History of Animals

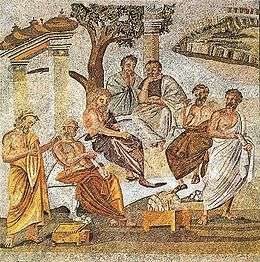

History of Animals (Greek: Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν "Inquiries on Animals"; Latin: Historia Animālium "History of Animals") is a natural history text by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who had studied at Plato's Academy in Athens. It was written in the fourth century BC; Aristotle died in 322 BC.

Generally seen as a pioneering work of zoology, Aristotle frames his text by explaining that he is investigating the what, the existing facts about animals, prior to establishing the why, their causes. The book is thus an attempt to apply philosophy to part of the natural world. His method is to identify differences, both between individuals and between groups. A group is established when it is seen that all members have the same set of distinguishing features; for example the birds all have feathers, wings, and beaks. This relationship between the birds and their features is identified as a universal.

The History of Animals had a powerful influence on zoology for some two thousand years. It continued to be a primary source of knowledge until in the sixteenth century zoologists including Conrad Gessner, all influenced by Aristotle, wrote their own studies of the subject.

Context

Aristotle (384–322 BC) studied at Plato's Academy in Athens, remaining there for some 17 years. Like Plato, he sought universals in his philosophy, but unlike Plato he backed up his views with detailed observation, notably of the natural history of the island of Lesbos and the marine life in the seas around it. This study made him the earliest natural historian whose written work survives. No similarly detailed work on zoology was attempted until the sixteenth century; accordingly Aristotle remained highly influential for some two thousand years. His writings on zoology form about a quarter of his surviving work.[1]

Approach

In the History of Animals, Aristotle sets out to investigate the existing facts (Greek "hoti", what), prior to establishing their causes (Greek "dioti", why).[1][2] The book is thus a defence of his method of investigating zoology. Aristotle investigates four types of differences between animals: differences in particular body parts (Books I to IV); differences in ways of life and types of activity (Books V, VI, VII and IX); and differences in specific characters (Book VIII).[1]

To illustrate the philosophical method, consider one grouping of many kinds of animal, 'birds': all members of this group possess the same distinguishing features—feathers, wings, beaks, and two bony legs. This is an instance of a universal: if something is a bird, it will have feathers and wings; if something has feathers and wings, that also implies it is a bird, so the reasoning here is bidirectional. On the other hand, some animals that have red blood have lungs; other red-blooded animals (such as fish) have gills. Here one can rightly conclude that if something has lungs, it has red blood; but Aristotle is careful not to imply that all red-blooded animals have lungs, so the reasoning here is not bidirectional.[1]

Organisation

Book I The grouping of animals and the parts of the human body.

Book II The different parts of red-blooded animals.

Book III The internal organs, including generative system, veins, sinews, bone etc.

Book IV Animals without blood (non-vertebrates) – cephalopods, crustaceans, etc. In chapter 8, the sense organs of all animals.

Book V Reproduction, spontaneous and sexual of non-vertebrates.

Book VI Reproduction of birds, fish and quadrupeds.

Book VII Reproduction of man.

Book VIII The character and habits of animals, food, migration, health, diseases and the influence of climate.

Book IX The relations of animals to each other, means of procuring food.

A Book X is included in some versions, dealing with the causes of barrenness in women, but is generally regarded as not being by Aristotle. In the preface to his translation, D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson calls it "spurious beyond question".[3]

Translations

The Arabic translation comprises treatises 1–10 of the Kitāb al-Hayawān (The Book of Animals). It was known to the Arab philosopher Al-Kindī (d. 850) and was commented on by Avicenna.

English translations were made by Richard Cresswell in 1862[4] and by the zoologist D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson in 1910.[5]

A French translation was made by J. Barthélemy-Saint Hilaire in 1883.[6] Another translation into French was made by J. Tricot in 1957, following D'Arcy Thompson's interpretation.[7]

A German translation of books I–VIII was made by Anton Karsch, starting in 1866.[8] A translation of all ten books into German was made by Paul Gohlke in 1949.[9]

Influence

The comparative anatomist Richard Owen said in 1837 that "Zoological Science sprang from [Aristotle's] labours, we may almost say, like Minerva from the Head of Jove, in a state of noble and splendid maturity".[10]

Ben Waggoner of the University of California Museum of Paleontology wrote that

Though Aristotle's work in zoology was not without errors, it was the grandest biological synthesis of the time, and remained the ultimate authority for many centuries after his death. His observations on the anatomy of octopus, cuttlefish, crustaceans, and many other marine invertebrates are remarkably accurate, and could only have been made from first-hand experience with dissection. Aristotle described the embryological development of a chick; he distinguished whales and dolphins from fish; he described the chambered stomachs of ruminants and the social organization of bees; he noticed that some sharks give birth to live young — his books on animals are filled with such observations, some of which were not confirmed until many centuries later.[11]

Walter Pagel comments that Aristotle "perceptibly influenced" the founders of modern zoology, the Swiss Conrad Gessner with his Historiae animalium, the Italian Ulisse Aldrovandi, the French Guillaume Rondelet and the Dutch Volcher Coiter, while his methods of looking at time series and making use of comparative anatomy assisted the Englishman William Harvey in his work on embryology.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Lennox, James (27 July 2011). "Aristotle's Biology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ History of Animals, I, 6.

- ↑ Thompson, 1910, page iv

- ↑ Cresswell, Richard. A History of Animals. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1862.

- ↑ Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth. A History of Animals. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910.

- ↑ Barthélemy-Saint Hilaire. J. Histoire des Animaux D'Aristote (3 volumes). Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1883.

- ↑ Tricot, J. Histoire des Animaux. Paris, 1957.

- ↑ Karsch, Anton. Natur-geschichte der Thiere. Zehn Bücher. Stuttgart. Vol 1, 1866. Vols 2 and 3, n.d.

- ↑ Gohlke, Paul. Tierkunde, being section VIII.1 of Die Lehrschriften. Paderborn, 1949. 2nd Edition 1957.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (1992). Sloan, Phillip Reid, ed. The Hunterian Lectures in Comparative Anatomy (May and June 1837). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 91.

- ↑ Waggoner, Ben (9 June 1996). "Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.)". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Walter Pagel (1967). William Harvey's Biological Ideas: Selected Aspects and Historical Background. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. p. 335. ISBN 978-3-8055-0962-6.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- English translation by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910. Adelaide library – Archive.org

- English translation by Richard Cresswell. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1862.

- Complete Works of Aristotle, Volume 1: Revised Oxford Translation. Edited by Jonathan Barnes. Princeton University Press, 1984.