a legacy of the disturbances, many people moved out of Historic West Adams. Others, lured by fallen real-estate values, moved in.[56]

1994. Northridge earthquake

Bounded by Adams and Rimpau boulevards, Palm Grove Avenue and Hickory Street, a four-block section of Historic West Adams was severely damaged by the Northridge earthquake of January 17, 1994. It was one of the few places outside the San Fernando Valley that city authorities designated as a "ghost town" in wake of the massive temblor and the only one composed primarily of single-family homes. Eight months after the quake, 53 West Adams buildings were still vacant.[101]

See also

Notes and references

Some of the links may require the use of a library card.

- ↑ John Patterson, "A Resident Expert's Guide to West Adams, Los Angeles's Neighborhood of the Year," January 12, 2016

- ↑ Map, "Los Angeles Central & Western Area," Automobile Club of Southern California, 2002–2013

- 1 2 Doug Smith, "MappingL.A. Project Is Revised in Nearly 100 Ways," Los Angeles Times, June 3, 2009

- ↑ "Mid-City," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "Arlington Heights," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "Pico-Union," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "South L.A.," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "About West Adams," West Adams Heritage Association

- ↑ "Glen Airy Place," Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1911, page V-15

- ↑ "Glen Airy Place," Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1912, page V-13

- ↑ "Glen Airy Place," Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1912, page VI-12

- ↑ "Lighting Petitions Filed," Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1924, page 21

- ↑ "Ground Broken Last Week for Church," Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1924, page E=6

- ↑ "Storm Drain Work Rushed," Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1925, page A-3

- ↑ G.W. Baist, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Plate 36, Los Angeles, California, 1921

- ↑ Mithers, Carol (April 17, 2005). "Vanishing: The history of one house in L.A.". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Oliver, Marilyn Tower (October 1, 1995). "In Touch with the Past: Craftsman-style homes in three neighborhoods recall gracious days of yore. Today they rate among L.A.'s best buys". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Historic West Adams Tour". PreserveLA.com. October 9, 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Diane Wedner, "Taking Over From Titans," Los Angeles Times, September 16, 2007

- ↑ Communications, Emmis (January 1998). Dial Them For Murder. Los Angeles Magazine.

- ↑ "The Marlborough School for Girls," Los Angeles Herald, June 11, 1890, page 3

- ↑ "News Notes," Los Angeles Herald, February 5, 1891, page 8

- ↑ "Burglar Robs Girls' School," Los Angeles Herald, November 3, 1907, page 1

- ↑ "New Marlborough School," Los Angeles Times, "New Marlborough School," Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1916, page II-3

- ↑ Alice Hicks Burr, "St. James Park Enshrines Aura of Oldtime City," Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1942, page d-2

- 1 2 "Dry West Adams," Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1906, page II=5

- ↑ "Hotel to Be Set in Park," Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1913, page V-1

- ↑ "Making Great Boulevard of West Adams Street," Los Angeles Times August 6, 1916, page II-15

- ↑ "She Vanishes From Street," Los Angeles Times, May 13, 1909, page II-1

- ↑ "West Adams Jobless Aided," Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1931, page A=8

- ↑ Emily Green, "Greening: Where the World Is Abloom," Los Angeles Times, April 24, 2003, page F-13

- ↑ "Bauer Tract to Be Platted," Los Angeles Times, July 9, 1905, page V-14

- ↑ "Latest Invasion by Apartments," Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1906, page II-9

- ↑ "Looks Like Fine Home," Los Angeles Times, January 17, 1909, page V-1

- ↑ "Auto Club Will Build New Home," Los Angeles Times, June 26, 1921, page V-1

- ↑ "Ground Broken Last Week for Church," Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1924, page E-6

- ↑ "West Adams Breaks Ground," Los Angeles Sentinel, August 31, 1989, page C-11

- ↑ Scott Harris, "Days Are Numbered for Historic Mansion That Sparked Racial Politics," Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1991

- ↑ Vicki Torres, "Church Group's 1st Project Opens in the Inner City," Los Angeles Times, January 26, 1992, page VC-B-9

