Hispano-Celtic languages

Hispano-Celtic is a hypernym to include all the varieties of Celtic spoken in the Iberian Peninsula before the arrival of the Romans (in c. 218 BC, during the Second Punic War):[3][4]

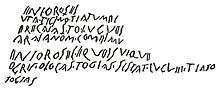

- a northern-eastern, inland language attested at a relatively late date in the extensive corpus of Celtiberian.[2] This variety, which Jordán Cólera[3] proposed to name northeastern Hispano-Celtic, has long been synonymous with the term Hispano-Celtic and is universally accepted as a Celtic language.

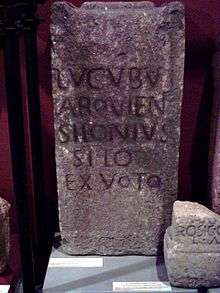

- a language in the north west corner of the peninsula, with a northern and western boundary marked by the Atlantic Ocean, a southern boundary along the river Douro, and an eastern boundary marked by Oviedo, which Jordán Cólera has proposed to call northwestern Hispano-Celtic, where there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions containing isolated words and sentences that are clearly Celtic. [5][3]

Western Hispano-Celtic is a term that has been proposed for a putative spectrum of Celtic and para-Celtic dialects, west of an imaginary line running north-south linking Oviedo and Mérida.[3][6] According to Koch, the Western Celtic varieties of the Iberian Peninsula share with Celtiberian a sufficient core of distinctive features to justify Hispano-Celtic as a term for a linguistic sub-family as opposed to a purely geographical classification.[2]:292 In Naturalis Historia 3.13 (written 77–79 CE), Pliny the Elder states that the Celtici of Baetica (now western Andalusia) descended from the Celtiberians of Lusitania, since they shared common religions, languages, and names for their fortified settlements.[7]

As part of the effort to prove the existence of a western Iberian Hispano-Celtic dialect continuum, there have been attempts to differentiate the Vettonian dialect from the neighboring Lusitanian language using the personal names of the Vettones to describe the following sound changes (PIE to Proto-Celtic):[6]:351

- *ō > ā occurs in Enimarus.

- *ō > ū in final syllables is indicated by the suffix of, e. g., Abrunus, Caurunius.

- *ē > ī is attested in the genitive singular Riuei.

- *n̥ > an appears in Argantonius.

- *m̥ > am in names with Amb-.

- *gʷ > b is attested in names such as Bouius, derived from *gʷow- 'cow'.

- *kʷ in PIE *perkʷ-u- 'oak' appears in a lenited form in the name Erguena.

- *p > ɸ > 0 is attested in:

- *perkʷ-u- > ergʷ- in Erguena (see above).

- *plab- > lab- in Laboina.

- *uper- > ur- in Uralus and Urocius.

- However, *p is preserved in Cupiena, a Vettonian name not attested in Lusitania; also in names like Pinara, while *-pl- probably developed into -bl- in names like Ableca.[2][8]

See also

- Celtiberian language

- Gallaecian language

- Continental Celtic languages

- List of Galician words of Celtic origin

- List of Spanish words of Celtic origin

- Tartessian language

- Celtic languages

- Paleohispanic languages

References

- ↑ Meid, W. Celtiberian Inscriptions (1994). Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapítvány.

- 1 2 3 4 Koch, John T. (2010). "Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Celtic Studies Publications. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. Reissued in 2012 in softcover as ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Jordán Cólera, Carlos (March 16, 2007). "The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula:Celtiberian" (PDF). e-Keltoi 6: 749–750. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2005). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 481. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ↑ Prósper, Blanca María (2002). Lenguas y religiones prerromanas del occidente de la península ibérica. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. pp. 422–427. ISBN 84-7800-818-7.

- 1 2 Wodtko, Dagmar S. (2010). "Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Celtic Studies Publications. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.:360–361 Reissued in 2012 in softcover as ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. "3.13". Naturalis Historia.

Celticos a Celtiberis ex Lusitania advenisse manifestum est sacris, lingua, oppidorum vocabulis, quae cognominibus in Baetica distinguntur

. Written 77–79 CE. Quoted in Koch (2010), pp. 292–293. The text is also found in online sources: , . - ↑ Lujan, E. (2007). Lambert, P.-Y.; Pinault, G.-J., eds. "L'onomastique des Vettons: analyse linguistique". Gaulois et celtique continental (in French) (Geneva: Librairie Droz.): 245–275.