- ↑ Bing maps

- ↑ Bob Pool, "Old House Seeks a New Place It Can Call Home," Los Angeles Times, May 27, 2004

- ↑ Eric Sondheimer, "Turmoil in West Adams Prep's Sports Program Raises Questions," Los Angeles Times, November 13, 2012

- ↑ U.S. News and World Report

- ↑ Kevin Thomas, "Film Gives Mansion a Last Fling," Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1971, page G-1

- ↑ Now the Bellevue Recreation Center. "Reservoir Site to Become Park," Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1959, page 32

- ↑ Supreme Court Upholds City Zoning Ordinances," Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1925, page A-1

- ↑ George Lee Miller et al., Appellants v. Board of Public Works of the City of Los Angeles et al., Respondents, L.A. No. 8012, 195 Cal.477; 234 P. 381; 1925 Cal. 386; 38 A.L.R. 1479 (February 27, 1925)

- ↑ Now the site of Cienega Elementary School.

- ↑ "Fire on 'Extras' Flares in Open," Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1926, page A-1

- ↑ "Gadd Loses in Drain Battle," Los Angeles Times February 10, 1972, pages A-1 and A-2

- ↑ Jill Stewart, "'Fair Share' Policy on Poverty Funds Hit: Urban Blight," Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1990, page B-1

- ↑ "2015 Los Angeles's Curbed Cup Neighborhood of the Year Goes to West Adams," CurbedLA, January 13, 2016

- 1 2 Khouri, Andrew (April 30, 2014) "Soaring home prices spur a resurgence near USC " Los Angeles Times

- ↑ "Negro Owners Win Contest on Occupancy," Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1946, page A-1

- ↑ "California: Victory on Sugar Hill," Time, December 17, 1945

- 1 2 Peter Y. Hong, "Legacy of the Riots: 1992-2002, How the Looters Stole a Dream," Los Angeles Times, April 26, 2002, page A-1

- ↑ "Eighty Years Ago, West Adams Boulevard Was a Fashionable Neighborhood. Today, a Group of Pragmatic Young Homeowners Is Restoring Its Glory," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1986, page 30

- ↑ "The 'Battle' of West Adams: White Restorationists Buying Homes in Largely Black L.A. Neighborhodd and Hostility to Them Has Risen," Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1985, page 1

- ↑ West Adams on the Down Low : Curbed LA

- ↑ Edward J. Boyer, "Intruders Spray-Paint Epithets in a Homosexual Couple's Mansion in the West Adams District," Los Angeles Times, June 17, 1994, page 3

- ↑ "One Booth Destroyed," Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1896, page 10

- ↑ "For Charity's Sake: Gipsy Encampment – Brilliant Scene at St. James Park," Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1896, page 7

- ↑ "Officer Slain in Night Fight on Chester Place," Los Angeles Times, January 25, 1916, page B-1

- 1 2 "Perils Hedge Burning Beds of Peat," Los Angeles Times, September 18, 1927, page B-7

- ↑ "Odor From Peat Fire Rouses Ire," Los Angeles Times, July 19, 1927, page A-9

- ↑ "Peace Near in Peat-Bed Fire Strife," Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1927, page A-20

- ↑ "Peat Fire Warrants Out," Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1927, page A-5

- ↑ "Ex-Member Scores City Councilmen," Los Angeles Times, October 26, 1927, page A-15

- ↑ "Peat Fire Battle Nears" Los Angeles Times, October 10, 1927, page a-1

- ↑ "Peat Fund Approved by Mayor," Los Angeles Times, November 9, 1927, page A-5

- ↑ "Peat Defendants Freed," Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1927, page A-1

- ↑ "Anita M. Baldwin to Get Peat-Fire Bill," Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1928, page A-1

- ↑ "Peat Fire Held Sole City Obligation," Los Angeles Times, October 25, 1928, page A-1

- ↑ "Fears for Girl Tots Grow," Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1924, page A-1

- ↑ "Finding of Lost Tots Demanded," Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1924, page A-1

- ↑ "Giant Hunt for Children Fails," Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1924, page A-9

- ↑ "Find Two Lost Girls Buried in California," The New York Times, February 5, 1925

- ↑ "Mother Pleads to Save Stone," Los Angeles Times, January 16, 1927, page 18

- ↑ "Stone Escapes Gallows in Martin Girls Case," Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1927, page 2

- ↑ "Convicted Slayer of Two Children in 1924 Pardoned," Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1941, page 4

- ↑ "Distillery Discovered in Mansion," Los Angeles Times, September 24, 1927, page A-16

- ↑ Lela Ward Oliver, "Tagging of Black Homes More Than a Gang Issue," Los Angeles Sentinel, March 31, 2005, page A-1

- ↑ Sandy Banks, "West Adams Fights Back: Fed-Up Residents Give Police a Powerful Tool to Use Against Street Crime," Los Angeles Times, July 26, 2011, page A-2

- ↑ "Campaign On to 'Clean-up' Western Avenue," Los Angeles Sentinel, May 30, 1967, page A-2

- ↑ "Vice Cleanup Demanded in Some City Districts," Los Angeles Times, October 11, 1960, page 21

- ↑ "Vice Hearing Set for Tonight," Los Angeles Sentinel, October 13, 1960, page A-2

- 1 2 3 Paul Coates, "Vice Casts Its Shadow on West Adams District: White Men on Prowl for Negro Streetwalkers." April 11, 1965, pages B-1 and B-18

- ↑ A.S. (Doc) Young, "Prostitution: It's a Recurring Problem," Los Angeles Sentinel, March 31, 1960, page 8-A

- ↑ "State Revokes License of Adams Blvd. Liquor Store," Los Angeles Sentinel, March 27, 1986, page A-12

- ↑ Don Rosen, "A Call to Action: West Adams Wants Outdoor Pay Phones Removed in War on Drugs," Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1986, page 1

- ↑ Sandy Banks, "West Adams Neighbors Fight for Their Streets," Los Angeles Times, July 26, 2011

- ↑ "West Adams Oil Drilling Districts Set," Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1965, page B-11

- ↑ Emily Alpert Reyes, "City Sets Oil Drilling Rules But Doesn't Enforce Them," Los Angeles Times, October 14, 2015, page A-1

- ↑ Bob Pool, "Los Angeles: City to Look Into Noise, Fumes," Los Angeles Times, April 18, 2004, page B-2

- ↑ Miriam Hernandez, "Public Weighs In on West Adams Oil-Drilling Site," Eyewitness News ABC7

- ↑ Sahra Sulaiman, "West Adams Neighbors Come Together to Oppose the Drillers Next Door," Streetsblog LA, January 14, 2014

- ↑ Emily Alpert Reyes, "Plan to Burn Gas at Oil Drilling Site Resisted," Los Angeles Times, August 17, 2015, page B-3

- ↑ "Days of Devastation in the City," Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1992, page WB-2

- ↑ A.S. (Doc) Young, "Untold Numbers of Black Businesses Destroyed, Thousands of Jobs Lost," Los Angeles Sentinel, May 14, 1992, page A-3

- ↑ Minnie Bernardino, "Good Dinners Make Good Neighbors," Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1992, page H-20

- ↑ Lucille Renwick, "Battered, Nearly Abandoned, a Neighborhood in West Adams Struggles to Piece Itself Together Eight Months After the Earthquake," Los Angeles Times, October 2, 1994, page 14

Additional reading

- Susan Price, "On the Street of Dreams: Eighty Years Ago, West Adams Boulevard Was a Fashionable Neighborhood. Today, a Group of Pragmatic Young Homeowners Is Restoring Its Glory," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1986, page 30

- Ruth Ryon, "New Owners Trace History: Descendants Reuniting in Victorian Residence," Los Angeles Times, January 9, 1983, page J-2

- New photographs of Historic West Adams by Jett Loe

External links

- WAHA—West Adams Heritage Association

- West Adams Heights/Sugar Hill Neighborhood Association

- United Neighborhoods Council

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

.jpg)